Locus Fratrum – Architecture of Observant Franciscan Monasteries in Bohemia, Moravia, Silesia and Upper Lusatia in the Late Middle Ages

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- I. Introduction

- II. Observant Franciscans in the Bohemian Lands in the Late Middle Ages

- III. Monastic regulations in relation to arts and architecture

- IV. Foundation and general principles of the construction of convents

- V. Architecture of Observant Franciscan monasteries?

- VI. Conclusion

- VII. Catalogue of Observant Franciscan monasteries

- Bechyně, monastery with the church of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary

- Brno, monastery with the church of St Bernardino of Siena

- Bytom, monastery with the church of St Nicholas

- Cieszyn, monastery with the church of the Holy Trinity

- Głogów, monastery with the church of SS Peter and Paul and St Bernardino

- Głubczyce, monastery with the church of St Giles and St Bernardino

- Horažďovice, monastery with the church of Holy Angels

- Jawor, monastery with the church of the Virgin Mary and St Andrew

- Jemnice, monastery with the church of St Vitus

- Jindřichův Hradec, monastery with the church of St Catherine

- Kadaň, monastery with the church of the Fourteen Holy Helpers

- Kamenz, monastery with the church of St Anne

- Karłowice, hermitage and the monastery of the Virgin Mary in the Desert

- Kłodzko, monastery with the church of SS George and Adalbert

- Koźle, monastery with the church of the Virgin Mary, St Francis and St Barbara

- Krupka, monastery with the church of All Saints

- Legnica, monastery with the church of the Holy Trinity, the Virgin Mary and St Hedwig

- Nysa, monastery with the church of the Holy Cross (14), monastery with the church of Mary Magdalene (15)

- Olomouc, monastery with the church of the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin Mary and St Bernardino

- Opava, monastery with the church of St Barbara

- Opole, monastery with the church of St Barbara (14), monastery with the church of the Holy Trinity and the Virgin Mary (15)

- Plzeň, monastery with the church of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary

- Prague, monastery with the church of St Ambrose

- Racibórz, monastery with the church of Saints Wenceslas and Hedwig

- Tachov, monastery with the church of SS Mary Magdalene and Elizabeth

- Uherské Hradiště, monastery with the church of The Annunciation to the Virgin Mary

- Wrocław, monastery with the church of St Bernardino of Siena

- Znojmo, monastery with the church of St Francis

- VIII. List of sources and literature

- IX. List of abbreviations

- X. List of figures

Zuzana Křenková

Locus Fratrum –

Architecture of Observant

Franciscan Monasteries in

Bohemia, Moravia, Silesia

and Upper Lusatia

in the Late Middle Ages

![]()

Bibliographic Information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek

The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data is available online at http://dnb.d-nb.de.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress.

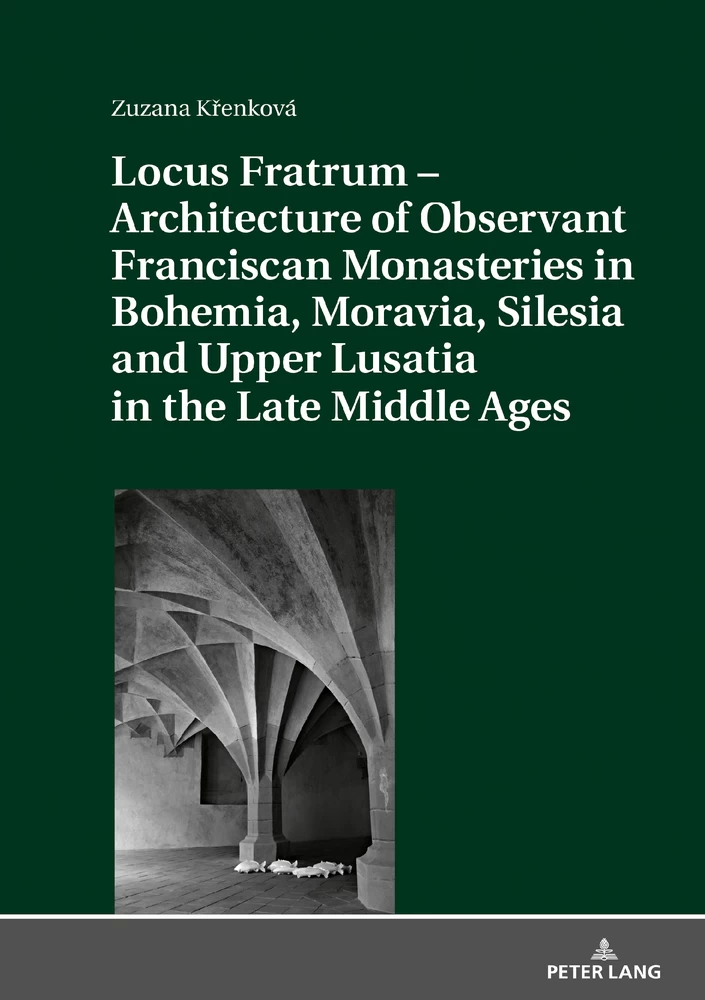

Cover Image: Space on the third storey of the north wing, monastery in Kadaň, view from the east, 2014. © Zuzana Křenková.

The publication has been financially supported by the University of Chemistry and Technology Prague. Translation: Milan Rydvan

![]()

ISBN 978-3-631-77408-3 (Print)

E-ISBN 978-3-631-77501-1 (E-PDF)

E-ISBN 978-3-631-77502-8 (EPUB)

E-ISBN 978-3-631-77503-5 (MOBI)

DOI 10.3726/b14935

© Peter Lang GmbH

Internationaler Verlag der Wissenschaften

Berlin 2018

All rights reserved.

Peter Lang – Berlin · Bern · Bruxelles · New York · Oxford · Warszawa · Wien

All parts of this publication are protected by copyright. Any utilisation outside the strict limits of the copyright law, without the permission of the publisher, is forbidden and liable to prosecution. This applies in particular to reproductions, translations, microfilming, and storage and processing in electronic retrieval systems.

This publication has been peer reviewed.

About the book

The book Locus Fratrum is the first attempt at a systematic analysis of the architecture and building practice of the last major medieval monastic order. The core of the book lies in chapters monitoring the history and building development of the individual monasteries in the territory of the Bohemian monastic province. The catalogue part is preceded by chapters summarizing the historical context of the Observant Franciscans’ activities in the second half of the fifteenth and the first half of the sixteenth centuries, during which the Observants experienced both rise and fall. The history of the order is followed by an exposition on the rules governing the foundation of convents, the monastic rules limiting artwork and above all the character of the order’s architecture.

This eBook can be cited

This edition of the eBook can be cited. To enable this we have marked the start and end of a page. In cases where a word straddles a page break, the marker is placed inside the word at exactly the same position as in the physical book. This means that occasionally a word might be bifurcated by this marker.

Contents

II. Observant Franciscans in the Bohemian Lands in the Late Middle Ages

III. Monastic regulations in relation to arts and architecture

IV. Foundation and general principles of the construction of convents

V. Architecture of Observant Franciscan monasteries?

VII. Catalogue of Observant Franciscan monasteries

Bechyně, monastery with the church of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary

Brno, monastery with the church of St Bernardino of Siena

Bytom, monastery with the church of St Nicholas

Cieszyn, monastery with the church of the Holy Trinity

Głogów, monastery with the church of SS Peter and Paul and St Bernardino

Głubczyce, monastery with the church of St Giles and St Bernardino

Horažďovice, monastery with the church of Holy Angels

Jawor, monastery with the church of the Virgin Mary and St Andrew

Jemnice, monastery with the church of St Vitus

Jindřichův Hradec, monastery with the church of St Catherine←5 | 6→

Kadaň, monastery with the church of the Fourteen Holy Helpers

Kamenz, monastery with the church of St Anne

Karłowice, hermitage and the monastery of the Virgin Mary in the Desert

Kłodzko, monastery with the church of SS George and Adalbert

Koźle, monastery with the church of the Virgin Mary, St Francis and St Barbara

Krupka, monastery with the church of All Saints

Legnica, monastery with the church of the Holy Trinity, the Virgin Mary and St Hedwig

Nysa, monastery with the church of the Holy Cross (1475), monastery with the church of Mary Magdalene (1524)

Olomouc, monastery with the church of the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin Mary and St Bernardino

Opava, monastery with the church of St Barbara

Opole, monastery with the church of St Barbara (1473), monastery with the church of the Holy Trinity and the Virgin Mary (1517)

Plzeň, monastery with the church of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary

Prague, monastery with the church of St Ambrose

Racibórz, monastery with the church of Saints Wenceslas and Hedwig

Tachov, monastery with the church of SS Mary Magdalene and Elizabeth

Uherské Hradiště, monastery with the church of The Annunciation to the Virgin Mary

Wrocław, monastery with the church of St Bernardino of Siena

Znojmo, monastery with the church of St Francis

VIII. List of sources and literature

X. List of figures←6 | 7→

The Franciscan Observance represents the last major religious movement of the Middle Ages. It arrived in Central Europe as early as the 1430s, but its real beginnings need to be linked only to the mission activity of the Italian preacher John of Capistrano in the 1450s. Within half a century from Capistrano’s arrival, the territory of Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia was covered with a dense network of convents that soon became important religious and political centres. The fast increase in the number of new foundations in the region documents the great role the friars played in the Late Middle Ages and underlines their great popularity and influence. The architecture of the order’s convents is part of the material evidence of the phenomenon of late medieval Franciscan Observance. Its systematic research was the objective of a PhD thesis, which formed the basis for the present publication.1 Although many of the monasteries have not survived to this day, the extensive source material and the preserved fund make it possible to study their earliest history, focus on their architecture and attempt to specify and analyse it from the perspective of art history.

The territorial delimitation of the text is based on the structure of the order territory in the Late Middle Ages. The territory under study, comprising the historical lands of Bohemia, Moravia, Silesia and a part of the region of Upper Lusatia, corresponds to the territory of the independent Bohemian province that detached itself in 1469 in the form of a commissariate from the Austrian-Bohemian-Polish Observant Franciscan province. The territory developed in unified relationships and within a single political and religious milieu in the crucial period of the heyday of Observance. These common links, the close development of the individual monastic houses and shared founder personages make the 28 monasteries a group that can be subjected to a comprehensive analysis.

The work focuses on the earliest period of the history and building history of the convents starting with the arrival of the first Observants in Silesia in the 1430s, the period immediately preceding the years of Capistrano’s missionary activity. The upper boundary has been delimited by the first half of the sixteenth century, when the beginning of the Reformation entailed a deep crisis and weakening of the order along with a decline in its activity and changes in its structure. This phase was connected with the last Gothic adjustments of the convents documenting the relaxation of the order’s regulations in Moravia, with violent abolishment of monastic houses in Silesia and with an overall weakening of the order’s activity in Bohemia.

The principal part of the publication consists of alphabetical monographic entries of the monasteries (both preserved and vanished) in the delimited territory. The individual sections follow the history of the convents from their foundation to their decline or demise at the start of the Reformation period, with an emphasis put on the building development of the complexes during this period. For unpreserved buildings, the attention is paid to the study of the archival sources and the iconographic material.←7 | 8→

The starting point for the study has been an extensive field research paying attention not only to buildings belonging to the order but also to structures and works that are situated in their close proximity or linked with them by the persons of their authors and/or founders, based on the assumption that the buildings of the Observant monasteries cannot be viewed in isolation; on the contrary, that much information is brought by their incorporation in a broader regional context. The field research has been considerably complicated by the absence of modern documentation, the possibilities of surface monitoring of the structures and above all by the poor accessibility of most preserved buildings. It was very rarely possible to study all the spaces within the given complexes. Some buildings or their parts were not accessible at all and it was necessary to limit oneself to the fragmentary information that could be found in the sources, the literature and historical documentation. The situation was complicated above all in the case of living monastic premises such as the convents in Opole and Kłodzko, where the entry was prevented by the rules of seclusion. On the contrary, a repeated examination was possible in the case of several buildings. The monastic churches in Jemnice and Kamenz, Upper Lusatia, could be documented during reconstruction works, which resulted in numerous new findings.

The outcomes of the field research have been confronted with information gathered within detailed archival study, making use of the order’s source material, the funds of urban and land administrations, modern building and monument collections as well as regional museum funds. Archival materials of the order character preserved in the well-arranged provincial fund within the National Archives in Prague represented the main source of information. This archival collection includes a great part of the preserved sources of Bohemian Franciscan provenance.2 Material from the central archive has been supplemented with information from archival funds scattered in domestic and foreign institutions.3←8 | 9→

The principal source used in the work is above all the late medieval Chronica Fratrum Minorum de Observantia Provinciae Bohemiae.4 The author of a large part of the text is most probably Michael of Carinthia, who was the Bohemian provincial minister in 1526–1528 and 1531–1533.5 He wrote the chronicle between 1510 and 1521; other scribes then continued writing up the provincial history until 1553, and their work was followed by the latest records dated between 1601 and 1749. The text, describing the development of the Franciscan Observance in Italy, Capistrano’s mission and the earliest history of the Bohemian Observant vicariate, is an absolutely invaluable source for its study.6

The differences in the state of preservation of the convents, the previous scholarly interest and the level of knowledge of the buildings along with the possibilities of present research have necessitated differences in the structuring of the entries devoted to the individual monastic houses. The extent of the texts is not unified, either, depending on the quality of the buildings and, above all, on the level of preservation, the accessibility of the complex and the present state of knowledge. The initial sections of the monographic entries focus on the reconstruction of the earliest history of the convents from their foundation until their decline in activity or demise in the sixteenth century. Later history is followed only briefly where it affects the building form of the complexes in order to clarify their building analysis. The subsequent passages concentrate on the building development of the complexes in the Late Middle Ages, their form, layout and links to other architectural monuments above all within regional art. The individual catalogue entries record the existence of Late Gothic mural paintings, tombstones and moveable equipment of the monasteries that have been preserved in their originally intended places. More focused attention has not been paid to their systematic analysis and evaluation, however.

The analysis of the history and building development of the individual complexes with the use of archival and field research contained in the monographic entries can be regarded as the main result of the present work. Detailed analysis of the buildings in this extent was not carried out before for most of the localities. In the case of some buildings, this is the first monographic analysis ever. The revision of existing knowledge and passed down reports based on the study of the source material and a survey of the buildings in situ has brought much new knowledge. A thorough archival study has even provided information about the form of vanished complexes in some cases.←9 | 10→ The sum of the facts achieved can become the starting point for further specialised research. At the same time, it has created a suitable precondition for a synthesising text summing up the fundamental points of the issues under study.

The monographic chapters are preceded by a text summarising the historical context of the arrival of the Observant Franciscan community in the territory under study, its quick rise and fall with the onset of the Reformation. The order history is followed by chapters describing the regularities of the process of the foundation and construction of convents, the order rules limiting artistic production and the character of the architecture of order buildings. Comparison material for the Bohemian context has been studied above all in the territories of Austria, Poland, Germany and Hungary, which are linked to the monasteries of the Bohemian vicariate by a common history and close artistic development.

The motivation for the research came from the marginal interest that had been paid to the theme by previous researchers. The architecture of Observant Franciscan monasteries long remained unspecified by literature dealing with medieval art. The scanty mentions of preserved buildings were often accompanied by a negative assessment. The monuments were described as examples of low creative effort reflected above all in imitation of early models that had been elaborated in the architecture of the Friars Minor back in the thirteenth century. The study of preserved Observant Franciscan monasteries, however, has shown their close interconnection with regional architecture stemming from their great dependence on their founders and benefactors. In the end, it has led to the statement that more than any general order regulations or passed down conservativeness of the forms, Observant buildings reflect the possibilities of their founders and the regional styles of the implementing workshops.

![]()

Research into the historical, philosophical and theological aspects of medieval Franciscan movement has a long tradition. The first scientific editions of order sources appeared as soon as the late eighteenth century,7 followed in subsequent centuries by numerous monographic studies, specialised journals8 and gradually emerging scientific workplaces9 focused on the research of the Friars Minor. Research info the Franciscan Observance developed above all after the Second World War and continues in present European historical research, which examines various issues connected with the order’s affairs, concentrating quite generally on the history of the order10 or on←10 | 11→ specific topics within its structure such as the questions of the education11 or national disputes.12 The individual order territories, provinces, are subjected to thorough research in present-day Germany – and particularly Saxony13 – as well as in Hungary14 and Switzerland.15 Historical works studying the issues connected with the convents in Austria16 and present-day Poland17 are of particular importance for the research of the Bohemian order territory, as these territories comprised a single order province together with the monasteries of the Bohemian vicariate until 1467. They provide not only important comparison material but also many reports directly relating to the situation in the Bohemian order territory.

Czech historiography focused on the history of the Observance is extensive.18 Since the nineteenth century, a special attention has been paid to John of Capistrano’s mission to Central Europe.19 The first synoptic history of the Franciscan Observance in the Lands of the Bohemian Crown was published by the Franciscan historian Klemens Minařík,20 whose texts referred to late medieval sources for the first time. His detailed scholarly work to which he dedicated a great part of his life is reflected also in the semi-finished studies, preparatory translations and notes he left in his inheritance.21 Minařík’s works represent the basis for research into the Franciscan Observance that directed Czech historiography back to source study. German Franciscan Lucius Teichmann also proceeded from archival research. In his studies, he focused above all on the Silesian part of the Bohemian Observant vicariate and particularly on the←11 | 12→ national disputes that developed in that region.22 Teichmann’s dissertation thesis Die Franziskaner-Observanten in Schlesien vor der Reformation published in 1934 was of fundamental importance, as were numerous later texts in which the author used medieval and above all Baroque source material.23 Teichmann was followed in the Silesian region in the 1990s by historian from Wrocław Gabriela Wąs, who concentrated above all on the relationships between the Observants and the urban milieu at the time of the beginning of the Reformation.24 She drew on later archival materials, however, without the knowledge of order documentation from the Bohemian and Moravian archives.

An important study by František Šmahel set the research into Bohemian Franciscan Observance into a wider ecclesiastical political and cultural context. Although the text only draws upon earlier literature and suffers from numerous imprecisions, the synoptic summary of the results of previous research and the systematic approach pointed out the importance of the theme in the context of Central European history.25 A similar general impact had also studies by Petr Hlaváček, which were focused on a number of topics of late medieval Observance, particularly the brothers’ relations to the Bohemian and European Reformation, the studies and education and the rampant national rivalry within the Bohemian vicariate.26 The information from the publication Čeští františkáni na přelomu středověku a novověku [Bohemian Franciscans in the Late Middle Ages and early Modern Era], which summarises the earliest history of the Observants’ activity in the land, has been recently gradually accompanied by partial studies published above all within the series Historia Franciscana.27

While historical research into the Franciscan Observance has developed thoroughly, the investigation of the artistic manifestations of the order society stands rather in its beginnings. The architecture of the Observant convents specifically remains on the very edge, not having been described in a more complex manner yet. Only marginal attention has been paid to the architecture of Observant Franciscan monasteries within the research into mendicant architecture. The foundations of the research into the architecture of the mendicant orders have been developed above all by German and Austrian scholars.28 Polish literature has also focused on it, as has Czech research,←12 | 13→ albeit less systematically.29 Many researchers conclude their overviews already in the fourteenth century, which means that they do not get as far as the Observant Franciscan architecture, and we cannot refer to them even as methodological models. These publications offered the basic characterisation of the order’s architecture. In essence, they only differ in the greater or smaller role they ascribe to the Franciscan order in the formation of the architecture. Especially in the earlier titles, the analyses lack a broader context, which was often obscured by an effort to categorise selected examples of mendicant buildings into typological and development lines. The authors examine the typological development of the buildings and classify them according to formal schemes including the layout, the vault system or even the forms of pillars used. This concept of art history does not take much account of historical reality. The simultaneity and multiformity of the processes are reduced into a very simplified scheme that suggests a homogeneous and therefore ahistorical development of mendicant architecture. Only the latest contributions consider the rightfulness of the general term “mendicant architecture” and the importance of its research. Schenkluhn pays particular attention to earlier methodological procedures, pointing out the groundlessness of the classification contained in earlier research.30 In his monograph, he shows that the mendicant orders built according to local and very different preconditions in various parts of Europe.

We can say that the Observant buildings stood on the margin of systematically conceived research for a long time. They are only sporadically part of complex publications dealing with medieval architecture or with the architecture of the mendicant orders. Selected convents are mentioned rather haphazardly, often without discrimination between Observant and Conventual houses. Where Observant buildings do appear in the literature, they are rarely free of a negative assessment. The adjectives most often used in connection with their architecture are retardant or traditionalist. Order buildings of the Capistrano movement were described for the first time and assessed in the above-mentioned spirit by Kurt Donin within a publication discussing mendicant architecture in Austria.31 He focused on several buildings in the Austrian province, regarding their features as a deliberate imitation of thirteenth-century architecture of the mendicant orders. According to Donin, the orientation to old models and traditionalism was a logical consequence of the Observant movement’s return to the asceticism of the earliest period of St Francis. Polish or Hungarian research ponder the Observant architecture in a similar spirit.32

The architecture of transalpine Observant Franciscan monasteries had not been systematically evaluated until a study of Polish convents worked out by Marian Kutzner.33←13 | 14→ He showed for the first time that rather than regarding it as backward, the architecture of the order’s buildings should be studied within the context of regional architecture and through the prism of the functions it was supposed to fulfil. Kutzner used a rich archival material to reconstruct the Observants’ building practice in Poland. Preserved necrologies provided him with information about the deceased authors, and monastic chronicles about the processes of the construction and their regularities. In the examples of Observant architecture, Kutzner sees links stemming from the effort to rigorously stick to the order’s principles. He studies the architectural character of the buildings in an effort to find a common element. He sees a typical feature of Observant buildings in the development of the model of earlier architecture, which combines simple stereotomic bodies that characterise the individual parts. At the same time, however, he describes the order’s architecture as rich, ornamental and, in many cases, modern and demanding. Kutzner observes particular closeness to regional architecture around 1500, when the regulations were relaxed and the constructions more subjected to the building practice of the donors. He traces a local style in the monastic buildings stemming from the growing dependence of the Franciscan order on the benefactors. Kutzner links the Observants to mass, vernacular art, putting it in contrast to the early beginnings of the order, when the brothers oriented themselves on the elites.34

Apart from a general view of the development of the order’s architecture, there is one phenomenon in the sphere of Observant architecture that has been studied in more detail – the use and spread of diamond vaults. The question of the development and use of the diamond vaults has been discussed from the beginning within the analysis, specification and description of the vaulting technique. The initial centre was sought and the chronological line of the buildings reconstructed, as was the mechanism of the spread of this type of vaulting in view of its temporary and spatially limited occurrence. While the research has reached an agreement concerning the question of the source building,35 the system of processes of the spread of the new type of vault remains open in details. The occurrence of diamond vaults or elements that accompany them (curtain arches, diamond-shaped decorations) in the monasteries of the Friars Minor has led some researchers to look for the role the Observants played in their spreading and application. However, this research paid no attention to the order and founder context or to the friars’ possibilities from the viewpoint of the funding and autonomy. Moreover, it did not consistently examine whether the monastic buildings←14 | 15→ analysed by the researchers actually belonged to the Observants, to the Conventuals or, in the case of Saxony, to the Reformates – Martinians.

The spread of the diamond vault was first linked to the Franciscans in Hermann Meuche’s dissertation thesis in 1958.36 In the text, Meuche follows the development of the diamond vault in all influenced territories, clearly showing that Bohemian regions took over the diamond vaults from Saxony. According to him, the initiatory construction was the realisation of the monastery in Kadaň, from where, thanks to the Franciscan order, diamond vaults expanded first among monastic buildings and then also in the architecture outside the order.

Milada Radová, who devoted a great part of her scientific work to the importance of the diamond vault, published her first summaries in the same year as Meuche.37 She described the development of the diamond vault in Bohemia with regard to the links between the individual investors, explaining the use of the vaults in Kadaň and Bechyně, consequential in terms of time, by natural collaboration between the newly founded Observant Franciscan monasteries. She expressed more or less the same views also in later journal studies and a monograph, which were published independently or with her husband Oldřich.38 Apart from family and trade links between the donors, Radová and Rada see precisely the relations between Franciscan monasteries in Saxony and Bohemia behind the spread of the diamond vault. Regrettably, all works by Radová and Rada suffer from mistakes stemming from limited knowledge of the order organisation and often resulting in misleading conclusions.39

Opinions repeating the standpoints of Radová and Rada can be frequently found in both domestic and foreign literature.40 Some authors, moreover, support the brothers’ active involvement in the spread of the new vault form by an effort to link diamond vaulting to a reflection of the order’s spirituality. In the vaults, they reveal the order’s endeavour to optically express the concept of poverty by the use of a monotonous form of vaulting.41 Bischoff was the first to express a negative opinion concerning←15 | 16→ these theories.42 He doubts that the Saxon Observants could be attributed an active role in the spread of the diamond vault. Likewise, he points out the improbability of Meuche’s thesis, which ascribes a large number of vaults in Bohemia practically to a single work group. According to the author, the initiatory role in the spread of the vaults was played by noble families, which gave the impulse to the takeover of the Saxon forms and saw to their expansion.

The latest research into the artistic manifestations in the sphere of the Franciscan Observance continues developing above all abroad, particularly in Poland and Germany.43 Rather than systematically studying Observant Franciscan building monuments, however, it pays attention to artistic manifestations within the order. The painting decoration of rood screens in Observant Franciscan monasteries of the Milan province,44 the personages of the order’s authors,45 late medieval iconography of Observant saints or the general symbolism of the order46 have all been studied in detail. Czech research in this sphere has focused above all on funeral monuments in the convents.47

Jakub Kostowski above all has paid systematic attention to research into art from the milieu of the Observant convents and to the general iconographic concepts of the decoration of their churches.48 Italian research examines primarily north Italian Observant architecture,49 but the monographs and journal studies offer a comparison to the transalpine regions only as regards the general order principles applied to the architecture. The buildings themselves do not offer many analogies to the milieu of Central Europe, not even as regards the layout and the functional use of the spaces. Modern research studying the patronage and seeking a wider context of the origin of the particular Observant convents and of the works connected with them thus remains the main source of inspiration.50←16 | 17→

1 The PhD thesis Architecture of Franciscan Observant Monasteries in Bohemia, Moravia, Silesia and Upper Lusatia in the Second Half of the 15th Century was completed early in 2016 and defended in September of that year at the Institute of Art History of Charles University in Prague. The text was shortened and prepared for printing in the following year.

2 The fund contains hundreds of original deeds, manuscript books and more than two hundred boxes of documents that provide an important source basis for the study. The collection also includes valuable iconographic material and, in some cases, also plan documentation of the buildings. The crucial task was to map the content of the original deeds, which were partially accessible online on the Manuscriptorium website, along with detailed information from the Baroque chronicles of the individual monastic houses and the provincial chronicle by Bernard Sannig, which is preserved in several hand-written copies in the archive. National Archives (NA) in Prague, Franciscans – the Provinciate and Convents, Prague (1283–1950), books 17, 20, 21, Bernard SANNIG: Chronica de origine et constitutione provinciae Bohemiae Ordinis Fratrum Minorum (1678). On the organisation and structure of the archival funds, see SVÁTEK 1970, 548–550, 608; ELBEL 2001, 97–99. Other major parts of the archival material of order character are included in several separate funds within the National Archives in Prague (Franciscan Order Kadaň (1450) 1529–1948, Franciscan Order in Bechyně (1431) 1490–1950, Discalced Franciscan Order in Jindřichův Hradec 1668–1948), as well as in the Moravian Provincial Archives (MPA) in Brno (Franciscans Dačice, Franciscans Znojmo, Franciscans Uherské Hradiště) and the State Regional Archives Plzeň (Franciscans Tachov). Some Baroque documents concerning the monasteries can be found in library collections (Education and Research Library of the Plzeň Region, University Library in Wrocław).

3 Regional archives have been used along with the archives of regional and town museums, preservation and municipal authorities and private entities.

Details

- Pages

- 536

- Publication Year

- 2018

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783631774083

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783631775011

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783631775028

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783631775035

- DOI

- 10.3726/b14935

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2019 (January)

- Keywords

- Late Gothic Medieval Art Artistic Patronage Church History Religious Orders Diamond Vault

- Published

- Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Warszawa, Wien, 2018. 535 pp., 341 fig. b/w

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG