Peace, Safety and Security: African Perspectives

Summary

This book, mainly based on empirical data, provides fascinating insights into the situation in Africa. The insights related to intra-national conflicts, civil strife, and peacekeeping initiatives, as well as explanations for gender-based violence, xenophobia, food security, cyber security, student insecurities, and hostel violence. The insights captured in individual chapters are primarily from early career academics, supported by more seasoned peers and colleagues. The trajectory in the culmination of this publication lasted almost painstakingly fruitful 24 months. The data and analyses presented in each chapter are nuanced but embrace the golden thread of Peace and Security in Africa. The fascination with the book is further enriched by the individual lenses through which each narrative is captured. The vastness of topics introduces fresh insights and perspectives to the orthodox understanding of Peace and Security.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- 1. Peace and Security Issues in Africa: Unearthing Trajectories in the 21st Century (George C. Mbara and Dasarath Chetty)

- 2. Assessing the Role Played by SADC and ECOWAS Regional Economic Communities in Maintaining Peace and Security in Africa (Simbarashe Tembo)

- 3. Exploring the Participation of Private Military and Security Companies in Civil War Scenarios in Africa (Nkosingiphile Mbhele and Mandlenkosi Mphatheni)

- 4. Explaining the Successes and Failures of UN Peacekeeping in Africa (Shalini Singh and Gargi Sharma)

- 5. The Role of African Victimology on Safety, Peace and Security in Africa (Lindani S. Nkosi, Mandlenkosi R. Mphatheni, and Simangele Mkhize)

- 6. The Impact of Globalisation on Occupational Health and Safety in Africa (Cynthia Z. Madlabana, Shanya Reuben and Ruwayda Petrus)

- 7. Understanding Cybercrime’s Morph from Computer-Based Fraud to Fetish-Based Spiritual Sacrifices: The Tale of Yahoo Plus in Nigeria (Sazelo M. Mkhize, Tolulope L. Ojolo, and Khanyisile B. Majola)

- 8. The African Union Peace and Security Council in the Libyan Uprising: An Afrocentric Perspective (Hlumelo Mgudlwa and Kgothatso B. Shai)

- 9. The Struggle to Contain Gender-Based Violence in South Africa (Shanya Reuben, Ruwayda Petrus and Cynthia Z. Madlabana)

- 10. Perspectives on Cultural Practices that Victimize Female Children in Africa (Ephraim K. Sibanyoni)

- 11. Inevitably Justifiable: Young Women’s Gender Based Violence Discourses and Evasion Strategies in ‘Sugar Daddy’ Relationships in a University Environment (Nolwazi Ngcobo)

- 12. Xenophobia against Foreign Nationals in Contemporary South Africa (Londeka Ngubane)

- 13. A critical Overview of Food and Nutrition Policies that Address Hunger and Malnutrition Amongst Children in KwaZulu-Natal (Sheetal Bhoola)

- 14. Student Insecurity: The #FeesMustFall Movement in South Africa (2015–2016) (Shaida Bobat and Fatima Essack)

- 15. Violence in South African Hostels: A Critical Review (Ntsika E. Mlamla, Philisiwe Hadebe and Khemist Shumba)

- 16. Understanding Cyberspace as a Security Threat: Perceptions of a Sample of South Africans (Nirmala D. Gopal, George C. Mbara and Sogo A. Olonfinbiyi)

- Epilogue: Peace, Security and Safety – A View from Outside (György Széll)

- Editor and Author Biographies

- Series Index

George C. Mbara and Dasarath Chetty

1. Peace and Security Issues in Africa: Unearthing Trajectories in the 21st Century

Abstract: Since the end of the Second World War, the total number of war deaths has been decreasing globally. In comparison with World Wars 1 and 2 modern conflicts have not seen anywhere near the rate of fatalities experienced during these catastrophic incidents of European barbarism in the 20th Century. Despite this trend, conflict and violence are on the increase, with many conflicts now including non-state players such as international terrorist groups, criminal organisations, resistance movements and political militias. The long-term drop in the fatalities of armed violence is visible in Africa, where, following the high that shadowed the conclusion of the Cold War, where imperialists used Africa as the battlefield for proxy wars, more wars ended than began. The African Union (AU) has worked to promote long-term development, peace and security, democratic consolidation, the rule of law, and human rights since its founding in 2002 with due regard to conflicts engendered by colonial antecedents. Although a few armed groups, such as Boko Haram and the Lord’s Resistance Army, operate regionally, most warfare in Africa nowadays occurs within states rather than as a result of war between countries. Consequently, through critical discourse analysis of secondary data with reference to relative deprivation theory (RDT), this study reflects on the peace and security trajectories in Africa in the 21st century. Findings indicate that while armed violence in Africa has gained prominence at the intra-state level, and the casualty rates have reduced, terror related crimes, kidnapping for ransom and civil resistance are on the increase in the urban centres and ungoverned territories. Poverty, population age structure, repetitive violence, democratisation, regime type, the bad-neighbour effect, and poor governance are all drivers of this trend identified in the literature. The cumulative interaction and impact of some or all these drivers results in a proclivity for violence.

Keywords: Africa, Coups, Peace, Security, Terrorism.

Introduction

The risk of violent conflict and political instability in Africa has been amplified by many structural pressures. Keys to conflict prevention, peacebuilding and development lie in understanding their nature, drivers, and trajectories (Bello-Schünemann & Moyer, 2018). The African continent has experienced several bloody civil wars over the last six decades. Some of the deadliest conflicts have ←7 | 8→ended. These include the Nigerian-Biafran War (1967–1970), the Congo Wars (1996–1997; 1998–2003), the Rwandan genocide (1990–1994), and the Ethiopian and Eritrean war from 1999 to 2000. The number of conflicts have, however, increased significantly in recent years (see the current Ethiopia-Tigray Civil War, 2020 – to date).

Internal strife in the 1990s presented the global community with an unfamiliar quandary: how could these prolonged crises be managed so that they did not result in the eruption or resumption of violent conflicts? While techniques of conflict management used during the Cold War, such as peacekeeping missions, continue to play a role, most conflicts in Africa today are not entirely military in nature, and cannot be addressed via military means only. In addition to other post-Cold War developments, growing international acknowledgement of the human cost of such intractable conflicts has led the global community to re-define security and its implications for policy planning. The idea of “human security” arose as a result of this shift in international security thinking. Human security covers new ground by looking at perceptions of security in a broader spectrum of human societies than that defined by the contemporary state, combining socioeconomic and developmental issues with acknowledgement of the importance of political stability. Human security may be defined as the protection and empowerment of people caught up in extreme violence and underdevelopment (Owens, 2012). The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) defined human security as both “safety from such chronic threats as hunger, disease and repression” and “protection from sudden and hurtful disruptions in the patterns of daily life. [UNDP], Human Development Report (1994). These definitions are complementary.

Threats to human security at the societal level are frequently the core causes of long-term internal conflict. To this end, this chapter outlines the trends and scope for peace and security issues in Africa and refers to relative deprivation theory to offer clues to understanding the current trends.

Relative deprivation theory

Samuel Stouffer proposed relative deprivation (RD) in 1949 as a post-facto explanation for some startling findings in his famous American Soldier series (Pettigrew, 2015). The American Soldier, a series of social-psychological studies on the American military services released in 1949, was the first to employ relative deprivation. This work, according to Fahey, was based on a significant corpus of research on factors impacting motivation and morale among US army troops conducted by the US War Department between 1941 and 1945. As a result, the ←8 | 9→idea of relative deprivation was established to explain how unhappiness among troops did not always stem directly from the objective problems they faced, but instead differed depending on how they framed their appraisals of their own position (Fahey, 2010). These evaluations were often based on comparisons they made between themselves and others who, while in different situations, were deemed to provide important reference points for self-evaluation (Fahey, 2010). The initial concept of the relative deprivation hypothesis, according to Walker & Pettigrew (1984), is simple: people may feel deprived of something good in comparison to their own past, ideal, persons, another person, group, or some other social category.

What began as an idea has gradually evolved into a full-scaled theory that is used across the social sciences to predict a wide range of occurrences (Smith, Pettigrew, Pippin, & Bialosiewicz, 2012). It has also become a significant contribution to the study of social justice (Smith & Pettigrew, 2015: 1) define relative deprivation as “a judgment that one or one’s ingroup is disadvantaged compared to a relevant referent, and that this judgment invokes feelings of anger, resentment and entitlement.” Relative deprivation arises when people compare themselves to those who have it better than them, they therefore conclude that their disadvantage is unfair. RD is useful because it explains why persons who should, by objective criteria, feel deprived often do not, and those who are not objectively deprived often believe they are (Smith & Huo, 2014).

People’s emotions, behaviour, and physical health change as their subjective expectations about what they deserve shift as a result of imposed or selected comparisons. The purposeful participation of a country’s populace in self-evident constructive endeavours is central to the core of good government. In Africa, relative deprivation and national instability are inextricably linked to the continent’s resource-rich, colonial history. The relative deprivation nexus of the continent’s insecurity problem does, in fact, profoundly touch on governance difficulties and resource control.

The Boko Haram disaster, according to Vybiralova (2016), also touches on relative inequality, with the sect members frequently pointing out the contrasts between common civilians and governmental elites or Christians perceived to be privileged by colonial practices. The oil industry had also degraded the ecology in the Niger Delta, and the region’s population have remained primarily impoverished (Asuni, 2009). As a result, while ethnic cleavages may still exist in the area, its residents are united by a sense of outrage at the region’s exploitation and neglect in relation to the rest of the country. Particular reference will be made to security developments in Africa in the post-Cold War era.

←9 | 10→Methodology

Content analysis and critical discourse analysis of secondary materials were utilised as research methods. This study reflects on the peace and security trajectories in Africa in the 21st century. By critically analysing existing texts on African security, the researchers were able to meet the study’s objectives. Critical discourse research, according to Van Dijk (2006) and Mogashoa (2014), is primarily concerned with and inspired by the desire to comprehend important societal problems. Critical discourse research, according to Wodak and Mayer (2009), emphasises the significance of multidisciplinary study to adequately understand the security trends in Africa. Critical discourse analysis is a long-term examination of underlying causes and consequences of situations. As a result, a detailed analysis of the connections between text, discourse, culture, and society is required.

Security trends in Africa

Since 1946, the total number of war deaths has been decreasing globally in relation to the 85 million lives lost during the Second World War. Despite this, conflict and violence are on the increase, with many conflicts now including non-state players such as international terrorist groups, criminal organisations, resistance movements and political militias. Scarcity of resources, illicit economic gain, absent or co-opted state institutions, a breakdown in the rule of law, and unresolved regional tensions, exacerbated by climate change, have all become major propelling factors of conflict (United Nations, 2020). Since the United Nations was created 77 years ago, the nature of conflict and violence has changed dramatically. Conflicts have become less deadly and more frequently fought between internal groups rather than countries. Homicides are growing increasingly common in some regions of the world, while gender-based violence is on the rise everywhere. Interpersonal violence’s long-term influence on development, especially violence against children, is increasingly becoming more well recognised. Separately, improvements in technology have sparked fears about the profileration of nuclear weapons and cyberattacks, as well as the weaponization of bots and drones and the livestreaming of terrorist assaults. There has also been an increase in criminal behaviour, such as data hacking and ransomware. In the meantime, international collaboration is strained, reducing the global capacity for preventing and resolving all types of conflict and violence (United Nations, 2020).

←10 | 11→In addition, new economic blocs, international treaties and commitments to economic development and peaceful coexistence have contributed to a peace trend. Clearly, fatalities between opposing countries’ armed forces, which are trained and prepared for large-scale fatal battle, result in far more losses than minor armed conflict incidents and internal wars, including those involving paramilitary or police forces (Bello-Schünemann & Moyer, 2018). The Middle East, the US invasion of Iraq and Afghanistan, the rebellions and western power interventions in Syria and Libya and the Russian campaign in Ukraine are seemingly exceptions to the general trend of reducing fatalities due to armed conflict in recent years.

The long-term drop in inter-country violence is visible in Africa, where, following the high that shadowed the conclusion of the Cold War, more wars ended than began (Dupuy et al., 2017). Although a few of armed groups, such as Boko Haram and the Lord’s Resistance Army, operate regionally across borders, most warfare in Africa nowadays occurs within states rather than as a result of war between countries. Five countries (Somalia, Nigeria, Niger, Mali, and Algeria) witnessed sustained activity from violent Islamist extremism in 2010, that number had risen to twelve by 2018 (Tunisia, Somalia, Algeria, Nigeria, Niger, Mali, Libya, Kenya, Egypt, Chad, Cameroon and Burkina Faso) (Africa Centre for Strategic Studies, 2018).

The number of civil wars in Africa increased from 18 in 2017 to 21 in 2018 – the highest number since 1946 – with 21 also recorded in 2015 and 2016. Furthermore, the number of countries with conflict on their territory has increased. Contrastingly, the number of battle-related deaths in civil wars has decreased since 2012, with approximately 6,700 people killed (Rustad & Vik Bakken, 2018). While the number of non-state conflicts in Africa has increased over the last five years, for the first time in ten years, the trend stabilized in 2018; the number of non-state conflicts has not increased. What are we to make of these apparently opposing trends?

As the number of conflict parties in Africa grows, conflict is becoming more complex. Extremist groups are more numerous, and they frequently break up into smaller organizations. The nexus between transnational organized crime and terrorism is increasing, and homegrown violent radicals in Africa have transferred their allegiances from al-Qaeda to the Islamic State in the Middle East (Alda & Sala, 2014). Political violence, such as riots, violence against civilians, and other forms of violence, are on the rise, and have recently been responsible for many more occurrences and casualties than in the past.

In Africa, political violence is predominantly urban-based, and future instability in the continent is more likely to harm cities and unpoliced and unplanned ←11 | 12→urban sprawls than rural areas (Commins, 2018). This is also true of extremist groups like Boko Haram and al-Shabaab, particularly when they utilize suicide bombers, a tactic that has become more prevalent in Africa. In 2011, Boko Haram began utilizing suicide bombers as a tactic, and in 2014, it began deploying female suicide bombers. In Nigeria, Cameroon, Chad, and Niger, the bulk of suicide bombs target civilians. Moreover, half of the bombers were women and children, some as young as seven years old, with over 60 occurrences involving bombers under the age of fifteen (Markovic, 2019). Female bombers were more frequently employed to target civilians, while male bombers were more frequently used to target government, police, and military formations. In Cameroon, female suicide bombers were employed more frequently, whilst male suicide bombers were used more frequently in Nigeria. Furthermore, girls were more likely to wear suicide belts or vests, although men were responsible for the vast majority of vehicle-borne suicide explosions. One of the deadliest threats to peace and security in Africa today is terrorism as can be seen in the following section.

Terrorism in Africa

Terrorism may be viewed as the calculated use of violence to create a general climate of fear in a population and thereby to bring about a particular political objective. Terrorism has been practised by political organizations with both rightist and leftist objectives, by nationalistic and religious groups, by revolutionaries, and even by state institutions such as armies, intelligence services, and police (Jenkins, nd).

When notions of terror are discussed, most people think only of particular geographies and countries, such as Afghanistan, Pakistan, Syria, and Iraq. Less discussed are African countries like Nigeria, where militants kidnapped 317 schoolgirls in February 2021 (Akinwotu, 2021). Headlines are rarely about Cameroon, Ghana, Chad, Kenya, Guinea, Mauritania, Burkina Faso, Mozambique, or Algeria. All these countries are experiencing an uptick in terror activity. The same applies to Mali where ten soldiers were killed in terror attacks in 2021 (Arslan, 2021); little attention is given to Niger, where at least 100 ordinary citizens were murdered in a terror raid in January (Agence France-Presse in Niamey, 2021). Many of them have become extremely dangerous areas, and it would be a mistake to presume that the problems they face have no influence on the rest of the world’s future security and stability.

Terrorist activities in the West African region is at an all-time high. Jihadists have dubbed it the “new battleground.” West Africa’s situation is exceedingly ←12 | 13→volatile. In Burkina Faso, 921,000 people have been displaced as of June 2020, with 593 persons killed. 240,000 people have been internally displaced in Mali, with 592 persons dead. In Nigeria, 1,245 have been killed while 489,000 people have been displaced (Gravitas plus, 2021). Jihadist terrorist groups are responsible for these fatalities and displacements. Most of these Jihadist groups have formed alliances with international terrorist organizations. Some are linked to the Islamic State, while others are linked to Al-Qaida, and all of them are continuously destabilising West Africa.

The pertinent question here is, how did they get started in Africa, and why are they succeeding? To begin with, Algeria gives one a sense of the situation. The Algerian military executed a coup in 1992 in order to thwart the Islamic Salvation Front’s quest to win the country’s first democratic election. Algeria was forced into a civil war by the Islamic Salvation Front, an Islamic political party, that lasted until 2002. During this time, about 200,000 Algerians died and 15,000 more went missing (Gravitas plus, 2021). Islamist fighters who had escaped from the country were among those who went missing. They took sanctuary in a sparsely populated region of northern Mali. The fighters reassembled their resources, collaborated with local rebel groups, and began indulging in criminal activities in these thinly populated areas.

These fighters reorganized themselves into a faction in 2007 and pledged their loyalty to Al-Qaeda. They were known as “Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb” (AQIM), which translates to “Al-Qaeda in the Islamic West.” The goal of this group was to topple Algeria’s government and establish an Islamic state. To accomplish this goal, the AQIM began collaborating with and funding a lesser militant group in Nigeria, the Boko Haram, which has already surpassed the Islamic State as the world’s most murderous terror group. Boko Haram literally means “Western Education is a Sin.” This organisation was formed in 2002 but gained global attention in 2009 when it became violent (Mbara, Uzodike, & Khondlo, 2019). Boko Haram received weapons from the AQIM. Boko Haram, on the other hand, had a different goal in mind: it wanted Nigerians to reject Western education, secular literature, and science. It began razing communities and murdering people to enforce its will. It kidnapped children and then utilised these kidnapped youngsters in suicide assaults.

Terrorists abducted 276 schoolgirls from a high school in Chibok, Bornu State, in 2013 (Akinterinwa, 2017). It abducted around 300 schoolboys from a boarding school in Katsina State in 2020 (Paquette, 2020), and 146 of the 362 passengers on Abuja-Kaduna train were kidnapped by Fulani-terrorist group in March 2022. Eight persons were killed in the attack, and 26 others injured (Sahara Reporters, 2022). It is a seemingly never-ending loop of kidnappings, as ←13 | 14→well as a never-ending circle of violence. Boko Haram has killed 37,500 people and displaced 2.6 million people since May 2011. It has forced 244,000 Nigerians to flee their homes into internally displaced persons (IDP) camps (Gravitas Plus, 2021). During this time, Boko Haram has also encouraged a number of Islamists to start their own terror groups. Nusrat al-Islam, the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group, the Islamic Movement of Nigeria, Ansaru, and Ansar-ul-Islam are among these groups. These gangs have become increasingly synchronized in their operations over the past six years, carrying out many attacks across Africa. Since 2014, these terrorist organizations have garnered numerous headlines. Two women and two children carried out suicide bombings in Chad in 2015 (Petesch, 2015), 16 people, mostly experts, were killed in the 2016 Grand Bassam shootings (‘Ivory Coast: 16 Dead,’ 2016). In Ouagadougou, two former Swiss Members of Parliament (MPs) were killed in the 2016 attacks (‘Memorial set for Swiss victims,’ 2016), and the French embassy was attacked in the 2018 Ouagadougou attacks (‘Jihadist group claims attacks,’ 2018). This is in addition to the numerous raids and crimes that these terror organizations carry out on a regular basis.

What could be the driving force for these militants? Is it merely a matter of religious beliefs and ideology? Yes and no. The issue is both pecuniary and religious in nature. Corruption, poverty and underemployment are all factors in this situation. The Lake Chad Region, one of the world’s poorest places, is where Boko Haram operates.

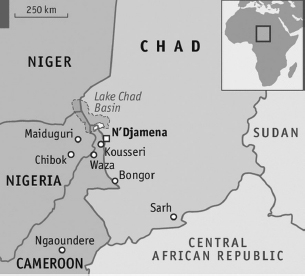

Fig. 1: Chad and its neighbours

Source: “Africa’s jihadists, on their way” (2014)

It is a part of the Chad Basin which has suffered severe ecological degradation and is geographically vulnerable. Likewise, the Sahel is a region with no stable governance.

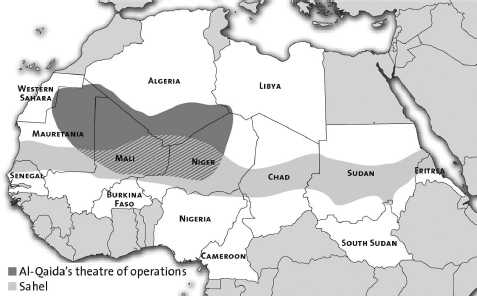

Fig. 2: Sahel region, Africa

Source: Centre for Security Studies Analysis in Security Policy (CSS), (2013)

The Sahel is a small strip of territory that runs from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Red Sea in the east. It is vast, scorching hot, and arid. It is also the world’s most abandoned geography, with an average temperature of 35°C. This has a significant impact on food production because there is nothing to grow and sell. Food shortages are common, and poverty is ubiquitous. The climate makes it an excellent breeding ground for terrorist organizations. These conditions make individuals susceptible to radicalisation. Boko Haram and the AQIM, for example, take advantage of this situation. They entice young men to pick up arms, join their ranks, and make a quick buck in the absence of governance and secure employment.

←15 | 16→How does Boko Haram accomplish this? What is their source of income? kidnapping for ransom, imposing taxes, looting banks and extortion are some of the methods used. According to Centre for Security Studies Analysis in Security Policy (2013), “In recent years, the number of Kidnappings for Ransom (KFR) has increased globally. Especially for Islamist terrorist groups in the Sahel, kidnapping has become a lucrative source of income.” Boko Haram was responsible for 26% of global kidnapping instances in 2013. According to the same research, the AQIM in Mali earned an average of US$ 5.4 million in ransom per hostage in 2011. This excludes high-profile kidnappings. In the same vein, the former US Ambassador to Mali, Vicki Huddleston, notes that France was forced to pay a $ 17 million ransom in 2010 to free four French people held hostage in Mali (CSS Analysis in Security Policy, 2013).

Terrorist groups have used kidnapping as a political tool since the 1960s. They mostly went after well-known people. The majority of the time, the goals were political, such as the release of prisoners, rather than financial. Kidnapping “ordinary” foreigners for the goal of ransoming them for money has only gotten more common in recent decades. Such criminally inspired kidnappings have previously been limited to individual countries such as Pakistan, Iraq, Mexico, or Colombia, and were thus considered as unique rather than a worldwide concern. That has altered in recent years, as evidenced by the rising frequency of kidnappings for exorbitant ransoms in the millions of dollars, such as those carried out by pirates off the coast of Somalia or targeted kidnappings of foreigners in Nigeria and Yemen.

The Covid-19 global pandemic struck when the terrorist groups were raking in the cash. For them, the year 2020 turned out to be a blessing in disguise. The pandemic confined most people to their homes, but it provided an opportunity for terrorists in West Africa to consolidate and proliferate (Gravitas Plus, 2021). Boko Haram already controls a vast area of land in Nigeria, and it is expanding its reach into Niger, Chad, Cameroon, Burkina Faso, and other countries of Sub-Saharan Africa in collaboration with other terror groups.

What is the international community doing about it? Former colonial powers seem to act only when their economic interests are directly threatened. France, which historically had colonies in West Africa, is the only country in the region that is actively fighting terrorism. It has dispatched approximately 5,100 military combatants to assist local troops in repelling terrorists. What is the reason for this? When it comes to West Africa, the majority of western countries have limited economic interests and are of the view that a supposedly remote threat prevails which will have little influence on the rest of the world’s future security. Armed interventions are conducted in Afghanistan, Syria, and other Middle ←16 | 17→Eastern countries in their quest for ideological hegemony and to protect geopolitical and economic interests.

The security situation in Africa has a direct impact on the rest of the world’s future security and stability. Although the African continent may not possess the same strategic importance as other regions at the moment, and it may not have the same quantity of oil, but Africa is the continent with potential because it accounts for 17% of the global population (1.3 billion people). It is expected that by 2050, its population will have nearly doubled to 2.2 billion people, with more than 60% under 25 years of age (Gravitas plus, 2020), half of the world’s gold supply, 90% of global platinum supply, 9.6% of the world’s oil output, 90% of cobalt supply globally, 2/3 of the world’s manganese supply, 35% of the world’s uranium supply, and 75% of the world’s coltan supply (Gravitas plus, 2021). Similarly, Africa accounts for 54 votes in the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) which reflects significant leverage on matters surrounding the UN Security Council (UNSC) reform and expansion (Mbara, 2019; Mbara et al., 2021).

The African continent is crucial to the global economy and to its security. But terrorists in West Africa are establishing new fronts in failing states. While the rest of the world looks the other way, they are expanding in every direction, posing a significant danger to Africa’s economic powerhouses. They can soon control or destroy these resources, putting Africa’s economy in jeopardy, with repercussions being felt around the world. This is so because the violation of human rights in the continent have long failed to sway world opinion towards meaningful intervention. The apparent lack of concern regarding security trends in Africa is something that requires far more serious analysis and intervention especially by those committed to non-violence, democratic participation and human dignity in secular societies. The next section unravels the drivers of these problematic security trends in Africa.

Resurgence of coups in Africa

Seven coups and attempted coups have occurred in African countries from May 2020 to February 2022. Military commanders succeeded in capturing power in Sudan, Mali, Guinea, Chad, and Burkina Faso; they failed in Niger and, most recently, Guinea-Bissau. These coups have been dubbed “contagious” and a menace to the entire region. After a period of comparatively fewer coups after the Cold War, Africa is on a new security trajectory. With these events, the norm of armies not getting engaged in governance or seizing power has been violated. While the current spate of coups has certain traits and exhibits a “dispersion effect,” using the term “contagious” or “domino effect” to describe them is problematic ←17 | 18→because it is a broad phrase. The coup in Guinea does not belong in the same category as what happened in Mali or Burkina Faso. Despite certain similarities, such as regimes that are unable to deliver basic services to their citizens, corruption, and weak state institutions, the circumstances and mechanisms of recent coups and attempted coups are distinct.

After Ibrahim Boubacar Keta, former Malian President, was seized at gunpoint by government soldiers in August 2020, Africa’s current era of coups began. Although there are certain connections across the ensuing sequence of African coups, including as economic and political instability and poor democratic institutions, the individual conditions in each country are critical to explaining what happened – and what may happen next. The governments of Mali and Burkina Faso were contending with violent extremism in the Sahel from al-Qaeda and ISIS affiliates. Attacks by militant Islamist organisations in the region surged by 70% between 2020 and 2021, from 1,180 to 2,005. In both nations, this security concern has been used as a justification for coups (Loanes, 2022). In terms of ←18 | 19→the differences, the juntas in Burkina Faso and Mali have stated that the coups were triggered by insecurity and an inability to cope with threats from violent extremist groups. Both juntas are using the same justification, but the threat in Burkina Faso is more immediate (Loanes, 2022).

While terror groups are a big threat in many African countries, not every country that has recently witnessed a coup is grappling with a violent insurgency from terror affiliates. The recent attempted coup in Guinea-Bissau, for example, is one of dozens since the country earned independence from Portugal in 1974. The country has struggled to develop democratic institutions and traditions; for example, President Umaro Sissoco Embaló – who survived an unsuccessful coup attempt – was elected in 2020 following a controversial election that was still being evaluated by the country’s Supreme Court at the time. Last year’s successful coup d’état in Guinea, a distinct country bordering Guinea-Bissau, happened when President Alpha Condé amended the constitution and conducted a power grab that handed him a third term in office. Despite winning a democratic election in 2010 – the first in Guinea – his power grab, along with profound inequality and corruption, appears to have given the fuel for the military to stage a coup last September (Loanes, 2022).

Details

- Pages

- 374

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783631892770

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783631892787

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783631889701

- DOI

- 10.3726/b20345

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2022 (December)

- Keywords

- Sustainable Development neoliberal globalisation Peace and Security in Africa

- Published

- Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Warszawa, Wien, 2022. 374 pp., 13 fig. b/w, 8 tables.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG