Milton in Strasbourg

A Collection of Essays based on papers delivered to the IMS12, 17-21 June 2019

Summary

Opening with a tribute to all Milton symposia organized since 1981, the book falls into eight parts, covering all aspects of Milton studies. "Milton and Materiality" starts with an essay by James G. Turner on personal bodily reference in Milton. In "Milton’s Style and Language", the polemicist’s use of satire is scrutinized and his relation to enthusiasm is examined, while a new light is shed on his sonnets. In "Milton’s Prose", in a rare essay on Observations upon the Articles of Peace (1649), David H. Sacks compares Milton’s view of Ireland with what he thought of Russia, delving into the notions of "civilization" and "tyranny". Then the reader will find six essays on Paradise Lost, including one by Hiroko Sano, followed by three essays on his minor poems by promising scholars. The debate on the authorship of De Doctrina Christiana is reopened, with many stylometric tables and charts. A new track leads us to Silesia.

In "Reception Studies", two Brazilian contributors study Milton through the lens of French philosophers, and the next essay by Christophe Tournu focuses on the first French verse translation of Paradise Lost. The concluding part, "Milton and his Audience", considers Milton’s relationship to his readers, music in Haydn’s Creation, while Beverley Sherry analyses portraits of Milton and his works in stained glass.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the editors

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword by Michel Deneken, President of the University of Strasbourg

- Contents

- Introduction

- Part I Milton and Materiality

- Milton’s Skin (James Grantham Turner)

- “So all was cleared”: Corrupted Fancy and Purgative Tears in Paradise Lost (Sarah S. Keleher (née Rice))

- Milton’s Deafened Moment (Miles Drawdy)

- Part II Milton’s Language and Style

- Scripture, Scorn, and Milton’s Dynamics of Derision (David Currell)

- Milton and the Political Sonnet’s Deep State (Lana Cable)

- Milton, Sublime Style, and the Problem of Enthusiasm (Thomas M. Vozar)

- Part III Milton’s Prose

- “Knots and Twirls”: Conflictual Metaphors in Of Reformation (Daniele Borgogni)

- “Better To Marry than To Burn”: Milton’s Deliberate Translation of Paul (Matt Dolloff)

- John Milton’s View of the Present State of Ireland (David Harris Sacks)

- Part IV Paradise Lost

- “Short” in Paradise Lost (Neil Forsyth)

- Doré’s Illustrations to Paradise Lost and to The Holy Bible (Hiroko Sano)

- “Tyranny must be” (PL, XII, 195): Milton’s Politics of Heaven in Paradise Lost (Victoria M. Griffon )

- Satanic L/Imitations. “Who, being in the form of God, thought it not robbery to be equal with God (Phil. 2:6)” (Ágnes Bató)

- “In a troubled sea of passion tossed”: Adam, Hamlet, and Skepticism in Paradise Lost and Hamlet (Bradley Fox)

- Whither Goes AI: Paradise Lost, Frankenstein, Ex Machina, and the Boundaries of Knowledge (Tianhu Hao)

- Part V Other Poems

- Milton as Phoebicola, a Follower of Phoebus: The Pauline Poet in His Latin Poetry (Chika Kaneko)

- Virgil’s Disappearing Wives in Milton’s Sonnet 23 (Ian Hynd)

- “My Heart Hath Been a Storehouse of Things”: The Passionless Son in Paradise Regained (William Yang)

- Part VI De Doctrina Christiana

- Another Candidate for the Primary Authorship of De Doctrina Christiana, the Anonymous Treatise Currently Attributed to Milton (Hugh Wilson and James Clawson)

- Part VII Reception Studies

- “J’ai cru servir la littérature, j’ai désiré de bien mériter de la patrie” – A Study of Fidelity in Translation as Viewed in the Case of Abbé Leroy’s Paradis perdu (1755) (Christophe Tournu)

- The Lists of Paradise Regained: An Economy of The Full and The Empty (Luiz Fernando Ferreira Sá)

- The Brazilian Milton: Innovation, Recreative Spirit and Absence in Machado de Assis and Guimarães Rosa (Miriam Piedade Mansur Andrade)

- Part VIII Milton and his Audience: The Miltonic Reader, Listener and Viewer

- Donne, Milton, and the Understanders (Warren Chernaik)

- “Now Chaos Ends and Order Fair Prevails”: A Rationalistic Interpretation of Milton’s Paradise Lost. The Oratorio The Creation by van Gottfried Swieten and Joseph Haydn (Beat Föllmi)

- Milton in Stained Glass (Beverley Sherry)

- About the Authors

- Index

Introduction

Sixteen years have elapsed since the Eighth International Milton Symposium was held in Grenoble, a little provincial city nestled in the valleys of the French Alps, and Miltonists rallied from 21 countries across the globe to talk about “Milton, Rights, and Liberties”, the main conference theme. In 2019, after London (2008), for the quatercentenary of Milton’s birth, Tokyo (2012), and Exeter (2015), Strasbourg was honoured to host the Twelfth edition of the Symposium. Once again, people from around the world, from Japan to Mexico, from Canada to New Zealand, from the US to Europe, flurried to a Milton spot. For five working days, in Strasbourg, at the Palais universitaire, the Great and Small Miltonists “In close recess and secret conclave sat / [two hundred] Demy-Gods on golden seats / Frequent and full.” The leader of the Miltonic crew was once again Neil Forsyth, an Englishman from Switzerland – as in 2005; he repeated the not so vain attempt of gathering a global crowd of swarming fans, and all paid tribute to “the general”.

The Strasbourg Connection

This time, the main conference theme was “Milton’s Politics of Religion”. The topic was chosen because of the particular position of Strasbourg. Indeed, Strasbourg is the capital of Alsace and, since Napoleonic times, has had a special status. Ten years after the French Revolution, when Napoleon came to power (1799), one of his main objectives was to achieve peace – including religious peace, to soothe one of the great wounds of the French Revolution, which had widened a gulf within the nation. As a matter of fact, with the end of the Ancien Régime society in 1789, the Catholic clergy no longer occupied the leading position in French society. With the passing of the Civil Constitution of the Clergy in 1790, the clergy was elected by the citizens and became civil servants, ←19 | 20→and had to take an oath of fidelity to the Constitution.1 Then there was a dechristianization movement during the Terror years, and after the Coup of 18 Brumaire,2 Bonaparte was eager to reconcile the Catholic Church.

The Concordat is an agreement signed on 15 July 1801 by the representatives of the First Consul, Joseph Bonaparte,3 and of the Pope, Cardinal Consalvi, and ratified in the following weeks by the First Consul Bonaparte and by Pope Pius VII (papal bull Ecclesia Christi, 15 August 1801).

The main lines of Concordat concern the freedom of worship of the Catholic religion within the French Republic and the appointment and remuneration of the clergy. According to the terms of the agreement, Catholicism was no longer the State religion, but remains the “religion of the majority of French people” (art. I).4 In exchange for the appointment of archbishops and bishops by the First Consul, bishops, parish priests and servants were to be remunerated by the Republic (art. XIV).5 The bishops, before taking office, shall take directly, in the presence of the first Consul, the oath of fidelity expressed in the following terms:

I swear and promise to God, on the holy Gospels, to keep obedience and fidelity to the Government established by the Constitution of the French Republic. I also promise not to have any intelligence, or to attend any council, or to maintain any league, either inside or outside, which is contrary to public tranquillity; and if, in my diocese or elsewhere, I discover that ←20 | 21→something is going on to the detriment of the State, I will let the Government know (art. VI).6

The same oath was to be taken by the clergy of the second order (art. VII).7

The Concordat was abolished by the law of 9th December 1905 concerning the separation of the Churches and the State,8 which is still debated today in the context of the surge of Islamic radicalism. The “principles” of the new law are encapsulated in the first two articles: 1. The Republic ensures freedom of conscience and guarantees the free exercise of religion provided there is no disturbance to public order. 2. The Republic does not recognize, pay, or subsidize any form of worship.

Yet, as Germany invaded Alsace-Lorraine in 1870 and its occupation lasted until 1914, the Concordat remained in force there and has not even been abolished ever since.

Had Milton been living in France in the beginning of the twentieth century, he, as the author of A Treatise of Civil Power in Ecclesiastical Cause (1659), would certainly have applauded the separation of the Church and State, and, as the author of The Likeliest Means to Remove Hirelings out of the Church (1659), he would also have approved of the plan of the French government to stop giving a maintenance allowance to clergymen.

If Milton obviously was not living in France in the beginning of the twentieth century, his name was mentioned and he was furthermore quoted in the debates at the National Assembly in the drafting of the ←21 | 22→law. A French MP, Mr. Eugène Réveillaud,9 a journalist, lawyer, historian, and politician, called upon Milton to support his view:

Mr. Eugène Réveillaud. I return to the Reformation to find in the pen of a great English poet, the author of Paradise Lost, who was at the same time a great theologian and a statesman, Cromwell’s much listened to adviser, this idea that we can call the idea of the new world, the great thesis of the freedom that must be granted to all opinions, to all cults. I want to bring back here this profound word of John Milton … (he is interrupted)Mr. Julien Goujon10 (Seine-Inférieure).He was blind.Mr Gabriel Deville.11That does not prevent him from speaking well.Mr. Eugène Réveillaud.… “Though, he said, all the winds of doctrines are unleashed onto the world, if the truth lies in the middle, we have nothing to fear. Let truth and falsehood take hold of each other; who has ever heard it said that truth was defeated, put to the test, when the meeting was fair on the field of freedom?”Here, formulated by this act of faith in freedom, in the power of truth against all its adversaries, is the fruitful principle of the new times, the normal idea which must henceforth regulate the relations of the State, the consciences and the Churches. It is this norm, this principle that we will consecrate in this legislature by voting this great law, the greatest that has been deliberated and voted on for a century, this law of the separation of the temporal and the spiritual, of the reciprocal independence of the State and the Church. (Very good! very good! to the left).12 [My translation]←22 | 23→

This is quite strange: Milton, though a republican, was often considered a liberal and therefore could not conceivably be recuperated by socialists to support their own views. It is yet precisely what they did in 1905.

Two figures further relate Milton to Strasbourg: Martin Bucer and Gustave Doré.

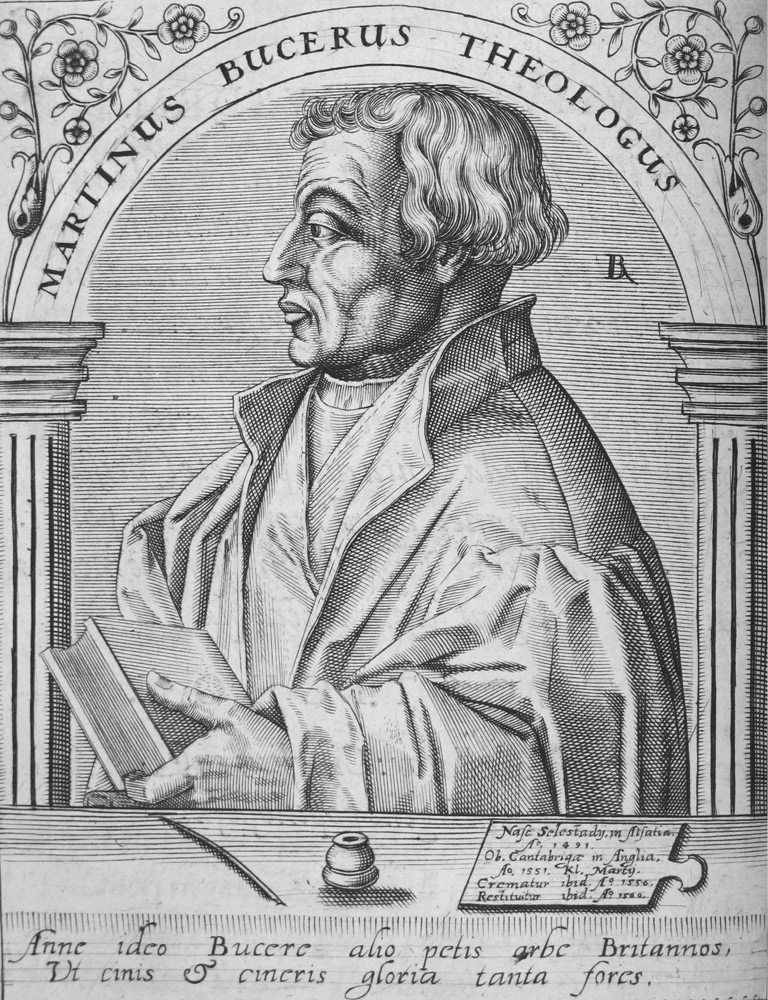

Martin Bucer

Martin Bucer was born in Sélestat, thirty-five miles south-south-west of the Alsatian capital, on 11 November 1491. Educated as a Dominican in Colmar, Bucer met Luther in Heidelberg in 1518 and converted to Protestantism, and he was called to preach the Reformation in Wissembourg. The German Protestant reformer was excommunicated by the bishop of Spire13 and fled to Strasbourg, where he was to stay between 1523 and 1549. Strasbourg was then a Free Imperial City (in German: Reichsstadt Straßburg), hence a former city-state under the direct jurisdiction of the Holy Roman Empire. It obtained its status by freeing itself from the political domination of its bishop at the end of the battle of Hausbergen in 1262, and was entitled to full privileges in 1358. Strasbourg was to retain its territorial independence until Louis XIV and his ←23 | 24→troops marched into the City (1681). As early as 1521, Martin Luther’s theses were known, published and preached in Alsace, notably in Strasbourg by the cathedral priest, Matthieu Zell. In 1524, the old world was turned upside down: after a short wave of iconoclasm, the first cults in the vulgar language were celebrated as well as the first marriages of clerics; henceforth the Magistrate, that is, the three city councils, plus the Ammester (alderman), appointed pastors. Wolfgang Capito, Bucer and Caspar Hedio settled in the city and took up preaching positions. Bucer set up Bible reading classes. That same year, the city council assigned the cathedral, which was built from 1015 to 1439 in Rayonnant Gothic architecture, to the Protestant faith. The last step was taken in 1529: the Latin mass was banned. Normative texts were published to provide a framework for society. Religious affairs were henceforth handled by the ecclesiastical court, under the authority of the Magistrate.

After Calvin was dismissed from his post in Geneva, Bucer managed to attract him to Strasbourg, where he was to stay for three years (1538–41). Calvin was to teach in the Haute École (high School), which was to become the University of Strasbourg in 1621.

Accused by some of being an enthusiast, that is, infected with Anabaptist notions, Bucer was expelled from Strasbourg by Charles V (1549) and exiled to England at the invitation of Archbishop Thomas Cranmer. There, he was presented to King Edward VI on 5 May 1549, and was appointed Regius Professor of Divinity at the University of Cambridge until his death in 1551. Queen Mary I had his remains exhumed and publicly burnt in 1557. De Regno Christi, his last book, was published posthumously in Basel in the same year14 and two French editions appeared in both Lausanne and Geneva in 1558.15 To support his own case, Milton translated the chapter on divorce, which he published as The Judgment of Martin Bucer concerning Divorce (1644). And, in the preface to the book, he mentions Strasbourg:

Yet did not Bucer in that volume [De Regno Christi] only declare what his constant opinion was herein [on divorce], but also in his comment upon ←24 | 25→Matthew, written at Strasburgh divers years before, he treats distinctly and copiously the same argument in three several places.16

Indeed, exactly thirty years before his De Regno Christi, Bucer had published Enarrationum in Evangelia Matthaei, Marci, & Lucae, Libri duo (Strasbourg: Johannes Herwagen, 1527), a book in which he commented upon Mt 5: 32 and 19: 9, two scriptural texts dealing with the interdiction of divorce, “saving for the cause of fornication,” and remarriage with a divorced woman.17 Three years later, the work, much augmented and including his commentary on John’s Gospel, was reissued as Enarrationes perpetuae, in sacra quatuor Evangelia (Strasbourg, Georg Ulricher, 1530).18

Milton was well informed about Bucer, his theory of divorce, and Strasbourg itself, as we can gather from the following passage:

Wherin his faithfulnes and powerful evidence prevail’d so farre with all the church of Strasburgh, that they publisht this doctrine of divorce, as an article of their confession, after they had taught so eight and twenty years, through all those times, when that Citie flourisht, and excell’d most, both in religion, learning, and goverment, under those first restorers of the Gospel there, Zelius, Hedio, Capito, Fagius, and those who incomparably then govern’d the Common-wealth, Ferrerus and Sturmius.19←25 | 26→

Here Milton alludes to Bucer’s Epitome, hoc est, brevis comprehensio doctrinae ac religionis Christianae, quae Argentorati20 annos iam ad XXVIII. publice sonuit (1548). Article XXI, entitled “Of Sacred Matrimony,” contemplates the possibility of getting a divorce:

But, if a divorce occurs, in accordance with or against the Word of the Lord, in this case, the Word of the Lord, the attitude of the first and true Apostolic Church, and also the Christian ordinances of the pious emperors will always be observed. (Mt 19 [: 3–9], Dt 24 [: 1–4]; I Cor 7 [: 10–15]; Ambrosia on the same; Co[de], 1. Consensu21)

Portrait of Martin Bucer by Johann Theodor de Bry, Copper engraving, circa 1612–13 (published 1627)

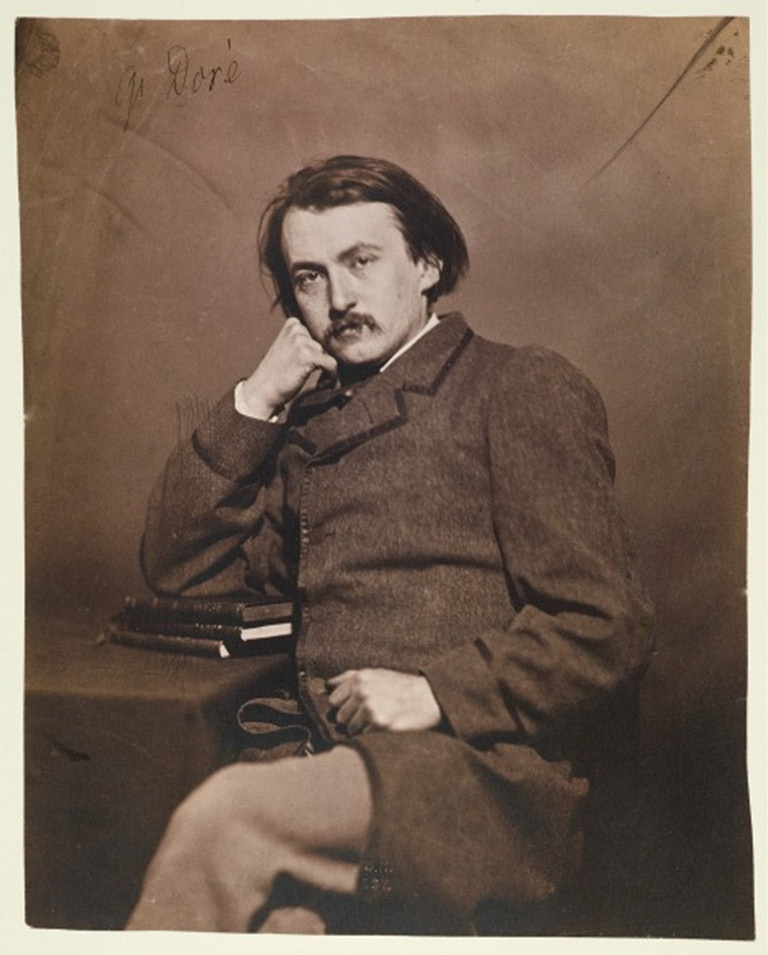

Gustave Doré

Another connection between Milton and Strasbourg was Gustave Doré, the famous illustrator of Paradise Lost. Doré was born in Strasbourg on 6 January 1832. At the age of fifteen, he was hired by Charles Philippon, the editor of the Journal pour rire, and within seven years he made no fewer than 1,379 drawings. The most famous album is The Works of Hercules, which, as the editor claimed, was realized by a self-taught fifteen-year-old child with no knowledge in the classics. In 1850 he exhibited his first paintings at the Salon,22 the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Paris – arguably the greatest annual or biennial art event in the Western world between 1748 and the end of the nineteenth century. Three years later, he published Petits Albums pour rire, twenty-four woodcut drawings for the Complete Works of Lord Byron. In 1854 he illustrated the Works of Rabelais, his first great success and twelve paintings entitled Paris As It Is. In a single year (1856), he produced more than 1,200 graphic illustrations. The Legend of the Wandering Jew by Pierre Dupont is the best-known illustrated work. Following his success, he was commissioned by the Ministère d’Etat to paint The Battle of Inkerman (5 November 1854), a decisive battle in the Crimean War which ended with an Anglo-French victory over the Russian Empire (1854–56). Then Doré turned to religious art: thus, in 1861, he illustrated Dante’s Inferno and began the ambitious project of illustrating masterpieces of world literature. Two years later, he published illustrations of Cervantes’ Don Quixote, Chateaubriand’s Atala, and Ernest L’Epine’s La Légende de Croque-Mitaine. In 1864, Napoleon III invited him to spend ten days in Compiègne, thereby establishing his reputation. In 1866, he illustrated Théophile Gautier’s Captain Fracasse, Paradise Lost,23 and the Holy Bible. Alfred Mame’s edition of La Sainte Bible selon la Vulgate (Tours, 1866) contained 312 drawings by Doré, in ←27 | 28→which “the illustrator gives full measure to the epic visions and scenes with the grandiloquent theatricality of the Old Testament, indulging in crowd effects, grandiose landscapes and dramatic scenes, served by powerful chiaroscuro effects.”24 In 1868 Fairless and Beeforth, art dealers, opened the “Doré Gallery” in London with his drawings and paintings, while the illustrator struck again with La Fontaine’s Fables and Tennyson’s Idylls of the King, a poem retelling the legend of King Arthur. In 1870 he enlisted as a National Guard during the Franco-Prussian War and painted The Marseillaise, from the song which a French army officer, Rouget de Lisle, had composed while in garrison in Strasbourg in 1792.25 Doré’s last major work was the illustration of Ariosto’s Roland Furieux (1879), for which he produced no fewer than 618 drawings. In 1880 he exhibited a sculpture called “La Madone” at the Salon.26 The monument for Alexandre Dumas, which was inaugurated in Paris on 4 November 1883, was his last work: Doré had worked six months on the sculpture of Dumas père (the elder), whom, according to Dumas fils (the younger) he resembled in so many ways27 – not least because of his profuseness – before he died of a heart attack on 23 January 1883.

Milton’s Paradise Lost: Illustrated by Gustave Dore (1866) was a large, elegant folio volume, bound in best polished morocco, with fifty full-page original engravings. This luxury edition, which sold at £10 (or £5 if bound in cloth) was followed by a popular edition five years later: Milton’s masterpiece, containing Doré’s illustrations, “the first which he especially executed for the British Public”28, as the publishers advertised, was to be issued in monthly parts, selling at two shillings each, and completed in sixteen parts. “The Doré Milton,” as they said, was to be made affordable for everyone to see the magnificent engravings.←28 | 29→

Portrait of Gustave Doré Photograph by Felix Nadar (circa 1860) (Courtesy of BnF)

Summaries

This volume falls into eight parts.

Part I

In Part I, “Milton and Materiality”, James Grantham Turner, in “Milton’s Skin”, wonders why a distinguished statesman and poet, in the midst of justifying the most drastic coup d’état in European history (the trial and execution of the King, the ensuing abolition of the monarchy and establishment of a Republic), would insist on telling us what great skin he has. Partly, of course, because his attacker (Pierre du Moulin) has resorted to ad hominem insults. But for Milton this is much more than a rhetorical tactic: he wants to claim that despite the ravages of age and blindness he embodies virtue, quite literally and corporeally. Milton invites the proper reader of this Latin Second Defence to experience the ←29 | 30→seductive presence of the author, to look into eyes that still look clear and touch that perfect complexion. By the same logic he must try to destroy his opponent in the flesh, de-facing him. As scholars and teachers, Miltonists need to get under that skin.

Then, two of his PhD students, Sarah Sands Rice and Miles Drawdy, bring their own contributions. In “‘So all was cleared’: Corrupted Fancy and Purgative Tears in Paradise Lost”, Rice argues that Early modern physiology conceived of imagination as a corporeal phenomenon, and a poisoned imagination could be quite a literal complaint. It is in that sense that Milton describes Satan “inspiring venom” into Eve’s ear to access “the organs of her fancy” and “taint / The animal spirits that from pure blood arise.” Satan prompts Eve to “distempered thoughts” by distempering her body. He renders her animal spirits – and perhaps even the blood from which they arise – impure. Eve’s dream and the symptoms of biological imbalance that she displays upon waking demonstrate that Satan’s venom has had its desired effect: an effect that is, at root, biological. The materiality that Milton grants to Satan’s poisoning of Eve’s imagination radically disrupts the narrative of bodily corruption appearing as a result of the Fall. Instead, Satan’s physical corruption of Eve’s imaginative faculties precedes and enables Eve’s moral corruption, compromising her agency in the Fall. The entry of sin into humanity becomes a matter of the introduction of an external, material evil into the human body, and impurity of spirit becomes inseparable from impurity of substance. Miles Drawdy is also concerned with the ear – hearing or rather non-hearing (deafness). Materialist philosophies of the seventeenth century – to the extent that they are empirical – are fundamentally invested in both the senses and language. For this reason, deafness presented a complicated challenge: the uncooperative ear was understood to be incompatible with the idea of a universe elegantly and exhaustively defined by the interaction of material substance. This begins to explain why Hobbes describes deaf persons as irrational (or, at the very least, as incapable of abstract thought). Milton, however, makes deafness a fundamental characteristic of postlapsarian experience. Especially throughout his earlier poems, Milton explicitly characterizes fallen man as deaf to the song of the celestial spheres and needing to learn to hear. Drawdy situates Milton’s materialism among that of his contemporaries by focusing on his description of the deaf experience. In doing this, he relates Milton’s philosophical project – and materialism more broadly – to contemporary experiments in deaf education.←30 | 31→

Details

- Pages

- 548

- Publication Year

- 2022

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9782875744258

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9782875744265

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9782875744241

- DOI

- 10.3726/b19772

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2021 (August)

- Keywords

- cutting-edge research papers from the XIIth international Milton Symposium Milton symposia Milton and Materiality

- Published

- Bruxelles, Berlin, Bern, New York, Oxford, Warszawa, Wien, 2022. 548 pp., 24 fig. col., 10 fig. b/w, 8 tables.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG