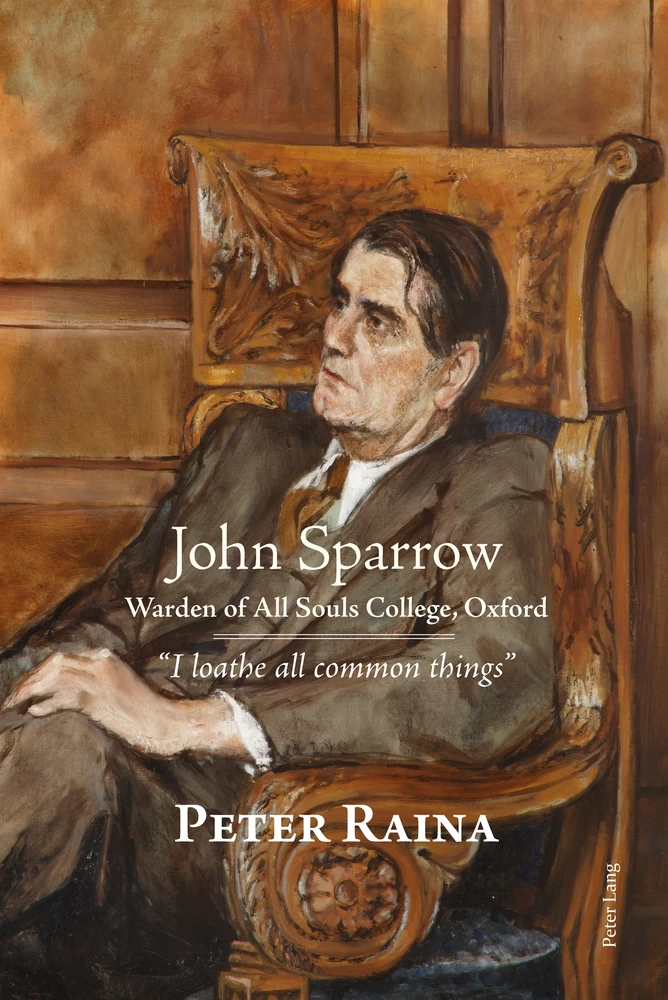

John Sparrow: Warden of All Souls College, Oxford

«I loathe all common things»

Summary

Presenting hitherto unpublished letters and papers which vividly evoke the contemporary Oxford scene, Peter Raina traces this scattering of talent. Sparrow may have been a generalist, but he dabbled in depth in many disciplines. He was an expert on Latin, on law, on inscriptions, on rare books and on poetry. Above all he was a tireless supporter and friend of other academics and poets in a special generation. The book gives context to his circles of influence and to his uncompromising intelligence and distinct charm.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter 1: Margaret Sparrow: The Mother

- Chapter 2: Mother’s Darling

- Chapter 3: The Prep School: Childhood Passions

- Chapter 4: Winchester College

- Chapter 5: John Sparrow at Winchester College

- Chapter 6: A Passion for Debating and Poetry

- Annex 1: A Trusted Wykehamist

- Chapter 7: “Oxford Must Begin Some Time”

- Chapter 8: “I Do Not Want Ever to Go Near a Jury”

- Chapter 9: “I Had No Desire for a Commission”

- Chapter 10: “It is the Thing I Want and Always Have Wanted”

- Annex 2: Sparrow’s Commemoration of Cyril Radcliffe

- Chapter 11: A Self-Fulfilling Job

- Chapter 12: Private Affairs: Homosexuality

- Annex 3: John Sparrow’s Memorial Address for Harold Nicolson

- Chapter 13: University and College

- Chapter 14: “What Mellors Did Was Unconventional and Even Perverse”

- Chapter 15: Keep Your Friendship “in Constant Repair”

- Chapter 16: Passion for Controversy

- Chapter 17: “My Dear Master”

- Chapter 18: “Shielding the Conservative Establishment”

- Annex 4: Atticus’ “Sparrow and the Hawks”, The Sunday Times, 24 November 1968

- Annex 5: Document on University Freedom

- Chapter 19: Letter-Writing with Ease

- Chapter 20: “I Had Decided Not to be Disappointed if I Wasn’t Elected”

- Chapter 21: “Here, with his Talents in a Napkin Hid, Lies One who Much Designed, and Nothing Did”

- Chapter 22: John Sparrow’s “Words on the Air”

- Chapter 23: Death

- Chapter 24: Epilogue

- Bibliography

- Index

- Series index

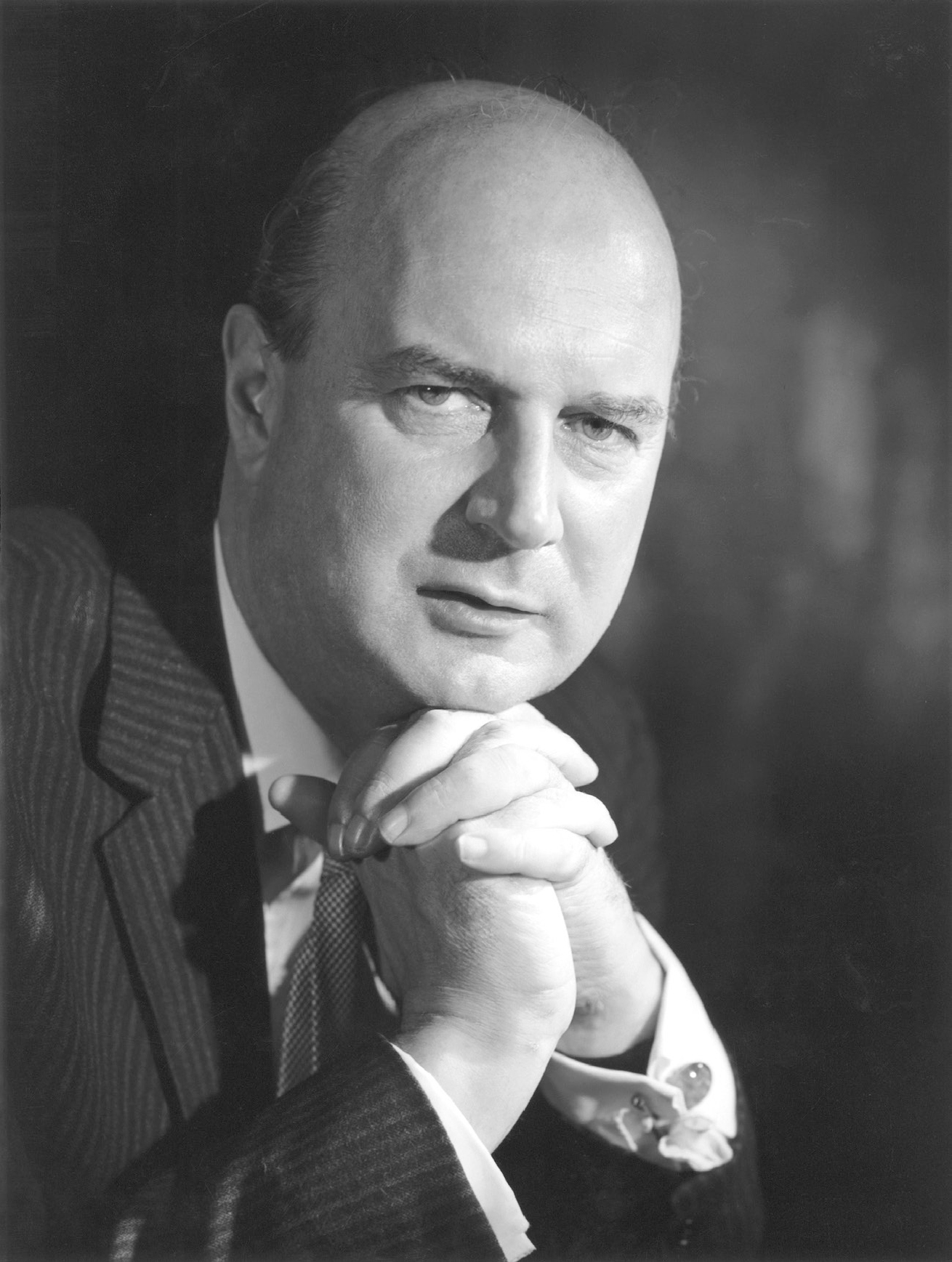

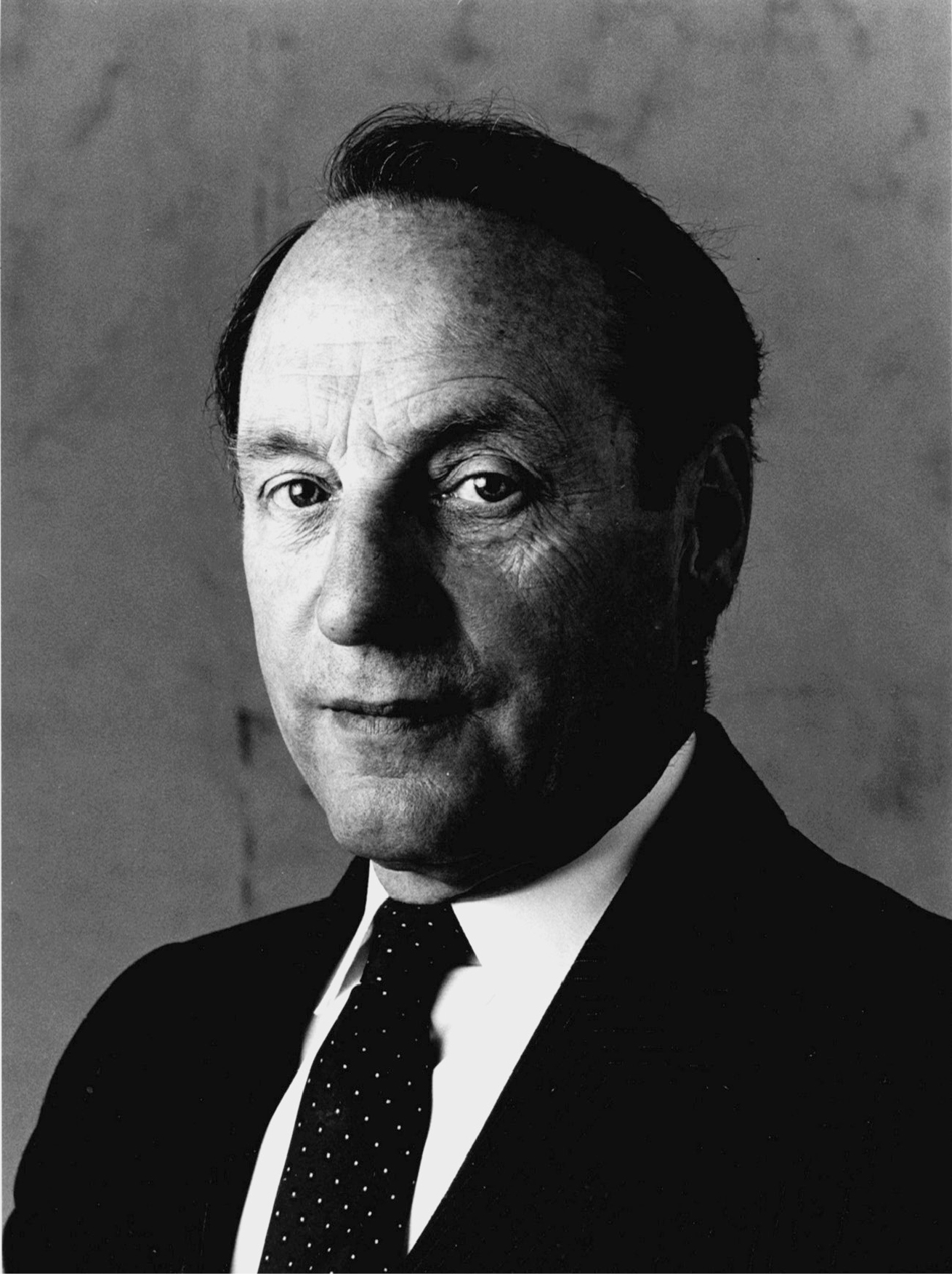

Noel Gilroy Annan, Baron Annan

by Walter Bird, bromide print, 21 June 1965

Reproduced by permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London

by Bernard Lee (“Bern”) Schwartz, dye transfer print, 6 July 1977

Reproduced by permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London

by John Gay, vintage bromide print, 1949

Reproduced by permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London

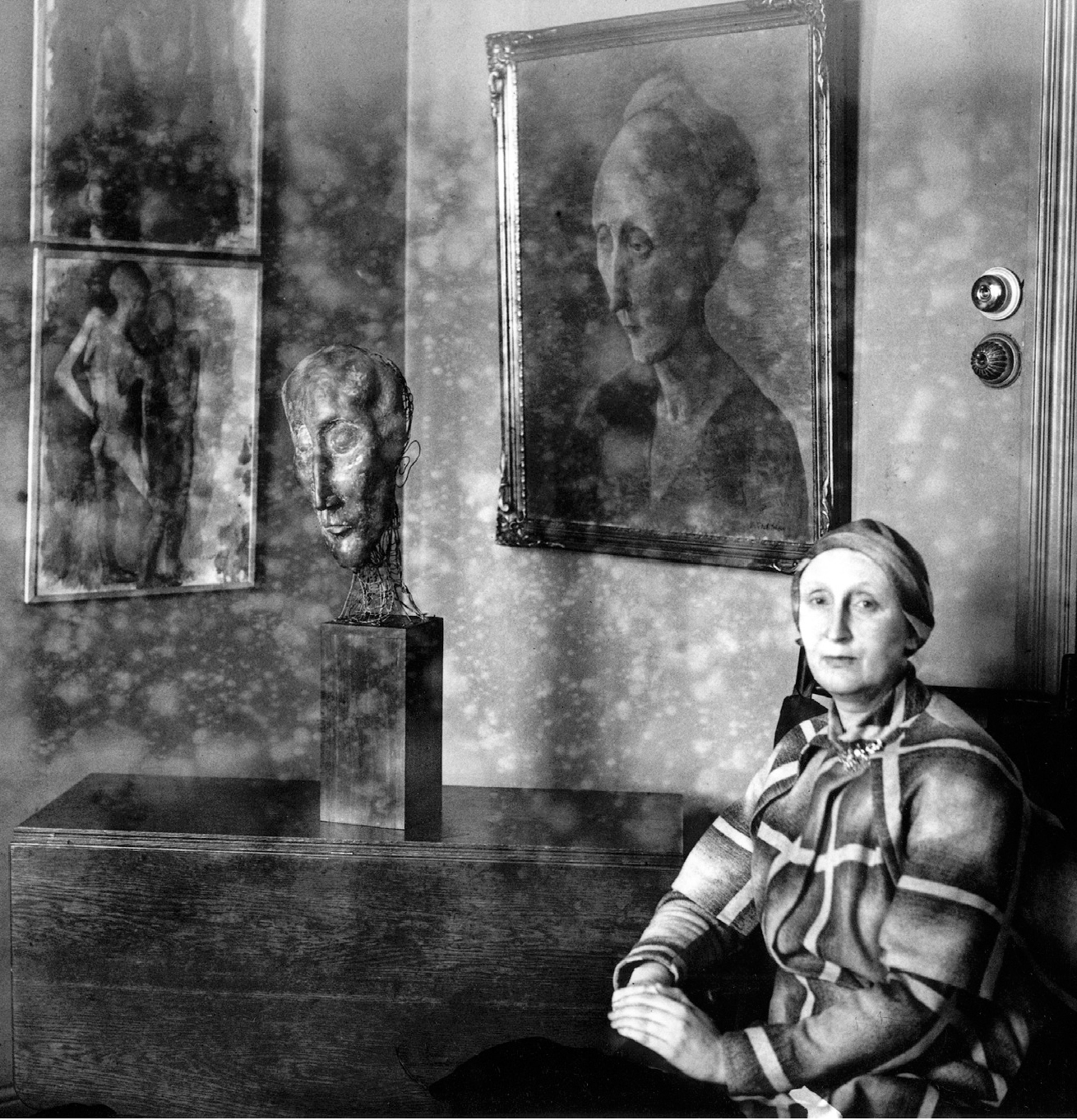

Sir Maurice Bowra; Virginia Woolf

by Lady Ottoline Morrell, vintage snapshot print, June 1926

Reproduced by permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London

by Howard Coster, half-plate film negative, 1937

Reproduced by permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London

by Walter Bird, bromide print, 6 February 1963

Reproduced by permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London ← xi | xii →

by Godfrey Argent, bromide print, 19 June 1968

Reproduced by permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London

Harold Macmillan, 1st Earl of Stockton; Lady Dorothy Evelyn Macmillan (née Cavendish)

by unknown photographer, bromide print, December 1959

Reproduced by permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London

Cyril John Radcliffe, 1st Viscount Radcliffe

by Elliot & Fry, quarter-plate glass negative, 3 October 1961

Reproduced by permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London

by Lady Ottoline Morrell, vintage snapshot print, June 1926

Reproduced by permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London

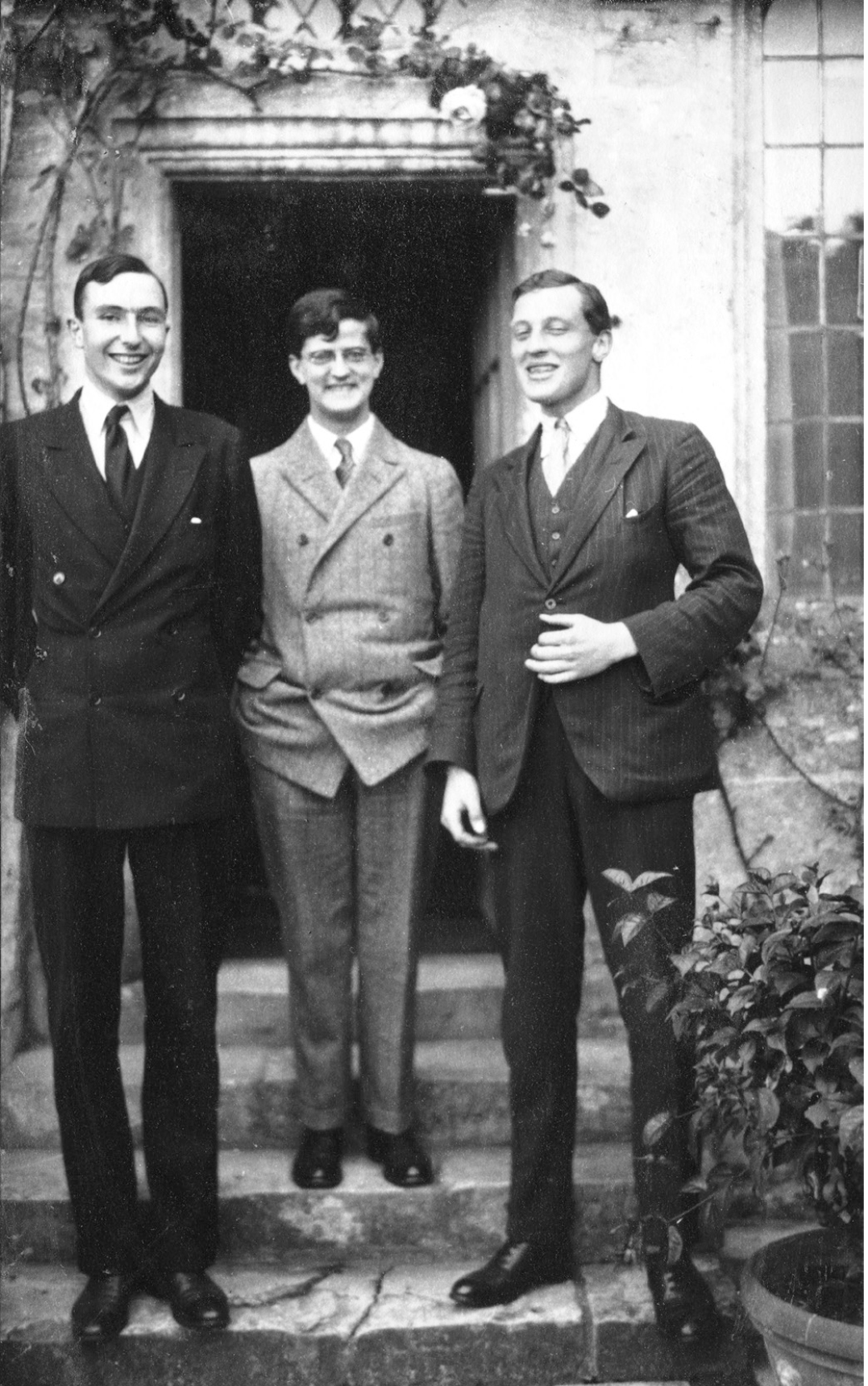

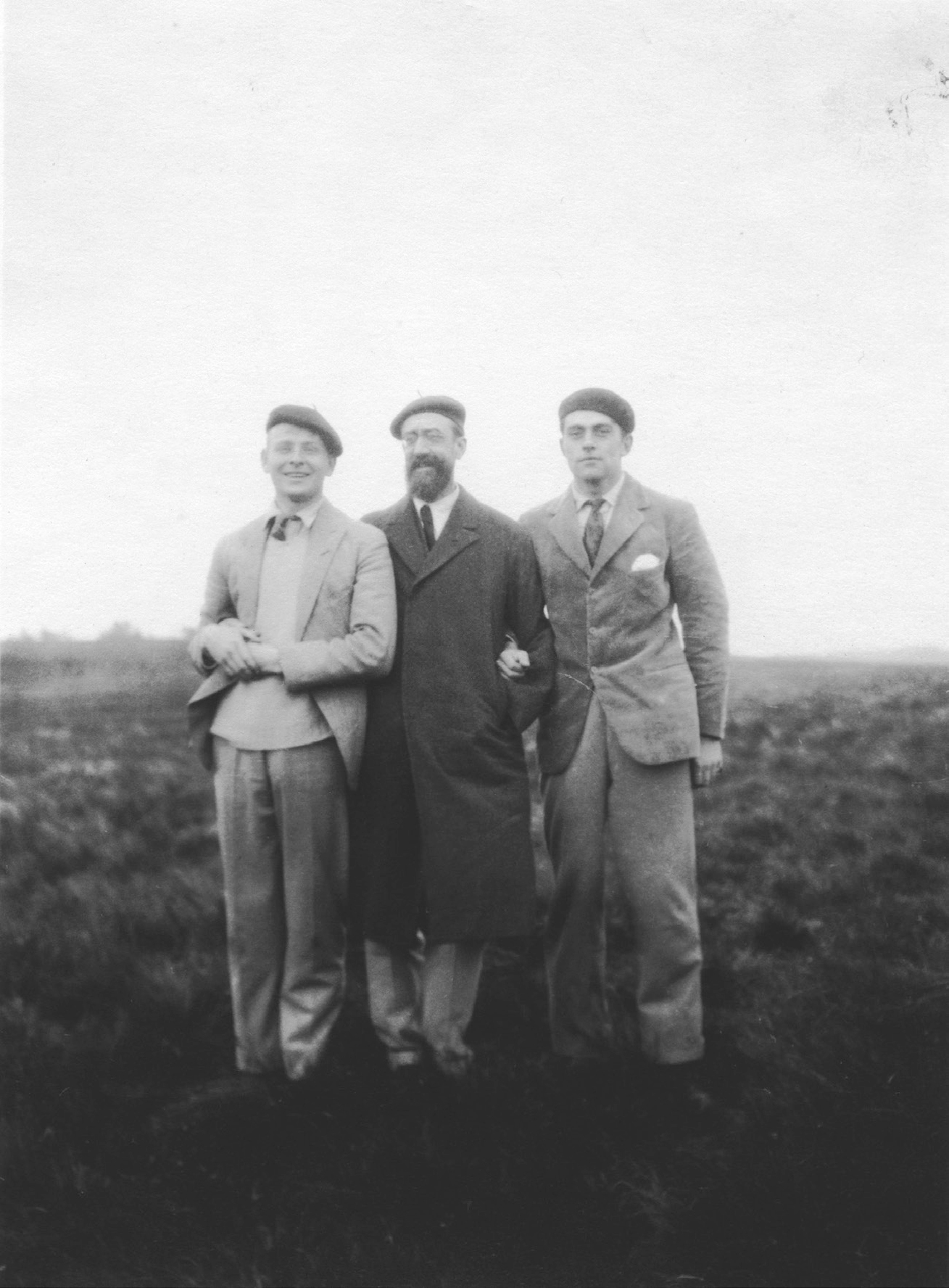

Wogan Phillips, 2nd Baron Milford; Lytton Strachey; Dadie Rylands

by unknown photographer, bromide snapshot print, 1926

Reproduced by permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London

by Fox Photos Ltd, modern bromide print, 1931

Reproduced by permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London ← xii | xiii →

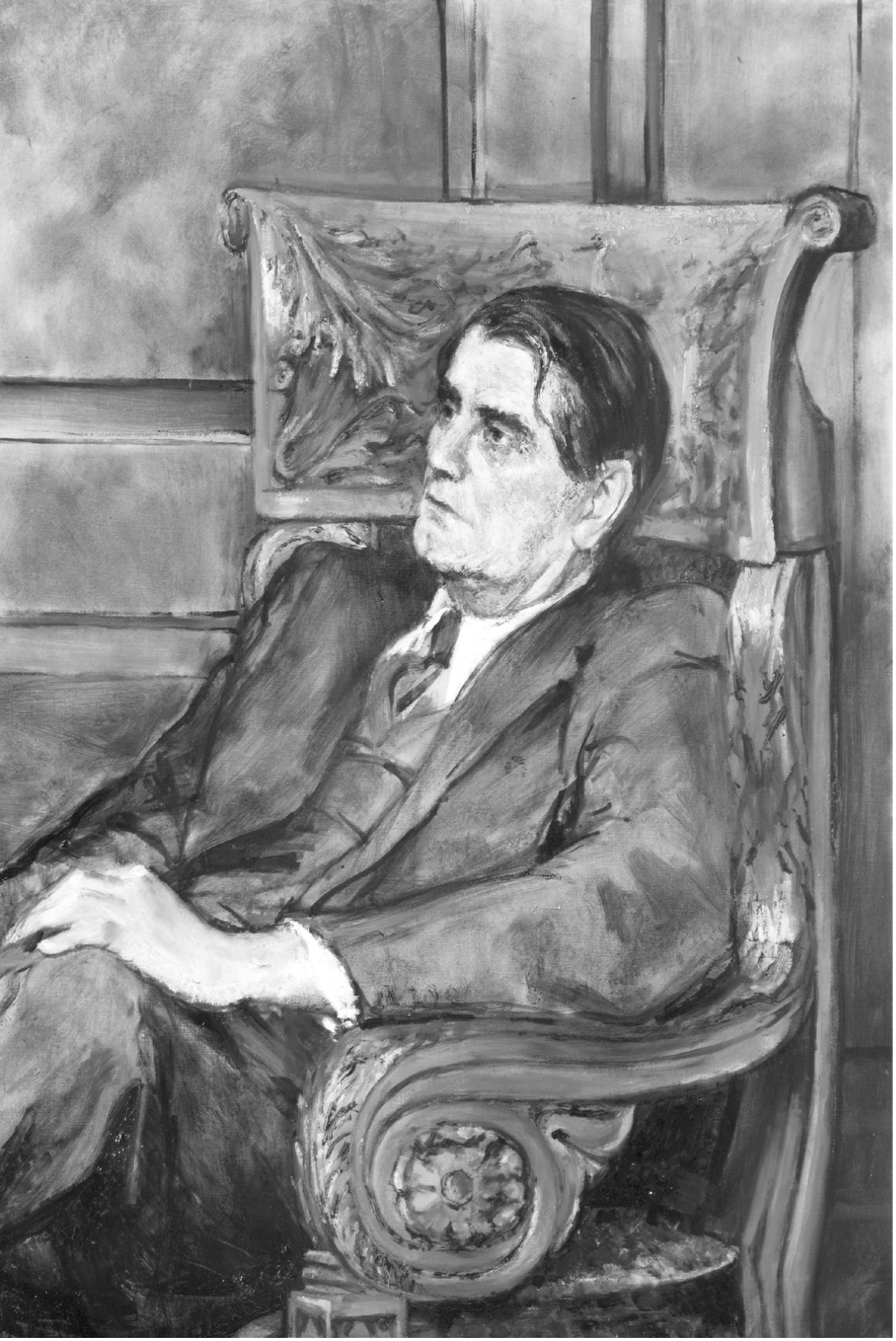

Hugh Redwald Trevor-Roper, Baron Dacre of Glanton

by Godfrey Argent, bromide print, 6 August 1969

Reproduced by permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London

by unknown photographer

Reproduced by permission of the Warden and Fellows of All Souls College, Oxford

portrait by Derek Hill

Reproduced by permission of the Trustees of the Derek Hill Foundation and the Warden and Fellows of All Souls College, Oxford

Richard Orme Wilberforce, Baron Wilberforce

by Elliot & Fry, quarter-plate glass, 1961

Reproduced by permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London

by Dr Martin West O. M.

Reproduced by permission of Dr Stephanie West and the Warden and Fellows of All Souls College, Oxford

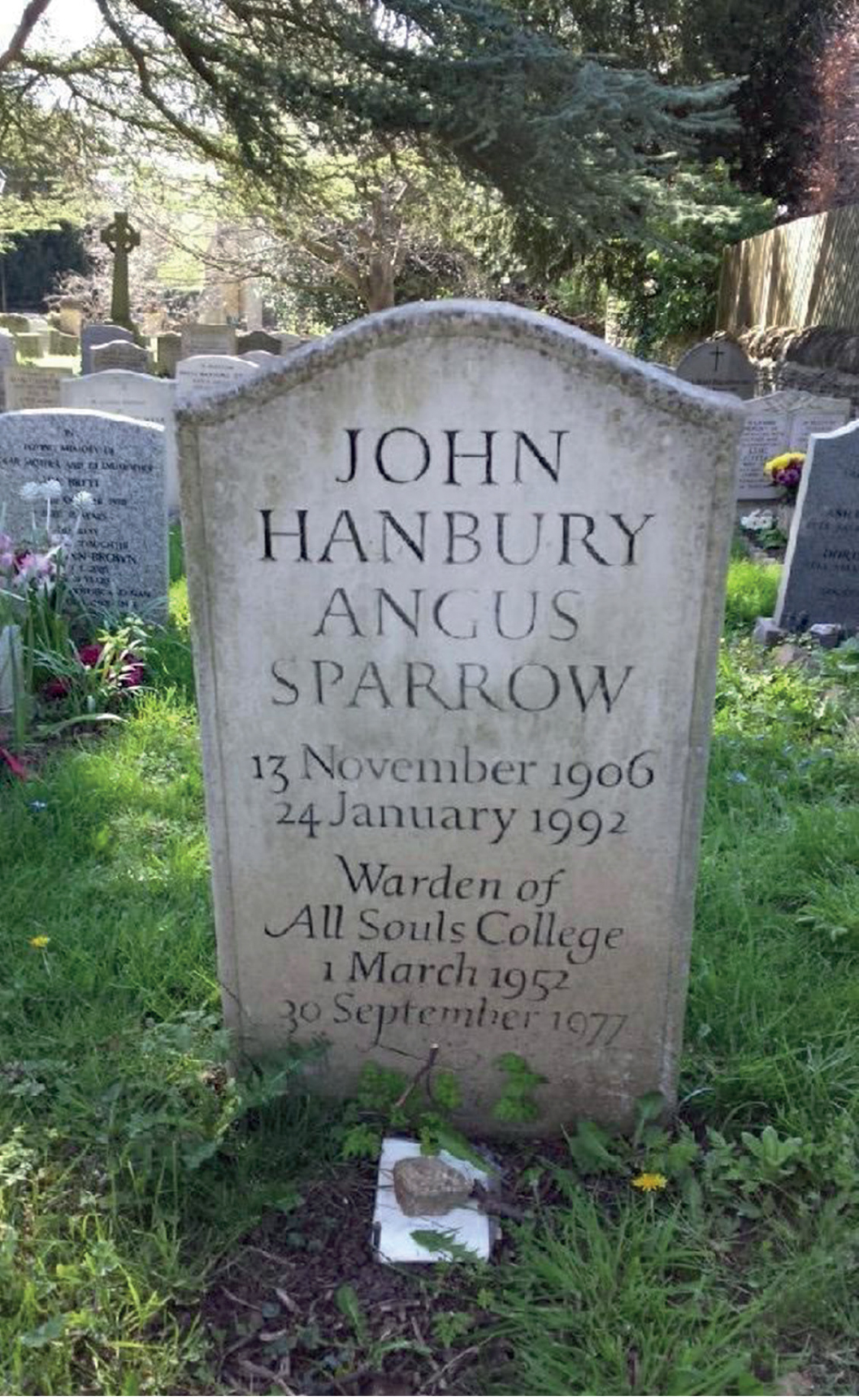

John Sparrow’s Gravestone, Iffley, Saint Mary’s churchyard

Photographer: jongee 175

Transcriber: Rob Dickens

Courtesy of Billion Graves

<http://www.billiongraves.com> ← xiii | xiv →

Noel Gilroy Annan, Baron Annan

by Walter Bird, bromide print, 21 June 1965

Reproduced by permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London

by Bernard Lee (“Bern”) Schwartz, dye transfer print, 6 July 1977

Reproduced by permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London

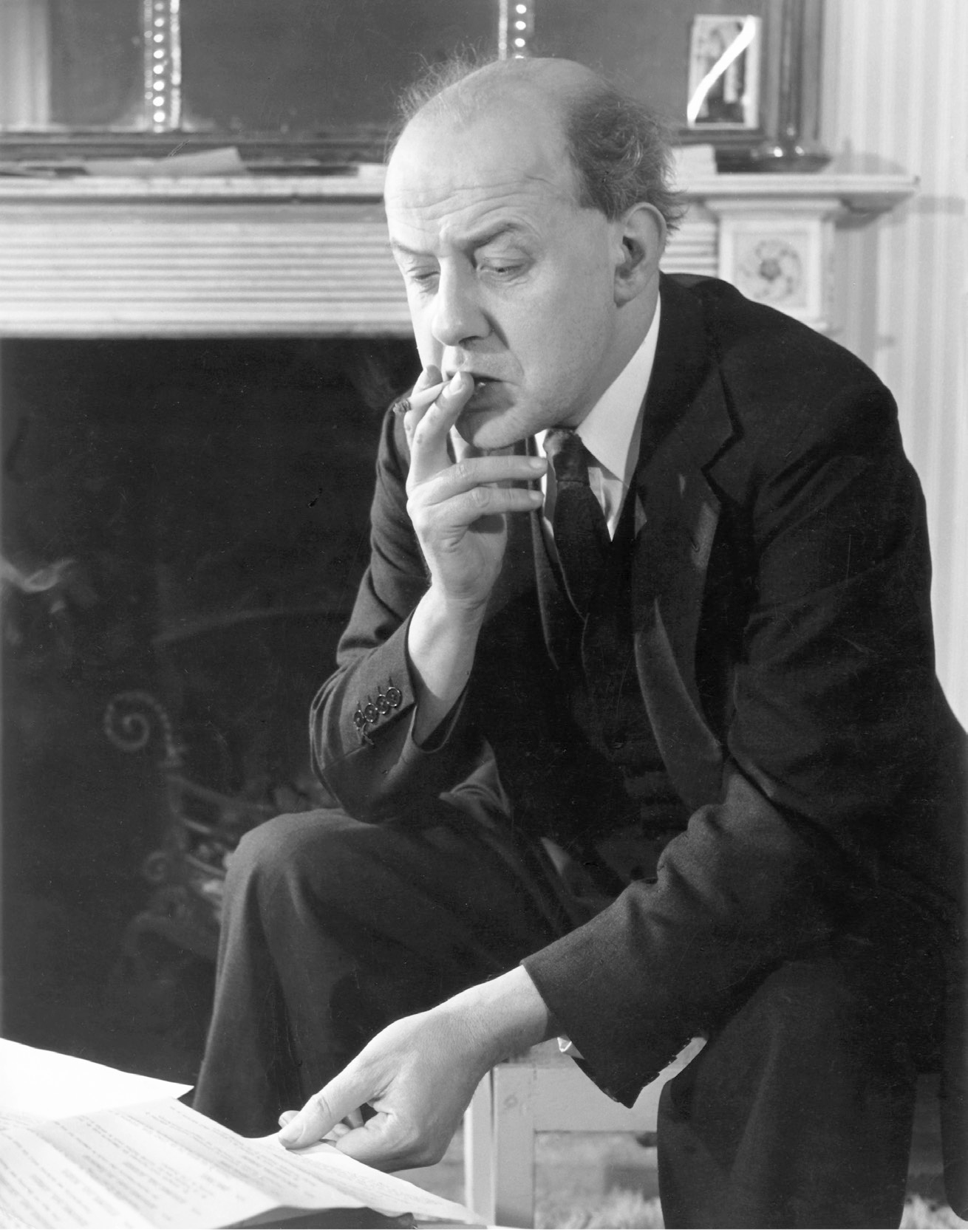

by John Gay, vintage bromide print, 1949

Reproduced by permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London

Sir Maurice Bowra; Virginia Woolf

by Lady Ottoline Morrell, vintage snapshot print, June 1926

Reproduced by permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London

by Howard Coster, half-plate film negative, 1937

Reproduced by permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London

by Walter Bird, bromide print, 6 February 1963

Reproduced by permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London

by Godfrey Argent, bromide print, 19 June 1968

Reproduced by permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London

Harold Macmillan, 1st Earl of Stockton; Lady Dorothy Evelyn Macmillan (née Cavendish)

by unknown photographer, bromide print, December 1959

Reproduced by permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London

Cyril John Radcliffe, 1st Viscount Radcliffe

by Elliot & Fry, quarter-plate glass negative, 3 October 1961

Reproduced by permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London

by Lady Ottoline Morrell, vintage snapshot print, June 1926

Reproduced by permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London

Wogan Phillips, 2nd Baron Milford; Lytton Strachey; Dadie Rylands

by unknown photographer, bromide snapshot print, 1926

Reproduced by permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London

by Fox Photos Ltd, modern bromide print, 1931

Reproduced by permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London

Hugh Redwald Trevor-Roper, Baron Dacre of Glanton

by Godfrey Argent, bromide print, 6 August 1969

Reproduced by permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London

by unknown photographer

Reproduced by permission of the Warden and Fellows of All Souls College, Oxford

portrait by Derek Hill

Reproduced by permission of the Trustees of the Derek Hill Foundation and the Warden and Fellows of All Souls College, Oxford

Richard Orme Wilberforce, Baron Wilberforce

by Elliot & Fry, quarter-plate glass, 1961

Reproduced by permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London

by Dr Martin West O. M.

Reproduced by permission of Dr Stephanie West and the Warden and Fellows of All Souls College, Oxford

John Sparrow’s Gravestone, Iffley, Saint Mary’s churchyard

Photographer: jongee 175

Transcriber: Rob Dickens

Courtesy of Billion Graves

John Sparrow was “keen to be remembered in a biography” – or so he told his closest friend, John Lowe, asking him to write it. Lowe and Sparrow had got to know each other in 1951, and they remained in close contact. From 1980 onwards Lowe visited Sparrow quite regularly, and he began collecting source material, which, after 1988, Sparrow put at his disposal at Beechwood House, the place where he lived after his retirement from the Wardenship of All Souls College, Oxford. While Lowe was reading the sources Sparrow would interfere from time to time, asking his biographer how he was “getting on with it”. From 1988 until Sparrow’s death in 1992 Lowe spent several weeks a year at Beechwood House working on the biography. Six years later his book was published.1

Lowe’s biography was exceptionally well received by the critics. Philip Ziegler wrote that it was “a telling portrait” – “well-written, thoughtful, understanding and above all fair”. Anthony Smith observed that the book gave an “affectionate portrait of a man divided between the calls of scholarship, literature and the legal profession, but who succumbed to the dutiful temptation of a wardenship of his college”. Hugh Trevor-Roper thought it was “a friendly but honest biography”, and Richard Davenport-Hines wrote that “John Lowe’s shrewd, affectionate, old-fashioned biography tenderly evokes and perfectly befits its subject.” All in all, Lowe had done a very good job. And yet Lowe’s estimation of Sparrow’s character was not complimentary. He regarded Sparrow as deeply selfish, not always loyal to his close friends, a “vain man, with a theatrical streak”, evasive and contradictory in his correspondence.

Some of Sparrow’s closest friends registered different views on how they saw Sparrow. Noel Annan remarked that Sparrow had “a genius for ← xv | xvi → friendship”. Not only was Sparrow “a charmer, he was a fascinator”,2 a romantic who “cared very much for people”.3

Sparrow’s colleague at All Souls, Robin Briggs, now Emeritus Fellow, wrote an excellent essay in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, not sparing him some critical strictures. “The formal outlines of Sparrow’s life and writings,” wrote Briggs, “and even those writings themselves, give a very inadequate impression of a most remarkable man. He was essentially a bundle of contradictions: a passionate and independent person who outwardly took a highly conventional position, a scholar and college head who had little sympathy for most academics, a lover of literature and the arts with a curiously narrow range of taste, a master of English prose who wrote no major book, and a believer in high moral standards who occasionally behaved very badly.”4 This criticism sounds accurate, and should not raise resentment.

Another of Sparrow’s friends, Isaiah Berlin, acquaints us with the particular nature of Sparrow’s character. In his view:5

John’s interests in order of priority could be described as follows:

- Himself.

- Sex.

- At a great remove from these, old books.

- English literature in the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries.

- The classics, the visual arts, friendships with colleagues and school friends etc., and the edges of political life. ← xvi | xvii →

The College, Berlin maintained, came “low in the list”, even though “he felt it to be his home for all those years”. Sparrow was, Berlin judged, “the best company in the world, so far as I am concerned. His wit, his irony, his charm, his sheer intelligence, indeed his brilliance, and his total lack of fear, moral and physical, and his independence, were unique in my experience. I have known him, I suppose, since 1931 and he did not change very much during my lifetime.”6 “There were certain qualities which […] were unusual”, but he “totally lacked public spirit” and it was this “that prevented his being given an honour by the state”. Berlin continues:

In College, to which he was in a sense devoted, his principal achievement was blocking – with the greatest ingenuity, style, and brilliance – the slightest change in its arrangements. He did not always succeed, of course, but his efforts in that direction were wonderful to behold. […]7 I cannot deny that I watched his manoeuvres to outwit and stymie his colleagues with the most fascinated, if somewhat disapproving, admiration. His virtuosity in that respect was, in my experience, unparalleled. He saw it as saving the College. Few of his colleagues saw it in that light.8

Berlin himself would have been less inclined to write Sparrow’s biography. It was, Berlin wrote to Lowe, a “very difficult task to write the real life of our friend. There is nothing I wouldn’t do to avoid having to do this myself.”9 Nevertheless Lowe undertook the task. His work is not a panegyric. He displayed Sparrow’s true character; related his faults and values. The biography is both instructive and entertaining. And yet there is something lacking. Lowe did not make complete use of the material accessible to him. We have attempted to fill this gap in the present volume.

I sent a synopsis of my work to several distinguished historians, specialists in modern British history, for them to comment on it. The response was diverse. One or two were not convinced that John Sparrow deserved ← xvii | xviii → a whole volume, or that we needed another biography of him, because: he was a nonentity outside Oxford; he was not a normal Warden or a normal scholar (he was “lazy, procrastinating, timid in both functions”); he published little, and his publications were narrow; whatever “his many attainments, and the intrinsic interest of his character”, Sparrow “is too much a man of his own times to be of very great interest to our own.”

And yet I was encouraged to attempt to fill the gap that is apparent in Lowe’s biography. The present work is not entirely a revisionist portrait of Sparrow. It should be seen as a complementary volume to Lowe’s. Mine is perhaps a more admiring portrait.

Lowe produces abundant correspondence between Sparrow and his mother, but does not mention one particular aspect of their relationship. Margaret was an instructing mother to Sparrow. She herself wrote some interesting essays and even a short one-act play. She wrote on the character of Victorian society, especially the lot of women, and on the values of a decent man. All this, we believe, greatly influenced Sparrow’s interest in literature and his later views on social behaviour and moral values. We have therefore included in our book some of Margaret’s writings, which have previously been unpublished.

Further knowledge of a man’s character may be gained by his correspondence with friends. Lowe published some of it, but not the most relevant. Sparrow’s correspondence was voluminous, but we have furnished the reader with samples of his correspondence with those with whom he was on intimate terms – Noel Annan, John Betjeman, Isaiah Berlin, Maurice Bowra, Kenneth Clark, Roy Harrod, Philip Larkin, Harold Macmillan, George Rylands, Edith Sitwell and Hugh Trevor-Roper.10 These illustrate the quickness of his feelings, his hospitality, his virtues. There are many significant events in Sparrow’s life to which Lowe has barely referred. We have tried to make up for this deficiency and to describe them fully. Our book includes: prep school reports; a full record of Sparrow’s time at Winchester College with complete school and headmaster’s reports and details of the passion for debating and poetry he showed there; an analysis of his Half-lines and ← xviii | xix → Repetitions in Virgil (1931) and his Sense and Poetry (1934); the War Office reports on the morale of the army at home (1942), in Italy, the Middle East (1944), and in India and South-East Asia (1945); the Visiting Fellowship Scheme at All Souls College; Sparrow’s controversies; Sparrow’s favourite Japanese pupil; Sparrow’s stance towards the Oxford student revolt in 1968; his delight in writing letters; his failure to be elected Professor of Poetry at Oxford; his BBC broadcasts; and finally his orations on funeral occasions. None of this information has been published before, and it will contribute to our reaching a just estimate of Sparrow’s life.

Isaiah Berlin suggests that Sparrow’s public life was “of little outstanding interest”: he was basically an academic figure. Nor should “his private life” offer “terrible obstacles” [Berlin] to the biographer. True, Sparrow was not a great poet, nor the great critic of his generation, but the very few essays he wrote have established him as a versatile author. And his private life should be seen as it really was: it had very little effect on his professional or academic activities. If he did not entirely distinguish himself in academic life as people had expected of him, it was not because he was deficient in talent; it was because he preferred social and administrative engagement to the sanctity of scholarship. It has been suggested that Sparrow’s life was not entirely perfect, but whose is?

On what, then, should Sparrow’s fame chiefly rest? First, his life should be of interest in its own right. Secondly, his activities throw light on the eccentricities of All Souls College. Although Sparrow firmly regarded the latter as relics of empty pride and self-deception, he partly preserved them. But he proceeded from the very beginning to be a normal Warden and carry on as a normal scholar. He quite explicitly set himself a plan of getting things back to normality. For centuries All Souls College had pretended to customs and concessions above those of mere mortals. He released the College from a centuries-old adherence to its own eccentricities. With the death of Sparrow, the myth of the “immortality” of All Souls College and of its Fellows vanished. All Souls still claims to have certain peculiarities. This oddity is perhaps no more spectacular than peculiar antiquarian tastes prevalent in other colleges. One of my critics suggests that this seems a “bizarre claim”: the College, he believes, “is unique in not admitting either undergraduates or postgraduates – which makes it literally abnormal!” ← xix | xx → The College “is also unique in retaining a competitive entrance examination. Both of these things give it a very singular identity and it struggles to shake off a reputation for being a graveyard for young scholars.” Another distinguished scholar who was a Visiting Fellow at All Souls admits that the College “is exceptional in its attainments, atmosphere and privileges” and that he has “never known anywhere in the world where less time is wasted, where intelligence is more focused or which is altogether of the utmost respect.” One must, however, acknowledge, that once a fellow is elected to All Souls there occurs some mental transformation. It may not reflect some shadow of eccentricity, but perhaps an element of obscure snobbishness.

John Sparrow never liked what was “common” and “ordinary”. He always aspired to be different. That is why the subtitle given to this book, “I loathe all common things”, appeared suitable. This is the motto Sparrow gave to the poem he submitted at Winchester College for the King’s Gold Medal for English Verse. He borrowed it from a line of the Ancient Greek poet Callimachus. The motto somehow epitomises Sparrow’s whole life.

It has been my purpose to acquaint the reader with Sparrow’s achievements and promise, as well as his faults and follies. The reader should see him as he really was. His own letters and his words on the air will best illustrate his peculiarities, and thus show up his character. There is no resort to subjective assessment or speculation.

| Jowett Walk Buildings Trinity Term 2016 Oxford | Peter Raina |

1 John Lowe, The Warden: A Portrait of John Sparrow (London: HarperCollins Publishers, 1998). The paperback edition from which we quote in our present study appeared in 1999.

2 Noel Annan, “The Don as Dilettante – John Sparrow”, in Noel Annan, The Dons. Mentors, Eccentrics and Geniuses (London: HarperCollins Publishers, 2000), p. 193.

3 Ibid., p. 195.

4 Robin Briggs, “John Hanbury Angus Sparrow, 1906–1992”, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, edited by H. C. G. Mathew and Brain Harrison (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), Volume 51, p. 755.

5 Isaiah Berlin to John Lowe, in a private letter dated 27 February 1989. Bodleian Weston Library, Oxford. MS Berlin 224, fols 25, 30–7, 123–4. See also Isaiah Berlin, Affirming: Letters 1975–1997, edited by Henry Hardy and Mark Pottle with the assistance of Nicolas Hall (London: Chatto & Windus, 2015), pp. 358–9.

6 Ibid.

7 Ellipses in squared brackets indicate omissions.

8 Isaiah Berlin to John Lowe, in a private letter dated 27 February 1989. Bodleian Weston Library, Oxford. MS Berlin 224, fols 25, 30–7, 123–4. See also Isaiah Berlin, Affirming: Letters 1975–1997. op. cit., pp. 358–9.

9 Ibid.

10 For biographical and further details see under the section: “Keep Your Friendships …”, later in this volume.

This volume is almost entirely based on the unpublished Sparrow Papers deposited in the Codrington Library, All Souls College, Oxford. The Warden and the Fellows of All Souls College, who are literary executors of these Papers kindly agreed to grant, first, access, and then permission to quote them in print. The author most gratefully acknowledges this help. The work in these Papers was at the beginning facilitated by the then Librarian in Charge and Archivist, Dr Norma Aubertin-Potter. After her retirement, the Librarian in Charge and Conservator, Miss Gaye Morgan, MA took over and she has been uncommonly helpful. There are hardly words to thank her for her generosity, profundity and dedication. All along, she has patiently and efficiently answered the author’s enquiries and met his needs. I am greatly indebted to her. This indebtedness has to be extended to the Librarian, Professor Colin Burrow.

The author owes deep gratitude to the following copyright holders for giving permission to print these persons’ respective unpublished letters to John Sparrow.

- The Earl of Stockton: Harold Macmillan’s letters.

- Paul Betjeman: John Betjeman’s letters.

- Emma Craigie: William Rees-Mogg’s letters.

- Henry Mark Harrod and Tanya Harrod: Roy Harrod’s letters.

- “Unpublished writings of G. H. W. Rylands, copyright the Provost and Scholars of King’s College Cambridge 2017”: Dadie Rylands’ letters.

- BBC Written Archives Centre, Caversham, Reading: John Sparrow’s broadcasts.

- Bodleian Weston Library, Oxford: MS Berlin; MS Macmillan.

- Juliet Annan and “Letters to John Sparrow” from Letters to John Sparrow by Noel Annan. Previously unpublished. Copyright © Noel Annan. Reproduced by permission of the author c/o Rogers, Coleridge & White Ltd, 20 Powis Mews, London W11 1JN. ← xxi | xxii →

- The Warden and Fellows of Wadham College, Oxford: MS Bowra.

- The Society of Authors as the Literary Representative of the Estate of Philip Larkin: letters from Philip Larkin to John Sparrow; also letter from Virginia Woolf to John Sparrow.

- Christ Church, Oxford: the Dacre Papers.

- The Archives and Records of HRH The Prince of Wales.

- Extracts from Unpublished letters by Edith Sitwell to John Sparrow reprinted by permission of Peters Fraser & Dunlop (<http://www.Petersfraserdunlop.com>) on behalf of the Estate of Edith Sitwell.

- The British Library, London; the Roy Harrod papers.

- The Tate Library & Archives, London; the Kenneth Clark papers.

- Harry Ransom Centre, The University of Texas at Austin; the Edith Sitwell papers.

- The National Portrait Gallery, London.

- The Trustees of the Isaiah Berlin Literary Trust: permission to use extracts from letters from Isaiah Berlin to John Sparrow.

While every effort has been made to trace copyright holders, if any have been inadvertently overlooked, the author will be happy to acknowledge them in future editions.

The author further feels obliged to record his gratitude to people, who have in one way or another been very helpful:

Miss Jasmin Allousch

Miss Juliet Annan

Mr Jon Ashby, Copy-editor

Miss Sarah Baxter, Contracts Advisor & Literary Estates, The Society of Authors, London

Dr Sarah Beaver, Bursar, All Souls College, Oxford

Mr Matthew Chipping, BBC Written Archives Centre

Miss Emma Clarke

Miss Emma Craigie

Miss Judith Curthoys, Archivist, Christ Church, Oxford ← xxii | xxiii →

Dr Richard Davenport-Hines, sometime Visiting Fellow, All Souls College, Oxford

Mr Cliff Davies, former Archivist, Wadham College, Oxford

Miss Alice Emmott

Miss Suzanne Foster, Archivist, Winchester College, Winchester

Mr Ben Goodwin

Mr Jeffrey Hackney, Archivist, Wadham College, Oxford

Dr Henry Hardy, Honorary Fellow, Wolfson College, Oxford

Mrs Isabel D. Holowaty, Bodleian History Librarian, Oxford

Mr Michael Hughes, Bodleian Weston Library, Oxford

Dr Edward Hussey, Emeritus Fellow, All Souls College, Oxford

Mr Jeff Johnson, Archives Manager to HRH The Prince of Wales

Professor Christopher Kelly, President, Corpus Christi College, Cambridge

Mr Tim Kirtley, College Librarian, Wadham College, Oxford

Dr Patricia McGuire, Archivist, King’s College, Cambridge

Mrs Lucy Melville, Publisher

Mrs Keeley Mortimer

Mr Nicholas Owen of Rogers, Coleridge and White Ltd, London

Dr Mark Pottle, Fellow, Wolfson College, Oxford

Miss Sharon Rubin, Permissions Manager, Peters Fraser & Dunlop, London

Dr Graham Speake

Dr David Sutton, Watch, Reading University Library, Reading

Dr Simon Skinner, Balliol College, Oxford

Miss Jennifer Thorp, Archivist, New College, Oxford

Mrs Emma Tristram

Sir Michael Wheeler-Booth

Prof Blair Worden, Executor of the Dacre (Hugh Trevor-Roper) literary estate ← xxiii | xxiv →

Details

- Pages

- XXIV, 826

- Publication Year

- 2017

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781787075061

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781787075078

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781787075085

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781787075092

- DOI

- 10.3726/b11079

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2018 (February)

- Keywords

- John Sparrow All Souls College, Oxford Bloomsbury Set

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, New York, Wien, 2017. XXIV, 826 pp., 2 coloured ill., 16 b/w ill.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG