Branding «Western Music»

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- Branding “Western Music”: An Introduction (María Cáceres-Piñuel)

- Grooves of Empire: Internationalism, Imperialism, and Branding Western Music (Annegret Fauser)

- On the Need to Overcome Westernization and the Idea of Western Music: Towards a Post-Western Musical Scholarship (Anja Brunner)

- Forms of Value and the Rise of the Virtuoso (Timothy D. Taylor)

- Branding the German Lied: The Strategies of Julius Stockhausen (Natascha Loges)

- Spanish Guitarists in Early Twentieth-Century Germany: Negotiating Musical Identities in German-Language Guitar Magazines (Cla Mathieu)

- Symbolic Uses of Functional Musical Text in Late 19

- The Netherlandish School: The Construction of a Trademark (Petra van Langen)

- “Art Music Proper” in Changing Orchestral Culture: Two Case Studies of the Institutionalization of Finnish Musical Life in the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Century (Olli Heikkinen & Vesa Kurkela)

- Domesticating Continental Music Practices: Emergence of the Conservatory and Song Festivals in Finland 1880–1930 (Markus Mantere & Saijaleena Rantanen)

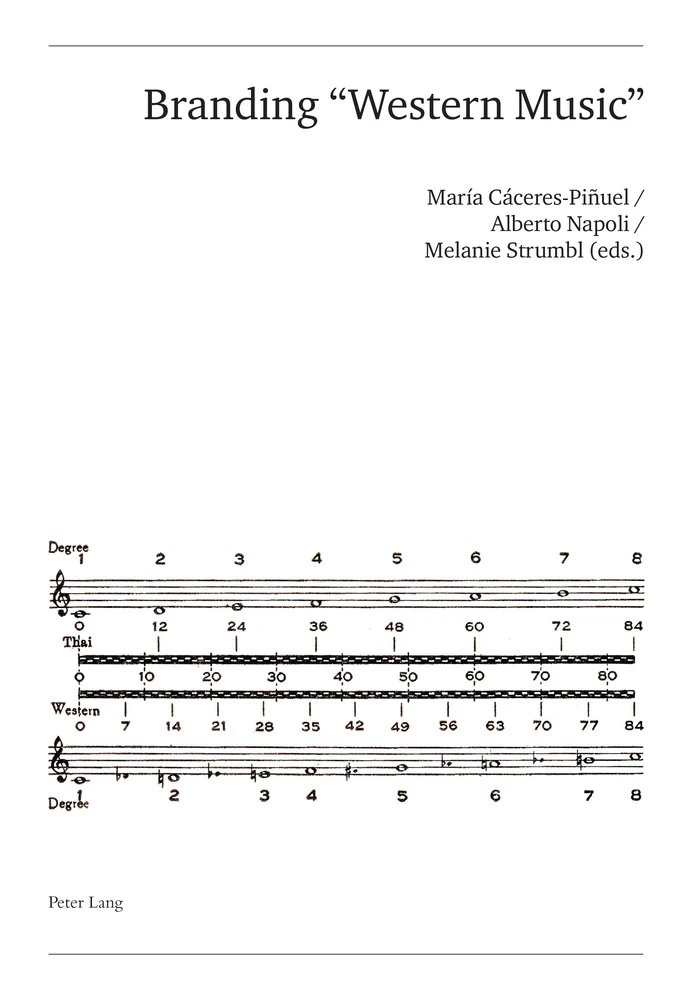

- The Transformation of Thai Music within Western Frameworks during the Thai Cultural Reformation in the 1930s (Siwat Chuencharoen)

- K-Classic: Branding Korean Classical Music (Meebae Lee)

- Programming the Record, Recording the Program: The Philadelphia Orchestra on Columbia Records, 1944–1946 (Mary Horn)

- Mass Classical: “Accessibility” and the Atlanta School of Composers (Kerry Brunson)

- Branding with Music and Music as Brand: Classical Music in American Television Commercials (Peter Kupfer)

- Biographies of the authors

- Biographies of the editors

- Appendix

Branding “Western Music”: An Introduction

María Cáceres-Piñuel

Origin of the book project

This edited book is a result of the Branding “Western Music” international conference that took place at the University of Bern in September 2017.1 However, this is not just a conference proceeding, since this book is a revised and blind peer-reviewed selection of the papers presented on that occasion. The conference was convened and organized by the research team of the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) interdisciplinary project, The Emergence of the 20th Century Musical Experience: Vienna 1892 (2015–2019), hosted at the University of Bern and led by Professor Cristina Urchueguía. The starting point of this project was an inquiry regarding the International Exhibition of Music and Drama held in Vienna in 1892. This event was the first and only music- and theatre-themed exhibition in the International Exhibition and World’s Fair series since 1851. Our working hypothesis was that Vienna 1892 represented the crystallization point of a modern conception of music as an aesthetic object and marketing product that shaped the “musical experience” of the 20th century in terms of creation, perception, and management. Our interdisciplinary research drew upon three complementary sub-projects developed by two PhD candidates and a post-doc researcher who took the Viennese exhibition of 1892 as a point of departure, but then developed their work beyond this initial stimulus. The common goal of our research was to investigate the role of International Exhibitions in the standardization and globalization of musical practices labeled as “Western” at the turn of the 20th century.2

The publication of this edited book has suffered various delays since the final manuscript was submitted to the publishing house in 2019. Finally, in 2022, a new Peter Lang editorial board led by Ulrike Döring, to whom I am very grateful, has taken detailed care of this postponed project. During this long editorial period, the editors, Alberto Napoli and Melanie Strumbl, former PhD candidates, and I, coordinator and post-doc researcher of the aforementioned SNSF project, have developed very different career paths in various venues. Alberto Napoli and Melanie Strumbl were engaged with this editorial project, and they supported me on this book’s editorial task during the project’s first years. Due to their various working duties, they could not accompany me in the last editorial period of this project. Still, their editorial imprint is tangible on almost every page. I also want to thank all the authors of this edited book for their patience with the editorial contingencies, and for their prompt reactions and enthusiasm with this publication.

State of the Art and Aims of the Book

According to Robert Jones, the history of branding shows it to be a commercial strategy, especially since the advent of capitalism, but it is also a practice that “implies ownership or heredity” (Jones 2017, 31). This book aims not to define the brand “Western music” that could indicate ownership as well as heredity, but to analyze the multi-fold branding processes of this cultural product. A brand endows a product with an aura or an ethos, or points to a provenance behind it. Quoting Jones’ words: “Branding, then, is a pervasive system of signs, associated with products, services, organizations, cultural products, places, people, even concepts…” (Jones 2017, 10). In the pages of this edited book, the reader will find some reflections on the economics related to how a set of repertoires, notations, discourses, and practices have been branded under the blurry notion of “Western music” and how this set of items has helped to sell other things in the world of publicity or diplomacy.

When we envisaged the “Branding ‘Western Music’” conference at the end of 2015, there was an increasing interest in researching music as a commodity. Some crucial books appeared just afterward on music and capitalism during the neoliberal era (Taylor 2016; Ritchey 2019), during our studied period (Bashford & Marvin 2016), and on the music industry of musical “classics” (Dromey & Haferkorn 2018). The intertwining between music and global economic processes has been extensively studied in the Anthropology of Music since the beginning of the 21st century (Stokes 2004; Baltzi 2005). Some of these studies focused on the global economic marketing strategies to sell the labeled “World Music” as an apposition or distinction of what was considered “Western Music” (Stokes 2012).

Even if the “Western music” concept is still common in standard and lay life, scholars have discussed its controversial connotations for decades, especially from Anthropology of Music and Ethnomusicology disciplines. There are a lot of attempts to explain why it is an inadequate, ethnocentric, and confusing term. There is also multi-fold research on the cultural imperialism and racism behind the term (Brown 2007). As an anecdote of the polysemy of “Western music” beyond musicological and ethnomusicological cenacles, I want to mention that we received a conference proposal that addressed the canonization of North American folk music in Western films. This proposal makes us consider the classist connotation and “high-brow” cultural depiction against popular genres, as Taylor pointed out in the case of the rejection of Western (popular) country genres within the common or lay conception of “Western music” (Taylor 2007). Indeed, many scholars have broadly studied how the “Western music” concept relates to power relations of supremacy, distinction, and exclusion (Born & Hesmondhalgh 2000). The term “Western music” also addresses a sort of canonization and a way to make history, not only for repertoires, but also related to practices, attitudes, and institutions linked to musical life and markets (Goher 2007; Taylor 2010). This book addresses different branding strategies of institutions, nations, and musical genre practitioners in order to belong to a supposed Western canon.

When we started to think about this book project, we saw an increase in voices claiming to relocate the history of “Western music” into a global scenario from an ethnographic perspective (Cook 2014) and defamiliarizing the West (Irving 2019). The resonance of the Balzan Musicological Project Towards a Global History of Music (2013–2017) led by Reinhard Strohm (Strohm 2018) also opened the discussion about the possibility of musicology adopting the discourses of global exchange (Romanou 2015). We aim not to advocate using “Western music” as a category, label, or analytical tool. However, due to its problematic connotations, it deserves to be analyzed from a historical perspective. By avoiding its use, we do not erase its pivotal conceptual role, especially for the past and current economies of music. Therefore, this ambivalent and, in some way, imperialist term helped us analyze musical branding processes.

Therefore, we have decided to use “Western Music” with quotation marks for the conference and the edited book titles because we never tried to use it as a category or univocal term. On the contrary, we are interested in analyzing the historical and cultural construction of the concept, focusing on how it was coined at the turn of the 20th century within the framework of international events. Hence, the adjective Western is not considered as a geographical, aesthetical, or cultural framing in this book project, but as a provocative term to invite the reader to retrace historical, musical, marketing processes from different local, social, and chronological perspectives. We proposed that the authors reassess the historical and multi-directional strategies in which the “Western music” concept has become a commodity or marketing label under different geographical and cultural contexts over the “long” 20th century.

Description of Book Content

This book brings together senior scholars, former PhD students, and post-doctoral scholars from different parts of the world. Most authors are specialists in Historical Musicology, but there are also researchers from other disciplines, such as Anthropology of Music, Gender Studies, and Sociology of Music. The chapters of this volume are split into four main interconnected sections that could serve as reading suggestions.

The first section, Clarifying Concepts from Historical Musicology and the Anthropology of Music, is the most conceptual. In this part of the book, Annegret Fauser and Anja Brunner discuss the framework and extent of the previously proposed discussion: the cultural construction and historical process of “Western Music” branding. Both scholars pointed out how the coining of the label “Western Music” is rooted in imperial and colonial scholarship thinking. Fauser, in her chapter Grooves of Empire: Internationalism, Imperialism, and Branding Western Music, demonstrates how Guido Adler, Edward J. Dent, and Henry Prunières returned to the ideal of internationalism as a core value of “Western music”. While those three musicological mobilizers negotiated a shared sense of constructing Western art music as the pinnacle of global artistic accomplishment, they were among the most influential and successful in forging the pathways of transnational scholarly circulation networking of a culture strongly shaped by imperialism. Brunner, on her side, in the critical text On the Need to Overcome Westernization and the Idea of Western: Towards a Post-Western Musical Scholarship, illustrates how power structures enacted throughout colonial history reverberate in how we view interactions and contaminations between different musical cultures. To define musical practices and repertoires resulting from the encounter of colonial empires and the colonized as “Westernized” is, for Brunner, an authoritarian and self-referential act practised by those who identify as “the West”, which is not necessarily reflected in how the colonized conceive of those practices. Ultimately, the problem lies in the label “West” itself, and Brunner advocates for abandoning such a term altogether.

The book’s second part, The Virtuosi Phenomenon as a Cosmopolitan Trademark at the End of the 19th Century: Agents, Genres, and Concert Practices, is devoted to the virtuoso market practices. This section comprises the chapters of Timothy D. Taylor, Natascha Loges, and Cla Mathieu. In his chapter Forms of Value and the Rise of the Virtuoso, Taylor, using Anna Tsing’s notion of “peri-capitalism” – non-capitalist forms of value that are produced outside of capitalism, that can be converted into capitalist value through processes of “translation” – demonstrates how supply chains can produce these seemingly non-capitalist forms of value that co-exist with capitalist forms, which he calls “para-capitalist”. To underpin his argument, Taylor presents a case study: the rise of the virtuoso in Western Europe in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century.

Natascha Loges, in her chapter Branding the German Lied: The Strategies of Julius Stockhausen, discusses how the baritone Julius Stockhausen (1826–1906), friend and colleague of Johannes Brahms, succeeded in shaping a public concert career performing the German Lied, a musical genre that was associated primarily with private, amateur performance. According to Loges, thanks to Stockhausen’s pioneering achievements during the second half of the nineteenth century, the idea of a professional singer dedicated to the performance of Schubert’s and Schumann’s songs was no longer absurd. By the end of the century, musicians and audiences had developed a distinct set of concert structures and conventions around the Lied. This chapter explores two aspects of how Stockhausen, as an artist, and the Lied, as a genre, attained some qualities of a brand. Firstly, she analyses the role of the musical press, and secondly, Stockhausen’s programming strategies together with Clara Schumann.

Cla Mathieu, in his chapter Spanish Guitarists in Early Twentieth-Century Germany: Negotiating Musical Identities in German-Language Guitar Magazines, discusses several guitar magazines published in Germany and Austria between 1900 and 1933. He turns his attention to questions of musical identities that were constructed around the guitar as a very popular instrument in Germany, and Spanish guitar virtuosos, hence, the contrast between the instrument being a means of a newfound German identity and also being an emblem of “Spanishness”. He also points out that, on the one hand, practices of “othering”, such as essentializing Spanish virtuosity and perceiving it as an inherently Spanish trait, were widespread. On the other hand, he shows that attempts were also made to establish the guitar as a popular German instrument. This chapter also deals with the economic aspects of Spanish guitarists’ concert tours and with German perceptions and discourses about Andalusian and Catalonian music. Mathieu’s text links in some respects with the book’s third section, devoted to different musical and national branding constructions and strategies around the concept of “Western”.

Titled Music and Nation Branding Strategies along the 20th Century: Notations, Repertoires, Discourses, Institutions, and Events, the third part of the book offers six case studies devoted to Greece, the Nederlands, Finland, Thailand, and Korea from the end of the 19th century to the current time of publication. In her chapter, Symbolic Uses of Functional Musical Text in Late 19th Century Athens: The Case Study of Antonios Sigalas, Artemis Ignatidou discusses Antonios Sigalas’ Collection of National Songs, a set of transcriptions in Byzantine neumatic notation, that was considered in 1880 as a work of national importance by the Greek state. This chapter examines how this collection became a statement against the trend of Western polyphony being considered at the same time as a symbol of nationalism and musical universalism at the turn of the 20th century.

In her chapter, The Netherlandish School: The Construction of a Trademark, Petra van Lagen focuses on a musical-historical definition, that of the Dutch School. Van Lagen highlights how such geographical definition changed over time and, according to different scholars, not only served a predictable nationalist agenda, but also established itself within an international community of scholars from different generations spanning over a century. According to Van Lagen, the flexibility of a geopolitical definition that could stretch and adapt to different understandings has made it particularly resistant to time, until today.

Details

- Pages

- 282

- Publication Year

- 2024

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783034346047

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783034346054

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9783034344555

- DOI

- 10.3726/b20075

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2024 (April)

- Keywords

- Music Economics Musical Targeting Musical Labeling Musical Imperialism Cultural Canonisation Programming Strategies Musical Nation-branding Music & Capitalism Music & Diplomacy

- Published

- Lausanne, Berlin, Bruxelles, Chennai, New York, Oxford, 2024. 282 pp., 4 fig. col., 4 fig. b/w, 13 tables.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG