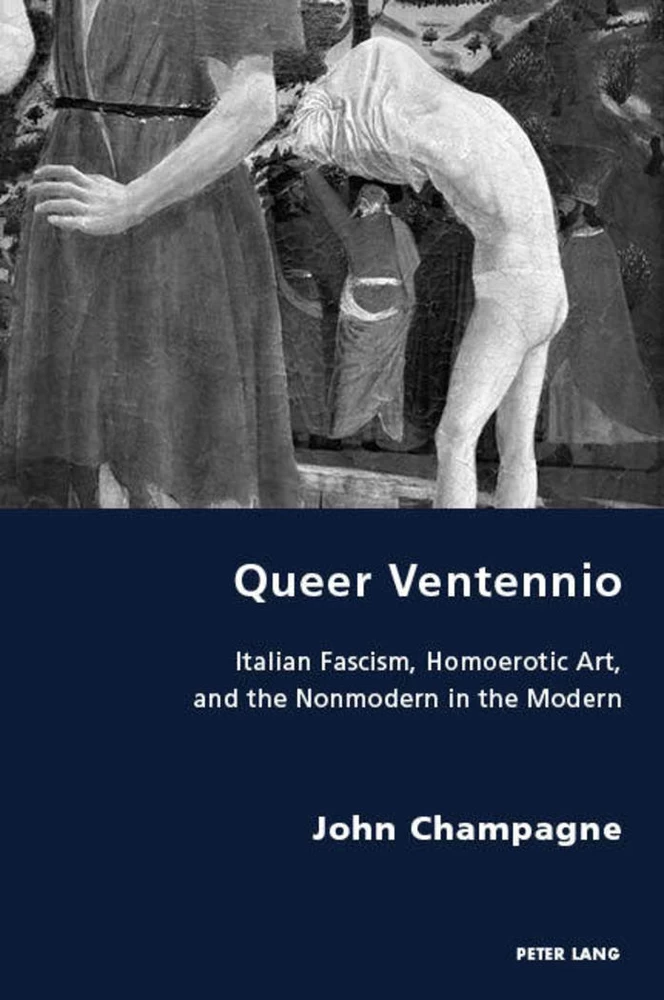

Queer Ventennio

Italian Fascism, Homoerotic Art, and the Nonmodern in the Modern

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Queer Ventennio

- Chapter 1: Queer Unhistoricism

- Chapter 2: Giovanni Comisso

- Chapter 3: Filippo de Pisis

- Chapter 4: Corrado Cagli

- “Quasi una conclusione”: On Saba’s Ernesto

- Bibliography

- Index

- Series index

Queer Ventennio

Italian Fascism, Homoerotic Art,

and the Nonmodern in the Modern

PETER LANG

Oxford • Bern • Berlin • Bruxelles • New York • Wien

Bibliographic information published by Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek

Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data is available on the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress.

Cover image: Photo by Sailko https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/User:Sailko. Creative Commons 3.0.

Cover design by Peter Lang Ltd.

ISSN 1662-9108

ISBN 978-1-78997-224-5 (print) • ISBN 978-1-78997-225-2 (ePDF)

ISBN 978-1-78997-226-9 (ePub) • ISBN 978-1-78997-227-6 (mobi)

© Peter Lang AG 2019

Published by Peter Lang Ltd, International Academic Publishers,

52 St Giles, Oxford, OX1 3LU, United Kingdom

oxford@peterlang.com, www.peterlang.com

John Champagne has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as Author of this Work.

All rights reserved.

All parts of this publication are protected by copyright.

Any utilisation outside the strict limits of the copyright law, without the permission of the publisher, is forbidden and liable to prosecution.

This applies in particular to reproductions, translations, microfilming, and storage and processing in electronic retrieval systems.

This publication has been peer reviewed.

Currently working at the intersection of queer theory, Italian Studies, and art, music, and literary criticism, John Champagne is Professor of English and Program Chair of Global Languages and Cultures at Penn State Erie, the Behrend College. He is the author of two novels, The Blue Lady‘s Hands (Lyle Stuart, 1988) and When the Parrot Boy Sings (Meadowlands, 1990), and three previous scholarly monographs, The Ethics of Marginality (University of Minnesota Press, 1995), Aesthetic Modernism and Masculinity in Fascist Italy (Routledge, 2013), and Italian Masculinity as Queer Melodrama, Caravaggio, Puccini, and Contemporary Cinema (Palgrave, 2015). His articles on such varied topics as post-colonial feminist literature, Italian Jewish Memorial sites, and gay porn have appeared in such journals as College English, Modern Italy, and Cinema Journal. Champagne received a Fulbright grant to teach at the University of La Manouba in Tunis, Tunisia, and was the 2018–2019 Penn State Laureate. He and his husband Richard Krone divide their time between Perugia, Italy, and Erie, Pennsylvania.

About the book

Given fascist proscriptions against homosexuality, a surprising number of artists under Mussolini’s regime were queer. Exploring the contribution of Italy to our understanding of both the history of homosexuality and European modernism, this ground-breaking study analyses three queer modernists – writer Giovanni Comisso, painter and writer Filippo de Pisis, and painter Corrado Cagli. None self-identified as fascists; none, however, were consistent critics of the regime. All understood their own sexuality via the idea of the primitive – a discourse fascism also employed in its efforts to secure consent for the dictatorship. What happens when we return to these men and their work minus the assumption that our most urgent task is identifying their fascist tendencies or political quietism? Variously infantilized, pathologized, marginalized, and stigmatized, treated as both cause and effect of fascism, queer ventennio artists are an easy target, not brave or selfless or savvy enough to see their common struggle with fascism’s other victims. Revisiting their works and lives with an eye toward neither rehabilitation nor condemnation allows us to ponder more carefully the relationship between art and politics, how homophobia has structured art criticism, the need to further bring queer perspectives to Italian cultural analysis, and how such men disrupt our sense of modern homo/heterosexual definition.

This eBook can be cited

This edition of the eBook can be cited. To enable this we have marked the start and end of a page. In cases where a word straddles a page break, the marker is placed inside the word at exactly the same position as in the physical book. This means that occasionally a word might be bifurcated by this marker.

Contents

Index←v | vi→ ←vi | vii→

Figure 1: Carlo Levi, Self-portrait, c. 1930–2. © 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome

Figure 2: Filippo de Pisis, Youth Playing the Flute, 1945. © 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome

Figure 3: Portrait of Giovanni Comisso in Paris, 1927. Courtesy Fondo Giovanni Comisso

Figure 4: De Pisis in his Paris studio, 1932. Courtesy Associazione per Filippo de Pisis, Milano

Figure 5: Filippo de Pisis, Reclining Nude from Behind, 1930. © 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome

Figure 6: Filippo de Pisis, Nude on Tiger Skin (Robert), 1931. © 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome

Figure 7: Filippo de Pisis, Reclining Nude Leaning on his Elbows, 1940. © 2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome

Figure 8: Corrado Cagli – Camp Callan – California, 1942. Courtesy Archivio Corrado Cagli←vii | viii→

Figure 9: Corrado Cagli, March on Rome, 1929–30, (reverse side view), private collection, Umbertide. Courtesy Archivio Corrado Cagli

Figure 10: Corrado Cagli, The Shoveler, 1929–30, private collection, Umbertide. Courtesy Archivio Corrado Cagli

Figure 11: Corrado Cagli, The Battle for Grain, 1930, private collection, Umbertide. Courtesy Archivio Corrado Cagli

Figure 12: Corrado Cagli, The Battle for Grain, 1930, private collection, Umbertide. Courtesy Archivio Corrado Cagli

Figure 13: Alberto Ziveri, Birilli Players, 1934. Courtesy collezione Giuseppe Iannaccone

Figure 14: Corrado Cagli, Saint Thomas, 1936–7, collezione GAM, Torino. Courtesy Archivio Corrado Cagli

Figure 15: Corrado Cagli, The Neophytes, 1934, private collection, Rome. Courtesy Archivio Corrado Cagli←viii | ix→

This book could not have been written without the assistance of numerous colleagues and friends. At Penn State, Robert Caserio, David Christiansen, Sharon Dale, Dan Frankfurter, Ivor T. Knight, and Arpan Yagnik all contributed to its completion; Alexis Weber assisted in the preparation of the Bibliography. I owe a specific debt of gratitude to Amy Carney, Sara Luttfrig, and Janet Neigh for their extensive and thoughtful responses to early drafts, to Massimo Verzella for his patience in discussing certain Italian texts with me, to Eric Corty for nominating me as the Penn State 2018–19 laureate and providing me with the opportunity to share my work on Corrado Cagli at Penn State campuses across Pennsylvania, and to Matt Levy for his willingness to lend me his visual intelligence. Colleagues at other institutions, including Raffaella Cordisco, Maria Paola Corsentino, Keala Jewell, Benjamin A. Kahan, David Primo, Alessio Ponzio, Simona Storchi, and George Talbot, generously shared their expertise.

At Peter Lang, the series editors, Robert S. C. Gordon and Pierpaolo Antonello, were continual sources of encouragement. Two anonymous readers’ reports provided valuable advice for revision. Anthony Mason, Jonathan Smith, and Simon Phillimore shepherded the manuscript through the production process.

While the manuscript was already under consideration, I came across Raffaele Bedarida’s recent invaluable book on Cagli’s time in the US, and he graciously shared with me some of his insights.

Stephen Swanson offered detailed and invaluable commentary on how to trim an unwieldy manuscript. Annalisa Trapani rechecked my Italian translations.

Archivists and scholars at several Italian institutions generously assisted in providing permissions, images, and access to works, including Rischa Paterlini of the Collezione Giuseppe Iannaccone; Antonella Lavorgna of the Fondazione Carlo Levi; Dottoressa Anna Nicoletta Rigoni and the staff of the Museo Arte, Comune di Pordenone; Federica Sani of the Museo Filippo de Pisis; Maddalena Tibertelli de Pisis of the Associazione Filippo de Pisis; Giuseppe Briguglio and Alberto Mazzacchera of the Archivio Corrado Cagli;←ix | x→ Anna Maria Pianon of the Foto Archivio Storico di Trevignano; Alessandro Tonacci and Roberta Valbusa of the Archivio Fiumano, and the Reggiani family in Umbertide.

Massimo Monini, Jean-Christophe Clair, Lorenzo Fiorucci, Helena Palazzoli, Maurizio Pucci, and the whole staff of Rometti ceramics went well beyond giving generously of their knowledge of Cagli’s work, discussing the project with me, showing me around their wonderful factory, treating me to an Umbrian lunch, and arranging for me to visit the Casa Mavarelli-Reggiani.

A final thanks is due to my husband Richard Krone, whose technical support in preparing the manuscript, patience, and love continue to humble me some fifteen years after he first parked his bike on my front porch.←x | 1→

We inherit not “what really happened” to the dead but what lives on from that happening, what is conjured from it, how past generations and events occupy the force fields of the present, how they claim us, and how they haunt, plague, and inspirit our imaginations and visions for the future.

— Wendy O. Brown (2001: 150)

Details

- Pages

- X, 310

- Publication Year

- 2019

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781789972245

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781789972252

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781789972269

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781789972276

- DOI

- 10.3726/b15188

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2019 (November)

- Keywords

- Italian fascist art and literature Italian Modernist painting and literature Queer Italian Artists of the Fascist Years

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, New York, Wien, 2019. X, 310 pp., 15 fig. b/w

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG