Alan Lomax, the South, and the American Folk Music Revival, 1933-1969

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Acknowledgements

- Contents

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Primary Sources

- Outline

- State of Research

- 1 American Folklore: Applied versus Pure Research

- 1.1 The Dual Meaning of Folklore

- 1.1.1 Advocating “the Folk”

- 1.1.2 Knowledge and Interpretation

- 1.1.3 Approaching the Irreconcilable

- 1.1.4 “Living Lore” as Contemporary History

- 1.2 The Folklore Approach of Alan Lomax

- 1.2.1 Making Folk Music Available

- 1.1.2 An Appeal for Cultural Equity

- 1.2.3 The Folklife Preservation Act

- 2 The Expert from Below

- 2.1 Lomax and the Publishing Media

- 2.1.1 “Music in Your Own Backyard”: Democratizing Knowledge in Folklore

- 2.1.2 Rural America: The Nation’s Democratic Backbone

- 2.1.3 Flirting with Cosmopolis: Lomax and Highbrow Culture

- 2.2 Between Advocating and Exploiting

- 2.2.1 Beyond Entertainment: Lead Belly and Henry Truvillion

- 2.2.2 Creating Intimacy: Lomax as the Friend of “the Folk”

- 2.2.3 A Machine for the Voiceless

- 3 Radio and Film

- 3.1 Radio as an Educational Force

- 3.2 The Rural South and the War Effort: Lomax at the Office of War Information

- 3.2.1 Folk Music of America and Back Where I Come From

- 3.2.1.1 Work and Prison Songs of the South

- 3.2.1.2 The Rural Messenger

- 3.3 Educational Film

- 3.3.1 The Integrated South versus the Benighted South

- 3.3.1.1 To Hear Your Banjo Play

- 3.3.1.2 Rainbow Quest

- 3.3.1.3 Ballads, Blues and Bluegrass

- 4 Gender, Race and the Folklorist

- 4.1 Gender- and African American Studies in Folklore Scholarship

- 4.1.1 The Accusation of Cultural Appropriation

- 4.1.2 Gender and Race Bias in History and Folklore Studies

- 4.2 Sidney Robertson

- 4.2.1 A Minor Voice

- 4.2.2 A Clash of Views

- 4.3 Zora Neale Hurston

- 4.3.1 Uniqueness out of Necessity

- 4.3.2 Eatonville Chronicler

- 5 “A Mississippi of Song”: Lomax and the Construction of Delta Blues

- 5.1 The Cradle of the Blues?: The Myth of the Delta

- 5.1.1 The Picture and the Mirror: Lomax and the Search for History

- 5.1.2 Urban North or Rural South: The Blues of Big Bill Broonzy

- 5.1.3 “Blues at Midnight”: Becoming a People’s Artist

- 5.1.3 Meeting Expectations: Broonzy as the Chronicler of the Blues

- 5.1.4 Blues in the Mississippi Night

- 5.1.5 Fiction or History: Lomax and “I Got the Blues”

- 5.1.6 “Three Delta Men”: The Blues in the Mississippi Night LPs

- 5.1.7 Lomax and the Use of Oral History

- 5.1.8 The Blues in the Mississippi Night Legacy

- 5.2 The Fisk / Library of Congress Coahoma County Study, 1941–1942

- 5.2.1 Natchez or Coahoma: Locating the Study

- 5.2.2 The Rediscovered Manuscripts: Lomax and the Fisk Scholars

- 5.2.3 Folk Culture and Popular Culture in Coahoma County

- 5.4.2 Work Song, Levee Song and the Holler

- 5.2.5 Native American Influence on the Blues

- 5.2.6 “Having the Blues”: A Very Short Survey

- 5.3 The Individual versus the Community: Lomax and Mississippi Bluesmen

- 5.3.1 Poor Muleskinner or Aspiring Artists: Muddy Waters

- 5.3.2 Emplotting the Narrative: Lomax and the “Royal Lineage” of Blues

- 5.3.3 “Possessed by the Song”: Lomax and Son House

- 5.3.4 The Modern Style: David “Honeyboy” Edwards

- 5.4 “They Lost Some of Their Melancholy”: Lomax and New Orleans Blues

- 5.4.1 Jelly Roll Morton and the Contamination of the Blues

- 5.4.2 Rural and Urban Blues in the Early Recording Industry

- 5.5 Lomax and the Female Blues

- 5.5.1 Storyville and the Limitations of Blueswomen

- 5.5.2 “They Could Bring it to Church”: Lomax and the Struggles of Blueswomen

- 5.6 Lomax and the Mississippi State Penitentiary

- 5.6.1 Negro Prison Songs from the Mississippi State Penitentiary (1958)

- 6 Lomax and the 1960s “Folk Boom”

- 6.1 Reflecting Privilege: The Search for Outsiders

- 6.2 The Driven Generation: The Lucky Few

- 6.2.1 A Story of Black and White

- 6.3 The Newport Folk Festival, 1963 to 1965

- 6.3.1 Lomax as Newport Board Member

- 6.3.2 The Folk Rediscoveries

- 6.3.3 Devil Got My Woman

- 6.3.4 Mediators of the “Folk Boom” – Rinzler, Shelton, Silber and Lomax

- 6.4 Rediscoveries of Appalachia

- Conclusion

- Primary Sources List of Figures

- Audio Recordings

- Series Index

Introduction

At the inauguration of President Joseph Biden on January 20, 2021, Woody Guthrie’s song “This Land is Your Land” was performed – a tune with a 70-year-old history especially among leftists and liberals. Since its release in 1952, the song has been played frequently as a sort of alternative national anthem. It is an obvious choice because of its alleged inclusive message of celebrating diversity. However, in recent years voices were raised questioning the song’s inclusiveness. This was also the case after the Biden inauguration where singer Jennifer Lopez performed the song live for millions of Americans. The song caused a heated debate revolving around the question of who is actually the addressee of Guthrie’s phrase “your land.” Although Guthrie may well have understood the song as a democratic message, it can also evoke a nationalist idea of Manifest Destiny. That Lopez herself has Puerto-Rican roots could not hide the fact that some minorities, especially Native Americans, may not have felt addressed by the song. The accusations were along the lines that although the song is considered a patriotic anthem, it represents a colonial message for others. As Smithsonian Folkways artist and activist Mali Obomsawin sums up the critique: “‘This Land is your Land’ is … indicative of American leftists’ role in Native invisibility.”1 For some Americans, it seems, Guthrie’s song is emblematic of the blind spots that the Left still has in its self-image calling for diversity and inclusion.

Guthrie’s song was born in the haze of the folk music revival, in which ideas of equality and diversity were the resonant space.2 One of the actors behind the revival was the song collector and folk promoter Alan Lomax, who was the first to record Guthrie in 1940 for the Library of Congress and became one of Guthrie’s main supporters and collaborators. Lomax coined the term Cultural Equity. It stands for the requirement that all cultural expressions should be promoted equally. But did Lomax really act according to his own maxim? Part of my work examines whether a similar sensibility than that found with Guthrie can be ←17 | 18→applied to Lomax. Like Guthrie’s song, Lomax’s work is based on the advocacy of some but at the exclusion of others. The irony is that both Lomax and Guthrie sought to make some of the most disadvantaged groups of America visible and audible through folklore, but both had a tendency to ignore other groups, regions, classes, and races. As a scholar of North American Studies, I believe that the relevance of folklore research in American society became clear at the Biden inauguration. The preservation and archiving of folk music take on a special role in America, precisely because questions of identity and belonging are always present. And because America is still a relatively new country, it has a constant obsession with preserving things from the past. Woody Guthrie is part of that heritage and became a source of pride for many Americans.3 The Biden inauguration was particularly keen to make the ceremony a celebration of inclusion. In doing so, they used a piece of “folk culture” – Guthrie’s song – to support this message. However, not only Guthrie’s song was staged, I would argue, but his very aura, what Guthrie represents. More than anyone else, I believe, he stood for the “voice of the common man,” an attribute which makes him particularly predestined to reach “ordinary” Americans. And this phenomenon was part of the reason why his spirit was not only present at the Biden inauguration but also at the inauguration of President Barack Obama, in 2009, where the same song was performed by Bruce Springsteen and Pete Seeger.

It was the work of Alan Lomax that contributed in no small measure to this image of the “voice of the common man.” He drove the cultural work behind Guthrie’s image like no other. And in his zeal to promote the music of the rural downtrodden, Lomax didn’t realize how much he was committing himself to a particular region, ignoring most of the country, regionally and culturally. Of course, it is a lot to ask of a song collector to cover a nation’s entire cultural variety. But this does not change the problem that especially in America, the exclusion of regions and populations in the American song canon often brings to light the nation’s identity problems. Lomax’s work has often been held up as a colorful representation of the diversity of America’s regional cultures. This was also the case in an article published in 2014 by historian Ronald D. Cohen, titled “Bill Malone, Alan Lomax, and the Origins of Country Music.” Cohen is a luminary in the field of American vernacular culture and his work – for which I have ←18 | 19→great respect – also has a wide appeal. However, I found the position Cohen takes in the article regarding Lomax’s legacy even more surprising. Namely that Lomax’s work was a leading example of an approach that included the nation’s diversity of song culture. In his article, Cohen compares Lomax’s work to another well-known historian, Bill Malone. Cohen makes the claim that country music in America – although originally played throughout the entire nation in the form of local, vernacular music – was constructed as a specifically Southern genre by both historians and the early recording industry. He focuses on the work of Bill Malone, whom he calls the “dean of country music historians,” and who, in 1968, published his landmark book Country Music U.S.A., in Cohen’s view, “the touchstone for all future studies.”4 Cohen argues that instead of focusing on the South, “country music [studies] should take a national approach,” and he points to the work of folklorist Alan Lomax who, in Cohen’s view, represents such an approach. According to Cohen, at the time Malone’s book was published, Lomax’s preferred term “folk music” covered the same music than Malone did – non-commercial and commercial American vernacular music – but in a more inclusive manner. As stated by Cohen, Lomax pursued a more varied, complex understanding of the music and the people who crafted it. Lomax’s approach, he announces, included not only a rich variety of ethnic music but also the collection of music in various areas outside the American South: “Alan Lomax would have agreed that Southern music should not be given priority by folklore collectors,”5 he concludes. Furthermore, Cohen takes the position that Malone’s study became so influential in part because Lomax was “rarely mentioned in studies of country music” and he asks whether this was also because of “the fault of Lomax’s wide-reaching tastes and interests.”6

In this dissertation I want to make two main points in relation to Cohen’s argument. (1) Even though I think Cohen is right in his assessment that Malone’s “country music” was included in Lomax’s concept of “folk music,” I do not agree with Cohen’s claim that Lomax pursued a “national approach” in his studies or in his promotion of vernacular music. Instead, I argue that Lomax – although pursuing a more ethnic approach – studied, preserved, and promoted American vernacular music that was mainly of Southern origin or had migratory ties to the ←19 | 20→South.7 And that this emphasis on the South was a result of Lomax’s advocacy of the cultures of perceived marginalized Americans whom he located primarily in the South. (2) The claim that Lomax would be “rarely mentioned in studies of country music” does not mean that he did not influence cultural actors of all kinds – even those from the field of “country music.” Lomax, I argue, carved out a niche for himself as an “expert from below,” an intermediary position which allowed him to take a special role in both the scholarly world and the world of popular culture. In his myriad professions as journalist, scholar, archivist, talent scout, song collector, radio and television host, writer, and producer, Lomax created the kind of groundwork that significantly shaped mainstream conceptions of what constitutes American vernacular music.

To define my two theses in more detail, let us take a closer look at Cohen’s arguments. He first defends his claim by citing a letter Lomax wrote to his boss, Librarian of Congress Harold Spivacke, in 1938, about his recent Midwestern song expedition and about his future recording plans.8 Cohen quotes Lomax:

The material gathered on the Archive’s exploratory trip to Indiana and Ohio has afforded us a partial idea of what has happened to Anglo-American folk music in the Middle West. Both of these states, however, have been influenced more by currents of cultural migration from the south and less by the intrusion of foreign language groups and by the flow of migration from New England than other Lake States. I feel it is important, therefore, before venturing further west that the Archive turn its attention to the Lake States—Michigan, Wisconsin and Minnesota—a study of which will give us a picture of an area culturally different from the Middle and Far West and yet important in the growth of these areas. In sounding folklore resources of this region, the Archive will be able to record what remains of the once vigorous lumber-jack culture, to explore the musical potentialities of the many foreign language groups of that area (Swedish, Norwegian, Finnish, Gaelic, French-Canadian, etc.) and to observe what have been the results of the mixing of these cultures with the Anglo-American matrix.9

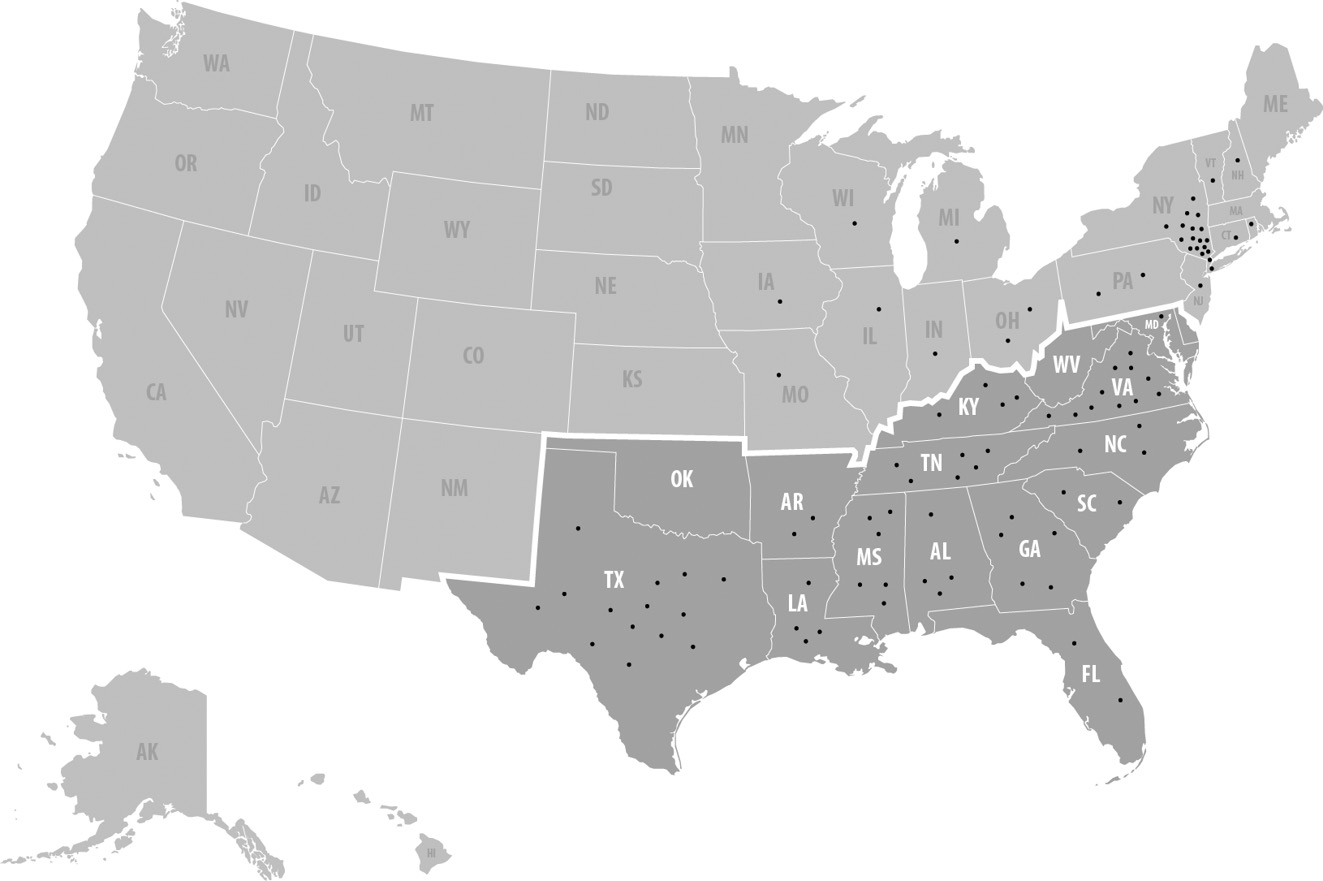

Even though it is true that Lomax underwent a recording trip in the Great Lake region in 1938, the expedition must be seen as an exception rather than a rule for Lomax’s other field trips. To visualize Lomax’s recording activities in the United States between 1933 and 1969, I created a simple map which shows where ←20 | 21→Lomax recorded during these years (Fig. 1).10 The individual dots on the map each represent the individual recording undertakings by Alan Lomax as listed in the “Chronological Guide to Lomax Field Trips and Recordings” by the Library of Congress.11 Within each state the dots are arranged randomly and say nothing about in which county, city or small town Lomax made the recordings. This is because the points represent single expeditions. And Lomax mostly visited several locations at once.12

Fig. 1

←21 | 22→Although the depicted map is somewhat “distorted” in the sense that it neither says where exactly within a certain state Lomax recorded nor how extensive the respective expeditions were,13 it still gives a good first impression as to where (in which states) Lomax made his recordings. Already at first glance we can see that he recorded significantly more inside than outside the South.14 If we would add the locations Lomax recorded from 1970 to his last US-based recording in 1985, the picture would be even clearer as Lomax still primarily focused on the South.15 However, I chose to only visualize the time between 1933 and 1969 for ←22 | 23→mainly two reasons: First, the late 1960s mark the end of the folk music revival16 in the United States and thus the time where the major preconceptions about vernacular music have been constructed. And it roughly marks the boundary from when Bill Malone released his 1968 study Country Music U.S.A.

Of course, not only recording trips say something about how much emphasis on a particular region a music historian places in his research. But since Cohen builds his own argument with Lomax’s allegedly variant recording trips, it should be made clear here that Lomax already leaves clear traces in his professional travels. Furthermore, as Lomax’s comment about “Indiana and Ohio” and their being “influenced by the cultural migration of the South” suggests, he was often concerned with exploring Southern music even in places outside of the South. For if one takes a closer look at his research in Indiana and Ohio, one finds that Lomax regarded them as “heterotopias” of the South. The two states were the main destinations of the so-called Hillbilly Highway, the route which brought many job-seeking Kentuckians to industrial places upnorth during the Appalachian migration. Lomax’s field trips, I believe, reflect that pattern.17 The striking frequency of recordings in New York is partly because Lomax lived in the city for most of his life and was therefore often there. On the other hand, the city was not only the media and music capital of America, and therefore a popular destination for musicians, but it was the very center of the folk music revival. If we look up the performers Lomax recorded in New York from 1933 to 1969, we find that of 26 known subjects18 14 were born in the American South, six persons were born outside the South, and five were born abroad (one person ←23 | 24→is unknown).19 Of the 27 recording sessions conducted by Lomax within the Library of Congress, 13 were from southern-born performers, 10 from non-Southerners and 2 from performers born abroad (2 remain unknown).20 Even though this result looks more balanced, the majority of performers were born in the South. If one also considers that the Southern states consist of only 16 states, while the non-Southern states have a total of 33, things look even clearer. Thus, in both locations, New York and Washington D.C., most Lomax recordings originate from Southern-born performers. Something similar can be said about the recordings in the state of Connecticut. The recordings made there – at John Lomax’s home in Wilton – were of the musicians Lead Belly and Aunt Molly Jackson, both natives of the South.21

Details

- Pages

- 450

- Publication Year

- 2022

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783631875889

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783631875896

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783631867723

- DOI

- 10.3726/b19594

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2022 (April)

- Keywords

- Alan Lomax American folk song marginalized Americans

- Published

- Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Warszawa, Wien, 2022. 450 pp., 11 fig. col., 17 fig. b/w.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG