Current Issues and Empirical Studies in Public Finance

Summary

brings together studies in different fields of public finance, taking into account the

problems experienced on a global scale. The inclusiveness of public finance has

brought together eighteen different studies in this book, including theoretical, methodological

and empirical studies about various taxation problems such as COVID-19

and fiscal policies about healthcare system, financial incentives and biomass energy

worldwide, effect of tax wedge on inflation, and the evaluation of the problems in

international tax law; also digitalization and cryptocurrencies and the social effects

of taxation. The authors of chapters present some new models and policy suggestions

in their studies.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the editors

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- List of Contributors

- COVID-19 Crisis and Fiscal Policies to Strengthen the Healthcare System (Meral Fırat)

- Evaluation of the Impacts of COVID-19 Pandemic and Pandemic-Related Public Policies on the Labour Force and Entrepreneurship in Turkey (Şerif Emre Gökçay)

- Metropolitan Municipalities with Disaster: Covid-19 Pandemic and Ankara, Bursa, Diyarbakır and Manisa Metropolitan Municipalities Example (Hakkı Sağlam)

- Evaluation of the Effects of Technology Literacy and Digital Financial Literacy on the Investment and Taxation Process in Crypto Assets (Burçin Bozdoğanoğlu)

- International Tax Problems (Ali Erol)

- Current Situation in Turkey in Terms of BEPS Action Plan 13 Regarding Documentation Scheme in Transfer Pricing (Filiz Keskin)

- Evaluation of Active Participation of NGOs in Decision-Making Processes in Turkey in Terms of Relevant Legislation (Erdal Eroğlu and Adnan Gerçek)

- Financing of Higher Education in the World and Turkey (Fatih Karasaç)

- The Relationship between Government Expenditure and Trade Liberalization in Fragile Five (Göksel Karaş)

- Financial Incentives and Recommendations for Biomass Energy in Turkey, the USA, Brazil, and China in the Context of Sustainable Energy (Ayşe Yiğit Şakar)

- The Effect of Tax Wedge on Inflation (İhsan Cemil Demir and Rabia Tuğba Eğmir)

- Modeling of Taxpayers’ Resistance to Revenue Administration: A Different Approach to Tax Compliance (Adnan Gerçek, Güneş Çetin Gerger, Çağatan Taşkın and Feride Bakar Türegün)

- Measuring the Fiscal Illusion Trends of Municipalities in Turkey: An Empirical Study (Mehmet Öksüz and Selçuk İpek)

- Measuring the Tax Gap in the OECD Countries: 2013–2017 Years (Esra Uygun and Adnan Gerçek)

- Tax Education for Students in Turkey: The Case of Secondary School (Yasemin Arıman)

- A Risky Taxwise Gamble: The Higher Revenual Persistence The Angrier Communal Resistance (Mehmet Alpertunga Avci)

- A Review on the Legal Character and Consequences of Recidivism in Tax Criminal Law After Law No. 7338 (Zinnur Tunç)

- Prostitution and Taxation: A Historical Perspective (Şahin Yeşilyurt)

List of Contributors

Mehmet Alpertunga Avci

Assoc. Prof. Dr., Atatürk University, Faculty of Law, maavci@atauni.edu.tr

Yasemin Arıman

Dr., yaseminariman@hotmail.com

Feride Bakar Türegün

Assist. Prof. Dr., Bursa Uludağ University, Department of Public Finance, feridebakar@uludag.edu.tr.

Burçin Bozdoğanoğlu

Prof. Dr., Bandırma Onyedi Eylül University, Department of Public Finance, burcindogan@gmail.com

İhsan Cemil Demir

Prof. Dr., Afyon Kocatepe University, Department of Public Finance, icdemir@aku.edu.tr

Güneş Çetin Gerger

Prof. Dr., Manisa Celal Bayar University, Department of Capital Market, gunes.cetin@bayar.edu.tr.

Şerif Emre Gökçay

Assist. Prof. Dr., İstanbul University, Department of Public Finance, emregokcay@gmail.com

Erdal Eroğlu

Assoc. Prof. Dr., Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart University, erdaleroglu@comu.edu.tr

Ali Erol

Assist. Prof. Dr., Kırklareli University, Department of Public Finance, ali.erol@klu.edu.tr

Meral Fırat

Assoc. Prof. Dr., Ïstanbul Aydın University, Department of Economics and Finance, meralfirat@aydin.edu.tr←7 | 8→

Adnan Gerçek

Prof. Dr., Bursa Uludağ University, Department of Public Finance, agercek@uludag.edu.tr.

Selçuk İpek

Prof. Dr., Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart University, Department of Public Finance, selcukipek@comu.edu.tr

Göksel Karaş

Res. Assis. Dr., Kutahya Dumlupınar University, Department of International Trade and Finance, goksel.karas@dpu.edu.tr

Fatih Karasaç

Assist. Prof. Dr., Kırklareli University, Department of Public Finance, fatihkarasac@klu.edu.tr

Filiz Keskin

Prof. Dr., İstanbul Arel University, av.filizkeskin@gmail.com

Mehmet Öksüz

Lecturer Dr., Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart University, moksuz@comu.edu.tr

Hakkı Sağlam

Assist. Prof. Dr., İstanbul Rumeli University, Department of Political Science and Public Administration, hakkisaglam@gmail.com

Çağatan Taşkın

Prof. Dr., Bursa Uludağ University, Department of Business Administration, ctaskin@uludag.edu.tr

Rabia Tuğba Eğmir

CoHE 100/2000 PhD Scholarship Student, Afyon Kocatepe University Social Sciences Institute, tugbaegmir@outlook.com

Zinnur Tunç

Res. Assist. Dr., İstanbul University, Department of Public Finance, zinnur.bobek@istanbul.edu.tr

Esra Uygun

Lecturer Dr., Tokat Gaziosmanpaşa University, esra.uygun@gop.edu.tr←8 | 9→

Şahin Yeşilyurt

Assist. Prof. Dr., Ankara Yıldırım Beyazıt University, Department of Public Finance, shnyslyrt@gmail.com

Ayşe Yiğit Şakar

Prof. Dr., Istanbul Arel University, Department of Business Administration, aysesakar@arel.edu.tr

COVID-19 Crisis and Fiscal Policies to Strengthen the Healthcare System

Abstract: This study investigated the dimensions of health financing needs arising in Turkey due to the COVID-19 crisis. It was explained what kind of fiscal policy should be implemented to strengthen the health systems with increasing financing needs. The study’s main purpose is to investigate how the health system financing in Turkey can benefit from fiscal policies to meet the cost of the COVID-19 crisis on health systems. In this context, in the first part of the study, after a short introduction about the importance of the subject in the second part, the economic effects of the COVID-19 crisis and the course of health expenditures were investigated. It has been observed that developing countries lag behind in overcoming the effects of the crisis due to their own structural problems. The crisis has brought up the need to increase the expenditures for health financing worldwide. Turkey has the lowest rate among OECD countries in terms of GDP ratio of health expenditures with 4.4 %. The third part has been researched how the financing of health services in Turkey is provided. The most important sources of financing are taxes, social security premiums, private insurance premiums, and out-of-pocket payments. In the research, it has been observed that this deficit, which the Social Security System has given deficit since the 1990s in Turkey, is covered by the financial transfer from the budget. The share allocated to the Ministry of Health from the central government budget for the last four years is nearly only 5 %. In the fourth chapter, in this case, the designs that governments can make on how to strengthen the health system with taxes, public expenditures, and subsidies using fiscal policy are explained. Examples of fiscal policies for health are taxes on tobacco, tobacco products, and alcohol, subsidies on certain food products, and tax incentives for health care purchases.

Key Word: COVID-19, Health Financing, Health Expenditures, Fiscal Policy

JEL Code: E62, H3

1. Introduction

Although the COVID-19 crisis occurred in the health sector, it affected the economies of many developed and developing countries. Against this crisis, ←11 | 12→which affected almost all countries in the world, governments implemented expansionary monetary and fiscal policies. Despite these support packages, global GDP contracted by about 5.5 % in 2020 (World Bank, 2021:4).

This crisis, which emerged in the healthcare field, has increased the importance of financial strengthening of health systems due to the increasing needs of households already facing financial difficulties for reasons such as access to health services and out-of-pocket health expenditures. One of the Sustainable Development Goals 2030 proposed by the United Nations in 2015 is to expand universal health coverage in access to health services and strengthen financial protection.

Since the Social Security Institution (SSI), which has an important place in financing the health system in Turkey, has been running a deficit since the 1990s, this deficit is covered by transfers from the budget. While this issue constitutes one of the major obstacles to the budget as an investment budget, it increases public spending and debt, leading to an increase in interest and inflation rates. Therefore, the importance of fiscal and economic policies to strengthen the health system has increased even more during this period.

This study consists of 5 parts. In the introduction part, the importance and scope of the subject are briefly explained. The second part investigates the economic impact of the COVID-19 crisis and the trajectory of health spending. In the third part, the financing of the health system in Turkey and the status of the health budget during the pandemic period are examined, and in the next part, the fiscal policies to strengthen the health system are explained. A general evaluation is made in conclusion, and suggestions are made.

2. Impact of the COVID-19 Crisis and Development of Health Expenditures

2.1. Impact of the COVID-19 Crisis

The COVID-19 outbreak began in China in December 2019 but soon spread to Europe and the United States. At the beginning of the pandemic, it was hoped that warm weather would protect many developing countries from the virus, but this hope has not been realized. There are still cases of infection in Africa, South Asia, and Latin America.

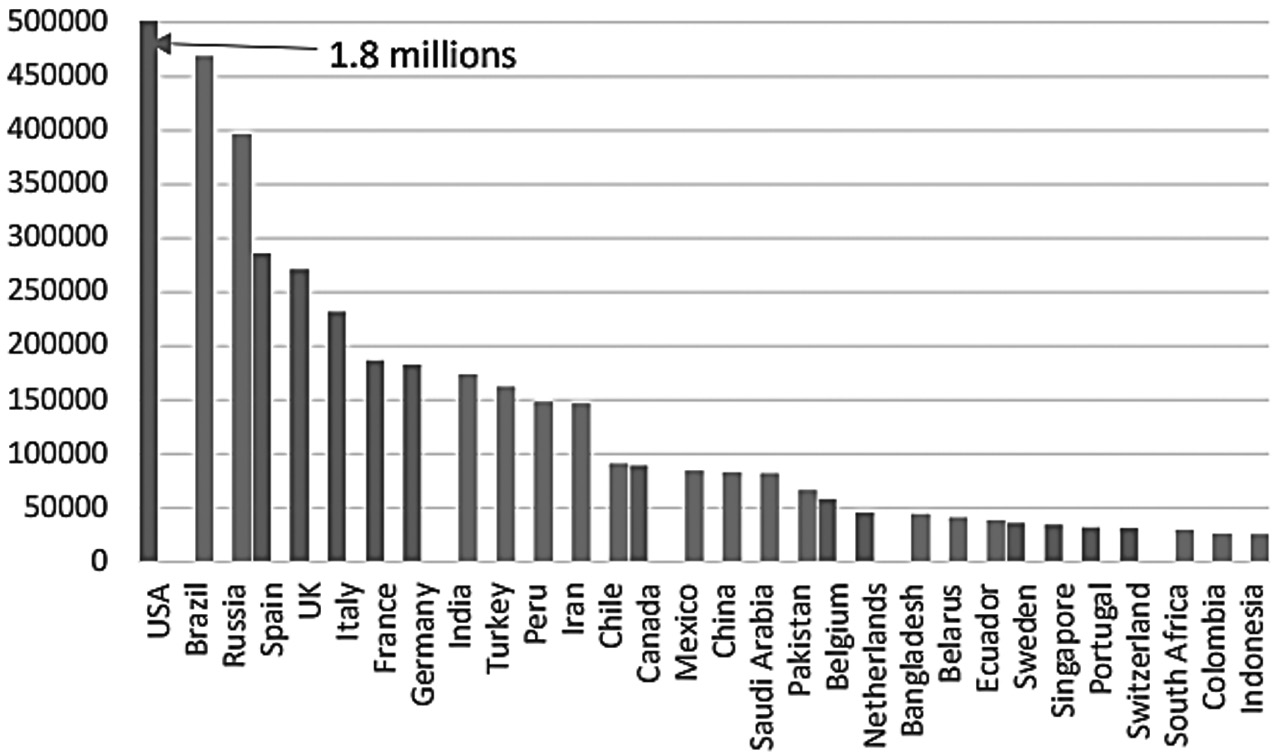

Figure 1:Number of reported COVID-19 cases (Top 30 countries)

Source: Centre for Economic Policy Research, COVID-19 in Developing Economies, Edited by Simon Djankov, Uga Panizza, CEPR Press, London,2020

←12 | 13→As shown in the red column in Figure 1, 17 of the 30 countries with the most reported cases were developing countries at the time of this study. This is not only because many developing and emerging countries have large populations.

Even developing countries with low infection rates have experienced large economic shocks related to the epidemic’s impact on commodity prices, capital flows, global trade, collapsing domestic demand, and tourism.

Developing and emerging market economies differ from advanced economies in the structure of their economies and the tools they can use to implement macroeconomic policies to reduce the magnitude and economic cost of the pandemic-related recession. The main differences are as follows (Centre for Economic Policy Research, 2020:9–10):

- – High levels of poverty and inequality existed before the pandemic.

- – Too many informal workers or workers in small businesses.

- – The size of the tourism sector in some countries.

- – The prevalence of civil unrest, violent riots, and civil wars.←13 | 14→

- – Relatively small public sectors and tax bases.

- – Limited fiscal space.

- – Insecure access to international financial markets.

As of June 2021, the number of people who died due to the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) has exceeded 3.7 million worldwide. The highest number of deaths is in the USA at 611 thousand and 20. USA with 467 thousand 706 deaths due to COVID-19, Brazil with 338 thousand 13, Mexico with 228 thousand 146, Peru with 184 thousand 942, England with 127 thousand 974, Italy with 126 thousand 283, Russia with 122 thousand 660, followed by France with 109 thousand 758, Colombia with 89 thousand 808 and Germany with 89 thousand 510. In Turkey, a total of 47,768 people lost their lives on June 2 (Dünya newspaper, 2021). Brazil followed the USA with 467 thousand 706, India with 338 thousand 13, Mexico with 228 thousand 146, Peru with 184 thousand 942, England with 127 thousand 974, Italy with 126 thousand 283, Russia with 122 thousand 660, France with 109 thousand 758, Colombia with 89 thousand 808 and Germany with 89 thousand 510 in deaths caused by COVID. In Turkey, a total of 47 thousand 768 people died on June 2 (Dünya Newspaper, 2021).

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted lives and impacted the global economy in all countries and communities. The pandemic has had a more significant impact on economic growth in 2020 than the negative impacts that have occurred in nearly a century. Recent forecasts show that the growth figures for the global economy will decrease from −4.5 % to −6.0 % in 2020 due to the pandemic. A partial recovery of 2.5 % to 5.2 % is expected in 2021. World trade is expected to decline to 5.3 % in 2020 and increase to 8.0 % in 2021. Economic growth in 2020 has not been affected as much as initially expected, albeit partially, due to governments’ monetary and fiscal policies. It is estimated that developed economies, which constitute 60 % of the global economic activity, will continue to operate below their potential until at least 2024, with negative effects on national and individual welfare. Compared to the global economic slowdown in the first half of 2020, while the advanced economies recovered in the last quarter of 2020, growth in developing economies has lagged behind (Congressional Research Service, 2021:2).←14 | 15→

The recovery rate in all regions and different income groups depends on developments in vaccine trials, economic support, and a number of structural factors such as tourism. The developed-country United States will reach pre-COVID-19 GDP this year. However, the other countries in the group will not reach pre-COVID-19 GDP ratios until 2022. Similarly, China, one of the emerging and developing economies, had already reached its pre-COVID-19 GDP in 2020, but many other developing countries are not expected to reach that number until 2023. Different recovery courses are likely to create significant differences in living standards between developing countries and others compared to pre-pandemic conditions. Cumulative per capita income losses in emerging and developing economies excluding China in 2019 are expected to be equivalent to 20 % of GDP, compared with pre-pandemic projections in 2020–22, while losses in developed economies are expected to be relatively smaller at 11 %. This matter has reversed the progress in poverty reduction. In 2020, 95 million people were projected to become poorer and 80 million more undernourished than before (IMF, 2021a:XIII).

The longer the epidemic lasts, the greater the burden on public finances. Public deficits and public debt have increased at an unprecedented rate, accompanied by a sharp drop in income due to the decline in production, and massive financial support has been provided. In 2020, the average fiscal deficit was 11.7 % in developed economies, 9.8 % in emerging economies, and 5.5 % in underdeveloped economies. In 2020, global public debt was 97.3 % of GDP, 13 % higher than the pre-pandemic forecast level. Central banks in developed and some emerging economies have cut policy rates and purchased government bonds to preserve their authority. Thus they facilitated the financial response to the pandemic. In 2021, fiscal deficits were expected to reverse due to the expiration of the support given due to the pandemic or reversal of the trend for expansionary policies and the influence of automatic stabilizers (IMF, 2021b:1).

2.2. Development of Health Expenditures

Although impossible to predict with certainty, the health and economic shocks triggered by COVID-19 will, directly and indirectly, affect health spending and progress toward universal health coverage. COVID-19 has had a destructive impact on global health systems. Since the health sector ←15 | 16→takes a minimal share of the budget, all countries have responded to the COVID-19 health and related economic crisis with exceptional budgetary allocations. Health budgets of low-income countries for 2020 have been disproportionately affected by the COVID-19 health response. The health crisis is indicated by a deep global economic crisis that may have a long-lasting impact on health financing.

In 2018, global healthcare spending reached $ 8.3 trillion, or in other words, 10 % of global GDP. This is the first time healthcare spending has grown more slowly than GDP in five years. Per capita, public health spending increased over the 2000–2018 period but grew more slowly after the 2008–2009 economic crisis. As a share of total healthcare spending, personal spending is over 40 % in low- and lower-middle-income countries. The decline in government revenues due to the economic crisis led many countries to take out additional loans (WHO, 202012).

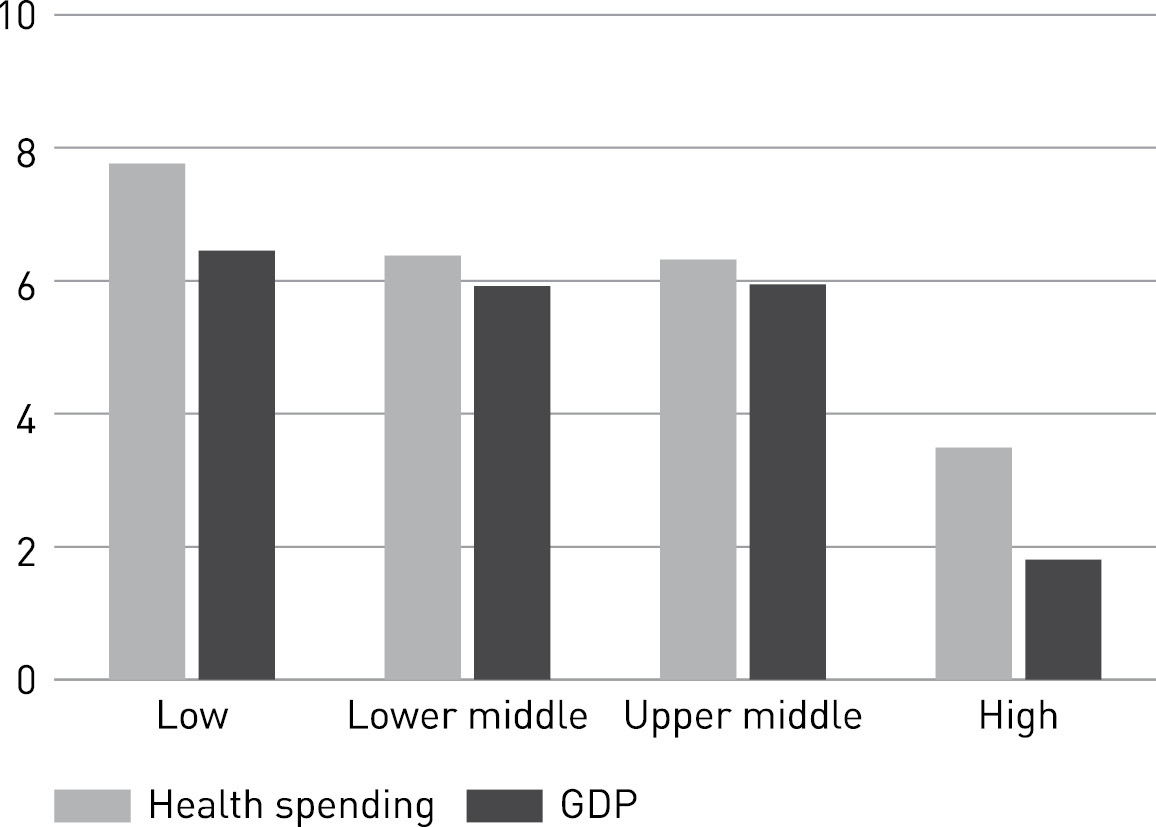

Figure 2:Health expenditures and GDP growth trends by country group (2000–2017 %)

Source: WHO, (2019), Global Spending on Health A World in Transition, p:6

Between 2000 and 2017, global healthcare expenditures grew by 3.9 % per year in real terms, while global GDP grew by 3.0 %. As shown in ←16 | 17→Figure 2, the increase in healthcare expenditures between 2000 and 2017 in low-income countries was 7.8 %, while economic growth was 6.4 %. While healthcare expenditures in middle-income countries are growing at more than 6 % per year, healthcare expenditures in high-income countries are averaging 3.5 % per year, about twice the economic growth rate.

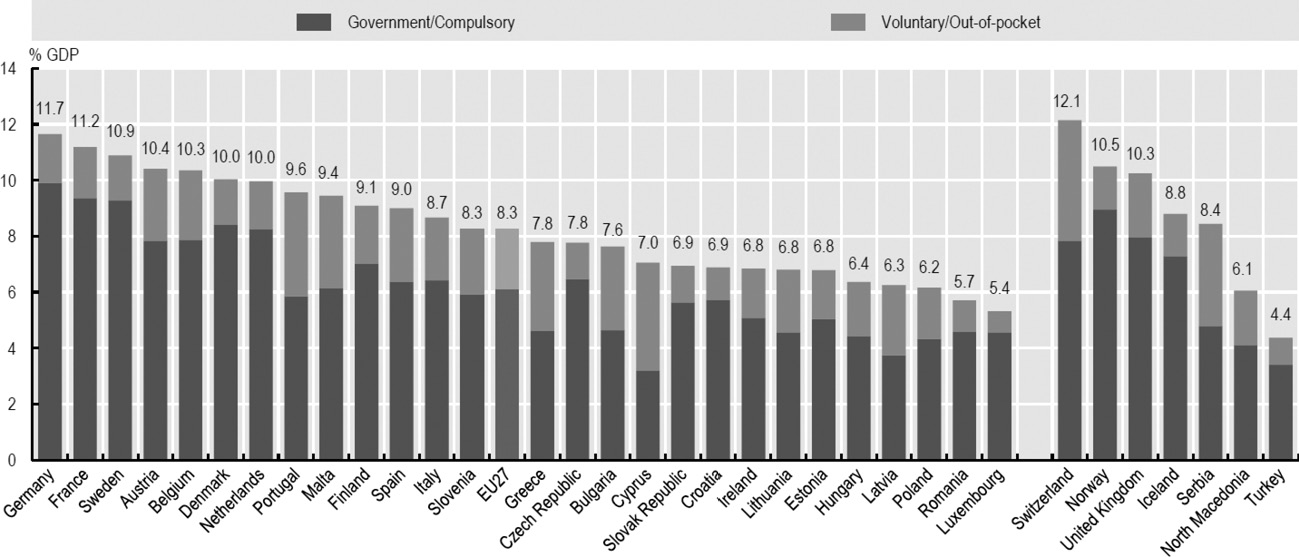

Figure 3:% of GDP Ratio of Health Expenditures in OECD Countries in 2019

Source: OECD, Health at Glance Europe 2020, p. 161, www.oecd.org

According to Figure 3, Switzerland has the highest health expenditure/GDP ratio among OECD countries at 12.1 %, while Turkey has the lowest health expenditure/GDP ratio at 4.4 %.

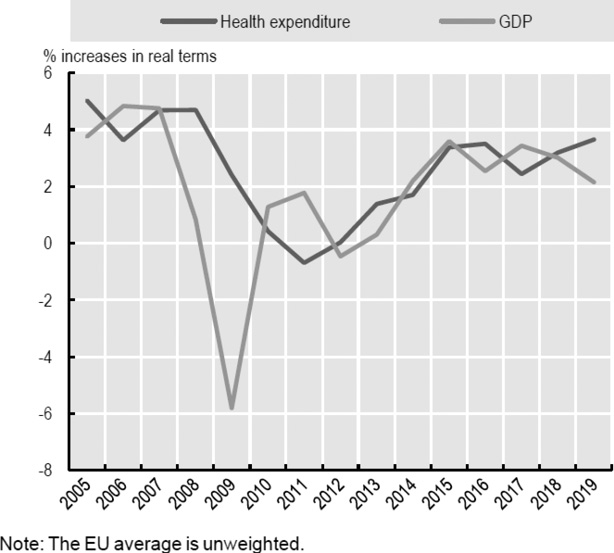

Figure 4:Health expenditure per capita and GDP Annual growth in GDP, EU27, 2005–19

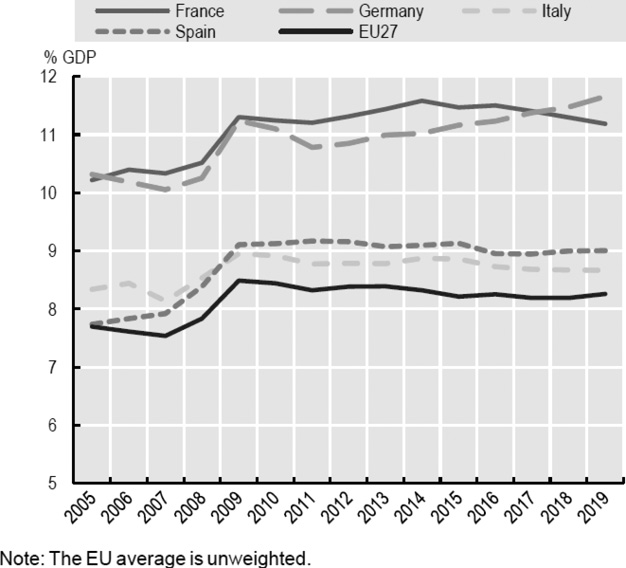

Figure 5:Health Expenditures/EU 27 and Selected Countries 2015–19

Source: OECD, Health at Glance: Europe 2020, www.oecd.org

←17 | 18→Figure 5 shows that EU countries will spend an average of 8.3 % of their GDP on health services in 2019. This figure has remained largely unchanged since 2014, as growth in health spending has been broadly in line with overall economic growth. In 2019, a quarter of EU member states spent at least 10 % of their GDP on healthcare, with Germany (11.7 %) and France (11.2 %) showing the highest shares. The lowest percentages of GDP spent on health services are found in Luxembourg (5.4 %), Romania (5.7 %), Poland (6.2 %), and Latvia (6.3 %). As shown in Figure 4, the average share of health expenditure in GDP in the EU-27 was over 8 % and is about twice as high as the share of health expenditure in GDP in Turkey.

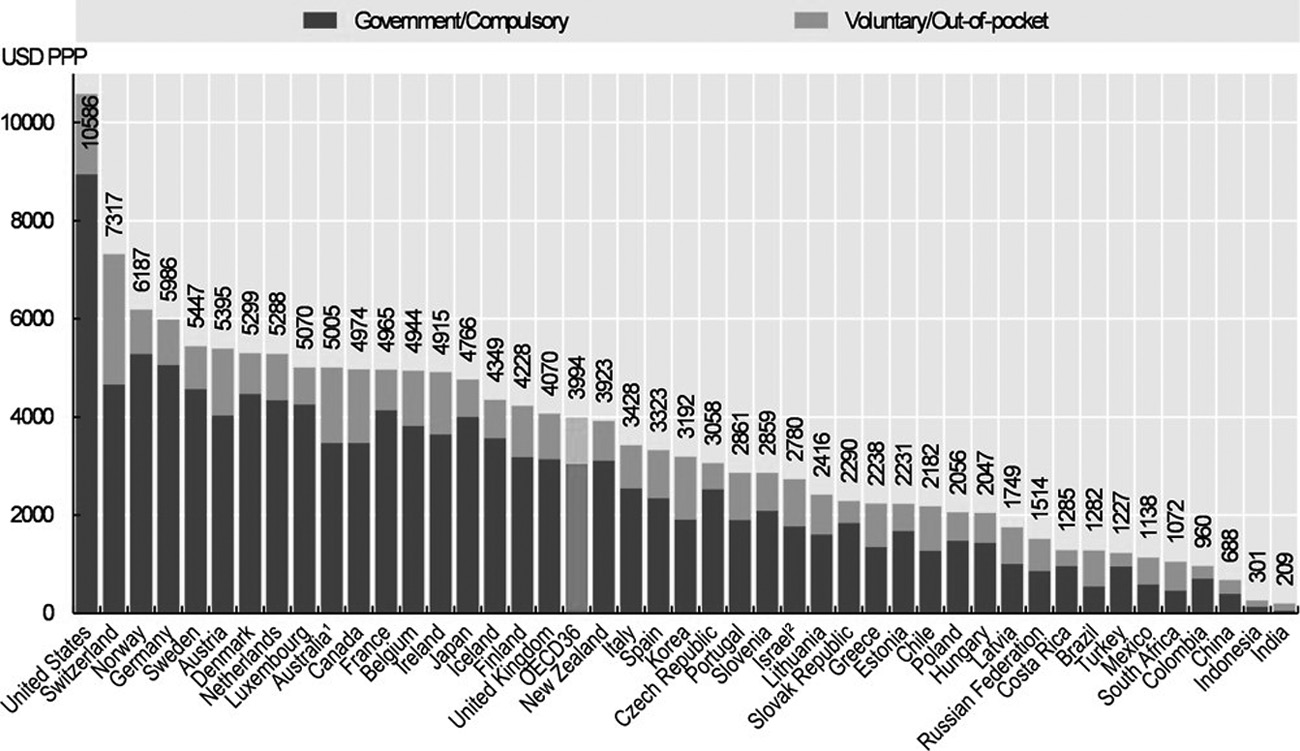

Figure 6:Healthcare Expenditure per capita 2018

Source: OECD, Health at Glance 2019: OECD Indicators, www.oecd.ilibrary.org

According to Figure 6, the USA is at the top of the table with 10 thousand 586 dollars in terms of health expenditure per capita in 2018. Switzerland follows the USA with 7 thousand 317 dollars and Norway with 6 thousand 187 dollars. The OECD average was 3 thousand 994 dollars. This figure is about four times the health expenditure per capita in Turkey. According to the 2020 Health and Glance report published by the OECD, the annual increase in health expenditures per capita in Turkey was 0.6 % between 2008–2013 and 3.2 % between 2013–2019 (OECD, 2019:151).←18 | 19→

3. Financing of the Health System in Turkey and the Status of the Health Budget in the pandemic

Today, countries have developed various health systems for financial purposes, such as ensuring a healthy life for their people and controlling healthcare expenditures. The main purpose of these systems is to manage and finance the resources for healthcare services. The main health system models implemented worldwide are as follows: The Beveridge model (National Health Service), in which healthcare services are fully financed from the public budget on a tax basis, and the Bismarck model (Compulsory Public Insurance), in which employees and employer deductions finance, the National Health Insurance Model, with private health care providers, run by the state and financed by the citizen through tax and premium payments, the out-of-pocket model, The US model based on private insurance, the Medical Savings Account Healthcare Financing Model, which is used for individuals, households, and institutions to deposit funds into their bank accounts in advance and for health expenditure only and the Turkish Model (Güngör, 2020: 4–7).

Theoretically, education and healthcare services are considered semi-public properties and services. Healthcare services in Turkey are public properties according to the Constitution of the Republic of Turkey. Healthcare is one of the functions of the state, and the Ministry of Health is responsible for healthcare services. Healthcare services are provided by public, semi-public, private, and non-profit foundations, and they are financed by taxes, social security contributions (SSI), private insurance contributions, and personal contributions. The Turkish health care system introduced the General Health Insurance System with the reforms of the last twenty years and the reform of the social insurance system that began in 2003. As a result of these changes, citizens were provided with access to health services, and the financial protection status of the low-income group was improved. As of 2012, all citizens needed to be included in the General Health Insurance System (Daştan and Çetinkaya, 2015:109).

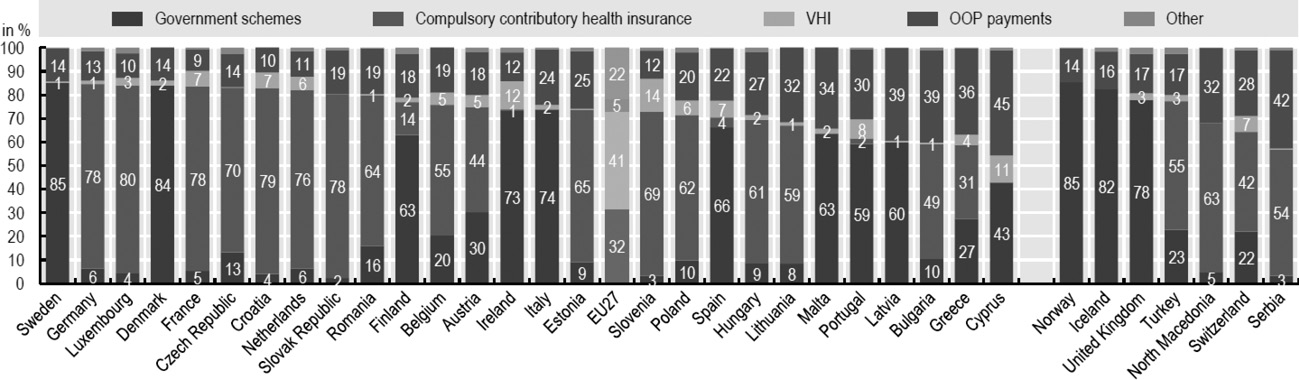

Figure 7:Healthcare Expenditures by Financing Type

Source: OECD, Glance at 2020, s:163

←19 | 20→As shown in Figure 7, the financing of healthcare expenditure includes both statutory health insurance and private funds such as voluntary health insurance and out-of-pocket payments from households, NGOs, and private companies. In 2018, around 73 % of health expenditure in EU countries was financed by state and statutory health insurance. In Sweden and Denmark, central, regional or local governments covered 85 % of all health expenditure. In Luxembourg, Croatia, Germany, France, the Slovak Republic, and the Netherlands, more than three-quarters of health expenditures were financed through statutory health insurance. Cyprus is the only EU country where less than half of all health expenditure is financed by public or compulsory insurance systems. It is expected that the national health insurance system introduced in 2019 will significantly increase this proportion (OECD, 2020:162)

Table 1. Total Health Expenditure by General State and Private Sector, 2018, 2019

|

(Million TL) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2018 |

Share (%) |

2019 |

Share (%) | |

|

Total Health Expenditures |

165.234 |

100.0 |

201.031 |

100 |

|

General State |

128.021 |

77.5 |

156.819 |

78.0 |

|

Central State |

40.461 |

24.5 |

51.492 |

25.6 |

|

Local Administrations |

1.439 |

0.9 |

1.373 |

0.7 |

|

Social Security Institution |

86.121 |

52.1 |

103.954 |

51.7 |

|

Private Sector |

37.213 |

22.5 |

44.212 |

22 |

|

Households |

28.655 |

17.3 |

33.626 |

16.7 |

|

Insurance Companies |

4.625 |

2.8 |

5801 |

2.9 |

|

Other |

3.933 |

2.4 |

4785 |

2.4 |

Note: Other healthcare expenditures include health care spending by non-profit organizations and other businesses that serve households.

Source: TurkStat, (2019), Health Expenditures Statistics

←20 | 21→As shown in Table 1, the ratio of total government health expenditures to total health expenditures in Turkey was 78.0 % in 2019, while the share of private sector health expenditures was 22.0 %. Looking at the sub-components of the state and the private sector, the social insurance institution had a share of 51.7 % in 2019, the central government 25.6 %, and households 16.7 %. Insurance companies accounted for 2.9 %, non-profits and other household businesses accounted for 2.4 %, and local governments accounted for 0.7 %.

Turkey’s social security system has been in deficit since the 1990s. Because of this, some important reforms have been made to make the system financially sustainable. The Unemployment Insurance Act, which came into force in 1999, introduced rules to increase the income of social security institutions and reduce their expenditure. In October 2003, Law No. 4632 on the Private Pension Saving and Investment System introduced the private pension system as a complementary model to the social security system. In 2006, with the Social Insurance Law No. 5602, Bağkur, the Law on Social Insurance, and the Pension Fund under the umbrella of the Social Insurance Agency, the various social insurance systems were combined in Law on Social Insurance and General Health Insurance (GSS) No. 5510. As a result of the reforms, the Turkish social security system is supported ←21 | 22→by two basic structures. These are the SSI and the Turkish employment agency. There is also the private pension system as a supplement. There is also the private pension system as a supplement (Cural,2016:695).

Table 2. Basic Indicators of SSI Incomes and Expenditures 2002–2020 (%)

|

Years |

Income Increase Rate |

Expense Increase Rate |

The ratio of Total Revenues to Cover Total Expenses |

The ratio of Premium Income Covering Pensions and Healthcare Payments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2002 |

49.8 |

56.9 |

71.5 |

61.0 |

|

2003 |

39.5 |

47.7 |

65.5 |

59.1 |

|

2004 |

24.3 |

22.5 |

68.5 |

62.6 |

|

2005 |

18.9 |

18.4 |

68.8 |

Details

- Pages

- 422

- Publication Year

- 2022

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783631882368

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783631883662

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783631883679

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9783631881675

- DOI

- 10.3726/b19913

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2022 (August)

- Keywords

- Digitalization and taxation Economic growth Public finance Tax expenditures Tax literacy Taxation

- Published

- Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Warszawa, Wien, 2022. 422 pp., 34 fig. b/w, 77 tables.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG