Challenging Voices

Music Making with Children Excluded from School

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Chapter 1 Introduction

- Chapter 2 Who gets excluded?

- Chapter 3 Theoretical underpinnings

- Chapter 4 The history of education with ‘maladjusted’ children

- Chapter 5 Pupil referral units

- Chapter 6 What the children bring

- Chapter 7 The relationship between children and adults

- Chapter 8 Behaviour management

- Chapter 9 What music can do

- Chapter 10 Musical ideas and leadership

- Chapter 11 Energy, focus, flow and change

- Chapter 12 Intent

- Chapter 13 Developing reflection

- Chapter 14 Practioners

- Chapter 15 Summary and conclusion

- Bibliography

- Glossary of terms and acronyms

- Index

Tables

Table 1.

Risk factors for permanent exclusion (Pitchford (2006). Cited in Arnold et al. 2009: 19)

Table 2.

Elements of emotional intelligence (Goleman 1998: 26–7)

Chapter 1

Introduction

Why I wrote this book

In 2009 I was working as an inclusion advisor for the English national primary age singing programme Sing Up. This was, at the time, a well-resourced programme that aimed to get every child of primary school age singing regularly. Much of the early work of Sing Up was in mainstream primary schools but I was involved in an initiative called Beyond the Mainstream that was about engaging children who could not easily access singing in mainstream schools. This included children in special education, children who did not live with their parents (called looked after children or children in care), refugee children, children with mental health problems and others.

One group that was high on our agenda was children who had been excluded or could not be in mainstream school, who were now in what was called alternative provision (AP). Alternative provision consisted of a number of different ways of supporting these children. Two of the better-known ones were pupil referral units (PRUs as they will be called throughout this book) and emotional and behavioural difficulty (EBD) units. There are other types of alternative provision but these are the best known.

I became involved as a Sing Up Ambassador to PRUs and began visiting and leading voice and creative sessions in them. During my time with Sing Up I visited perhaps forty primary age PRUs and got a real sense of what went on in them and what the children were like who went there. The regimes were all different from each other. I immediately got attached to the children. They were in the main funny, interesting young people, who, although few of them had high levels of self-esteem or skill, did have ←1 | 2→a go and showed commitment to getting involved in music. Many did have challenging behaviour but almost all were able to moderate that behaviour during any music work we did together. As I researched these units I realized that the children in them often had terrible life outcomes, and, although they were only a small group, many of them went on to become homeless, get involved in criminal activity and have an existence at the very lowest levels of society. Given what I saw of their musical and personal potential I felt this was very unfair on them. I saw the issues that caused their poor outcomes as systemic, rather than the fault of individual PRUs, heads of units or teachers.

When I started working in PRUs I began by using what I would call a community music methodology, derived from my training in the growing field of community music and my, at that time, twenty-five years practice in the field. I led training for PRU staff and freelance music leaders in how to work with these children using this methodology and this book focuses on a community music approach to music in PRUs.

Once I got a chance to pursue a PhD I immediately decided it should be about music making with children with challenging behaviour who were excluded from school and in PRUs and to a lesser extent EBD units. This book has grown out of my PhD studies, my work in PRUs and some refresher research I have done since.

I believe, and it is the main contention of this book, that regular participation in music making, in what I call appropriate ways, can be vital not only for these children’s musical development but also their sense of self, their confidence and personal growth as well as their ability to be with and achieve with other children. I believe that music can be a source of transformation for children in PRUs and this book tries to explain that process of potential transformation. I also believe that funders and policy makers should take notice of the results of the music work that is happening in alternative provision and substantially increase support for this sector.

What is in the book?

This book has developed from several strands of my research into approaches to music work in PRUs. I reviewed the literature, observed music work in twenty-two PRU and EBD Units, interviewed a number of mostly non-music specialist PRU staff, and also had interviews and focus groups with music leaders working in alternative provision. At a later stage I followed up this research with in-depth interviews with thirty-five music leaders working mostly in England, but also in Canada, the USA and Switzerland. While those music leaders worked in different systems, the children and the issues were very much the same.

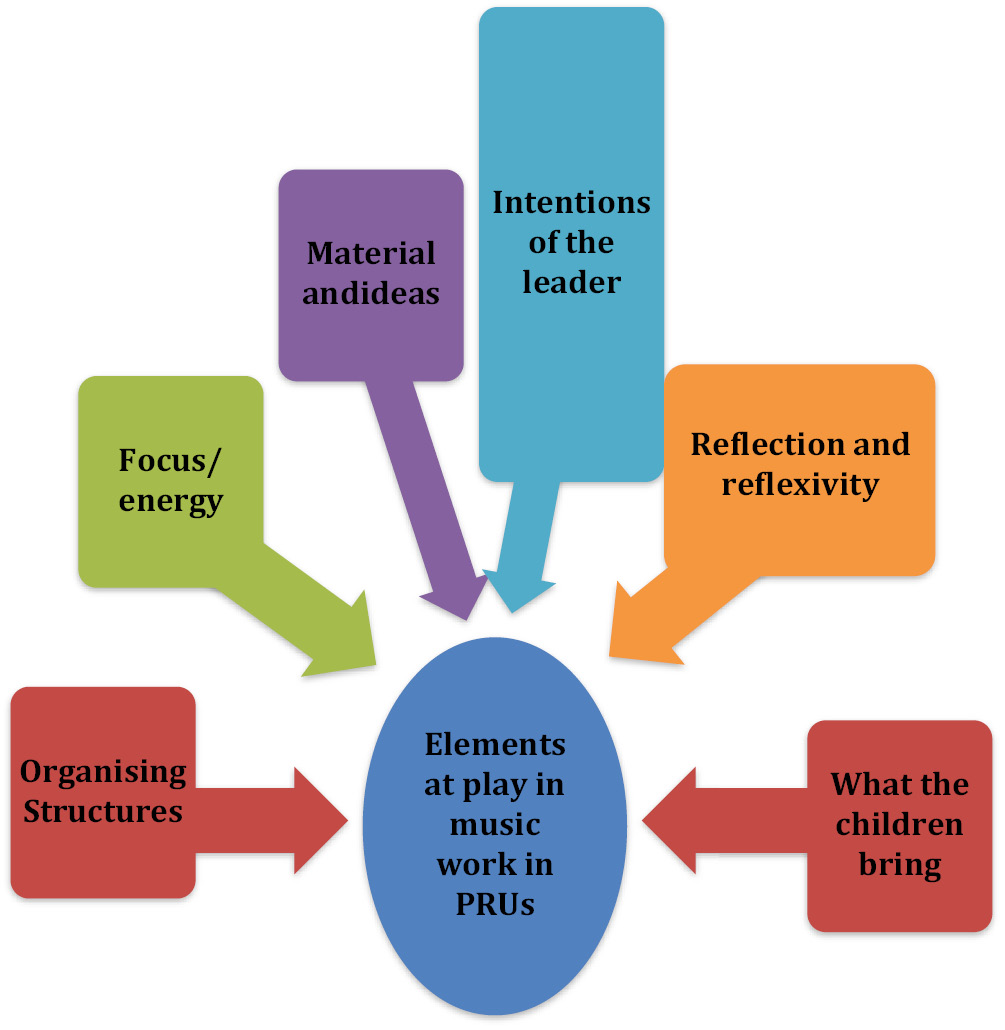

During my PhD research, it gradually emerged that a number of elements of practice were in dynamic interaction with each other and that each needed to be understood and optimized to achieve a successful music programme.

These elements (outlined in Figure 1) were continually shifting in a non-hierarchical relationship with each other, feeding off each other to the good or ill of the session. On any given day, one element might be more important than the others in helping the session succeed or fail. For example, if ‘what the children brought’ was a restlessness or distress, this could dictate the nature of the session including what would be useful ‘ideas and material’ for that day or how to work with the ‘focus and energy’ of the group. Conversely, if the children brought a relaxed openness this would dictate a different shape to the session and affect all the other elements in turn.

In writing for the book, I decided to disperse the findings of ‘organizing structures’ across several chapters, notably Chapters 4, 5 and 8. ‘Ideas and materials’ has been renamed ‘Musical ideas and leadership’. Each of the other elements has its own chapter and I summarize what is in the chapters below.

In Chapter 2 ‘Who gets excluded?’ the focus is on who exhibits challenging behaviour and who gets excluded from school, their socio-economic circumstances, gender, ethnicity and a range of other factors that mean that children in particular circumstances are much more likely to be excluded than any others. It looks at the life journeys of these children, how they underachieve academically and throughout life and how many of them lead a life of heightened risk.

Chapter 3 looks at community music and the ideas behind it. It also a short look at theories from social science including self-determination ←4 | 5→theory, a brief look at the ideas of Lev Vygotsky and Carl Rogers in education and theories around power in society, most notably those of Foucault and Bourdieu.

There has been 200 years of education in the UK for children who are at risk of becoming criminals. Chapter 4 ‘The history of education with “maladjusted” children’ looks at this history, what has changed about labelling and intervention approaches and what has remained the same. It looks at how education of this group has been undervalued and poorly resourced and draws parallels with the treatment of these children today.

Chapter 5 examines the structure of pupil referral units (PRUs) and the issues within them such as (often) unsuitable buildings and lack of resources as well as high staff turnover.

Chapter 6 highlights and values what the children themselves bring to the music session, whether that is their own challenges, their challenging behaviour and their differing abilities or it is their interests, their ideas and their passions. It goes on to talk about how music leaders and teachers can use what the children bring to create an engaging and productive music programme.

Taking its ideas in large part from the field of childhood studies, Chapter 7 discusses the changing views of childhood and children held by adults at different times and in different places. The second part of the chapter is based on recent interviews with musicians working with children with challenging behaviour and examines the very different ways they look at the relationship they have with those children.

Chapter 8 looks at the marked difference in responses to behaviour between non-music specialists and music leaders in PRUs.

Drawing on research collated by Susan Hallam and others, Chapter 9 looks into the change-making aspects of music participation; particularly what music can do to build resilience, personal growth and a more confident social self.

Chapter 10 ‘Musical ideas and leadership’ is an extended chapter that analyses what in both music and pedagogical approaches can work best with these children to enable them to progress musically, personally and socially. It deals in detail with repertoire, creativity and the role of the leader/facilitator.

←5 | 6→Chapter 11 looks at what happens in a group when the energy flow rises, whether it becomes out of control and descends into chaos or whether it can lead, through an attention to focus, to greater musical achievement and potential transformation. The chapter goes on to look at the concept of flow in music and also focuses on how to create conditions for personal transformation through music.

Working with children with challenging behaviour, the leader’s intention for the group or for individuals in the group may change from session to session or even several times within a session. Chapter 12 examines the leader’s intent and is based around the idea that in community music practice there are three broad areas of intention for music leaders: music development, personal development and social development (Lonie 2013; Deane et al. 2014). Building on these areas the chapter will look into the complex nature of leader intention in this work and how intentions might link to practice. The chapter also notes how music leaders’ intentions may differ from and have potential conflict with the regimes in which the children spend their time.

Chapter 13 looks at both reflective and reflexive practice and emphasizes the importance of structured approaches to reflection. It gives a number of ways to structure reflection both as an individual and as part of a team.

Chapter 14 features an interview with community musician Graham Dowdall, who has considerable experience working with children with challenging behaviour in a range of contexts. It also contains an interview with Simon Glenister, the founder of Noise Solution, an organization that uses music technology to work with marginalized teenagers and young adults.

The final concluding chapter brings together the key findings and argument of the book.

What is community music and what is its place in this book?

When I talk above about participation in music for the children in PRUs, I say it should be in ‘appropriate ways’. I have noticed in my research that ←6 | 7→many of the music leaders in PRUs call themselves community musicians and use a community music methodology. Those music leaders I spoke with who came from a more established or traditional music education training, and who often (unlike the community musicians) had qualified teacher status (QTS), described parts of their practice that were clearly resonant of community music principles and practice. In every way that they adapted their practice, it more and more resembled community music practice, although they were still, understandably, committed to working within the national curriculum and working towards national tests if at all possible with their students. Community music leaders were not concerned with the national curriculum or any form of national testing.

Community music is notoriously difficult to define and has no internationally agreed definition at time of writing (Veblen 2010: 51). In fact different countries sometimes have different models and understandings of the term (Veblen 2002; Elliott et al. 2008). As practised in England, there is a certain unity to the work and those in the field recognize the commonalities in their practice, even if they sometimes find it hard to articulate them. For my part I would define community music in England as:

Details

- Pages

- XII, 280

- Publication Year

- 2022

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781800791282

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781800791299

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781800791305

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781800791275

- DOI

- 10.3726/b18617

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2021 (December)

- Keywords

- Inclusive music education Music with young people with challenging behaviour Community Music Phil Mullen Challenging Voices

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, New York, Wien, 2022. XII, 280 pp., 2 fig. col., 2 tables.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG