Visions of Europe in the Resistance

Figures, Projects, Networks, Ideals

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the editors

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- Introduction (Robert Belot and Daniela Preda)

- Part 1 The European idea in the national Resistances

- Above Hatred and beyond Borders: The French Resistance’s gradual realization of the need to make Europe (Robert Belot)

- The idea of Europe in the German Resistance (Wilfried Loth)

- Visions de l’Europe d’après-guerre par la Résistance en Belgique et aux Pays-Bas occupés 1939–1945 (Thierry Grosbois)

- The European Federalist network in Switzerland during World War II (Francesca Pozzoli)

- La Résistance de la Rose blanche et l’Europe (Umberto Lodovici)

- Ursula Hirschmann: a European federalist with no homeland (Silvana Boccanfuso)

- The Kreisauer Kreis’ plans for Europe (Stefano Dell’Acqua)

- Alexandre Marc’s battle for a new order. French Fédératisme on the eve of European federalism (1928–1942) (Catherine Préviti)

- Part 2 The European idea in the Italian Resistance

- The Partito d’Azione’s idea of Europe (Andrea Becherucci)

- The national liberation struggle and the idea of Europe in Italian catholic circles (Giovanni Battista Varnier)

- The idea of Europe among the Republicans (Maurizio Ridolfi)

- The Italian liberal Europeanists and the vision of a federal Europe (Umberto Morelli)

- The idea of Europe in the Italian Resistance: the birth of the movements for European unity (Sergio Pistone)

- The words of Ventotene. A historical-critical analysis of the Ventotene Manifesto (Antonella Braga)

- Italian military in the war of Resistance in Yugoslavia after the 8September 1943 armistice (Maria Teresa Giusti)

- European unity in the underground press of the Italian Resistance (Raffaella Cinquanta)

- Part 3 The European idea among the exiles

- Silvio Trentin’s idea of Europe in the Resistance movement in France and Italy (1940–1944) (Corrado Malandrino)

- Rossi, Spinelli and the idea of Europe among Italian refugees in Switzerland (Alfredo Canavero)

- Hilda Monte and the unity of Europe. Resistance, solidarity and planning in exile, 1933–1945 (Andreas Wilkens)

- Un projet d’Europe centrale conçu à Londres entre diplomates et militaires polonais et tchécoslovaques : les origines d’un échec, 1940–1941 (Lubor Jílek)

- Visions of post-war Europe. A European in America: Richard Count Coudenhove-Kalergi in exile (Martyn Bond)

- Jean Monnet’s network in the United States (Maria Eleonora Guasconi)

- L’Europe et le fédéralisme vus du côté des antifascistes européens en Amérique latine (années 1930 et 1940) (Jean-Francis Billion)

- Part 4 The European idea in the Resistance: transnational aspects

- Ecumenism, Resistance, European unity and international relations: a convergence between Willem A. Visser ’t Hooft and John Foster Dulles (Filippo Maria Giordano)

- The Geneva meetings and the international federalist declaration of the European Resistance movements (Paolo Caraffini)

- The Resistance in the Alpine World and the Chivasso Charter (Fabio Zucca)

- European constitutional projects during WorldWarII and the immediate post-war period (Daniela Preda)

- Series index

Introduction

In the 20th century, Europe experienced the worst (fascism, Nazism, dictatorship, communism, ethnic conflict). It also dreamed of the best (union, peace, democracy, solidarity, respect for humans) and partly achieved it through what is called “European construction”. We sometimes tend to forget that the unification of Europe after 1945 was an incredible political creation like no other and a geopolitical and symbolic act of the utmost importance.

Post-war Europe was essentially built on the rejection and overcoming of a traumatic history that had led to the denial of its humanist values and its moral and political weakening. It had to guard against the risks of a return to nationalism and xenophobia; it had to be the binding force through which European sentiment would develop to forge a European citizenship.

Recent events (such as Brexit) show us that the hard-won unity of Europe is not as irreversible as we had hoped. The development of national-populism, in both Western and Eastern Europe, reminds us that awareness of this historic achievement is not shared as unanimously as one might have imagined. Crises engender euroscepticism, even europhobia, which sometimes attacks the axiological and metapolitical foundations that support the European project and which were thought to be beyond reach. The myth of the “decline” of Europe feeds on the legendary nationalist that produces a kind of (illusory) identity reassurance effect in the face of change. It homogenizes reality in order to valorize an imaginary community of belonging. Today, a nationalist counter-narrative is developing that presupposes the substantiality of the nation to oppose it to the artificiality of Europe in order to delegitimize the European project. A revisionist and conspiracyist memory frees itself ←11 | 12→from the historiographical achievements and calls into question a heritage that was supposed to show the way to a better future.

At the origin of this book and the colloquium that preceded it, there was a question: The current memory deviances, flourishing on the poisonous soil of instrumentalized fears, could be analysed as a perverse effect of this difficulty in understanding and knowing the history of Europe? The crisis of European consciousness is also a crisis of consciousness and historical knowledge of Europe.

In fact, the question of the achievements of European construction and the very idea of Europe develops from a faulty and untimely rereading of history. One seeks to undermine the honorability of the pioneers of this history but also the sincerity and importance of the goals that Europe was supposed to pursue, after the tragedy of Nazism and the war that had covered it with ruins and shame. This rereading proceeds from a revisionist approach that selects the elements of this very complex history in order to reduce it to a manipulation of the American government and a “liberal conspiracy”. It isolates and demonizes figures such as Jean Monnet, Robert Schuman, or Alcide de Gasperi, in order to reduce the European project to the effect of the hegemony of the United States during the Cold War. The new “fathers of Europe” would be John Foster Dulles and George Kennan! Without wishing to take anything away from the importance of the influence exercised by the United States, and in particular by the Marshall Plan, on the start of the process of European unification, it is not possible to remain silent on how historiography has long been subjected to a flat interpretation that made Europeanism and Atlanticism coincide, failing to read and interpret the birth within the bipolar world of a new subject: a united Europe.

This thesis is not new. It was the dominant doxa of the French communists in the aftermath of the World War II, when they dominated the political and intellectual field and presented themselves as the spearhead of anti-Americanism and “anti-imperialism”. What is new is that the hunt for “European supranationalist ideology” is being taken up today by the proponents of an anti-Europeanism thriving in the radical right and the national-populist movement. The communists had not foreseen such heirs.

Another myth since the 1990s is the myth of Europe’s “impure” sources. A sub-literature plays on biased and falsified historical analogies ←12 | 13→to delegitimize the philosophical roots of the European project. With the “return of Germany” after reunification, there is an awakening of the fear of the old demons of Germanism. The “extreme eurosceptic” discourse boasts comparisons with the Holy Roman Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire or Hitler’s Germany, against a background of more or less declared but profound anti-Germanism. The thesis was first spread in the romantic mode, with Andrew Roberts’ book: The Aachen Memorandum (1995). A futuristic and dystopian narrative, which describes the Great Britain of 2045 as a satrapy of a new “totalitarian German-European” Reich. The author imagines a British “Resistance” movement against the new Nazi regime that the European Union would have recreated! There is, of course, something shocking in these pointless comparisons, which confuse democracy with Nazism, leading, in the end, to relativizing the absolute horror that Nazism and the Shoah were in the heart of Europe.

This revisionist logic leads to a kind of desecration of the ideal represented by the anti-Nazi and antifascist Resistance. It is a contempt for those who fought, at the risk of their lives, for this ideal. It is also a way of diminishing the major event that was the victory of the Allies, that is to say, the fight for the reconquest of democracy and freedom in Europe. Thus, we move from relativization to revisionism by questioning the achievements of this unprecedented struggle against horror and the worst.

Contempt for history is thus combined with contempt for historians and academics in general, even if some of them are sometimes used as a guarantee. The historians of Europe would be suspect. Especially those who hold a European Jean Monnet Chair, like the two directors of this publication. We believe that there is an urgent need to develop the history of Europe in European higher education in order to train minds that will have the capacity and lucidity to detect the traps of the manipulators of history and the conspiracy theorists. It is not a question of teaching a “holy history” but a critical history. It is about moving from opinion or prejudice to knowledge. For one of Europe’s distinctive values is this capacity to distance and criticize oneself. In the face of the enterprises of “disrecognition” of European history, promoted by the ideologues of anti-Europe, it is a question of trying to know what makes up the history and identity of Europe.

It was therefore necessary to react. We have to remind people where Europe comes from. This book tends precisely to recall that the idea of a ←13 | 14→united Europe, reconciled with democracy, was a fundamental achievement of the Resistance of Europeans against Nazi-fascist domination. The fight of the Resistance was not only military, it was a project of political revolution. As the title of the movement Libérer et Fédérer, on July14, 1942, it was about “Winning the war and winning peace”, that is, proposing a new mode of governance between European nations that emancipated themselves from the dogma of the absolute sovereignty of states and its belligerent potential.

The participation to the Resistance during the World War II created in some enlightened individuals and little groups a new feeling of belonging that overstepped the traditional borders of the State in the knowledge of a common destiny for all the European peoples, i.e. in a moment in which the struggle against the tyranny didn’t have any barrier. Men and women in the occupied countries – engaged side by side in the common struggle against the Nazis/fascists opponents – often ended up cooperating regardless of the national borders not just to coordinate the military action towards victory, but also to assure peace and progress for the continent and, in prospective, for all humankind. In every country we were witness to a flowering of movements, actions, episodes, constitutional projects, in which the vision of the United States of Europe was an essential element that enriched the Resistance of a new profound and lasting political and historical dimension and content. In that moment some movements supporting the European unity were born in the six countries of “Little Europe”, in Great Britain, in Switzerland, in Austria and among some politically exiled (Poland, Czechoslovakia, …).

Of course, this desire for Europe was expressed with different intensities depending on the cultures of the countries at war. Of course, the Europeanist projects of the Resistance fighters are indebted to the political and philosophical circles in which they were born before the war, and they are part of currents of thought that existed before the war. Of course, not all the political parties engaged in the struggle against Nazi Europe (e.g. the Communist parties) were mobilized by the European issue. It would be little in line with reality to assert that the peoples of Europe were all ready for European conversion. Far from it.

But the merit of that handful of europeanists and federalists, forerunners of the times, which is historically mentioned in these pages, was great. By interpreting the changes that the World War II generated, with the new context opened by the transition from the European system to ←14 | 15→the world system of states, they were able to identify ante litteram in the overcoming of the absolute national state the basis for the construction of the new united Europe and, with it, of a new peaceful and democratic international order.

Above Hatred and beyond Borders: The French Resistance’s gradual realization of the need to make Europe

Robert Belot

Introduction

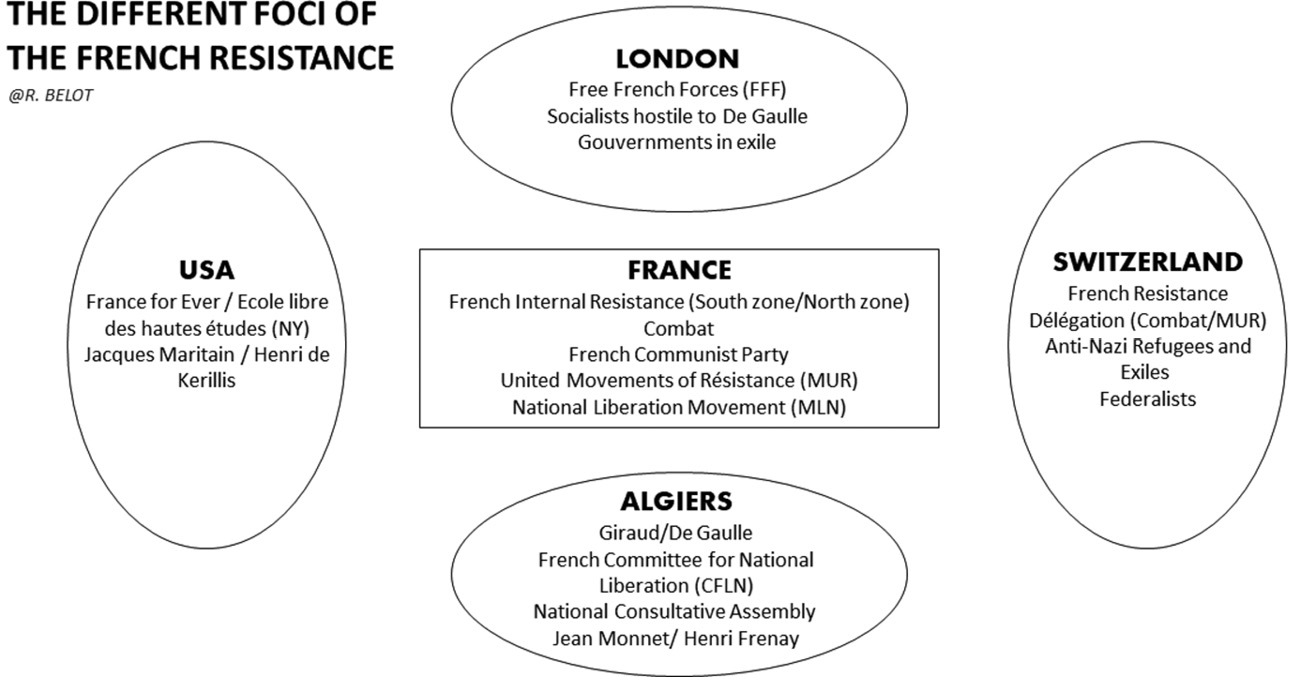

The Resistance in France sprung from a sudden outburst of patriotic awareness: “Outright refusal, an unquestionable imperative, an order straight from the heart to not submit”1. It also, gradually, became a source of propaganda in support of armed engagement. The Resistance was the product of an enlightened and courageous elite, intent on opposing both the Nazi occupier and the Vichy regime. It then, step by step, turned into a political project. This project aimed not only to restore democratic values in a new Republic, but also to consider the future role of France within a reshaped Europe that would have learned the lessons of those tragic years. Besides mainland France, where clandestine activity was the order of the day, the various destinations hosting the diaspora of the French opposed to the Nazi and Vichyist order (London, New York, Geneva, Algiers mainly) provided crucibles where new ideas emerged on the future world. Little by little links were forged with other European Resistances, thus strengthening hope and giving rise to converging ideas. The common struggle against Nazism and fascism encouraged this spearheading group to imagine the reconstruction of Europe on other bases. Fighters and intellectuals alike succeeded in raising “their spirit above misfortune and hatred” and tried to look “beyond war and beyond borders”. When the occupier was out of sight and out of mind, ←19 | 20→what kind of France could be imagined? What would its place and rank be in the new world? And how could this bruised and battered Europe recover its health? What was to be done with Germany and Italy? How could a position be found between the Americans and the Soviets?

The myth of a “resistant France”, which supposedly triumphed at Liberation and warded off the trauma of defeat and humiliation of occupation, has concealed the divisions existing among the “victors” and the fact that the process of Europeanizing minds was, in France, long, complex and a source of conflict. The desire for renewal, even revolution, which suffused the Resistance press in 1943 faded in the immediate post-war period. The European project would have to wait until 1948 before becoming a concrete prospect.

However, it should not be thought that there was a clear awareness of the importance of the European issue from the start. The Resistance was a polygenic, complex, dynamic phenomenon, with only minority support. Despite this, members and sympathizers of the Resistance did regard themselves as a “new elite”2.

The transformation of a moral and patriotic posture into a political project was, as I said, long and conflictive. Gaullism, born in London in June 1940, embodied the nationalist option to fight against the Germans, attracting, contrary to expectations, the Communists who joined the Resistance after the break-up of the German-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact. The Internal Resistance, which was formed independently from Gaullism and Communism, had a different genetics and a unique approach to the challenges of the post-war period. It was here, in Christian Democrat and socialist circles, that the idea of Europe and reconciliation with Germany took root. Between these three main poles of the fight against Nazi Germany, there was seldom any agreement on methods of combat or on ideas about how to rebuild France and Europe. The myth of a united Resistance would dissolve when political life resumed following Liberation. It was thanks to another war, the “Cold” War, that European aspirations would revive. The aim of this chapter is to analyse the reasons why the European cause presented such difficulties.

←20 | 21→Taking another look at the history of the origins of a European ambition is also one way of countering today’s anti-European theses (both from the right and the left) that present the European post-war project as a geopolitical tool of the United States, used to achieve a “liberal plot”, relayed by a handful of influencers (notably Jean Monnet) who were divorced from historical reality and devoid of all patriotism. These theses have one thing in common: they manipulate or misunderstand the history of the rebirth of the European idea, a rebirth that took shape in that “army of shadows” composed of men and women who, in the name of peace and freedom, decided to risk their own freedom or their very lives to fight against the Nazi order and the looming reality of a Europe subject to the worst of all worlds. To ignore this origin would be to deny the legitimacy of the European struggle, born during the dark night of Nazi domination, and to denigrate the risk taken by those who wished to build a Europe of peace and democracy.

1. A patriotic reaction to German occupation

The original Resistance on French soil, what is known as “proto-Resistance”, began as a low rumble. It was an unorganized and marginal phenomenon, resulting mainly from individual or small group reactions. It expressed a rejection of the German occupier’s system, in line with a long French anti-German tradition. This patriotic outburst, more internalized than substantiated, was largely apolitical and did not present itself as an opponent of the Vichy regime with Marshal Pétain at the helm, or, at least, not at the beginning of the occupation.

1.1. Dangerous illusions of apolitical patriotism

The idea that the French Resistance, in its multiple forms and immediately after the defeat of France (June 1940), had a clear awareness of what the stakes involved in the war were and even more so what the aftermath of the war would bring must be totally discarded. First, the shock caused by this swift and brutal defeat, the drama of the exodus and trauma of a humiliating occupation had to be overcome. The American historian William L. Langer, in 1948, summed up the context very well: Pétain was “deeply respected” because the French believed in his will to “ultimately hoodwink the Germans and save France from ←21 | 22→complete annihilation”; the Republic “rightly or wrongly was discredited”; Britain’s chances “seemed slim”; de Gaulle “almost completely unknown”3.

Having said that, it should also be borne in mind that the French Resistance4 was a unique and unprecedented phenomenon: polygenic and dynamic, it sprang up in very different places (the French interior, London, the United States, Algiers, Switzerland) in various shapes and sizes. It stemmed first from a survival instinct and an intention to fight against the oppressor and would slowly become a revolt against the Vichy regime and Nazi ideology. If the Anglo-Saxons were waging war on Nazism but not on the Germans, Europeans, for whom Hitler was only the personification of the Germanic threat, were primarily fighting against Germany5.

The “Resistance”, an all-encompassing expression that brought together extremely diverse situations and positions, was anything but a united movement. It represented a composite, shapeless, arbitrary reality, ←22 | 23→the social resonance of which was certainly very weak during the first two years of the occupation.

Three elements dominated the first reactions of those who refused to submit to German occupation or to the collaborating Vichy regime, led by Marshal Pétain: patriotism, which could be described as instinctive; hatred of the Germans who had occupied the country; and rejection of the political world, which was responsible for having allowed the disaster to happen in the first place. This can be observed in underground newspapers, General de Gaulle’s first speeches, correspondence, leaflets, statements by exiles, etc., but with one notable exception, the Communists, whose statements were constrained by the German-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact until June 1941.

The internal French proto-Resistance (as opposed to the “external” Resistance outside the mainland) claimed to be patriotic, apolitical and limited to the “native soil”. One French journalist based in London decided not to respond to General de Gaulle’s appeal and to return to France because he wanted to “share the sufferings of his compatriots” and not “escape the hardships of his native soil”6. The underground newspaper Défense de la France, for example, condemned those who, wishing to resist, “turn to communism or to the foreigner”. Its issue of August15, 1941, perfectly expresses this hexagonal and obsidional tropism. The title of Philippe Viannay’s editorial (Indomitus) sounds very similar to the motto of the far right Action Française: “Une seule France”. There is talk of “hating the enemy” and “loving France”. The article entitled Neither Germans, Russians, or English ends on a note of France-centered rhetoric:

Written by French people, for French people, with mainly French concerns, it is the only French voice that rises above the current lies and flattery. A stranger to any ideology, independent and free, it alone has the right to speak on behalf of France. It meets the wishes of all French people. It says out loud what everyone is thinking under their breath: that France will not let itself be strangled or seduced7.

Details

- Pages

- 562

- Publication Year

- 2022

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9782875744531

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9782875744548

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9782875744524

- DOI

- 10.3726/b19126

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2022 (January)

- Published

- Bruxelles, Berlin, Bern, New York, Oxford, Warszawa, Wien, 2022. 562 pp., 2 fig. b/w.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG