This Favoured Land

Edward King-Tenison and Lady Louisa in Spain, 1850–1853

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

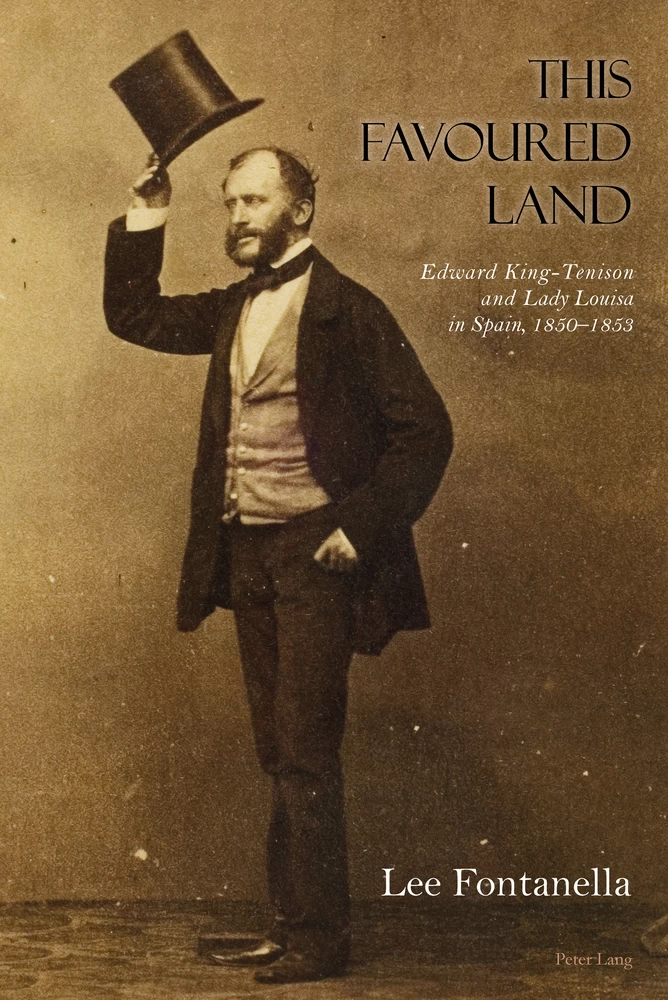

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Foreword and acknowledgments

- Chapter 1: How I met the Tenisons, who they were, and why they so interested me

- Chapter 2: The sociability and civic-mindedness of the Tenisons

- Chapter 3: The Spanish sojourn: Profound substrata that serve to define both civic and artistic differences between the Tenisons and Spaniards

- Chapter 4: Sketching and photographing

- Chapter 5: Tracing the Spanish sojourn: Calendar, general route and excursions

- Index

Relatively little has been written about Edward King-Tenison and Lady Louisa Tenison, although they were definitive in their respective cultural accomplishments: he as pioneer photographer; she as chronicler of travels and sketch artist and colorist. Nor was either lacking in other achievements: he in the socio-political arena; she in that of international relations, particularly in the field of art. Their joint accomplishments were so unusually great that the task of delineating them has proved daunting; and especially so, when their achievements are taken jointly and complementarily. It is indeed hard to imagine, without repeated, meticulous review of their joint activity, just how such an adventurous duo may have teamed up to produce the vast quantity of singular work that they did produce; work so ultimately meaningful that it could serve as a jumping-off point for gaining a perspective on the subsequent cultural achievements of others who worked along similar lines. Nonetheless, that was the case: a seemingly magical coming-together of two artistic and technical power-houses who produced an undeniably influential body of work which, if it did not always aggrandize Spain, rendered to Spain a significance that was unforgettable in a more general scheme of cultural noteworthiness.

I have grappled with this vast perspective for over a decade, while continuing to cultivate the panoply of related scholarly interests and public activities that have characterized my professional life for the past nearly half-century. While I have availed myself of what little has been ventured concerning the Tenisons, I have found that what has been said has not always turned out to be correct. Some were admirable attempts at hitting the mark in a field where surprisingly little has been said, but not always constructive information for the scholar who chooses to push ahead and speculate further. It is a field which at first blush appears deceptively small, circumscribed, and almost restricted, but which in the end has broad implications in the cultures that the Tenisons fearlessly trod. Most significantly, what I have found entirely lacking in any of the few remarks about the ← ix | x → Tenisons are insights into the many ways in which E. K. Tenison and Lady Louisa fit into a much larger cultural context.

E. K. Tenison, as he signed himself (also “E. K. T.”), was one of the earliest and greatest photographers of Spain and arguably the first who attempted to type the Spaniard – most particularly, the Andalusian gypsy – photographically and, as it happened, in a starkly prosaic manner, in contrast to the foreign painters who rendered their florid Romantic image of those human types. This was E. K. Tenison’s contribution to the visual store about Spain, which was being gathered for all manner of reasons, some more morally justifiable than others, perhaps. For most historians of the visual image, it was E. K. Tenison’s “topographic” photographs (photographs of Spain’s monuments and outdoor perspectives) that have been the focus of interest. But the images of human types, which lay entirely undiscovered until 2004 – a tale not quite as worthy of its own narration as that of the Tenisons’ sojourn itself, but certainly crucial in the present study – will gain here a critical and cultural importance as great as that which his “topographic” views of Spain have heretofore enjoyed.

In the present book, the work of Lady Louisa takes no back-seat to the work of her spouse. In fact, her contribution to the entire Spanish venture, even beyond it, was undeniably immense, arguably greater than that of E. K. Tenison, although it has not been viewed that way, probably because the Tenisons returned to the limelight through the interests of photohistorians. This is a pity, even seen from an artistic viewpoint. Lady Louisa must have been the greater impulse behind the Spanish sojourn, and she was a manual artist in her own right and a remarkable writer who maintained a diligent chronicle of their journey, replete not only with detailed observations of what elements constituted that journey, but also with critical observations about contemporaneous factors, about history, and about all sorts of socio-political issues. In the course of these remarks, naturally sometimes slanted by her particular cultural stance, Lady Louisa showed a perspicacity that shocks us today for its far-seeing nature based on truly critical acumen. To judge by her chronicle, Lady Louisa was extraordinarily bright, artistically talented, and a powerful mover and organizer, her spouse’s own social and professional positions notwithstanding. ← x | xi →

In addition to Louisa Tenison’s lengthy travel account, fundamental sources for this study have been the following: the album (or scrapbook) that rested for decades in the hands of Mr Carr, and which now forms part of Irish patrimony. It is in the National Library. Over the past decade, Ireland’s center for photographic resources and its National Library – separate entities, but both located in central Dublin – have shared generously both the “scrapbook” and other, more formal Tenison family albums, and most of these have come into play in varying degree in this study. However, as I imply in Chapter 1, the Carr album has been crucial to my research and speculations about the Tenisons’ enterprise in Spain. Indeed, without it, the present book’s course and conclusions would have been impossible. That said, I would underscore that the more formal albums are certainly more basic to a biographical unfolding of the Tenisons and their society, both familiar and purely social, and I have made what references to this that I deemed necessary for a comprehension of the Spanish venture. Other writers less concerned with Spain and E. K. Tenison’s photographic achievement, or with Lady Louisa’s multiple artistic undertakings, and rather more concerned with biography, would underplay the scrapbook and give more weight to other Tenison-related albums that Ireland holds. There is nothing to compare with the French National Library’s Tenison album, if one is focusing on E. K. Tenison’s topographic views of Spain. It is a splendid array of prime work, which establishes his indisputable place as one of the great early photographers of Spain. The international and broad artistic ramifications of my study would have been impossible – at best unlikely – without the cooperation of various aspects of Swedish patrimony. This is patently evident in Chapter 4. Stockholm’s National Library, Archives, and Art Museum, and Göteborg’s Art Museum and holdings, have for years been made available to me, all of which comes to light in reference to Louisa Tenison’s cooperative efforts with Swedish artist Egron Lundgren.

Lundgren is just one example – probably the most notable one – of how this study is expansive. I mentioned that its parameters could appear deceptively small at first glance. In reality, it is the opposite in its multifacetedness: an exemplar of travel literature; a stunning moment in international photohistory; a fearlessly incisive commentary on nineteenth-century Spain, variously manifested; an exemplar of inter-artistic cooperation and ← xi | xii → complex, innovative mediatory transmission of information, through the written word and several different kinds of visual imagery, not just photography. Less apparent is the moral message involved in the experimental photography in which E. K. Tenison engaged from the start of the sojourn, even continuing into his period of more technically elegant topographic photography of Spain.

Also unapparent may be the fact of the nature of the research that underlay this study: amply international (Ireland, Sweden, France, Spain) and over the course of many trips to these countries. Similarly, the text that follows is evidence of necessary multidisciplinary considerations, not just in literary and several visual arts, but also social sciences. Both factors speak of research that is broadly geographic and of the bringing to bear of several disciplines. So, what may appear to be “micro-history” can be expansive at the same time.

The official institutions that I have mentioned have been incorporated in the foregoing paragraphs with grateful appreciation. The immensely helpful individuals at those institutions deserve, each of them, a bonus for their patience and attention. Other individuals have helped to further my study of the Tenisons: Andrew Wilson, himself a contributor to the Irish patrimony that concerned me; Tom Bean, with his eagle-eye for miscellany; also in the UK, colleagues Hilary Macartney and Andrew Ginger; and in Spain my colleagues Ricardo González, Isabel Ortega, Gerardo Kurtz, María Teresa García Ballesteros and Juan Antonio Fernández Rivero. I will likely regret having missed a dozen other worthy individuals. That said, I would thank Juanjo Sánchez García for pushing and Ángel Gómez Montoro and Jaime García del Barrio for hearing me out. ← xii | 1 →

Details

- Pages

- XII, 178

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781787078772

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781787078789

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781787078796

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783034322089

- DOI

- 10.3726/b13302

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2017 (November)

- Keywords

- Travel in Spain Photographic history Art

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, New York, Wien, 2017. XII, 178 pp., 31 b/w ill., 14 fig.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG