Locating the Self, Welcoming the Other

In British and Irish Art, 1990-2020

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

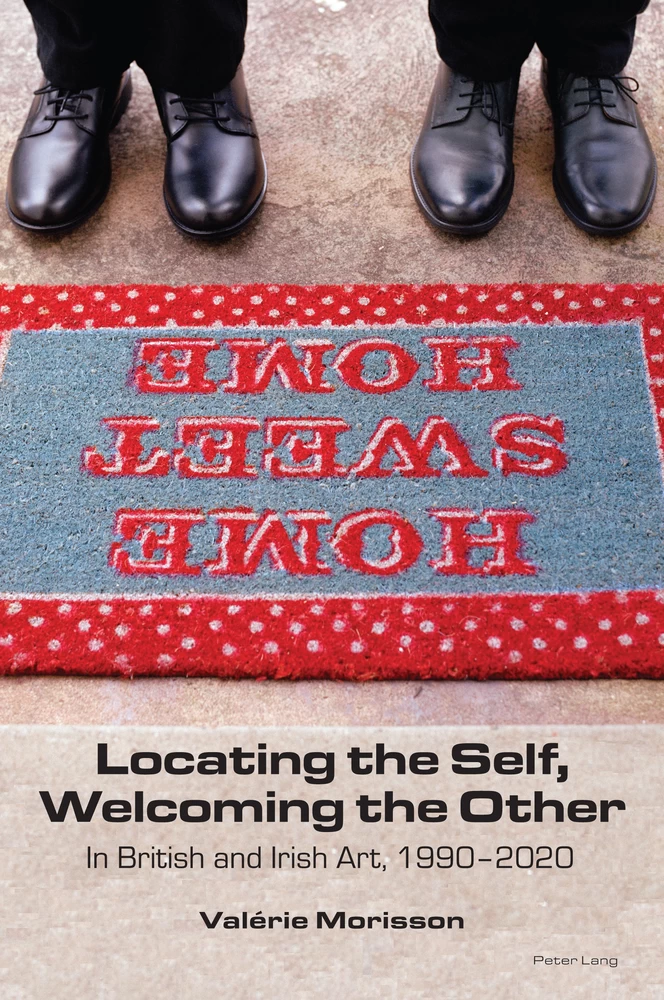

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Intimacy from the inside out

- Chapter 2 Domesticity gone awry: Parodying gender

- Chapter 3 Transitional objects: Collecting, recollecting, reconnecting

- Chapter 4 Revisiting rurality

- Chapter 5 Class-based perspectives: Occupying social and discursive spaces

- Chapter 6 Stranded souls

- Chapter 7 Toward utopia: Envisioning the future, restoring the commons

- Conclusion Dialogical positionality

- Bibliography

- Index

Illustrations

Figure 1. Shizuka Yokomizo, Stranger no. 9, 1999. Colour photograph. Courtesy of the artist.

Figure 9. Leslie Hilling, On Longing (detail), The Lightening. Mixed media. Courtesy of the artist.

Figure 10. Laura Blight, Dust Cave, installation view, 2018. Courtesy of the artist.←ix | x→

Figure 20. Kate Genever, You Complete Me, 2018. Scratched digital A3 print installed and now accessioned into the Museum of Contemporary Farming. University of Reading. Photograph credit and courtesy of the artist.←x | xi→

Figure 23. Oliver East, Mahers Gardens, 3rd visit, mixed media. Photograph courtesy of the artist.

Figure 25. Tom Hunter, from the series The Ghetto, 1993. Colour photograph. Courtesy of the artist.

Figure 30. Ailbhe Ní Bhriain, still from Great Good Places, Four screen video installation, 2011. Images courtesy the artist and domobaal, London. Original in colour.←xi | xii→

Figure 33. Isabelle Graeff, from the Exit series. Colour photograph. Courtesy of the artist.

Acknowledgements

This book would not have been written without the generous support of Catherine Bernard, professor at the Université de Paris Diderot, who encouraged me in this research project and its preparatory phases and followed the evolution of the various drafts for this book. Her renowned critical writings and her rigorous methodology have long been a model and a source of inspiration for me. My thanks also go to Isabelle Gadoin, Eamon Maher, Laurent Gauthier and Cécile Roudeau who helped me secure a CNRS research grant. I would also like to acknowledge the financial support of Textes Images, Langages (Université de Bourgogne Franche Comté) and the Laboratoire de Recherche sur les Cultures Anglophones (Université de Paris) and to thank my editor and the publishing team for their work.

My greatest thanks go to the artists who have generously shared information or material about their works, devoted time to online interviews even during the various lockdowns imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, proofread quotes or excerpts and provided images without requiring recompense that, unfortunately, could not be granted for reasons I regret. I would like to voice their fair demand for payment when images of their works are reproduced, even in academic contexts. The health crisis has made the situation of visual artists even more precarious and exhibition opportunities scarce. It requires from us – art writers and readers – even more respect, recognition and unflinching support.

To the artists. To those who devote their energy to the beauty and force of imagination even when it means going against the current. To all the young people and older adults who do not cease to chase their dreams despite a lack of encouragement or direct reward. When I was a teenager, my father would often deride my ambition to become an art writer. I dedicate this book to him to excuse his incapacity to understand who I was and who I am.

Introduction

Since the early 1990s and “the loss of a collective political horizon,”1 the multiple crises Western societies have faced – whether economic meltdown, climate change, the legacy of colonialism, unexpected migratory flows, or epidemics – have spurred artists, art critics and curators to position art as a means to imagine alternative ways of approaching these issues to foster inclusive, remedial and emancipatory practices. Our phenomenological and affective relation with space, belongingness and hospitality must be reconsidered in the face of these urgent problems. How can one define, think and imagine one’s relation to place in the context of recent cultural, social and political upheavals? What can artists contribute to contemporary debates on spatialized or localized identities that are too often pitted against global cultural forms and networks? How can art articulate individual and collective imaginings of space and map out new terrains of encounters between the self and the other? These are the questions I intend to ponder in this volume. I argue that artists have things to say, ideas to implement, projects to carry out so as to chart alternative conceptions of belongingness and citizenship.

If, as an art historian, one pays attention not only to art objects but also to art projects, processes and apparatuses, the capacity of artistic intervention to remap belongingness as profoundly relational becomes evident. Studying both artistic praxis and experience as situational, embodied and intersubjective allows us to acknowledge the capacity artists have to make us think anew and embrace being decentred. I have selected works addressing spatialized identities and deploying various forms of relational praxis to map out a three-dimensional cartography of encounters, which considers not merely artistic output but also the creation process and its reception.←1 | 2→

The corpus constituting this volume does not spring from the desire to explore the iconography of the home or to hierarchize practices according to their aesthetic merit, but from a preoccupation with praxis as an operative distribution of the sensible (partage du sensible), hence a constant attention to creative processes, to the way artists envision their relation to their environment and conceive meaningful apparatuses, which articulate phenomenology, ethics and politics. While works, installations and collaborative art are extensively discussed because they require a sustained immersion of the artist in a given place/situation and often allow for an interactive viewing experience, other forms are equally explored. Analyzing how art lodges relational ethics within aesthetics and charts the contours of inclusive belongingness has led me back to Jacques Rancière’s key notion of the distribution of the sensible, which relates art to the experience of the political and puts to the fore the intersection of the individual and the collective, of what divides and what connects.2

One of the assumptions behind this volume is that art does not illustrate political situations: its political dimension lies in praxis. Artistic creation is part and parcel of what Rancière calls “l’agir humain” [human activities].3 It is a matter of doing with: with reality, with material and format, with exhibition spaces or digital platforms. It does not produce consensus or homogeneity but fosters intersubjectivity:

A “common” world is never simply an ethos, a shared abode, that results from the sedimentation of a certain number of intertwined acts. It is always a polemical distribution of modes of being and “occupations” in a space of possibilities. It is from this perspective that it is possible to raise the question of the relationship between the “ordinariness” of work and artistic “exceptionality”.4

It is my hope to demonstrate that, as Rancière claims, artists combine the ordinariness of labour and the exceptionality of art. By foregrounding the situationality and relationality induced by artistic praxis, I intend to ←2 | 3→suggest that, in times when political discourse on identity and citizenship brandishes the spectres of regressive forms of nationalism, the distribution of the sensible activated by artistic praxis shores up the dialectical essence of belongingness, which Derrida’s portmanteau word, hostipitalité, encapsulates.5 This intersection of situationality and relationality is what I argue is central to a critical understanding of praxis, namely positionality.

The shifting grounds of place-bound identity

To some extent, this book finds its origin in a few lines written by Lucy Lippard in her often-quoted book, The Lure of the Local:

Most often place applies to our own “local” – entwined with personal memory, known or unknown histories, marks made in the land that provoke and evoke. Place is latitudinal and longitudinal within a person’s life. It is temporal and spatial, personal and political. A layered location replete with human histories and memories, place has width as well as depth. It is about connections, what surrounds it, what formed it, what happened there, what will happen there.6

Lippard convincingly states that “the search for homeplace is the mythical search for the axis mundi, for a centre, for some place to stand,”7 but she equally holds that our attitude to space needs to be understood in relation to geopolitical changes and identity politics. This introduction purports to articulate an invariant or structural understanding of our connection to space and a more time-dependent or contextual approach of spatialized identities. It equally puts stress on relationality, as this volume ←3 | 4→sketches a cartography of encounters through an in-depth review of contemporary British and Irish artworks dealing with domestic space.

Details

- Pages

- XIV, 388

- Publication Year

- 2022

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781800793941

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781800793958

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781800793965

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781800793934

- DOI

- 10.3726/b18222

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2022 (April)

- Keywords

- Representation of domestic space in art Belongingness vs. nomadic identities The crisis of hospitality Locating the Self Valérie Morisson

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, New York, Wien, 2022. XIV, 388 pp., 1 fig. col., 36 fig. b/w.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG