For the Love of Science

The Correspondence of J. H. de Magellan (1722–1790), in two volumes

Summary

For ordering the hardback version please contact order@peterlang.com. (Retail Price: 239,90$, 162£), For puchasing the ebook please go to 978-3-0343-3721-2

From his base in late eighteenth-century London, J. H. de Magellan corresponded with leading scientists and others in many parts of Europe, informing them of developments in British science and technology in the early years of the Industrial and Agricultural Revolutions. Intelligent, ingenious and interested in everything going on around him, Magellan was deeply committed to the Enlightenment view that the benefits flowing from human ingenuity should be made available to all mankind. Well connected both socially and within the scientific community, he made it his business to keep himself well informed about the latest advances in science and technology, and to pass on what he learned. In this remarkable correspondence, the metaphorical Republic of Letters becomes real, offering us a fascinating new view of pan-European intellectual and scientific life. Major themes are developments in scientific instrumentation and in chemistry, and the spread of steam-engine technology from England to the rest of Europe. Ranging from Stockholm and St Petersburg to Spain, Portugal and Philadelphia, the list of Magellan’s correspondents is a roll-call of the scientific luminaries of the age.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the Editors

- About the Book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- Volume I

- Introduction

- Acknowledgements

- Editorial Conventions

- Illustrations

- Calendar of Correspondence

- Correspondence

- 59.05.21-79.05.02

- Volume 2

- Correspondence

- 79.05.13-89.12.28

- Undated letters

- Bibliography

- Index

Roderick W. Home, Isabel M. Malaquias & Manuel F. Thomaz (eds.)

For the Love of Science

The Correspondence of J. H. de Magellan (1722–1790)

Vol. 1

The surviving correspondence of the abbé J. H. de Magellan (1722-1790) that is brought together for the first time in this edition is one of the most interesting science-related correspondences of the late eighteenth century.1 Magellan was not himself a front-rank contributor to scientific thought. He was, however, intelligent, ingenious and interested in everything going on around him, and he was also very well connected, being acquainted with most of the leading men of science of his day and the leading instrument-makers, as well as members of the upper classes, including even the aristocracy and higher nobility, in several European countries. Moreover, he made it his business to keep himself well informed about the latest scientific and technical developments, and to pass on the information to his correspondents all over Europe. For, as we shall see, his letter-writing served a more than social purpose, it also brought him an income.

Magellan and his correspondence in fact occupy an important moment in the history of science. As the scientific world expanded during the second half of the eighteenth century, it became increasingly dependent on the efficient interchange of techniques and information between the growing numbers of people involved in scientific work. Magellan represents an intermediate state between an earlier and more leisurely period in science where information travelled relatively slowly between the small number of individuals involved, and the new, enlarged community that began to look for a much more rapid dissemination of news. Eventually the needs of that community were met by the development of a new kind of scientific journal, epitomized by the one founded by François Rozier in Paris in 1772, that appeared much more frequently than the old-style volumes of academic proceedings and carried letters and short reports rather than full-scale memoirs. For a brief moment, until those journals took over, there was a gap that Magellan’s incessant letter-writing helped to plug. His correspondence is thus of much more than biographical interest, it offers us a window on to a wide range of late-eighteenth-century scientific practice and technological innovation. ← 1 | 2 →

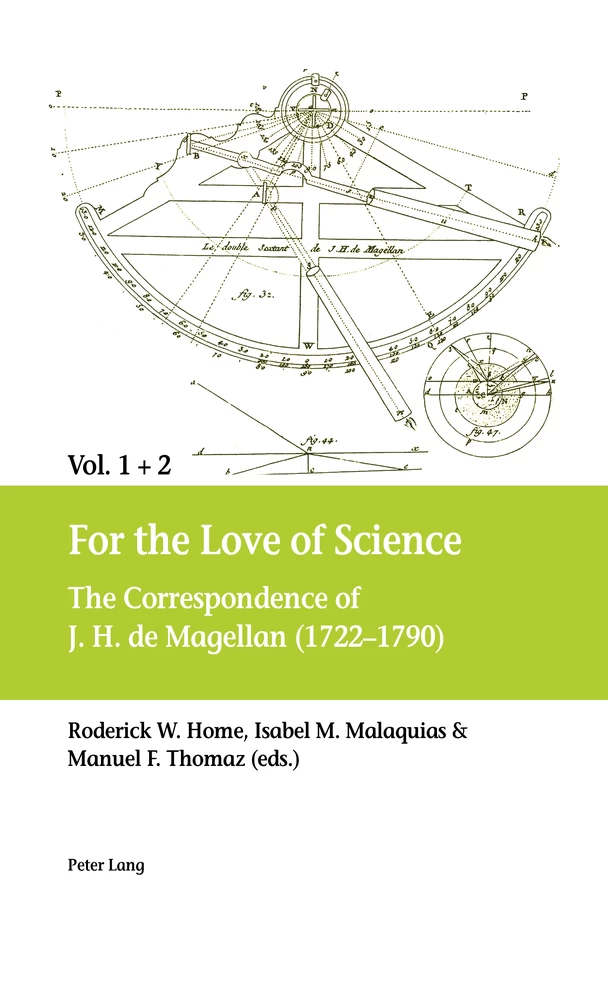

Magellan himself was especially interested in the development of scientific instruments, and most of his own publications, and also many of his letters, were devoted to describing improvements he had devised to one or another measuring device. Some of these improvements were taken up by the English instrument-makers whose workshops he frequented, who led the world at the time. The exciting developments taking place in chemistry in those years – especially in relation to the chemistry of gases – also figure large in the correspondence.2 As we shall see, Magellan played a significant part in these developments by serving as one of the principal conduits by which information about the latest discoveries flowed between the leading French and British chemists of the day. He also took a close interest in the dramatic changes taking place in British agricultural practice in these years and numbered leading reformers such as Arthur Young and John Arbuthnot among his friends; and he went out of his way to provoke discussion of these matters among his acquaintances on the Continent. Letters that he wrote in his capacity as Continental agent for the pioneer Birmingham industrialists Matthew Boulton and James Watt shed new light on the spread of steam-engine technology, and the industrial revolution that this underpinned, from England to the rest of Europe. However, these are but some of the highlights of the correspondence; Magellan’s letters range much more widely in their subject-matter and, in the process, offer us a fascinating new view of the intellectual life of his day.

Generally speaking, Magellan wrote in French, the lingua franca of the day; but when he wrote to his Portuguese contacts, he naturally wrote in Portuguese, and to British correspondents and to those in what had been Britain’s colonies in North America, he of course wrote in English. In this remarkable correspondence, the metaphorical Republic of Letters becomes real. Yet the correspondence that has survived, rich though it is, is far from complete. In the letters that we have, many others are referred to that are now missing; moreover, we know that many letters perished, along with other papers, in a fire in Magellan’s lodgings in December 1772. ← 2 | 3 →

Early years

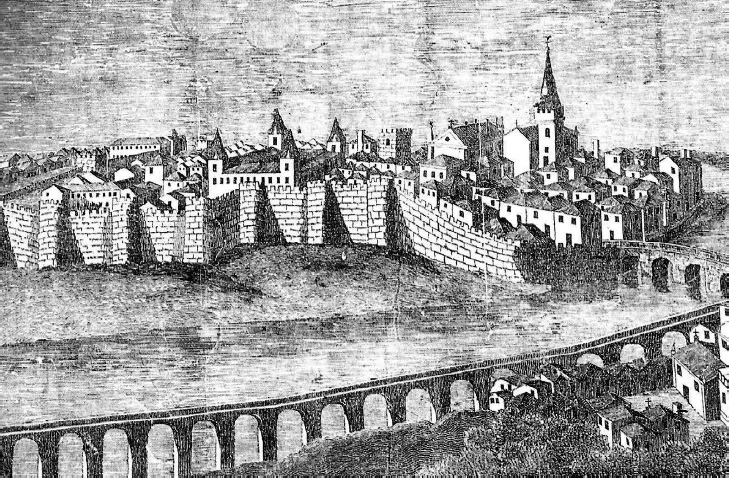

Magellan was born on 4 November 1722 in the small town of Aveiro in northern Portugal, a country without a solid tradition in science, especially in the experimental sciences. His family background is not disclosed or even referred to in his correspondence. However, in a couple of his publications he claimed a relationship with the famous sixteenth-century navigator Ferdinand de Magellan and, in confirmation of this, from national and parochial archives in Portugal his ancestry has been traced to the explorer’s younger brother.3 The fact that he never refers to his parents is comprehensible because he never knew them: his mother died five days after he was born and his father died less than a year later. He was their only ← 3 | 4 → child.4 During his earliest years he was probably looked after by relatives. Though of a noble line, his family was not wealthy. However, he inherited several properties and the income from these enabled him to be enrolled at 11 years of age in the Colégio da Sapiência, a college of the Augustinian Monastery of the Holy Cross in Coimbra famous throughout Portugal for its rigorous teaching and its modern and well-stocked library where even the more modern scientific and philosophical books could be read. On 23 April 1743, at the age of 21, Magellan took his vows of poverty and chastity and joined the Augustinian Order, taking the name Frei João de Nossa Senhora do Desterro (Fr. Joannes a Domina Nostra de Exilio).5 On 7 April 1744 he became a regular canon, which entitled him to use the title “Dom” instead of “Friar”. Then in 1751, at the age of 29, he was ordained a priest in the Augustinian Order. For at least two years he was enrolled as a student in the Faculty of Canon Law at the neighbouring University of Coimbra, Portugal’s principal university at the time.6 However, he is not recorded as having sat the examinations and in any event his studies there would not have contributed in any way to his knowledge of current science. Not only was science not a part of the curriculum in canon law, the university as a whole remained mired in the ancient tradition: no modern science was taught in any part of it until after the reform of the institution in 1772, long after Magellan had left Coimbra.

Somehow, nevertheless, Magellan managed during the period of more than twenty years that he spent with the Augustinians in Coimbra to develop a taste for science and a good acquaintance with it. His preference for science may be inferred from his being the person designated to assist the French astronomer Gabriel de Bory when he visited Coimbra in 1753. Bory went to Portugal to observe the total solar eclipse that was calculated to be visible at Aveiro in October of that year. Once the eclipse had passed, Bory travelled to Coimbra, where he visited the Augustinians. It was Magellan, we learn from the report that Bory later presented to his colleagues in Paris, who showed him around “that magnificent house”.7 The monastery, Bory reported, was a closed community and the monks adhered strictly to this; it was their doing so, he thought, that had led them to cultivate the sciences. ← 4 | 5 →

Not long after Bory’s visit and perhaps partly inspired by it, Magellan apparently sought permission to leave the congregation under the terms of a general dispensation issued by Pope Benedict XIV as part of a wider reform of the religious orders in Portugal. We have not found the documentation relating to Magellan’s leaving the Order but it would presumably have reflected a lack of vocation on his part.8 Under the terms of a decree issued some years earlier by the Reformer General appointed to oversee the Augustinians of Santa Cruz, canons who opted to leave were entitled to receive a pension of Rs. 30,0009 per annum (later increased to Rs. 36,000 per annum) from the congregation.10 They were still regarded as priests – Magellan was generally referred to as abbé – and were required to make themselves available to the highest church official (the bishop or his representative) in the town in which they took up residence. For some reason, for over twenty years Magellan did not receive the pension to which he was entitled. When he did eventually receive what was owed to him, he presented it to the recently founded Lisbon Academy of Sciences, of which he had been appointed a member, to endow a prize for agricultural improvements.11

Finding a new career

Until recently, little was known of Magellan’s whereabouts during his first years outside the monastery. Neither did we know how he supported himself, but presumed that he must have been receiving sufficient income from his estates or elsewhere to maintain himself in a respectable lifestyle. He later stated on a couple of occasions that he was in Lisbon on 1 November 1755 and witnessed the destruction caused by the great earthquake and subsequent tsunami that struck the city that day.12 We also knew that he ← 5 | 6 → afterwards left Portugal, supposedly on a “tour philosophique” with the stated aim of becoming better acquainted with the scientific and technical advances being made in other parts of Europe. Throughout his life, these were the things that interested him most. By contrast, music and the fine arts figure scarcely at all in his surviving letters – although, astonishingly, we learn from his will, drawn up in 1788, that he owned a piano, a newly developed instrument at the time and a rather expensive item then as now.13

Recently, a fortunate reading of London’s Morning Herald newspaper, founded in 1780, brought to our attention a previously unremarked column entitled “Memoirs of Eminent Living Persons” that appeared from time to time in this journal in its earliest days. One such memoir, seemingly one of the first written specifically for the journal, was devoted to “Hyacinth de Magellan”; and even though this includes some inaccuracies, it also includes enough pertinent detail that there can be no doubt that it was compiled by whoever wrote it from information supplied by Magellan himself.14 The inaccuracies, which relate chiefly to chronology, are presumably a result of the author’s running together incorrectly things that Magellan had told him. However, their presence means that we must be cautious about other things that are said in the article, that may also incorporate misunderstandings on the author’s part.

Subject to that qualification, we learn from the article that Magellan fled Portugal when a person with whom he had been associating was arrested:

Magellan as he walked the street was told of his friend’s fate, and knowing that it was an universal rule with the minister [the Marquis de Pombal] to imprison every man who had ever been in correspondence with any person he seized, and the unhappy innocent having letters of his in his possession, immediately went home, put up what money and valuables he had by him, and without the delay of an instant, set off for Spain.

Magellan’s hasty departure reduced him, we are told, to poverty, and he was forced to travel on foot, walking all the way to Madrid. Here, fortunately, he met a man who had known him in earlier life as a respectable person, who provided him with introductions that enabled him to live decently. He stayed there for about a year and a half, long enough to learn Spanish, before moving on, still on foot because he remained very poor but carrying letters of recommendation from his Spanish friends. His route ← 6 | 7 → took him across Spain and southern France to Marseilles “where he staid long enough upon his recommendations, and his unremitting industry in teaching Latin and Portuguese, to write to Paris”. The reply he received was not encouraging, however, so he continued instead to Italy, first to Turin and then through Lombardy to Rome “where his letters procured him some attention”. He spent two years in Rome, teaching natural philosophy and mechanics as well as Latin and Portuguese, while learning Italian (“which language he has ever since spoken better than any other”) and “studying those arts and sciences, by which he hoped to support himself in future”. Eventually he moved on again, travelling to Paris via Geneva where he stayed “long enough to make himself a master of all they knew in watch making” and where his mechanical abilities created such a good impression that one of the town’s master watchmakers offered him a place at his house and table for as long as he liked to stay. Paris, however, proved a disappointment, and so after staying “long enough for acquiring the French tongue” and to meet the famous philosopher-mathematician Jean d’Alembert “who shewed him many civilities on finding that he was no inconsiderable mathematician”, he moved on to London. There is no mention of his ever returning to Portugal, even though we know he did so, in June 1761, before ever he settled in London.15

Magellan certainly visited Rome at some stage during his travels16 but otherwise there is no supporting evidence for the story just told until 1759, when we know he was in Paris for a while. No documents of any kind in his hand from earlier in his life have been found. The Portuguese Minister in Paris, Mgr. Pedro da Costa de Almeida Salema, reported that he succoured Magellan, who had reached Paris in dire need, but always kept a wary eye on him “because he touched and wanted to know our business more than it was lawful to ask”.17 His earliest surviving letters date from this time, when he was already 37 years old and had been out of the monastery in Coimbra for several years. From one of these letters we learn that he was living at the time at the very respectable Hôtel des Prouvaires, ← 7 | 8 → in the St Eustache quarter of the city.18 In addition, we learn from one of Magellan’s publications from later in his life that he visited the workshop of the well-known Parisian instrument-maker Claude-Siméon Passement at this period.19 There is, however, no mention in any other source we have found of his meeting d’Alembert.

The correspondence that has survived from Magellan’s time in Paris – fragments in each case rather than full letters – reveal that he had established contact with some of the leading astronomers in the French capital and was making himself useful to them by translating into French reports of astronomical observations made in Portugal. Almost certainly he was introduced into Parisian astronomical circles by his old acquaintance, Gabriel de Bory. Now, Magellan also established links with Joseph-Nicolas Delisle, who was perhaps the leading French astronomer of the day, and Charles Messier with whom he was subsequently to correspond for many years. The observations he passed on were due to the Oratorian priest Jean Chevalier, an enthusiast for astronomy who later moved to Brussels and became Keeper of the Royal Library there. Chevalier had been a corresponding member of the Académie Royale des Sciences since 1753, and Delisle was his designated correspondent there. The fragments that have survived all report observations of comets. Despite Chevalier’s failure to provide precise information about the position and motion of the comets in question, such reports would have been particularly welcomed by Messier, who had already embarked on what was to become a life-long career as a comet-hunter.

Magellan while in Paris also met and became close friends with the distinguished Portuguese physician and man of letters, António Nunes Ribeiro Sanches (1699-1783). Sanches had studied medicine at Leiden under Herman Boerhaave and been recommended by him to a position in Russia, where he rose to become in due course personal physician to the Empress Elisabeth. In 1747, the Empress had allowed him to retire and leave Russia, and he had settled in Paris where he was later supported in part by a pension from the Portuguese Government that after he died was transferred to Magellan.20 His patronage was crucial to the subsequent development ← 8 | 9 → of Magellan’s career, for he was able to introduce Magellan into both the topmost levels of Parisian society and scientific and philosophical circles in the capital.

Magellan was probably still in Paris in April 1760, when the Journal étranger published his lengthy summary for French readers of an account published in Portugal of the measures taken by the authorities there to restore order after the Lisbon earthquake, as well as to establish the plans and to provide the means to rebuild the shattered city. The account, supposedly written by Francisco José Freire, was actually the work of Portugal’s reforming but increasingly despotic Prime Minister, Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo, Count of Oeiras (later Marquis de Pombal). Not surprisingly, it was lavish in its praise for the government’s response to the crisis, and so, too, was Magellan’s summary.

Other publications by Magellan during this period, anti-Jesuit in flavour, suggest that he would have been very much in sympathy with Pombal’s campaign to break the power of the Jesuits, longstanding rivals of the Augustinians, over civil and political life in Portugal. He may even have been a pawn in that campaign. One publication was a translation into Portuguese, published initially in Paris and later in Lisbon, of the Greek grammar used by the Jesuits’ chief rivals in France, the Jansenists, in their famous Parisian college of Port-Royal.21 Another, also published in Paris, was a new edition of a seventeenth-century biography of a famous pre-Jesuit Portuguese theologian.22 A third, much more potent from a political point of view, was a Portuguese translation, published in Lisbon and dedicated to Pombal, of a virulent anti-Jesuit work by a French Capuchin monk generally known as the abbé Platel, whom the Prime Minister had invited to Portugal a couple of years earlier.23

Magellan’s preface to the Greek grammar sheds an interesting light on his manner of working. In order to learn more about the pronunciation of the Greek language, he said, he had profited whenever he could, in different parts of Europe, from any contacts he could make with Greek nationals or people recommended to him who had travelled in Greece.24

Whether or not Magellan was a pawn in Pombal’s campaign against the Jesuits, it seems that once he returned to Portugal, he soon became disillu ← 9 | 10 → sioned with Pombal’s despotic behaviour and by early 1762 he was telling Sanches that he had decided to leave again and settle in a country where he could live more freely – in Paris, perhaps, or England or Italy, particularly Venice. Before leaving, however, he spent considerable time and energy in trying, apparently at some risk to himself, to resolve problems that Sanches was having with the Portuguese authorities.25 It was probably on this account that Sanches afterwards paid him an annual pension that Magellan continued to receive until Sanches’ death, more than twenty years later.

On leaving Portugal, Magellan once more made his way to Paris. He later claimed to have contemplated settling in America.26 Instead, however, with Sanches’ advice and assistance he moved soon afterwards to London where he was to make his home for the rest of his life, interspersed by regular visits to Paris and the Low Countries.

Settling in London

In London, Magellan gradually worked his way into the heart of the British scientific community centred on the Royal Society of London. As we learn from the Society’s Journal Book, he took to attending the Society’s meetings regularly as a guest of one or other of the Fellows – he first attended a meeting on 10 November 1763 – and in due course he began presenting reports to the meetings, many of these being extracts from letters he had received from his astronomer friends in Paris with details of their latest observations. Most notably, most of the French observations of the transit of Venus across the face of the Sun in 1768 reached the Royal Society through Magellan. The Society’s meetings also became a principal source of the scientific news that he took to spreading to his ever-widening circle of correspondents on the Continent.

One of Magellan’s earliest contacts in the Royal Society was Emanuel Mendes da Costa (1717-1791), the English-born son of a Sephardic Jew of Portuguese descent who had settled in England in the 1690s. Da Costa was an enthusiastic naturalist and an expert on fossils who had been elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1747 and in February 1763 was appointed its clerk, librarian and housekeeper. (He was later, however, dismissed and ← 10 | 11 → sent to jail for defrauding the Society.) Magellan’s earliest surviving letters after he arrived in London show him facilitating da Costa’s contacts, on both the Society’s behalf and his own, with naturalists in Portugal.

London was at this period the world’s leading centre for the manufacture of scientific instruments, and Magellan quickly became a familiar figure in the workshops of the leading makers. As we shall discuss further below, this not only enabled him to indulge his passion for invention, the connections that he established became a means by which he could earn significant sums of money. In some cases, those business connections developed into personal friendships sufficiently close that when, for example, near the end of his life, Magellan drew up his will, the witnesses to his signature were the renowned instrument makers John and Edward Troughton and the well-known optician Thomas Hennings.

One of those with whom Magellan became associated at an early stage was Henry Pyefinch, a maker of optical and mathematical instruments with whom Magellan appears to have lived for a time, and with whom he collaborated in developing an improved “barothermometer” or “aerostathmion” that in due course they patented. Magellan presented a description of this device to the Royal Society in mid-1765 after reading a paper to the Society earlier that year in which he discussed the deficiencies of existing barometers. His reading of his new paper was not, however, a success, perhaps partly because of Magellan’s still imperfect English (which he would no doubt also have spoken with a thick accent at the time) but chiefly because of the minute and tedious detail into which he entered in explaining the operation of the instrument. His reading extended over two meetings of the Society, on 13 and 20 June 1765, yet still he had not reached the end. No further time was allocated to him, however, until after he submitted a much-abbreviated version of the paper in the following November, and the paper was never published in the Society’s Philosophical Transactions. In response to the protests of Magellan and his friends about the way he had been treated, the Society introduced new procedures to ensure that henceforth papers were read in the order in which they were received by the Secretaries; but the Secretaries were also instructed to peruse all papers before they were read, thus introducing a degree of quality control that if in place earlier might have led to Magellan’s being required to edit his paper before reading it.

Some years later, Magellan again ran into difficulties when he presented a paper to the Royal Society. On this occasion the paper, which described improvements Magellan had devised for angle-measuring instruments such as octants and sextants, was subjected to heavy criticism by the ← 11 | 12 → Astronomer Royal, Nevil Maskelyne, who favoured alternative improvements devised by the optical instrument-maker Peter Dollond. Dollond had patented an articulated arm to support the side mirrors of the instruments, whereas Magellan’s proposal made use of a standard toothed circle to direct the mirrors. Maskelyne’s criticism, which Magellan regarded as self-interested and completely unjustified, was sufficient to ensure that Magellan’s paper did not appear in the Philosophical Transactions, whereupon he arranged for it to be printed separately instead, in London but in French for the benefit of the international market in scientific instruments.27 Other works of his were later published in the same way as slim books, in French, thirty or forty pages long;28 indeed, Magellan seems at this time to have abandoned all idea of having his work published by the Royal Society. Most of these publications were concerned with improvements to various scientific instruments, several of which were taken up by the leading instrument-makers of the day. One tract described Magellan’s improved method of aerating artificial soda water, which was widely adopted. Perhaps the most influential work from a scientific point of view was his account, published in 1780 and discussed further below, of recent British advances in the study of heat, that was instrumental in bringing these to the attention of Lavoisier and the other leading French chemists with epoch-making consequences.

Despite these occasional setbacks, Magellan continued attending meetings of the Royal Society very regularly and on 21 April 1774 he was elected a Fellow on the home list, that is, as a “domestic” rather than a foreign member. The signatories on his nomination certificate included such luminaries as Benjamin Franklin, Joseph Priestley, Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander and, as Magellan later reported to the Genevan astronomer Jacques-André Mallet, an overwhelming majority of votes were cast in his favour despite the efforts of a few members who, Magellan said, caballed against him – eight, he reported, as against 62 who voted in his favour.29 ← 12 | 13 →

What led a group of Fellows, albeit a small one, to oppose Magellan’s election is not known. His being a Catholic priest is a possible explanation,30 given the staunchly anti-Catholic views of many Englishmen at the time, although other priests – the Jesuit Roger Boscovich, for example – had been elected before him. Magellan, however, had “form” in this regard, because in 1768 he had been indicted, with four others, by an informer before the Court of King’s Bench at Westminster, accused of being a priest and having said mass – this being a felony in England at the time.31 Though the case collapsed on a legal technicality and he was acquitted, mud may have stuck, at least in the eyes of those holding more extreme anti-Catholic views.

Joseph Banks’s signing Magellan’s nomination form is but one indication that the two men were on good terms at the time. Earlier, when it appeared that Banks, having accompanied James Cook on his first great voyage of discovery, 1768-70, would also accompany him on his next voyage, Magellan applied to join Banks’s party.32 Some years afterwards, following the death of the French botanist Jean Aublet, he facilitated Banks’s purchasing of Aublet’s notable herbarium, and he diligently passed on the congratulations of several of his foreign correspondents when Banks was elected President of the Royal Society in 1778.33 Later, however, the relationship between the two men soured as Magellan became disenchanted, as did a number of other Fellows of the Society, with Banks’s leadership. When matters came to a head in early 1784 with an open challenge to Banks’s authority by a group of “mathematician” Fellows, Magellan was very much on the side of the dissidents, broadcasting their complaints about “this arrogant (orgueilleux) President” to his correspondents abroad.34 Even after the initial challenge failed, he continued to look forward – in vain, as it turned out – to a new President’s being elected at the Society’s next anniversary meeting, when the election of officebearers was traditionally held.35 He seems never to have reconciled himself thereafter ← 13 | 14 → to Banks’s continuing in office but was reduced to presenting the Society in a very jaundiced light in his letters, while sniping ineffectually at the President and his supporters.36

In addition to becoming involved with the Royal Society soon after he settled in London, Magellan became a devotee of the Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce. Formed only a few years earlier, in 1754, this body (now the Royal Society of Arts) provided a forum at which inventors could bring their inventions before the public – indeed, it encouraged them to do so by offering premiums for those deemed worthy of support. This was grist to the mill for a man such as Magellan, with his lively interest in novel technology. He attended the Society’s meetings and passed on details of inventions that particularly caught his eye to his correspondents abroad. He was elected a member of the Society on 2 May 1770 and a week later presented an invention of his own, an improved form of crane.37 He continued to be actively involved in the Society thereafter, for example proposing new members from time to time38 and serving as a referee on matters submitted to the Society.39

In the 1780s, Magellan was one of the three founding members of the less formal Coffee House Philosophical Society that took to meeting fortnightly except during the summer, usually at the Chapter coffee house near St Paul’s Cathedral in London and later at the Baptist’s Head coffee house in Chancery Lane, to discuss questions of natural philosophy. The moving spirit of the Society was the chemist Richard Kirwan, who usually presided at the meetings, and chemistry dominated its discussions; and the Society did not long survive Kirwan’s moving to Dublin in 1787. (The third founding member was Magellan’s friend Dr Adair Crawford.) Until the Society ceased functioning, Magellan attended meetings very regularly except when he was away from London and presided many times in Kirwan’s absence. Thanks to his international network of correspondents, he was well placed to bring forward items of scientific news that he had received from abroad. The growing challenge from Lavoisier and his colleagues to chemical theories based on the concept of phlogiston was a frequent topic for discussion. Kirwan was at this period one of the foremost critics of the new ideas emanating from Paris and Magellan, equally ← 14 | 15 → unpersuaded by Lavoisier’s ideas, diligently disseminated Kirwan’s arguments hither and yon.40

Details

- Pages

- 2002

- Publication Year

- 2017

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783034337151

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783034337212

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783034337229

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783034337236

- DOI

- 10.3726/b14851

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2019 (January)

- Published

- Bern, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, New York, Oxford, Warszawa, Wien, 2017. 2002 pp., 119 b/w ill., 1 coloured ill., 62 tables (2 vol.)

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG