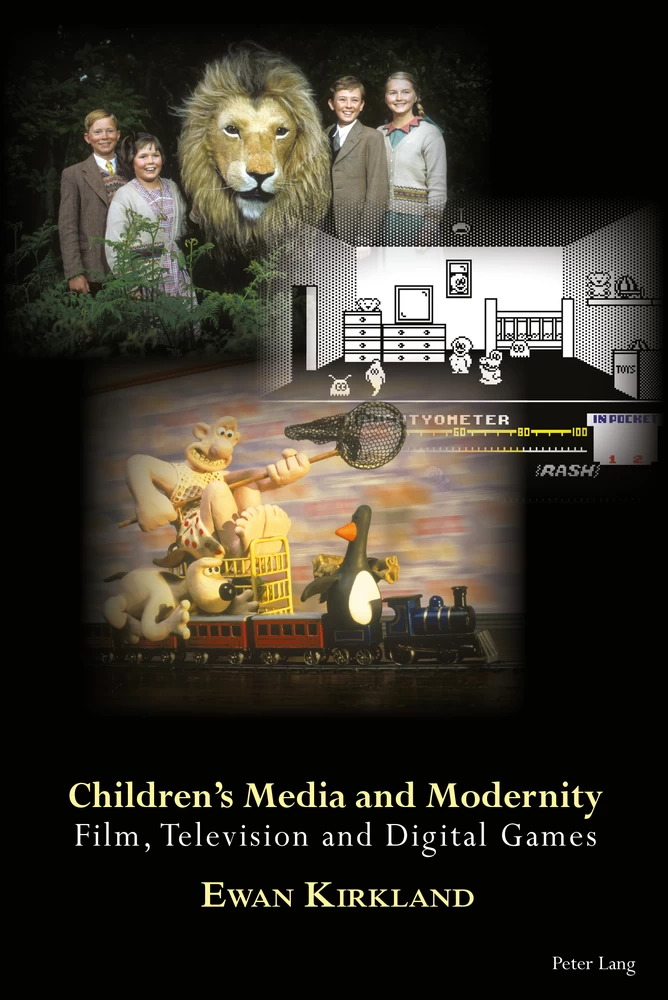

Children’s Media and Modernity

Film, Television and Digital Games

Summary

This book explores how products for children navigate such contradictions by investigating the history and textuality of three major forms of modern media: cinema, television and digital games. Case studies – including Wallace and Gromit, Teletubbies, Horrible Histories, Little Big Planet and Disney Infinity – are used to illustrate the complex intersections between children’s culture and modernity.

Cinema – so closely associated with the emergence of modernity and mass popular culture – has had to negotiate its relationship with child audiences and depictions of childhood, often concealing its connection with modernity in the process. In contrast, television’s incorporation into family home-centred, post-war modernity resulted in children being clearly positioned as the audience for this domestic entertainment. The latter decades of the twentieth century saw the promotion of home computers as educational tools for training future generations, capitalising on positive alignments between children and technologies, while digital games’ narrative references, aesthetics and merchandise established the new medium as a form of children’s culture.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Chapter 1: Thinking of the Children

- Chapter 2: History, Childhood and Modernity

- Chapter 3: Cinema for Children

- Chapter 4: Television for Children

- Chapter 5: Digital Games for Children

- Chapter 6: Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

Childhood, Time and Modernity

For all adults – including writers, producers, consumers and academics of media for children – childhood is largely located in the past. Even for those with children in their lives, the most intimate encounter with childhood an adult is likely to have is with their own. This retrospective experience of being a child is bound to be characterised by elements of uncertainty, ambiguity, fictionality. Adult childhood is a complex reconstruction based on clearly recalled events, false or uncertain memories, mementoes in the form of photographs and other surviving childhood relics, books, toys and games. It is a childhood depicted in black and white or faded colours. It is populated by people with strange haircuts, clad in unfashionable clothing. It is represented by stories, activities and culture which, from the vantage of the present, appear at best quaint, outdated, superseded, at worst unenlightened, ideologically incorrect and insensitive. In our childhood, be it real or imagined, there were fewer cars on the road, fewer consumer goods in the shops, less bureaucracy regulating our actions. When it comes to media, films were more rudimentary in their special and visual effects. Television shows were less slick and glossy. Computers and telephones were larger and less portable. The internet, if it existed at all, was slower, its content less expansive and multi-media. Videogames were more simplistic in their graphics and gameplay. Being an adult often involves coming to terms with media technologies and culture which was not a feature of our own early years. When looked upon with fond adult nostalgia, childhood is a period which appears less technological, less sophisticated, less complex, in many ways, in the colloquial sense of the term, less modern. Without rose-tinted ← 1 | 2 → glasses, childhood can conversely feel like a place of darkness, of limited freedoms and opportunities, of social and cultural exclusion enforced by a ruling adult elite. Also in many ways, less modern.

A central argument of this volume is that a productive way of understanding childhood, and the many complex and contradictory elements this concept evokes, is through ideas of modernity. The contemporary Western child appears to be a distinctly modern invention. Many significant and enduring perspectives on the difference between adults and children, now taken for granted, emerged alongside modern developments within the Western world. Contemporary childhood was forged in the heat of modernity. In such a context the imaginary figure of the child comes to embody many contradictions, anxieties and hopes of the very era which brought it into being. Childhood serves as a receptacle for everything adults feel they have left behind in the maturation from what is believed to be simpler, more natural, more innocent ways of being. The child functions to articulate adult dislocation from modernity, and anxiety about the speed of social, cultural and technological change. Media for children, including books, films, television and digital games, themselves a product of cultural modernity and modern methods of reproduction, can be understood as a site where these tensions are expressed, negotiated and symbolically reconciled.

Of course, this is not the only meaning attached to childhood. In some formations childhood is not located in the past, but in the future. The children of today represent the adults of tomorrow, the generation which will live on after we are long gone. This constitutes a significantly more optimistic perspective on children and modernity, wherein childhood becomes a site of hope and anticipation rather than nostalgia and loss. Such a conception of childhood can also serve to critique current circumstances, highlighting the inequalities, injustices and indignities of the present, in contrast with some utopian point in the future, rather than an idealised past. That childhood can serve such seemingly incompatible functions, indicates the complex mythic qualities of the concept. Childhood is not a singular formation, but the site of competing perspectives and interpretations. Throughout Western history there have been many conflicting conceptions of what childhood is and what children are, deriving ← 2 | 3 → from theological, philosophical, scientific fields and disciplines. Some of these appear in distinct opposition. Images of childhood innocence seem to contradict concepts of the child as full of sin and in need of control. Ideas of childhood as a time of triviality and carefree activity, coexists with assertions that childhood is the most important formative years of an individual’s life. The notion of childhood as a period of play seems at odds with an emphasis on the importance of education and productive activity. Mythologies of childhood as the best time of your life jostle with narratives of childhood as a state of helplessness, confusion and exploitation. The most successful cultural articulations of childhood express multiple conceptions, or better still, manage to stabilise such contrasting beliefs in a seemingly unified whole.

Whether childhood is situated in an imaginary past or an imaginary future, modernity seems to function as a recurring theme. In many respects the ambivalences of childhood reflect the uncertainties of modernity itself, just as childhood evades modernity’s efforts to fix and determine its boundaries. This study involves bringing together these two complex, contradictory concepts. Media for children assumes three broad and frequently overlapping approaches. The most common and easily identified of these entails a retreat into a previous era, reflecting a childhood which stands outside of modernity. This frequently assumes a kind of ‘neo-medievalism’ as exemplified by numerous folktale-inspired animated films, fairy story television shows and videogames featuring captured princesses, beanstalks and trap-filled dungeons. In such circumstances the implied child consumer is effectively relocated to a fantastical realm safe from the trappings of modern life. Another strategy across children’s media attempts a reconciliation between modernity and the child, acknowledging the problematic relationship between the two in trying to overcome it. Images of chocolate factories powered by waterfall, inventors constructing elaborate machines from domestic objects, television cyborg aliens inhabiting pastoral landscapes, all represent instances of this tendency. A third form of children’s culture embraces modernity in all its frenetic ambivalence, reflecting a childhood which is conceived of as the very embodiment of the modern era. Notably many new techniques in screen entertainment are trialled in media for children, and many new media technologies are promoted ← 3 | 4 → as being beneficial for young people. This suggests that child consumers have a particular appreciation of the technological innovation with which modernity is associated. Most examples of children’s media constitute a combination of these three positions.

At this early stage it is useful to make clear the boundaries and limitations of this publication. This is not a study of children and media. Its focus is rather the historical, cultural and institutional ways in which young people have been engaged as an audience, and aspect of children’s culture translated across different media formats. The critical perspective this study adopts, inspired by Gill Branston’s study of cinema,1 interrogates the relationship between childhood and modernity, as articulated through media produced for, made available to, or variously marketed towards children. Such an approach draws together the work of many historians, media scholars and critics of childhood who have observed, in various ways, children and childhood’s problematic relationship with the qualities that define the modern condition. Through focusing on childhood in children’s culture, other important identity formations, such as gender, race, ethnicity, nationality or class, are given comparatively little attention. This is not to diminish the significance of these categories, the many ways in which they inform the further segmentation of children’s culture, or the extent to which childhood as a stable identity fragments upon acknowledgement that children, no less than adults, are divided along these lines. The emphasis on childhood is rather intended to address the degree to which this identity is often taken for granted, rather than subjected to the critical interrogation commonly applied to other classifications, even in discussion of media for children. In addition this study is undeniably Western, in terms of the childhood it explores and the media it analyses. The intention is not to universalise this specific conception of childhood which, as the following overview makes apparent, is not only historically particular but also geographically, nationally and regionally specific. It may well be that a study of the childhoods of non-Western cultures, and the media produced to meet these children, would result in significantly different findings and conclusions. ← 4 | 5 → The concentration on modernity has also resulted in the study’s emphasis on screen media. Consequently other forms of children’s culture, such as books, comics, magazines, toys and board games, are necessarily excluded. Scholars of children’s literature are admittedly a frequent source of reference, the study of books for children being a more established field than other media for young people. Further examples, including clothing, food, games and action figures, are also considered as contributing to the ways in which children’s screen media is oriented towards child audiences through ancillary products. It would undoubtedly be fruitful for subsequent research to consider the ways in which books, sequential art, periodicals and non-digital games for children might be similarly explored as reflecting upon childhood, modernity and media.

As such this is not a study of the role media plays in children’s lives, the meanings children make of media, or the nature of children’s engagement with popular culture, although many valuable contributions to this area of research are cited in the following chapters. Much work on the history of children’s matinees draws upon adults’ recollections of cinema-going, the films they saw, and the experience of being in the auditorium. These insights are valuable in determining the content of early screenings which were not recorded at the time. Evidence of children’s, and adults’, television viewing preferences will inform definitions of children’s programmes as those favoured by child audiences, alongside issues of scheduling, production and merchandising. Studies of adults’ engagement with cinema and digital games consoles, expressing perceptions of cinema as an adult-only space, and videogame play as a distinctly childish activity, provide useful perspectives on these respective media, and constitute insightful postscripts to their respective chapters. However, this study makes no original contributions to empirical or ethnographic research. Indeed, the critical perspective this study adopts in relation to the child as a product of historical forces entails a sceptical approach towards any universalising claims concerning experiences, tastes, practices or affinities determined by age-based categories of audience. This does not invalidate the findings of such research, and it must be acknowledged that the majority of studies cited do have a critical awareness of the problems of such endeavours. However, this study retains ← 5 | 6 → focus on children’s media, its production, distribution, exhibition, rather than the children, and adults, who consume it.

The Meanings of Childhood

Underpinning this study is an understanding that childhood as a concept has been primarily historically, socially and culturally determined. Histories of childhood, as detailed in the next chapter, although subject to considerable dispute, tell a story in which the meaning of childhood appears to have undergone significant transformation over recent centuries. Cross-cultural studies also reveal significant variation in the ways childhood is understood across different national contexts. This absence of consistency suggests that concepts of childhood, including beliefs circulating what a child is, needs, wants, deserves, and the crucial ways in which children differ from adults, are a matter of cultural convention rather than ontological inevitability. In this respect agehood, meaning childhood, adulthood and all the variations between, before and after, can be considered a social construction similar to gender, race, class, sexuality, ability and so forth. Despite parallels between children and other historically marginal groups, and evidence suggesting childhood is a socially determined identity, until relatively recently, and then only in certain quarters, childhood has not been recognised as a minority status, or as a formation which has been culturally, historically, discursively produced.

Consistent with other marginalised formations, childhood is not simply a social category, but once with significant symbolic meaning. As Marilyn R. Brown writes, in the introduction to an edited collection on images of children in portraiture, ‘childhood has been primarily a cultural invention and a site of emotional projection by adults’.2 Along similar lines ← 6 | 7 → John R. Gillis writes of the ‘virtual child’, an invention of the Victorian era, a symbolic rather than actual figure. For Gillis it was the nineteenth century when contemporary ideas of childhood become hegemonic within middle-class Anglo-American cultures, being increasingly embedded and naturalised within emerging structures of class and gender.3 Literary critic Marina Warner also points to the mythical functions children serve for adult dreams and desires. The author uses the term ‘supernatural irrationality’ to define the various concepts of imagination, fantasy, wisdom, innocence and sexlessness facilitated by the figure of the child.4 Symbolic meanings invested in childhood, as Gillis suggests, effectively obscure the ‘real’ child from view. Indeed, Dennis Denisoff argues that it is an impossible task to disentangle the actual child from social construction of childhood.5 A similar point is made by Carolyn Steedman in distinguishing ‘real children, living in the time and space of particular societies’ from ‘the ideational and figurative force of their existence’.6 Historical accounts reveal the two as having a reciprocal relationship. Emerging ideas of childhood in the late eighteenth and early ninetieth centuries, which Steedman argues functioned as a means of adults negotiating contemporary ideas of self and history, impacted on the attention paid to actual children throughout this period and consequently upon the lives of children themselves. Adult culture determines children’s lives according to beliefs in what children are, and children to varying degrees are impacted and transformed by the resulting institutions within which they are located.

As previously suggested, childhood is not a singular category, but multiple. Throughout history ‘the child’ has been employed for different ← 7 | 8 → ends by a range of political, cultural, artistic movements. Indicative of the extreme malleability of the virtual child, Brown identifies further paradoxes of childhood within nineteenth-century Europe. During this period, the industrial exploitation of children was accompanied by the cultural glorification and sentimentalisation of childhood within Victorian society. The nostalgic celebration of the child entailed a symbolic withdrawal from urban industrialisation, and the political and scientific revolutions of the era. Yet this was concurrent with the development of a considerable industry organised around the mass production of children’s toys, clothes, books and child-rearing manuals, mobilising children as emblems of social, cultural and economic progress.7 The extent to which children become symbols for adult society suggests the power inequalities between the generations. Although children are themselves not without agency, it is largely adults who have the authority to define childhood in this symbolic sense. As historian Hugh Cunningham observes, ‘mostly what we hear are adults imagining childhood, inventing it, in order to make sense of their world. Children have to live with the consequences’.8 Exploring the political nature of childhood is nevertheless inhibited by the absence of a readily available language which might allow such inequalities to be effectively articulated. George Dimock makes speculative parallels between the exclusion of art by children from the cannon of art history and the exclusion of women artists. The author observes that while art history and cultural studies have incorporated children and childhood into the analysis of representation, this is not situated within a clear critical framework. There is no established discourse of ‘adultism’, or adult privilege, comparable to the interventions made in challenging the depiction and agency of other minority groups.9 Nevertheless any critical engagement with ideas of childhood, children and children’s media cannot avoid addressing the politics of this situation. ← 8 | 9 →

Throughout history children and childhood have therefore been made to bear an array of meanings. Most of these processes take some innate or biological aspect of children and extrapolate this to advance a particular argument or claim. It seems indisputable that most children are smaller and less strong than most adults. This leads to the proposition that children are in need of protection, even from threats that are more psychological or ideological than physical. Steedman is amongst many to note discourses of ‘littleness’ constantly circulating the child. In researching a cultural history of childhood, the author observes a point where ‘it seemed to me that what I was really describing was littleness itself, and the complex register of affect that has been invested in the word “little”’.10 In such a situation the biologically rooted meanings circulating children, rather than children themselves, emerge as the more truthful subject of the discourse under analysis. The notion of littleness is evident in children’s media, from the earliest publication for children to the latest digital games. Another recurring concept is that of childhood innocence. This is perhaps the most persistent symbolic quality attributed to children, one which Cunningham observes even in the later stages of the Middle Ages.11 It is hard to dispute that generally speaking children have less experience than adults, having lived shorter lives, and are consequently less knowledgeable, having had limited time to gain awareness of the world. But to define this comparative lack as a form of ‘innocence’ involves imposing an interpretation of such qualities that is highly valued, selective and cultural. While the question of child sexuality is a matter of heated dispute, it does appear that before the onset of puberty children have a different relationship with sex, their own bodies, and the bodies of others, compared to those who have passed this biological threshold. However, to interpret this ‘difference’ as asexuality, the absence of sexual desire, or as a vulnerability to sexuality, sexual imagery, information or activity, is a cultural position which impacts significantly on the lives of children and the media made available to them. This perception of innocence is clearly articulated in the regulations determining the classification of films and other screen texts, where titles containing ← 9 | 10 → material of a sexual nature are prohibitively certificated to exclude young people from viewing or purchasing such media. The strong desire to maintain childhood innocence, rather than to introduce children to concepts of sexuality and sexual relations, arguably says as much about Western attitudes towards sex as it does about childhood. Moreover the sheltering of children from sexuality might contribute to producing the very ‘innocence’ such practices claim to recognise.

Recent debates surrounding children’s exposure to internet pornography, concerns about childhood obesity, or arguments for the prohibition of advertising targeted at children, reflect ambivalence about sexuality, new media, public health, consumption, commercialism and promotional culture. In such situations, concern for children might be seen as secondary to the anxieties the child permits to be articulated. As a highly mobile symbolic receptacle for a range of values, which also exists as people in the ‘real’ world, the child constructed through journalistic narratives, statistics, government reports or academic papers, might be produced at any moment as a reification of the subject under debate. The clichéd rally cry, ‘won’t somebody think of the children’ carries with it considerable currency, irrespective of the cause to which it is attached. Children’s smallness, their lack of experience, their different relationship with sexuality, all located in biological aspects of children, feed perceptions of childhood vulnerability which can be mobilised by campaigners across the political and ideological spectrum. Such concepts of childhood, informing debates relating to children’s access to mainstream media and culture, invariably impact on the design of media and culture specifically aimed at children themselves.

The Problem of the Child in Media for Children

In a substantial passage, raising various rhetorical questions as pertinent to children’s film, television and digital games as they are to children’s books, Peter Hunt highlights the problem of defining children’s media in a section worth quoting at length: ← 10 | 11 →

Children’s literature seems at first sight to be a simple idea: books written for children, books read by children. But in theory and in practice it is vastly more complicated than that. Just to unpack that definition: what does written for mean? Surely the intention of the author is not a very reliable guide, not to mention the intention of the publisher – or even the format of the book? For example, Jill Murphy’s highly successful series of picture-books about the domestic affairs of a family of elephants … are jokes almost entirely from the point of view of (and largely understandable only by) parents. Then again, read by: surely sometime, somewhere, all books have been read by one child or another? And some much-vaunted books for children are either not read by them, or much more appreciated by adults (like Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland), or probably not children’s books at all (like The Wind in the Willows), or seem to serve adults and children in different – and perhaps opposing – ways (like Winnie-the-Pooh). And do we mean read by voluntarily or, as it were, under duress in the classroom? And can we say that a child can really read, in the sense of realizing the same spectrum of meanings as the adult can?12

Hunt’s questions might well be expanded and reoriented to cover issues within media studies. What is implied in labelling a piece of media ‘children’s’? What potential relationship between child and media might be entailed in the term? What kind of child is implicated in this process? What age, what historical period, what formation of audience? Does calling a piece of media ‘children’s’ necessarily imply that a significant portion of children have encountered it, enjoyed it, incorporated it into their culture, and continue to do so? Does it imply that it has been made for, marketed at, targeted towards children, and has been successful in its endeavours to reach this audience? Is children’s media a matter of genre, suggesting a group of texts which share characteristics with others labelled in the same way? Is children’s media a matter of consumption, production or textuality? Is a piece of media which has been made for adults but which finds favour with child audiences children’s media? Conversely, if something is produced with children in mind, but gains an adult following, with endorsement from its creators, should it no longer be defined by the term? Is children’s media an institution which transcends the tastes of child consumers? Is it ← 11 | 12 → instead defined by academics, archivists, distributors, exhibitors, television stations, certification bodies and pedagogues?

Details

- Pages

- VIII, 296

- Publication Year

- 2017

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781787074101

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781787074118

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781787074125

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783034319911

- DOI

- 10.3726/b10952

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2017 (July)

- Keywords

- children media modernity film television digital games

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, New York, Wien, 2017. VIII, 296 pp.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG