Goethe and Anna Amalia: A Forbidden Love?

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

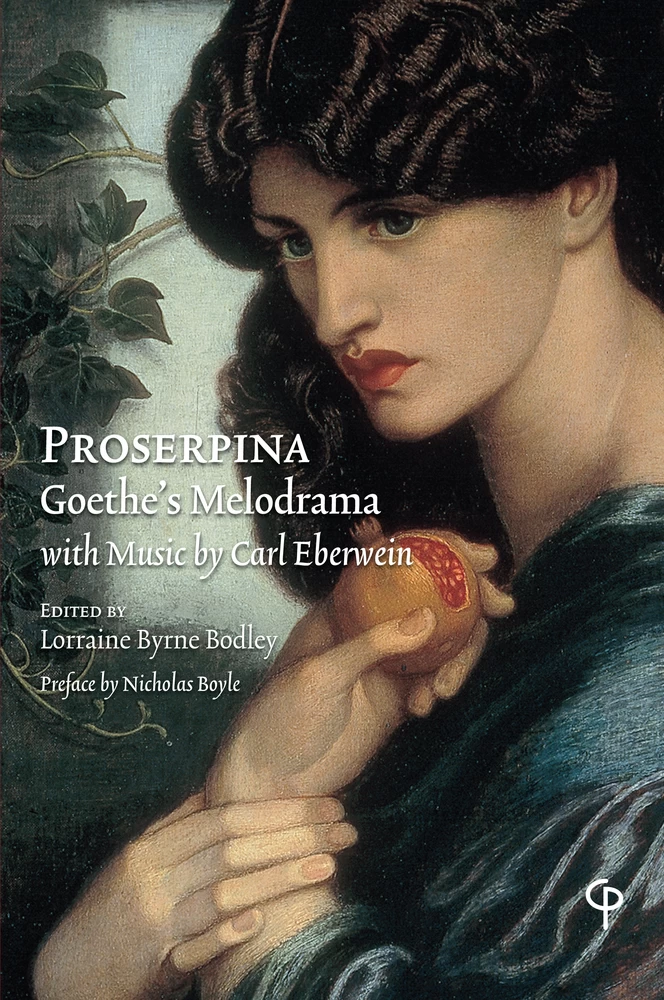

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Translator’s Preface

- 1 Introduction

- 2 The State Secret

- 3 Anna Amalia and Charlotte von Stein

- 4 Beginnings

- 5 Rise and Fall of a State Minister

- 6 Flight to Italy: ‘Oh, What an Error!’

- 7 Italy: ‘The Turning Point’

- 8 Tasso: ‘A Dangerous Undertaking’

- 9 Anna Amalia: An Outstanding Woman

- 10 David Heinrich Grave: A Human Catastrophe

- 11 Deception: Letters to ‘Frau von Stein’

- 12 Frau von Stein’s Literary Works

- 13 Love Poetry: Belonging to One Alone

- 14 Wilhelm Meister: ‘There is Life in It’

- 15 Epilogue: ‘All for Love’

- Bibliography

- Abbreviations

- Endnotes

- Index

Illustrations

Nos 1, 3-15, 17-20, 22-26, 28-33, 35, 37, 39, 40 by courtesy of Klassik Stiftung Weimar

Front Cover: by Bennis Design, using nos 18 and 19

1Anna Amalia. Oil painting by Georg M. Kraus 1774

2Anna Amalia as composer. Oil painting by Johann E. Heinsius, 1780. Repeat of a portrait from 1775/76. By courtesy of Denkena Verlag, Weimar

3Goethe in love. Oil painting by Georg M. Kraus, 1775/76. Commissioned by Anna Amalia

4Goethe. Artist unknown. Copied from Georg O. May, 1779

5Anna Amalia. Oil painting by Johann E. Heinsius, c.1779

6Goethe. Martin G. Klauer, 1780. From Anna Amalia’s Ettersburg forest residence

7Anna Amalia. Martin G. Klauer, c.1780. From Goethe’s garden house on the Ilm

8Anna Amalia in antique costume. Martin G. Klauer, 1780.

9Goethe in antique costume. Martin G. Klauer, 1778/79

10Garden of the Wittumspalais with Chinese Pavillion. Watercolour by Anna Amalia, c.1790

11Sedan chair in the Wittumspalais. c.1770

12Sketch of Weimar. By Johann F. Lossius, 1785

13Anna Amalia’s gondola

14Visit at the Villa d’Este. Watercolour by Georg Schütz and Anna Amalia, 1789. From left to right: Schütz, Herder, Anna Amalia, Göchhausen, Kaufmann, Reiffenstein, Einsiedel, Zucchi, Verschaffelt

15Rock formation forming the letters AA. Drawing by Goethe, c.1787

16Goethe in the Campagna di Roma. Oil painting by Johann H.W. Tischbein, 1786/87. By courtesy of Denkena Verlag, Weimar

17Anna Amalia in Pompeii at the tomb of the Priestess Mammia. Oil painting by Johann H.W. Tischbein, 1789

18Anna Amalia in Rome. Oil painting by Josef Rolletschek, 1928. Copy of the lost oil painting by Angelika Kaufmann, 1788/89

19Goethe in Rome. Oil painting by Angelika Kaufmann, 1787/88

20Evening entertainment chez Anna Amalia. Watercolour by Georg M. Kraus and Anna Amalia, c.1795. From left to right: Meyer, Wolfskeel, Goethe, Einsiedel, Anna Amalia, Elise Gore, Emilie Gore, Göchhausen, Herder

21The Igel column. Pen drawing by Goethe, 1792. By courtesy of Bildarchiv preussischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin

22Colour Pyramid. Made by Goethe, with note of appropriate qualities

23Extracts from letters, by courtesy of Goethe- und Schiller-Archiv, Weimar

24Charlotte von Stein. Drawing, artist unknown, copied from a self-portrait of 1787

25Medallion. Artist unknown, c.1785

26Goethe as Renunciant. Watercolour by Johann H. Meyer, 1795

27Anna Amalia as Renunciant. Oil painting by Johann F.A. Tischbein, 1795. By courtesy of Gleim Haus, Halberstadt

28Aqueduct. Shaped from the letters AMALIE. Watercolour by Goethe, 1806

29Lake in mountainous landscape. In front the letter A. Watercolour by Goethe, 1806

30Vignette, representing an A. Sketch drawn by Goethe, c.1807/10

31Vignette with Goethe. Drawn by Goethe, c.1807/10

32Anna Amalia as bride. Oil painting by Ferdinand Jagemann, 1806

33Goethe. Oil painting by Ferdinand Jagemann, 1806

34Death mask of Anna Amalia. By Carl G. Weißer, 1807. By courtesy of Goethe-Museum, Düsseldorf

35Mask of Goethe. The only one, made by Carl G. Weißer, 1807, in two sittings: on the first anniversary of Goethe’s marriage and on Anna Amalia’s first birthday after her death.

36Goethe. By Christian F. Tieck, 1807/1808. By courtesy of Walhalla, Donaustauf (photo: Robert Raith)

37Anna Amalia. By Christian F. Tieck, 1807/1808

38Goethe. By Carl G. Weißer, 1808. By courtesy of Goethe-Museum, Düsseldorf

39Anna Amalia. Carl G. Weißer, 1808

40Goethe. Oil painting by Ferdinand Jagemann, 1818

Translator’s Preface

Ettore Ghibellino’s J.W. Goethe and Anna Amalia: Eine Verbotene Liebe first attracted my interest as a book which contains, I think, a revolutionary hypothesis. The accepted opinion, namely, that Goethe’s platonic lover during the first decade of his life in Weimar was Charlotte von Stein, one of Anna Amalia’s ladies-in-waiting, is challenged in this book by the hypothesis that Goethe’s beloved was not Charlotte von Stein but the Dowager Duchess Anna Amalia herself. Naturally, this hypothesis which Ghibellino has set out to prove has caused consternation in some quarters. Since the publication of Goethe’s letters to Frau von Stein, scholars have generally accepted that Charlotte was the woman who inspired him to write much of his post-1775 love poetry and, in particular, the plays Iphigenie auf Tauris and Torquato Tasso. One of the main reasons given for his ‘escape’ to Italy in 1786 has been that he could no longer bear being kept at arm’s length by Charlotte, a married woman, and it has often been thought that, in his late thirties, he had his first full sexual experiences in Rome in the arms of an Italian widow.

Ghibellino claims that Charlotte von Stein was presented as Goethe’s (platonic) lover as part of a highly effective cover-up – designed, at first, by Goethe and Anna Amalia to protect their relationship from public view, and then by the Ducal family to protect its precarious position as a tiny Duchy at a time when Prussia and Austria strove to swallow up small, vulnerable principalities. The personal danger to both Goethe and Anna Amalia from a relationship which was not acceptable to the ruling European families was all too evident from the experience, in 1773, of the Queen of Denmark and her lover. When it was discovered that the Queen had given birth to a child fathered by her middle-class lover, the Queen was sent into exile and her lover was executed!

The need for a cover-up was apparent. The fact that there was, indeed, an official cover-up is suggested by the disappearance of all the documents from Weimar archives which could throw any light on the relationship between Goethe and Anna Amalia. When in 1827 the Grand Duke Carl August deputed Chancellor von Müller to put Anna Amalia’s papers and letters in order and to catalogue them, von Müller did this and showed the result to Goethe. Today there is no trace of the papers and letters. Not even the catalogue is to be found. Goethe’s own bequest was completely in the control of the Ducal family and shows clear traces of censorship.

One of the fascinating aspects of Ghibellino’s book is his thesis that many of the thousand letters that Goethe wrote to ‘Charlotte von Stein’ could not have been meant for her at all – for a variety of reasons. One of the most convincing of these reasons is that the addressee would, in some cases, need to have had considerable knowledge of Italian and Latin. These languages were not at all part of Charlotte’s education, whereas Anna Amalia had a thorough grounding in both of them. Ghibellino maintains that the loyal lady-in-waiting had become a conduit for letters which Goethe could not have addressed directly to the Dowager Duchess for fear of their love being discovered.

Ghibellino offers much more. Many questions arise from his interpretations of Tasso, Römische Elegien, Wilhelm Meister, the West-östlicher Divan, and Trilogie der Leidenschaft. Future studies will be dedicated to each of the problems he raises, and further serious research is being carried out to show that his hypothesis clarifies issues which heretofore have either not been clarified or not even identified. Documents unearthed in archives outside of Weimar have given strong indications that Goethe and Anna Amalia had a love relationship which they tried to conceal. Further archives – also outside of Weimar’s control – are being examined for more evidence to support the hypothesis.

A central claim of Ghibellino’s thesis is that Goethe’s creative writing also functions as autobiography. Dichtung und Wahrheit (Goethe’s autobiographical work written between 1811 and 1831) covers the years from his birth in Frankfurt am Main (1749) until the year of his arrival in Weimar in 1775. While he continued, after 1813, to write autobiographically about his Italian Journey – he was in Italy 1786-1788 – and about his time with Duke Carl August’s army in France around 1792, it has to be noted that these were periods he spent outside Weimar. There are no such autobiographical writings about his first Weimar period from November 1775 until his departure for Italy in September 1786. Ghibellino explains this by reference to the extreme danger that might result from an open description of his personal circumstances in Weimar. An important clue to the understanding of Goethe’s solution to this problem is his famous statement that all of his writings are fragments of an extensive confession. Ghibellino sees in this a hint – to be followed up – that for these years Goethe’s creative works are the substitute for open autobiographical writing, so that, for instance, the poems, the plays (Iphigenie and Tasso) and the Wilhelm Meister novels tell the story of his life in Weimar.

Naturally, this contention will require further examination and discussion. It is not Ghibellino’s aim to replace literary criticism and analysis with a study of the biographical elements included in the works, but this latter study is not invalidated by the fact that the works are literary. In other areas of research in which the sources of biographical detail are sparse – as is the case, for instance, with some mediaeval poets – scholars are confident that they can glean biographical (and social) information from the works of lyrical poets. This is also the experience of some art historians, who combine artistic analysis of paintings with a study of what the paintings yield up about the life and times of the painter. The term ‘biographical fallacy’ is to be handled with care.

Readers who are convinced by the evidence supporting Ghibellino’s hypothesis will see in it the discovery of one of the very great love stories in European history – to rank, for instance, with that of Dante and Beatrice, and Petrarch and Laura.

Alongside my role as translator I have, with the author’s consent, performed a modest editorial function. I trust that in this I have done the book no harm. My thanks are due to Ettore Ghibellino for his expansive generosity and willingness to help and advise. I admire his dedication to ferreting out the truth through his probing questions. The careful and thorough research evinced in the thirty-five pages of Ghibellino’s endnotes should earn his book an important place in the modern world of Goethe scholarship.1

My thanks are due to Ilse Nagelschmidt, who first drew my attention to the existence of Ghibellino’s book and who has been an inspiration every step of the way; to Lorraine Byrne Bodley for her many useful comments and suggestions regarding the translation itself; to Éimear O’Connor and Mary McAuliffe for advice on matters of art history and literary history; to Lilian Chambers of Carysfort Press for her eagle-eyed scrutiny of the manuscript; to Eamonn Jordan of Carysfort Press for his unflagging moral support; to Barbara Brown for the endless hours she spent, with great care and expertise, poring over the bibliography and the forest of scholarly endnotes; to Sheila Kreyszig for corrections of the manuscript and for useful suggestions regarding style and formatting.

Special thanks are due to my wife, Una, for her moral support and for the interest she takes in all I do. At times she is a miracle of tolerance. My daughters, Noreen and Ciara, and my son, Mark, give me – perhaps without realizing it – continual encouragement.

My thanks are due, finally, to the Ireland Literature Exchange for supporting Carysfort Press in commissioning this translation.

A last word: any errors which, despite the generous help I have received from various quarters, may still have crept into the manuscript, are my own, just as the entire translation, for good or ill, is also my own.

Dan Farrelly, Dublin, March 2007

1 One editorial note: the flawed language of the French quotations is not the responsibility of any living person, but is a reflection of the language as it was spoken and written at court in Germany around 1800.

1 |Introduction

Once error lies like a foundation under the ground

It will be built on, and never be seen in the light of day.

Xenien (c. 1796), 165

…in the sciences the most absolute freedom is necessary, for here we are not working for today and tomorrow but for a progressive series of ages beyond our grasp. But even if error gets the upper hand in science, there will still remain a minority favouring truth, and if truth withdraws into the mind of one single man, that does not matter. This one man will work away silently, in obscurity, and a time will come when people will ask about him and his convictions or when, in a more generally enlightened age, these views can dare to re-emerge.

Wilhelm Meisters Wanderjahre [Journeyman’s Years] (1829), III, 14

Innumerable works deal with the life of the poet Johann Wolfgang Goethe, attempting to interpret, explain, and understand his unique literary works. But more than 170 years after his death, and despite an undiminishingly intense preoccupation with his life and work, many noticeable contradictions remain. Why did Goethe remain in Weimar in 1775, and why, at the age of only twenty-six, was he appointed minister in the face of vigorous opposition? Why did he not marry and why instead did he choose to enter into an indefinable liaison with the married Frau von Stein? In 1786, why did he rush off to Italy and wait for weeks in the port of Venice? On his return from Italy, why did he take Christiane Vulpius for a lover, although he did not treat her as a social equal; and why did he not marry her for nearly two decades, even though his son thereby grew up as a bastard? In his writings, why does the theme of a forbidden love for a highly placed, unattainable woman constantly recur? Why does Goethe’s love poetry give witness to the profoundest feeling of love for ‘a unique one’, although he is ←1 | 2→supposed to have had only superficial relationships with many women?

These and other contradictions can be explained if we suppose that Goethe loved the Duchess Anna Amalia and remained true to her until the end of his life. Since this love was forbidden, it had to be concealed. But the lovers were still able to communicate their tragic love story to the world. They had to do it in code, which must be the reason why for most of his life Goethe had recourse to ‘the enigmatic, to ciphers, hermetic formulas, masks, disguises, and encoding’.1

Since this book [the German original] first appeared, the question has often been asked: ‘Why did no one until now know about Goethe’s love relationship with Anna Amalia?’2 The main reason for this is that in the Duchy of Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach it was treated as a state secret. From 1786 onwards, all the Dukes used every means at their disposal to suppress all documents referring to Goethe’s secret love for the Princess Anna Amalia. The basis of Goethe research was subject to the massive influence of the family of Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach. The Dukes could manipulate the archives however they wished. It was known amongst researchers that ‘the Weimar archive … had more seals and locks than any other’ (1858).3 Researchers knew exactly where crucial documents were kept: ‘Much and perhaps the most important [material] is not in the archive at all, but in the private library of the Grand Duke’ (1857).4 Even when crucial documents were not in the Grand Duke’s possession, there were ways and means of preventing their publication. This is evidenced by the case of the heiress of Carl Ludwig von Knebel, Goethe’s close friend. When selling manuscripts contained in Knebel’s bequest in 1864, she warned the agent entrusted with the transaction to examine the contents most thoroughly and search for utterances which could compromise the family von Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach, since ‘her whole livelihood would be endangered for the slightest thing that might come to light’. When he married Luise Rudorff (1798) Knebel adopted her illegitimate son (1796), a child of Carl August. The ‘diary from the “eventful year 1798”’ is missing down to this day.5

All but a few of Anna Amalia’s letters to Goethe and to her son Carl August are considered lost. When Carl August entrusted Anna Amalia’s letters and papers to Chancellor von Müller, requiring him to look through and catalogue them, von Müller reported with enthusiasm that these would throw ‘a glorious light on the character of Goethe and the Duchess!’6 When shown the first results of von Müller’s work, Goethe wrote to him on 24 July 1828:

It is a great joy to me to know that this work, which has to be carried out with insight and loyalty as well as caution and taste, is in your ←2 | 3→hands. In this way very special documents will be rescued; [they are] priceless, not from a political but from a human point of view, because only these papers will give a proper insight into the way things were at the time.

These papers have disappeared without trace. When what was left of Anna Amalia’s letters was, from 1872, carefully sifted through, the ruling Grand Duke insisted on a two-fold right: to correct and to supervise in the case of any publication – which, however, was not to come about.7

Until now it has been impossible to explain why Goethe’s grandchildren, for more than half a century and for no apparent reason, refused access to his bequest to researchers, writers, and publishers, most of them ardent admirers of Goethe. ‘They have been warned, scolded, spurned because they did not open the way to the temple’s treasures.’8 From childhood onwards Goethe’s heirs were tied to the family Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach. They were treated generously and shown good-will. In response the Ducal family expected that documents in the bequest which could have revealed his forbidden love for Anna Amalia would not become public. The sale negotiations in 1884 between Goethe’s grandson Walther Wolfgang (1818-1885) and the German Reich regarding the sale of Goethe’s bequest show, for example, that the reigning Grand Duke took it for granted that he had wide-ranging claims over the bequest. He made it a condition of the sale

that nothing of it will ever be published without my express knowledge and permission. If this [directive] is not observed I would use every means in my power – including Emperor and Empress – to prevent the transaction with the Reich.9

Details

- Pages

- XVI, 342

- Publication Year

- 2007

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781789971217

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781789971224

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781789971231

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781789971248

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2020 (April)

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, New York, Wien, 2007. XVI, 342 pp., 3 fig. b/w

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG