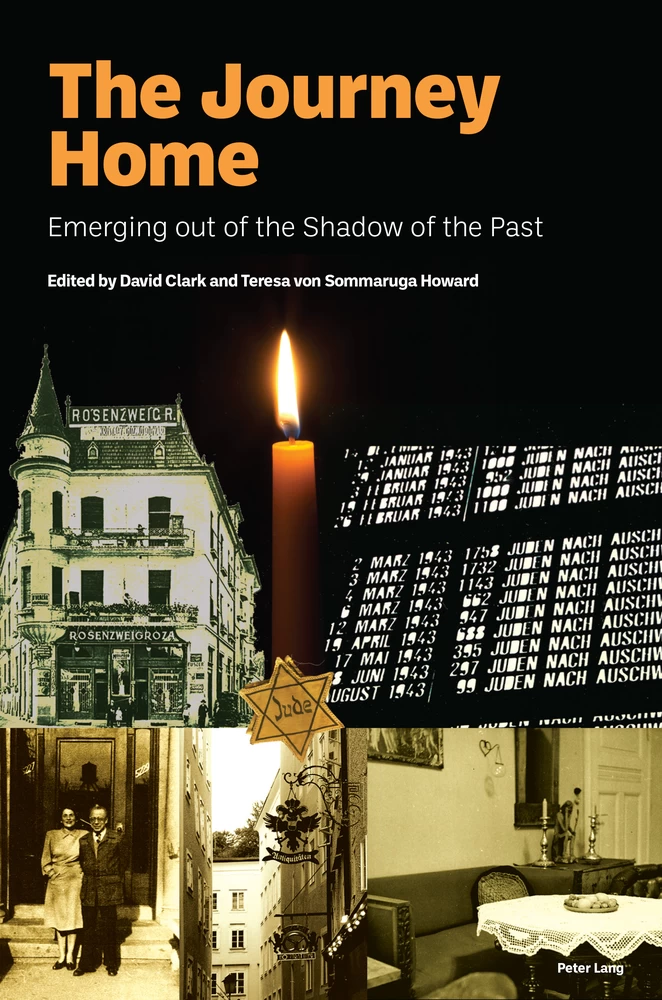

The Journey Home

Emerging out of the Shadow of the Past

Summary

Some of these journeys are undertaken with a parent. Others are undertaken with friends or partners and some venture back alone. Along the way, new connections are forged with the living and with the dead, with the past and with the present.

Together with an introduction and epilogue, the book provides not only examples of the lived experience of being «second generation» but also offers some theoretical background to the stories and relates them to current and important themes, such as the role of acknowledgement, memorialization and commemoration. With eighty million people around the world currently displaced by disaster, war and famine, many of these stories speak for descendants of refugees and survivors of all such catastrophes.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the editors

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures

- Foreword: Home is where the heart is (Judith Tydor Baumel-Schwartz)

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- List of abbreviations

- A note on the text

- Introduction (David Clark and Teresa von Sommaruga Howard)

- Part I Journeys with a survivor or refugee parent

- 1 ‘Heimish’ at last (Janet Eisenstein)

- 2 Kraków:: A visit with my mother to her hometown (Naomi Levy)

- 3 Lost in transportation (Tina Kennedy)

- 4 Faraway country, faraway time? (Vivienne Cato)

- 5 Living with humiliation: Reflections on a trip to Berlin with my father (Teresa von Sommaruga Howard)

- 6 Mein shtetele Turek (Elaine Sinclair)

- 7 The only house that was built for me (Diti Ronen)

- Part II Journeys without a survivor or refugee parent

- 8 Terežin 2000 (Rosemary Schonfeld)

- 9 Exploring German Jewish roots in Berlin (Marian Liebmann)

- 10 Letter from Bratislava: 1976 (Vivian Hassan-Lambert)

- 11 The dawn of realization (Oliver Hoffmann)

- 12 Into the stream of history (Diana Wichtel)

- 13 Shards of the past (Zuzana Crouch)

- 14 : Black milk and word light: To Latvia, Siberia and back (Monica Lowenberg)

- 15 Only a two-hour flight, but it took me forty-seven years to get here! (Barbara Dresner)

- Part III Journeys undertaken for commemorative events

- 16 ‘Opening doors’ (Merilyn Moos)

- 17 I joined the dots and the dots joined me (Nik Pollinger/Pöllinger)

- 18 Haunted, or at home? (Gina Burgess Winning)

- 19 Three unexpected ceremonies (Peter Bohm)

- 20 Compass points in a nomadic life (David Clark)

- Epilogue (Teresa von Sommaruga Howard)

- Notes on contributors

- Index

Figures

Figure 0.1.Stolpersteine in Berlin (Photo taken by Teresa von Sommaruga Howard).

Figure 1.1.Eva as a child, with her father (From family collection).

Figure 1.2.Janet’s mother, Eva, at the Berlin Holocaust Memorial (Photo taken by Janet Eisenstein).

Figure 3.1Tina with her father (Photo taken by Tina’s husband Richard Dennison).

Figure 5.3.Teresa with her father on her wedding day in December 1963 (From family collection).

Figure 7.2.A page from Safta Pipike’s corset catalogue (From family collection).

Figure 9.1.Marian’s mother’s apartment building, Berlin, in 1977 (Photo taken by Marian Liebmann).

←xi | xii→Figure 10.1.Vivian in Slovak costume (From family collection).

Figure 10.2.Vivian with her mother (From family collection).

Figure 11.1.Oliver’s booklet on the Tiergarten district (Provided by Oliver Hoffmann).

Figure 11.2.Stolperstein for Oliver’s grandfather (Photo taken by Oliver Hoffmann).

Figure 12.1.Diana’s father in 1947 (From family collection).

Figure 15.1.Front cover of Rolf Dresner’s Polish passport (From family collection).

Figure 15.2.Inside page of Rolf Dresner’s Polish passport (From family collection).

←xii | xiii→Figure 17.1.Nik standing in front of his family’s old shop in Gmünd (From family collection).

Figure 17.2.Poster in Gmünd announcing book launch (Photo taken by Nik Pollinger/Pöllinger).

Figure 17.3.Three-year-old Nik in Lederhosen in an Alpine setting (From family collection).

Figure 19.1.Plaques in Vienna commemorating Peter’s grandparents (Photo taken by Peter Bohm).

Figure 19.2.Plaques in Amersfoort on the day of the commemoration (Photo taken by Peter Bohm).

Figure 19.3.Children cleaning Stolpersteine (Photo taken by Janet Eisenstein).

Figure 20.2.David with grandfather, Siegmund (Photo taken by Grete Weltlinger).

Foreword: Home is where the heart is

One of the more popular songs of my youth was a ballad by American singer and songwriter, John Denver, entitled Take Me Home, Country Roads, that spoke about the yearning to return “to the place I belong”. Reading The Journey Home brings me back to those days and the special memories I had of that song. Denver’s sentiments may have been directed towards West Virginia and not Western Galicia where my survivor father had been born, but the feeling was similar. A desire to see one’s home, a yearning to belong, a longing for a sense of roots. The home may have never been mine, the belonging was to people and families long destroyed and the roots were deeply set in soil I had never stepped on. But the longing was there, nonetheless.

“Never get attached to any object or place in case it keeps you from escaping on time”, was my mother’s credo, and it took its place of honour in my psyche as a member of the second generation. In my case, it was strengthened by being raised on stories of Jews who were swallowed up by the Nazi maw as they had been emotionally unable to tear themselves away from their homes\marriage beds\familiar streets on time, in order to run. Cut your geographical and material ties so you can get out faster. Don’t make them in the first place so that they won’t slow you down. Those were the messages that we were given so that we would have a head start, “the next time around”.

Whether voiced openly, as it had been in my childhood home, or just alluded to by suggestion, members of the second generation brought up with those sentiments often found it difficult to become attached to any of the places where they lived, always remembering stories – heard or imagined – of how their parents were torn from their homes, whether by fleeing on their own or being dragged away by the Nazis and their accomplices. As a result, many felt a sense of rootlessness, or a deep-seated feeling of not really belonging, a common thread heard among members of the second generation when evaluating their lives. Echoes of that feeling appear ←xv | xvi→throughout this volume where members of that generation describe what for many became a (lifelong) journey back to their parents’ former homes in order to find what they were missing.

How is the desire to see one’s parents’ home connected to a sense of roots? After all, decades had passed. Did these second-generation members not have roots of their own by now, deeply fixed in their own country of birth? Some obviously did, but others still felt themselves in need of a geographical anchor, hoping to close a circle by being able to stand on the same soil where their parents had been born, studied, prayed or played, creating a personal paraphrase of Genesis 3:19, “For you are dust and to dust you shall return”.

One group of second-generation members made the trip together with their survivor or former refugee parents. Others went after their parents’ death. Those with elderly parents, unable to travel, went without them but often communicated to them how they had retraced their family history. Some undertook the journey to help them come to terms with the burden of the past. Others saw it as part of the grieving process for a lost world and family that they would never know.

I undertook such a journey over a third of a century ago, in the days when Poland was still semi-communist, the Berlin wall had not yet fallen and luxury items such as good vodka or imported oranges could only be bought in the State-run Pewex stores with foreign currency, preferably dollars. I had asked my father, an Auschwitz and Buchenwald survivor who was then an active and healthy man in his mid-80s, whether he wanted to join me, but he refused to even consider the possibility. He did, however, give me the address of his former home in Bochnia, where he had been born and lived throughout his childhood, right near the area of the Bochnia Ghetto where his father, sister and first wife had either been shot or from where they were sent on their final journey.

In early 1988 I found myself standing in front of that house in the dead of night, having convinced the Polish bus driver of the group I was leading to make a detour off the main road to Krakow in order to search for a particular house on a particular street, “off to the top left of the Rynek (town square)” as my father had directed. It was more than a decade before the first mobile phone with a camera would become available and the word “selfie” ←xvi | xvii→would become part of our lexicon, and so a member of the group gladly offered to take a picture of me in front of the long one-storey building as a memento of that midnight visit. The street was deserted, the house locked. My only real memory was looking at the side of the house and seeing the apple tree that my father had described being outside his bedroom window. When I returned home my father showed definite interest in the picture, but little connection to the town. He had put it far behind him, living very much in the present and not in his distant the past.

Six months later I was back there again, leading another group, this time in the daylight. Again, I took a picture of the building but did not make any effort to enter. It was only in 2007 when I came to Poland on a belated honeymoon and took my husband to see where his late father-in-law had been born and raised, that our private guide knocked at the door and asked the tenants if they would allow us to look around. Despite the decades that had passed since the war, the house looked much like my father had described it with the big surprise being the enormous garden on a large plot of land behind the house. For the first time I could picture my family as it had been while living there, a well-to-do strictly Orthodox Jewish family. Visiting the local archive, I found the original deed to the house and listings of my father’s birth, his parents’ marriage and that of his grandparents as well. Continuing further up the winding street I came to the area of the former ghetto and newly dedicated memorial for the town’s Jews murdered during the Holocaust.

This was indeed the journey of a member of the second generation in search of her roots. A journey to close a circle and get a glimpse of my origins. None of the locals whom I came across on that visit had any connection to my family, but I wondered whether their parents or grandparents had ever come across mine and if so, when and in what capacity. Some things are better not thought about.

A number of second-generation members journey to their parents’ former homes to participate in a memorial ceremony, affix a plaque or a memorial stone to a building or a sidewalk. I did none of the kind, but at my visit to the Bochnia Holocaust Memorial, I laid a small stone next to the marker in the same fashion that Jews leave a rock on a tombstone to show that someone has been there, that someone remembers.←xvii | xviii→

And maybe, in addition to closing circles and looking for roots, journeys of second-generation members to their parents’ former homes are a way of figuratively laying that stone, showing that someone still cares and remembers. “To be unremembered is to die a second death”, writes Rabbi Theodore Friedman in an essay entitled Do you Remember? And so, these visits are actually an affirmation of life, having transmitted the onus of remembrance to a new generation.

Judith Tydor Baumel-Schwartz

Details

- Pages

- XXXII, 308

- Publication Year

- 2022

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781800795815

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781800795822

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781800795839

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781800795808

- DOI

- 10.3726/b18627

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2021 (December)

- Keywords

- Second Generation and the aftermath of the Holocaust socio-political trauma travels connected with family history personal and collective memory at commemorative events (150) The Journey Home David Clark Teresa von Sommaruga Howard Holocaust

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, New York, Wien, 2022. XXXII, 308 pp., 36 fig. b/w.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG