Philology and Aesthetics

Figurative Masorah in Western European Manuscripts

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

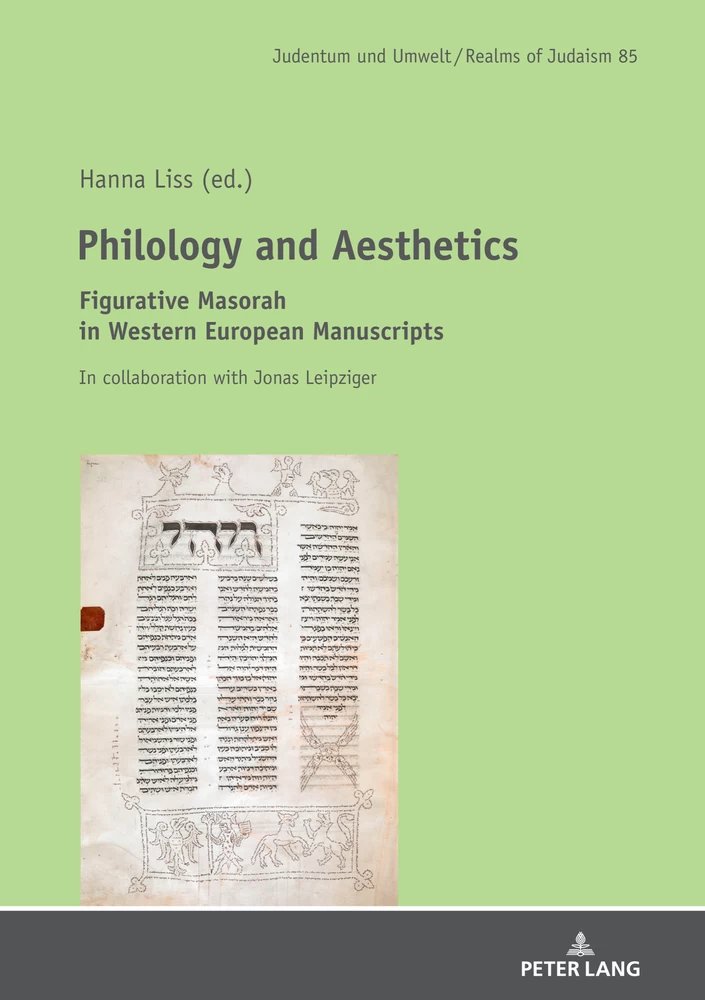

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Introduction: Editorial State of the Art of the Masoretic Corpus and Research Desiderata (Hanna Liss)

- Personal Grief Between Private and Public Space: A Micrographic Inscription as a Historical Source (MS Vienna Cod. hebr. 16) (Rainer Josef Barzen)

- Micrography Mounted Falconers: An Exegetic Text and Image (Dalia-Ruth Halperin)

- “How Am I Supposed to Read This?” Challenges and Opportunities of Medieval Western Masorah as a Digital Scholarly Edition (Clemens Liedtke)

- Masorah as Counter-Crusade? The Use of Masoretic List Material in MS London, British Library Or. 2091 (Hanna Liss)

- Illustrated Secret: Esoteric Traditions in the Micrography Decoration of Erfurt Bible 2 (SBB MS Or. Fol. 1212) (Sara Offenberg)

- Rashi in the Masorah: The Figurative Masorah in Ashkenazi Manuscripts as Parshanut (Kay Joe Petzold)

- The Interconnection Between Images and Texts. The Analysis of Four Masoretic Illustrations in MS Vat. ebr. 14 and Their Intertwined Relations (Hanna-Barbara Rost)

- The Okhla Lists in MS Berlin Or. Fol. 1213 (Erfurt 3) (Sebastian Seemann)

- List of Figures

- Notes on Contributors

- Indices

- 1 Manuscripts

- 2 Authors and Names

- 3 Hebrew Bible

- Series index

Hanna Liss

Heidelberg Center for Jewish Studies/Heidelberg University

Introduction: Editorial State of the Art of the Masoretic Corpus and Research Desiderata1

Abstract: This introduction deals with the history of research on the Biblical Masorah. It shows that at least from the 15th century onward, scholars have concentrated almost exclusively on the Masorah from the Oriental and – later – Sephardic manuscripts, and have completely neglected and even misjudged the philological, exegetical, and theological features of the Western European Masorah that often, though not always, appears as decorative ornaments in micrographic writing that has been given pictorial form, in keeping with the standard repertoire of Romanesque Bible illuminations, i.e. legendary creatures, chimeras, dragons or drolleries, or even anthropomorphic beings, similar to façade decorations or frescoes on and in church buildings.

Keywords: History of Masorah Research, Western European Bible Manuscripts, Art and Meaning of masora figurata

The term “Masorah,” as it is used in modern-day scientific research, refers to any kind of metatextual element apart from the consonantal text of the Hebrew Bible. It first appeared in comprehensive form in the great Oriental Bible codices, like the Codex Cairensis, 895 CE; Codex Babylonicus Petropolitanus (St. Petersburg, Russian National Library, Evr. I. B 3); the ←7 | 8→Aleppo Codex; and the Codex Leningradensis (St. Petersburg, Russian National Library, Evr. I. B 19a). The Masorah comprises mise-en-page and mise-en-texte, graphemes, grammatical, syntactic and statistical notes, as well as references and links, all of which are characteristic of not just Bible codices but also the Torah scrolls (sefer torah) used up to the present day for liturgical services at the synagogue. We distinguish between perpendicular Masorah on the side margins (the so-called masora parva – hereafter Mp) and horizontal Masorah on the lower and upper margins (masora magna – hereafter Mm) or at the very end of a book (masora finalis).2

1 The Masorah from the Middle Ages until the Wissenschaft des Judentums

The Masorah has come down to us via various artifacts and in different recensions. Complete Masoretic Bibles as well as isolated Masoretic lists have been in circulation since the ninth century (e.g. Okhla we-Okhla; Sefer ha-Ḥillufim). Since the eleventh century, these were continuously taken into account in the Spanish-Provençal and the Northern French-Ashkenazic Bible commentaries, as well as in Halakhic-liturgical works and in Hebrew-French glossaries. During this time, and under thus far historically undetermined circumstances, there emerged in medieval Ashkenaz (roughly, Germany and Northern France) a distinct Masoretic subversion of the Tiberian Masorah which deserves to be recognized as an independent textual type of Masorah due to its variant readings, its Masoretic idiosyncrasies, and especially its reception history. The Masoretic notations differ from the Oriental Masorah not only with respect to the philological content, but also in its layout and mise-en-texte as masora figurata. Starting in the thirteenth century, complete and partial Bibles appear in France and Germany in which the Masoretic list material, masora magna, and other list material are not only organized as linear masora magna or masora finalis, but appear in the form of decorative ornaments. In these cases, the Masorah is presented in micrographic writing that has been given pictorial ←8 | 9→form, in keeping with the standard repertoire of Romanesque Bible illuminations. It appears as legendary creatures, chimeras, dragons or drolleries, but also and especially as zoomorphic figures (dogs, horses, rabbits, gazelles, birds) and even as anthropomorphic beings, similar to façade decorations or frescoes on and in church buildings.3 In some instances, the Masorah was designed as diagrammatic representations, rendering scriptural constructs in geometric form (texts with a special visual structure). Manuscripts from the time leading up to the late thirteenth century demonstrate that this figurative Masorah (masora figurata), contrary to previous claims, did not necessarily lose any of its philological qualities by being presented in this form. Quite the opposite: Many lists that were relegated to the last pages in Oriental codices, often making them illegible and/or untraceable, are presented in toto on the folio pages of these works and are therefore easily accessible. Masora figurata also occasionally contains additional quotations from commentary literature and Midrashim that go far beyond the usual commentaries on the Biblical text, or even refer to different Bible commentaries, e.g. in MS Vat. ebr. 14.4

This parallel existence of conflicting Masoretic textual types continued for at least 200 years. However, starting in the middle or the end of the thirteenth century, after the blood libel accusation in Blois (1171) and the burning of a number of Talmud copies in Paris (1242) that dramatically diminished the corpora of Hebrew texts,5 the Jews of France were ←9 | 10→no longer able to pass on Northern French-Ashkenazic textual or commentary traditions without Oriental-Sephardic influence. Especially King Philip IV’s (1285–1315) order, in 1306, to expel the Jews from France led to the dissolution of substantial parts of Jewish communities and major waves of emigration.6 Likewise, the situation of the Ashkenazic communities in Germany deteriorated with great speed in the thirteenth century7 and reached a destructive climax with the so-called Rintfleisch massacres in 1298 and the Black Death-related Jewish persecutions of 1348/49. The Black Death persecutions, against which not even the voice of Pope Clemens VI could make itself heard, brought about the utter destruction of Ashkenazic culture on German soil: The great Jewish communities on the Rhine, among them Speyer, Worms, Mainz, Koblenz and Cologne, and thus the entire Rhenish-Ashkenazic scholarly tradition, were destroyed in August 1348/49.8 This catastrophe, at the very latest, led to a substantial and lasting decline of Ashkenazic scholarly culture.

The Ashkenazic Masoretic hypertexts lapsed into obscurity at the very latest when the first incunables were being printed. This can clearly be seen in the printed Biblical text and Masorah of Ya‘aqov ben Ḥayyim Ibn Adoniyah, in the so-called second Bomberg Bible of Venice of 1525 (Miqraot Gedolot; Bomberg2). Bomberg’s edition not only established the Biblical text as textus receptus for many years, but also reintegrated masora parva and masora magna in linear design, intended mainly for ←10 | 11→textual criticism.9 The fact that, after 1492, many printers stemmed from the Iberian peninsula and therefore brought with them a Sephardic manuscript tradition that was primarily linked to the Oriental tradition led to the successive displacement of Ashkenazic text and Masorah tradition. What’s more, figurative Masorah, being artistic in nature, didn’t easily lend itself to the copying process, whether in the manuscript tradition or in printing. The very uniqueness of this Masorah led to the difficulties that are apparent in the history of its reception. Even today, Masoretic lists written in straight lines are much more easy read than are intertwined circles whose beginning and end are not easy to find. The lack of reception of this philological-exegetical Masoretic tradition is especially unfortunate because the Jews of France and Germany, beginning no later than the twelfth century, set down many commentaries and annotations in the Bible codices in this way precisely in order to save their scholarly tradition from extinction. Unlike commentary literature, Hebrew Bibles were safe from willful destruction, even if they too had to withstand Christian censorship. However, as it turned out, by the time of the emergence of Christian Hebrew philology at the latest in the sixteenth century, only the oriental Masorah was still being passed on. It had found its way to Italy via Spain, was transmitted by way of the textus receptus, and was thereafter used as the definitive instrument for setting down the critical text. The artistic depictions of the Masorah faded out of focus, taking their exegetical and theological meaning with them.

With respect to the significance of the Oriental Bible codices and Masorah, one can already point to the critique of the European Masorah tradition by Eliyyahu ben Asher ha-Levi Ashkenazi (Elia Levita; 1469–1549), the author of the Masoret ha-Masoret, who criticized the figurative Masorah in these terms:

כי הסופרים הזידו, ועל המסורת לא הקפידו, רק עיקר חשיבותם, ליפות את כתיבתם, ולכוון את השורות, שלא ישנו את הצורות, ותהינה שוות בכל הדפין, ועוד אותן מיפין, בתמונות וציורים, בסכסוכים ובקישורים, ובציצים ובפרחים, ועל כן הם מוכרחים, לפעמים לקצר, ולפעמים לבצר, חומות הציורים, בדברים האמורים, במקומות אחרים, והם פה יתרים, ואין כאן מקומם, ולפעמים רשומם, במקום הראוי לא נכר, ולא זכרום כלל ועקר, כי המקום לא הספיק, והוצרכו להפסיק, באמצע הענין, ולא נשלם הבנין, והסורי מחסרים.

←11 | 12→For the Scribes have perverted them, as they did not care for the Massorah, but only thought to ornament their writing, and to make even lines so as not to alter the appearance, in order that all the pages should be alike. Moreover, they ornamented them with illuminations of divers kinds of buds, flowers, &c. Hence they were obliged sometimes to narrow and sometimes to widen the margins round the illustrations with words already stated, although they were superfluous and out of place, whilst the Massoretic signs were entirely omitted in their proper place because the space did not suffice; and hence they had to break off in the middle of a sentence, thus leaving the whole edifice incomplete and greatly defective.10

Finally, the fixation of the Masoretic tradition by Yedidyah Salomon Raphael ben Abraham Nortzi (1560–1626) in his Masoretic commentary Minḥat Shay,11 relying on the Sephardic Bible manuscript Cod. Parm. 2668 (de Rossi 782; Toledo 1277), led to the fact that from the humanist period onward, Biblical scholars established the priority of the Tiberian text type and its Masorah as well as the mythical authority of the Ben Asher school.

Since Protestant Biblical studies of the eighteenth and nineteenth century dedicated itself mainly to so-called higher criticism,12 only very few theologists (e.g. Hermann Hupfeld13) were interested in Masorah, and ←12 | 13→thus it was mainly Jewish scholars who devoted themselves to the task of editing the Masorah. In 1862, Adolf D. Neubauer14 published a short note on the discovery of an Okhla-recension in the Bibliothèque Impériale (today: Bibliothèque Nationale), that is today known as MS Paris BnF, hébr. 148, and was published by Salomon Frensdorff (1805–1880) in 1864 as Das Buch Ochlah W’ochlah (Massora).15 Whereas Frensdorff assumed one “original” Masorah-recension, Abraham Geiger, as early as 1854, had already observed that Masoretic notes in printed publications were flawed and unreliable. He insisted that one ought to reconstruct the Masorah not only on the basis of the variety of Bible manuscripts, but should also take the exegetical literature into account.16 Unlike his colleagues, Geiger was well aware of the dissimilar versions of Masoretic hypertext, especially regarding the differences between the Masorah of Oriental and Ashkenazic manuscripts.

One of the consequences of the exclusion of Jewish scholars from German universities in the nineteenth century was that the Masorah as a metatext to the Hebrew consonantal text became something of an academic orphan, since Protestant Biblical studies, focusing on archeology and ancient religious history and culture, mostly ignored medieval Hebrew-Aramaic hypertexts to the Biblical consonantal text. Even taking the works ←13 | 14→of Lazar Lipschütz,17 a Jewish student of Paul Kahle, into account, one has to acknowledge the fact that towards the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth century, critical work on the Masoretic Biblical text and on Masorah as an additional source of exegetical literature was, at least in Germany, utterly divorced from Old Testament Studies, and, as a corollary, from the Wissenschaft des Judentums. Jewish scholars simply didn’t have access to the universities and their resources, and academic biblical research took place almost exclusively within the framework of Protestant theology. This also explains why the early admonitions of Paul Kahle, the spiritus rector of Protestant Masorah research who, in 1913, presciently demanded an investigation of the European Masorah,18 were completely ignored.

2 Masorah Research in the Twentieth Century

For this reason, until today, only a small part of the Masorah has been critically edited and processed.19 Thus, the editions of the Okhla we-Okhla manuscript from Paris (BnF, hébr. 148)20 and of the masora magna by Frensdorff21 from the nineteenth century, as well as the editions from ←14 | 15→1975 and 1995 of the Okhla we-Okhla manuscript from Halle (MS Yb 4°10) by Fernando Díaz Esteban and Bruno Ognibeni,22 are still the basis for any work on the list Masorah. There is also the work of the convert Christian David Ginsburg, who published his magnum opus The Massorah Compiled from Manuscripts and his extensive Introduction to the Massoretico-Critical Edition of the Hebrew Bible between 1880 and 1885.23 When it comes to the Masorah corpora of Masoretic Bible codices, the masora parva of Codex St. Petersburg, Firkovich Evr. I B 19a “Codex Leningradensis” (1008), was edited and incorporated into the third Biblia Hebraica (BHK3)24 of Rudolph Kittel and Paul Kahle, and, in a second step, integrated in an enriched and normalized form into the Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia (BHS), together with the edited masora magna by Gérard E. Weil.25 In addition to modern-day Bible editions (BHS, BHQ, MQG Haketer, HUBP),26 the masora magna of Pentateuch MS Gottheil 14 (Breuer MS למ) has been published by Mordechai Breuer.27 In Madrid (CSIC), the Masorah of MS Madrid 1 (Toledo 1280) is being ←15 | 16→edited, including the Masoretic appendices.28 Aron Dotan and Nurit Reich compiled the Masorah of the Codex Leningradensis (Evr. I. B 19a).29 In 2013, David Marcus published the Aramaic mnemonics that appear in the masora magna of Evr. I B 19a.30 Recently, Yosef Ofer has started an edition project on the Masorah of MS S1 (formerly Sassoon 1053). Unfortunately, all of the listed editions of Masoretic material deal only with the Tiberian text tradition of the Ben Asher school,31 and only a few of the editions published so far are available in digital form.

3 Research on the Ashkenazic Masoretic Tradition

At present, only very few scholars – among them those presenting their research in this volume – are working on the edition of the European Masorah. The (Western) European Bible manuscripts and their Masorah traditions, which also include list material on a large scale, have so far been almost completely disregarded within the framework of text-critical research dealing with the Bible text and with the Masorah. This means that a very substantial text corpus has been philologically and editorially neglected. This corpus includes approximately 76 dated and undated Ashkenazic Bible manuscripts (complete or partial) from the time period ←16 | 17→between 1189 (MS Valmadonna Trust 1; Washington, Museum of the Bible, CG. MS. 000858; former: Sassoon 282) and the end of the thirteenth century, containing, in addition to the Biblical text and to varying degrees, the Targum (separate or interlinear), the Masorah, commentaries, Masoretic micrographs, as well as other specific text elements (e.g. tagin). These European (Ashkenazic) Bible codices remain overlooked today. Until very recently, they have never been appreciated, neither as a constitutive element of the Biblical text nor as a source of the Jewish (and Christian) medieval European literary and exegetic history of their Masoretic hypertext.32 Approaching the issue from a different angle, the Judaic art-historical works dealing with micrographs in Bible and Haggadah manuscripts have so far never included philological considerations of the micrographically shaped masora figurata, but have dealt almost exclusively with artistic and historical aspects, although Dalia-Ruth Halperin did already demand a “precise reading of the micrography,”33 with regard to the Catalan Mahzor, in 2013.

←17 | 18→Investigating this original Ashkenazic Masoretic tradition is of the utmost importance, since research on Occidental Biblical text traditions and Jewish commentary literature in Medieval Western Europe cannot properly be addressed by using Oriental manuscripts and Masorah tradition instead of the Bible manuscripts of Western Europe. We see nowadays that the variation-rich textualization of the Masorah most notably depended on, and was integrated into, its socio-cultural context. Precisely for this reason, the thus far ignored Ashkenazic Masorah tradition – as opposed to the Tiberian – constitutes a central component of the cultural inheritance of both the Jewish and the Christian Middle Ages and deserves to be illuminated in future studies. The Hebrew-Aramaic commentaries on the Bible and Talmud, as well as the Masoretic references in the Halakhic compilation literature by the Northern French school of exegetes and Tosafists (Rashi; Rabbeinu Tam; R. Menaḥem of Joigny; R. Yitzḥak of Evreux), but also the Latin exegesis (dependent on, and characterized by conflict with, Jewish scholars)34 deserve to be evaluated to a much greater degree than has previously been the case against the backdrop of the Western European text and Masorah tradition. Furthermore, the acquisition of the Ashkenazic Masorah will offer significant starting points for future research in the field of medieval Hebrew-Aramaic linguistics, since both the Aramaisms in the Hebrew language and the purely Aramaic ←18 | 19→hypertexts in the masora magna and figurata in these manuscripts have not been investigated so far. Researchers of the history of the Biblical text will also want to include a viewpoint of the so-called (Masoretic) “reception history” of the Biblical text as a “text history” (a position shared in recent research on the Quran35). These aspects constitute important connection points with Jewish and Christian theology and medieval art history and have implications far beyond Judaic medieval studies.

Initial philological investigations on the European Masorah have been undertaken by Élodie Attia,36 Hanna Liss,37 and Kay Joe Petzold38 within the framework of the Collaborative Research Center 933 (Material Text Cultures) of the University of Heidelberg and the Heidelberg Center for ←19 | 20→Jewish Studies, starting in 2011.39 Attia’s results, compiled into a partial edition of masora figurata compositions in MS Vatican ebr. 14,40 showed that, beyond the strong influences from Tiberian sources, an additional strand of substantial non-conventional Ashkenazic Masoretic tradition was utilized by the masran Eliyya ben Berekhya ha-Naqdan.

Complementary to Attia’s work, Liss and Petzold set out to investigate the Masoretic transmissions and meta-commentaries to the Masorah in Hebrew Bible commentaries of the High Middle Ages from the area of Northern France and Ashkenaz, especially those of R. Shlomo Yitzḥaki (Rashi; ca. 1040–1105), R. Abraham Ibn Ezra (ca. 1090–ca. 1165), R. Yehudah he-Ḥasid (ca. 1150–1217), R. El’azar ben Yehudah of Worms (1165–1230), R. Yosef Kimḥi (ca. 1105–ca. 70), R. Moshe Kimḥi (d. ca. 1190), R. David Kimḥi (1160–1235), R. Meïr ben Barukh of Rothenburg (MaHaRaM; ca. 1220–93) or R. Ya‘akov ben Asher (Ba‘al ha-Ṭurim; ca. 1269–ca. 1343).41 The commentators refer either to independent Masoretic compilations like the Sefer ha-Masoret (“the book of the Masorah”) or to the Masoret ha-Gedolah (“the great Masorah”), respectively; sometimes reference is made simply to “the Masorah” (ha-Masoret; probably notations within the Bible codices) or to works of the so-called ba‘ale/anshe ha-masoret (“men of the Masorah”). This extensive material has so far been dealt with only rather sparsely and eclectically,42 and was investigated systematically for the first time in Petzold’s dissertation dealing with the Masoretic material in the various manuscripts of Rashi’s commentaries.43 Petzold primarily set out to establish which recension(s) ←20 | 21→of the Hebrew Bible and which outside material, i.e. Masoretic material compiled in other works besides Biblical codices, Rashi used, as well as how this material relates to that of the Tiberian ben Asher tradition. He succeeded in showing that a lot of this outside material, among them an Okhla we-Okhla recension that Rashi used, came into existence only in the eleventh century. Petzold was able to demonstrate that a successive “contamination” of Ashkenazic texts with the Ben Asherian Masorah took place in the twelfth and early thirteenth centuries (MSS BM Harley 5710; München 2; BM Add. 15451; Wrocław 1106; München 392; and Jerusalem IM 180_52, “Regensburg Pentateuch”).44 This led to numerous complications, since the intrusion of Tiberian Masorah derived from the Oriental codices caused problems not only with plene and defective writing, but with accentuation and numerous variant readings of the consonantal text. This was relevant not only to Halakhic interpretations of the Biblical text, but also for the writing of Torah scrolls for liturgical use, and led to various disputes and a wide range of contemporary responsa literature (Shlomo ben Adret).45

4 Art and Meaning of the masora figurata

From 2016 onwards, Clemens Liedtke, Hanna Liss, and Kay Joe Petzold started working on a digital edition of the complete masora figurata in Vat. ebr. 14 (written in 1239 in Rouen).46 Within that framework, Attia’s findings for Exodus are being supplemented and revised, and the editorial work has been extended to the entire Pentateuch. Now, and within the framework of a detailed analysis of the iconographic program of the manuscript’s masora figurata, substantial results have been achieved with regard to the text-image relationship of the masora figurata in this manuscript. It can be shown that the copyist (sofer/naqdan/masran), Eliyya ben Berekhya ha-Naqdan, who lived in Rouen in Normandy, integrated iconic ←21 | 22→hints on exegetical commentaries and halakhic discourses into each and every figurative Masorah. Whether the decorative and attractive creation of such a book was made to appeal to a broader audience, like uneducated men, children, or women, or whether the figurative images were designed to transfer philological discourses from a purely scholarly culture into the broader realms of Jewish culture, is the central issue to be discussed. To arrive at a clearer result, Liss and Petzold integrated praxeological methods and praxeologically oriented analyses of the artifacts, techniques that were developed at the CRC 933 at Heidelberg.47

In her work The Transformative Power of Performance: A New Aesthetics, Erika Fischer-Lichte discusses the question of how the material and the symbolic stand in relation to one another.48 She insists on the fact that every deliberate act of awareness generates meanings which are not to be equated with a purely linguistic meaning. With regard to the Masoretic images, one might say that every micrographic figure of a dragon, an eagle, or an ox in its own way presents something eye-catching, which is likely to trigger one (or more) attribution(s) of meaning, both in that which is created by the masora figurata and in those who observe it. However, this meaning arises either on the micrographically processed basis of the Hebrew text (Masorah) or from its external form (design); in other words, is there a reason why mythical animals (dragons) or clearly unclean animals (dogs, rabbits/hares) are often depicted in decorative micrography, or is the decoration purely arbitrary? At the same time, it should be kept in mind that the contexts of meaning of materiality are also obtained on a “meta” level, that is to say above and beyond the pure relationship between the text and the image.

Applying Fischer-Lichte’s approach to the masora figurata images, the following questions should be posed:

– Of what kind is the “Masorah” on a given folio?

– Is the Masoretic material complete or incomplete? Is there a beginning and an end?

– What is the relationship between this material and Masoretic list material as we find it in independent Masoretic treatises (like Okhla we-Okhla)?

– Is the Masoretic material placed in situ, i.e. do we find corresponding masora parva and masora magna material on the same folio?

– What is the relationship between the iconographic program and the philological material? Is there any relationship between the text and the image?

– What can we say about the order of the formation of the figuratae? Did the scribe sketch the image first and then choose Masoretic material matching the size of the image, or did he design the masora figurata according to the material to be arranged, i.e. the quantity of words or letters needed?

– What and how can we find out about the scribe’s reason for arranging Masoretic material in this way?

In addressing these issues, research on masora figurata will reach a new stage of development, combining art-historical and philological questions.

5 The Present Volume

This volume collects research on the Western European Masorah, in particular on masora figurata, and addresses the question of why Ashkenazic scholars tried to integrate the Oriental Masoretic tradition that was originally developed as linguistic-grammatical knowledge vis-à-vis Islamic punditry into Western European Rabbinic lore and law. This inculturation took place in and was conceivably influenced by the Christian environment (theology; iconography; book illumination; architecture). The articles will not merely address hitherto well-known philological and art-historical questions, but will develop a tableau of methodological tools for the analysis of masora figurata within the larger theoretical framework of material text cultures.49 The research presented here is based on papers ←23 | 24→that were given at the Seventeenth World Congress of Jewish Studies (Jerusalem 2017), as well as at the workshop Philology and Aesthetics (Heidelberg Center for Jewish Studies) in May 2018. This workshop, in which Bible philologists and art historians were brought together, initiated a most fruitful conversion, in which one side learned a lot as regards the variety of turreted tower gates, head coverings, hunt scenes, etc., whereas the other side was introduced to Masoretic studies as well as to editorial techniques for dealing with the micrographic images. Thus, all papers in one way or another deal with Masoretic material derived from Ashkenazic Bible manuscripts.

Details

- Pages

- 290

- Publication Year

- 2021

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783631829530

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783631858103

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783631858110

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783631858127

- DOI

- 10.3726/b18566

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2021 (June)

- Keywords

- Digital Edition Micrography Ashkenazic Bibles Ashkenazic and Oriental Masorah

- Published

- Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Warszawa, Wien, 2021. 290 pp., 12 fig. col., 37 fig. b/w.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG