From Orientalism to Cultural Capital

The Myth of Russia in British Literature of the 1920s

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Preface (Professor Philip Ross Bullock)

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: The East Wind of Russianness

- Chapter 2: John Galsworthy: Is It Possible to ‘De-Anglicise the Englishman’?

- Chapter 3: H. G. Wells: Interpreting the ‘Writing on the Eastern Wall of Europe’

- Chapter 4: J. M. Barrie and The Truth about the Russian Dancers

- Chapter 5: D. H. Lawrence: ‘Russia Will Certainly Inherit the Future’

- Chapter 6: ‘Lappin and Lapinova’: Woolf’s Beleaguered Russian Monarchs

- Chapter 7: ‘Not a Story of Detection, of Crime and Punishment, but of Sin and Expiation’: T. S. Eliot’s Debt to Russia, Dostoevsky and Turgenev

- Bibliography

- Index

How does the marginal become mainstream? And how does the recherché become démodé? These questions run through the chapters of this book like a red thread, structuring its arguments and provoking the reader to examine some familiar names and some familiar works, as well as a host of more unusual and overlooked material. And they are pertinent and productive questions, too, because they point to the dizzying rapidity with which Russian culture became known (if not always understood) in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Britain, as well as the way in which that culture soon became reduced to cliché and myth. Said and Bourdieu structure the argument, as announced in the book’s title, but their work is never read reductively. Said’s ‘Orientalism’ is the explicit productive of ‘Orientalists’, writers and critics keen to paint a picture of Russia as barbaric and ‘other’. And Bourdieu’s ‘literary field’ (a concept that has proved as productive as that of ‘cultural capital’) is one that is populated by agents and actors who are conscious of their choices, if not always of their expertise (or lack thereof). In many ways, however, the ideas presented here are already implicit in Russian culture itself, which has long been aware of both its belatedness and its precocity, and how these seemingly contradictory features structure its relationship with the rest of the world. In his famous Lettres philosophiques, written (in French, no less) in the late 1820s and early 1830s, Pyotr Chaadaev announced both Russia’s lack of history and its negligible contribution to world culture: ‘Alone in the world, we have given it nothing, we have taught it nothing; we have added not a single idea to the multitude of man’s ideas; we have contributed nothing to the progress of the human mind and we have disfigured everything we have gained from this process.’ Alexander Herzen described Chaadaev’s writings as ‘a shot that rang out in the dark night’, and indeed the mid-century saw a remarkable oscillation between those who defended Russia’s place in Europe, and those who sought to situate its riches elsewhere. The idea that self-definition was the product of a dialogue was, moreover, implicit ← ix | x → in Herzen’s writings, and in words that might have served – in inverted form – as an alternative subtitle to this volume, he claimed that ‘we need Europe as an ideal, as a reproach, as a virtuous example; if Europe were not these things, then we should have to invent it.’ Both Chaadaev and Herzen might have been surprised to see their diagnoses wholly inverted by the fin de siècle, when it was Russia that found itself playing the role of the West’s own subconscious, unruly and disruptive, yet also libidinal and highly creative. The interplay between stasis and regeneration, ossification and renewal is also central to the work of the Russian formalists, whose revolutionary ideas on literary theory and history were coterminous with Freud’s archaeology of the mind. The language and metaphors employed by the formalists bespeak rupture and revolution. Not for them a direct and unbroken lineage of literary development, but a series of ‘knight’s moves’, of quasi-Oedipal rejections of paternal influence, and the search for alternative genealogies, whether in the form of marginal genres, unfamiliar cultures, or inventive new devices that disrupt the hold of the past over the values of the present. Yet as the formalists were only too aware, one generation’s radical innovation becomes the next generation’s ossified platitude, and their model of artistic evolution is one that can be applied to patterns of transcultural reception too. The seeming ubiquity of Russian culture in early twentieth-century Britain was an enterprise (and the word is advisedly chosen for its economic associations) that carried with it a highly durable form of canonisation that has proved hard to overcome. Between October 2016 and February 2017, the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris staged an exhibition – Icons of Modern Art – which reunited the collection of the merchant and patron, Sergei Shchukin. The exhibition attests, of course, to Shchukin’s farsightedness (as well as his financial ease), but equally, it shows how the once radical inventive has become part of the cultural heritage of the homme moyen culturel. Or consider the incorporation of the scores of Stravinsky, the choreographies of Balanchine, Fokine and Nijinsky, and the designs of Bakst and Benois into the repertoire of the Mariinsky Theatre in St Petersburg, at once effacing both the Soviet avant garde and the legacy of socialist realism, and projecting a continuous tradition that runs from Marius Petipa to the present day, as well as a Russian version of Diaghilev’s carefully marketed global brand. So how ← x | xi → are we to regain a sense of the dynamism that first brought Russian culture to Britain, and create a modern version of the processes described by Olga Soboleva and Angus Wrenn? It may be that Russian culture has an answer. Writing in the wake of the October Revolution, and anxious that the orthodoxy of one age would simply be replaced by conventions of a new one, the Soviet writer and essayist Evgeny Zamyatin proposed a model of permanent and dialectical revolution in which heresy was the guarantee of artistic originality: ‘Today is doomed to die, because yesterday has died and because tomorrow shall be born. Such is the cruel and wise law. Cruel, because it dooms to eternal dissatisfaction those who today already see the distant heights of tomorrow; wise, because only eternal dissatisfaction is the guarantee of unending movement forward, of unending creativity.’ We may read From Orientalism to Cultural Capital: The Myth of Russia in British Literature of the 1920s as an analytical account of a historical phenomenon, yet the dynamic model of literary reception and cultural appropriation that it proposes is one that remains acutely contemporary.

Professor Philip Ross Bullock ← xi | xii →

We are grateful to a large number of colleagues and friends with whom we have had the chance to discuss informally the themes of this book. First and foremost we are immensely grateful to Professor Philip Ross Bullock of Wadham College, Oxford for the benefit of his expertise in this field over many years and especially for kindly agreeing to write the preface to this volume. Professor Rebecca Beasley of Queen’s College, Oxford and Dr Matthew Taunton (University of East Anglia), very much the driving forces behind the Russia Research Network which has been meeting regularly in London, deserve special thanks for providing encouragement and direction throughout the past two years. Professor Patrick Parrinder, doyen of Wells scholars, very kindly spoke at LSE at our invitation, and gave invaluable help in relating the period of Wells’ life covered in this book to the writer’s career overall. We would like to thank Professor Leonee Ormond for her expertise and encouragement in the fields of Barrie and Galsworthy. Dr Alexandra Smith provided very helpful suggestions on D. H. Lawrence. We also thank: Victoria and Albert Museum Collections; Punch archives, Tate Britain and Press Association collection for assistance with images. Christabel Scaife, our editor at Peter Lang, has been patient and helpful in equal measure in seeing the project through to completion. ← xiii | xiv →

Part I: ‘They, if anything, can redeem our civilisation’1

Knowledge of Russian culture in Britain grew slowly in the nineteenth century, then rapidly in the first decades of the twentieth; this period has, therefore, always been a popular topic of research, conducted largely from a chronological and historical perspective and with regard to its most prominent practitioners. So far little (if any) attention has been paid to the analysis of the deeper structural changes in the reception of Russian culture in Britain brought forth by this wave of Russophilia in the pre-World War I years. Still less effort has been made to reflect upon whether this quantitative growth of interest in and exposure to Russian literature and art facilitated a qualitative shift in the framework of perception, affecting the mode of thinking of the contemporary British cultural elite, as well as the emerging notion of modernist art.

This book moves into that underexplored territory of research, suggesting an interdisciplinary approach to the critical appraisal of the reception of Russia in Britain by examining it through the structural framework of modern socio-political theories of Edward Said and Pierre Bourdieu. The idea of Russia or the Russian myth projected by the British constitutes the main focus of our examination. It will be argued that all the way through to the turn of the twentieth century, the representation of Russia in Britain largely falls within the framework of Orientalism – the concept developed by Edward Said in his eponymous work of 1978, in which he exposes the depiction of non-Western cultures as politically charged fabrications of the ← 1 | 2 → European imagination, characterised by an essentially Eurocentric, imperialistic, or civilisatory (in the case of Russia) approach. Following Said’s thesis on the significance of literary scholarship in the formation of the Orientalistic viewpoint, we shall look more closely at the post-1910 years with the objective of establishing whether the unprecedented burgeoning of translations from Russian literature in these decades, as well as the exceptional interest in this subject among the British cultural elite, had a crucial impact on and led to a radical change in the configuration of the paradigm of Russian reception. One of the potential effects of this change could be the major shift in the signifying function of the icon: from Russia as the Orientalistic epitome of ‘barbaric splendour’ towards an emblem deployed to connote British intellectual prestige, a valuable artistic commodity translated into the foreign context, or a fashionable contribution to cultural capital, understood in Pierre Bourdieu’s sense of the term.2

Some attempt should be made to specify our approach to interpreting this signifying function of the icon, which effectively sheds more light on the way in which the notion of the Russian myth is employed for the purposes of our examination. This approach is rooted in imagology, or representation studies, concerning structural analysis of discursive articulation of national stereotyping – the form of ‘literary sociology’ in the domain of image making.3 Recent advances in this area are focused on the so-called constructivist perspective, considering any image of national character as culturally constructed within the framework of the given socio-historical context. This ties in well with modern social studies of national identity that have moved away from the ‘realness’ of national character as explanatory model, and towards an increasingly pluralistic and culturally mediated projection – a state of mind rather than a deterministic expression ← 2 | 3 → of the given.4 The latter includes self-image, as well as the image of the other, which suggests yet another inference to be reviewed. In the light of this constructivist perspective, the representation of ‘the other’ should be effectively treated as a particular type of ‘intertext’ – a dynamic product of cultural interference between the ‘auto’ and ‘hetero’ image, shaped by the proclivities of a specific historical context. Considering this, as well as the fact that the impact of the context can never be discarded, the very notion of the discursive image turns out to be intrinsically linked to the semantics of a myth (see Oxford Dictionary’s definition of myth as a ‘widely held but false belief or idea’5) – hence, the use of this term adopted in the course of our discussion, which essentially concerns the projection of the myth of Russia constructed by the British.

This work builds on a rich field of previous (albeit in some cases now dated) research which was effective in highlighting a historiographic approach to Anglo-Russian cultural interaction; the reception of canonical Russian authors in Britain; and the distinctive body of relatively recent scholarship which has expanded the study of literary influence on specific modernist authors.6 It also draws on two newly published interdisciplinary ← 3 | 4 → volumes, A People Passing Rude: British Responses to Russian Culture, edited by Anthony Cross (Open Book Publishers, 2012) and Russia in Britain, 1880–1940: From Melodrama to Modernism, edited by Rebecca Beasley and Philip Ross Bullock (Oxford University Press, 2013), which shifted attention to the contribution of institutions (libraries, publishing houses, theatre) in the promoting and disseminating of Russian literature and art.

This book aims at taking the discussion a step further. Given that the process of cultural representation is determined not by empirical reality (how people ‘really are’), but rather by the way in which the discourse regarding it is constructed – on the basis of vraisemblance rather than vérité, to evoke the neo-Aristotelian juxtaposition, then the ease with which the audience can reciprocate the purport of the projected image should be called into play. In other words, the audience’s acceptance of representation as valid plays a cardinal role in the process of image formation; and in this sense, the reputation of the so-called promoters of the image must not be overlooked. This aspect constitutes one of the key points of our study, which focuses attention on those representatives of the British cultural elite whose talent, though not explicitly and consistently devoted to the complex task of doctrinal formulation, nonetheless gained a significant mastery over the minds of their readers, and attained such a degree of public recognition as to turn institutional practices into effective mediators of their personal aesthetics, their cultural theories and artistic points of view.

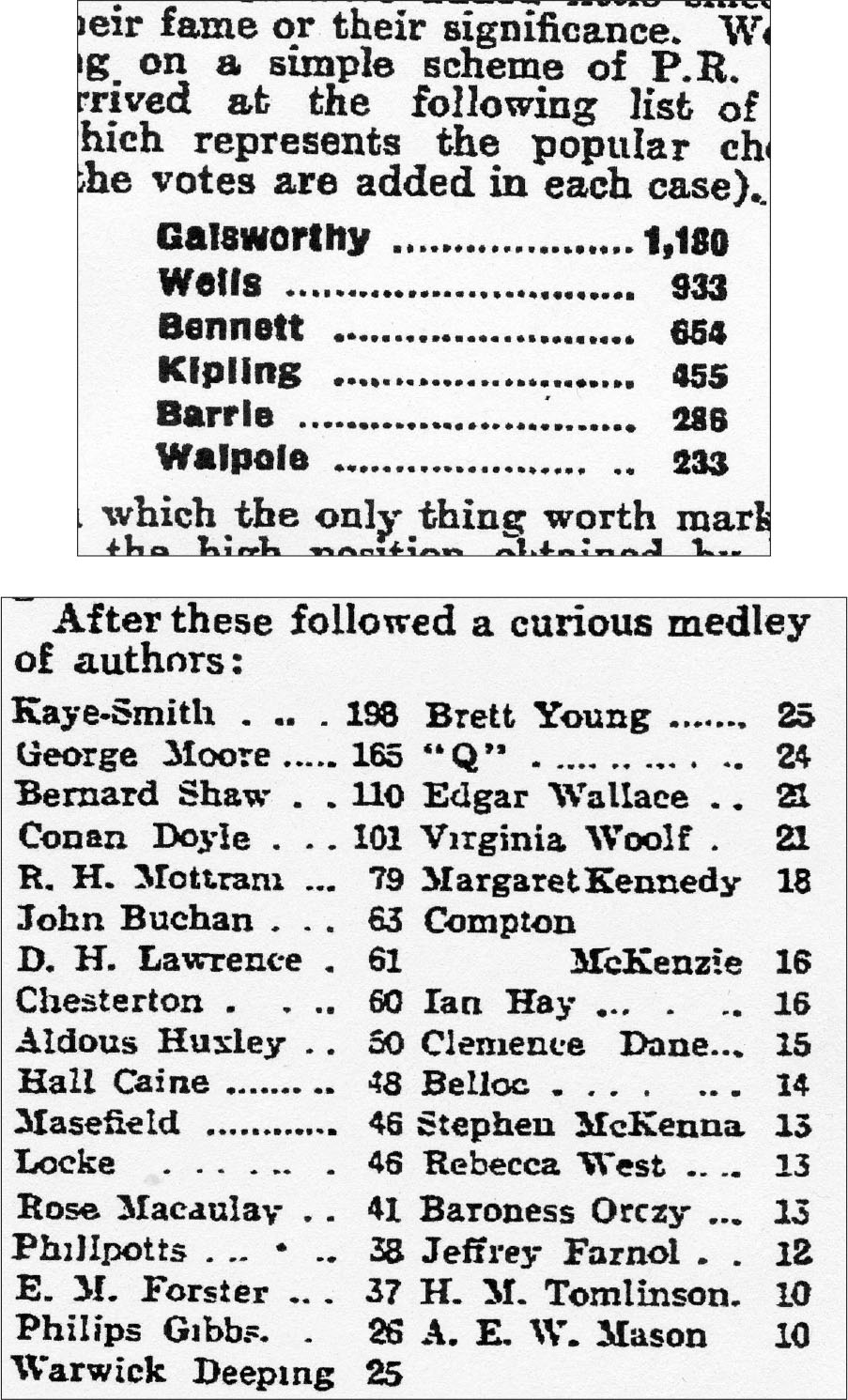

The reputational currents of the 1920s – the leanings and opinions of contemporary readers were central for the rationale of our literary selection. In 1929, the readers of the Manchester Guardian were asked to opine on the ‘Novelists Who May Be Read in A. D. 2029’ (see Figure 1).7 Coming out on top in this century hence popularity contest was John Galsworthy, who defeated H. G. Wells (the runner up), Arnold Bennett and Rudyard ← 4 | 5 → Kipling by a large margin. J. M. Barrie was in fifth position, followed by a curious for the modern eye medley of authors, which included G. B. Shaw (in eighth place), D. H. Lawrence (twelfth) and Virginia Woolf just about managing to get in ‘the first thirty’.

Figure 1. ‘Novelists Who May Be Read in A. D. 2029’, Manchester Guardian, 3 April 1929.

History does not seem to have been on the side of many of these writers, and certain nominations may now be largely regarded as a sheer whim of ← 5 | 6 → literary fashion. This opinion poll, however, did give us a clearer idea for comprising a quintessential (though by no means comprehensive) list of trend-makers in Russian reception. Bearing in mind the evolution of the canon, as well as the authors’ impact on the modern cultural perspective, we tried to highlight the individuals who were instrumental for the issues of institutional transmission of Russian culture, who, having secured their position as major socio-cultural opinion-makers, became pivotal for configuring a particular type of the Russian image, shifting attitudes and paving new ways towards canon formation.

The selection includes John Galsworthy and H. G. Wells – two consecutive presidents of the British P. E. N. Club, the oldest human rights and literary organisation, known for its active agitation for freedom of expression; J. M. Barrie, a leading dramatist at the time, whose contribution to the configuration of the institution of the contemporary British theatre of the early twentieth century is difficult to overestimate (today known exclusively for Peter Pan, but at the time equally famous for plays addressing class – The Admirable Crichton, or gender – The Twelve-Pound Look); D. H. Lawrence, Virginia Woolf (one of the key-members of the Bloomsbury group) and T. S. Eliot (in this period editor of The Criterion) – pioneers of British modernism, who, being united by an abiding belief in the enlightening mission of arts and culture, exerted a seminal influence on literature and aesthetics, as well as on modern attitudes towards pacifism, sexuality and women’s rights. This, of course, is not to say that these writers have ever had a direct impact on or brought about social and political transformation; but it was not uncommon for their contemporaries to see them as the consciousness and spirit of the age: ‘The England of today is in part a Shaw-made and a Wells-made democracy’, as Lady Rhondda put it in 1930.8

Further to the point, the use of the term cultural capital in the title is of considerable significance for the objectives and outcomes of our examination. We aspire to evoke explicitly Pierre Bourdieu’s concept, as it provides a crucial mode of understanding not only the general mechanisms of cultural ← 6 | 7 → reception, but also the differential, and in certain respects modernising, function of the Russian paradigm in the cultural space of early twentieth-century Britain. When analysing the configuration of this paradigm within the framework of the British cultural context, we try to go deeper than the simple binaries of the literary and artistic impact, and focus on the conceptual avenues through which the idea of ‘the exotic other’ was appropriated and internalised in the artistic world of the British authors. The intention is to go into such areas of fictional and poetic creation that may generate other configurations of and perspectives on the notion of ‘the real’, and to expand the boundaries of one’s own familiar self. By taking such a multi-faceted analytical approach to the study of Russian reception in Britain, the book aims not only at placing it in line with the current state of pan-European debate on early twentieth-century culture, but also at casting new light on the British perceptions of modernism, as a transcultural artistic movement, and the ways in which the literary interaction with the myth of Russia shaped and deepened these cultural views.

Part II: ‘Prose and verse have been regulated by the same caprice that cuts our coats and cocks our hats’9

Details

- Pages

- XIV, 338

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781787073944

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781787073951

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781787073968

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9783034322034

- DOI

- 10.3726/b11211

- Open Access

- CC-BY-NC-ND

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2017 (April)

- Keywords

- British literature Russophilia Modernism Anglo-Russian connections

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, New York, Wien, 2017. XIV, 338 pp., 8 b/w ill., 2 fig.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG