The Apocalypse in Ireland

Prophecy and Politics in the 1820s

Summary

(David Dickson, Professor Emeritus of Modern History,

Trinity College Dublin, Ireland)

«The Apocalypse in Ireland: Prophecy and Politics in the 1820s is a tough-minded, archivally-rich, and admirably original examination of a phenomenon rarely discussed in Irish studies: the biblically-based prophetics that ran rampant in the Catholic population in the two generations between the early 1770s and the late1820s. These are associated with the figure of «Signior Pastorini» (Bishop Charles Walmesley) who read the Apocalypse of St. John in a distinctly anti-Protestant fashion. Dr Thomas Power convincingly documents the immediate depth of these sectarian etchings upon the Irish Catholic polity and suggests the possible long-term impact of their underlying sanguinary agenda.»

(Professor Donald Akenson, Queen’s University, Canada)

A commentary on the Book of Revelation entitled A General History of the Christian Church (1771), written by an English Catholic bishop contained a prophecy that predicted the destruction of Protestantism in 1825. Summarized in a broadsheet and widely disseminated in Ireland, the prophecy drew on a receptivity in Irish popular culture to apocalyptic change. Reinforced by folk religion, poetry and ballad, the prophecy generated high expectations among Irish Catholics that a complete overthrow of the social and political order was imminent. The prophecy was appropriated by the Rockite agrarian movement of the early 1820s to give potency and legitimation to traditional grievances. The vacuum created by the demise of the agrarian movement was filled by the Catholic Association and Daniel O’Connell who utilized the prophecy for the attainment of Catholic emancipation in 1829. Dissemination of the prophecy resulted in a rise in sectarianism and contributed to an exodus from Ireland of large numbers of Protestants thereby creating an Irish spiritual diaspora particularly in British North America. This book reveals how a misinterpretation of the passages from Revelation heightened sectarian fervour that left a lasting legacy.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- List of figures

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- List of abbreviations

- Introduction

- CHAPTER 1. Revelation: Tomorrow’s News Today

- CHAPTER 2. Reception: The Making of an Apocalyptic Moment

- CHAPTER 3. Proclamation: The Word is the Seed

- CHAPTER 4. Usurpation: The Gospel of the Mob

- CHAPTER 5. Annihilation: The Bugaboo Year

- CHAPTER 6. Reconfiguration: Pastorini Was Nothing to Me

- CHAPTER 7. Ascription I: Accommodating Heretics

- CHAPTER 8. Ascription II: Hemmed In

- CHAPTER 9. Lamentation: Ireland Is Growing Too Hot

- CONCLUSION. Prophecy is History

- APPENDIX I. Editions of The General History published in Ireland, 1790–1825

- APPENDIX II. Signior Pastorini’s Prophecy

- Bibliography

- Index

Figures

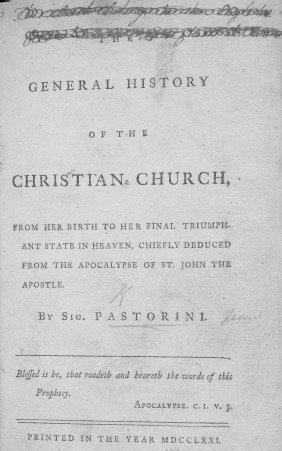

Figure 1 Title page of The General History of the Christian Church (1771). British Library Board.

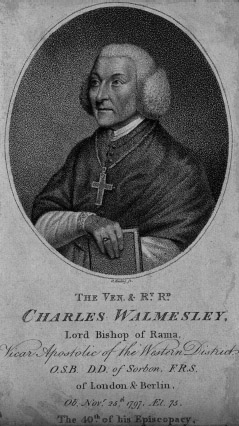

Figure 2 Charles Walmesley (1722–97).

Figure 4 Alexander Emmerich, Prince of Hohenlohe (1794–1849).

Figure 6 Signor Pastorini’s Prophecy (Dublin, n.d.). British Library Board.

Figure 7 Ballad singers from John Hand, Irish Street Ballads (Liverpool, 1875).

Figure 8 Prophecy man from The Irish Penny Journal, 12 June 1841.

Figure 11 Daniel O’Connell (1775–1847).

Figure 12 William Hales (1747–1831). Trinity College Dublin. University Art Collection.

Preface

For the most part capitalization and punctuation in citations from original sources have been normalized. Designation of Queen’s Co. (Laois) and King’s Co. (Offaly) are retained as consistent with the time period, as has Londonderry (Derry city). Individual placenames have been indexed under their respective counties. Translations from Irish not in the sources cited are my own. Footnote citations have been abbreviated for economy. Reference should be made to the Abbreviations and to the Bibliography.

Acknowledgements

I want to thank the following for assistance and kindness during the preparation of this book: Geoffrey Scott, Douai Abbey; Roger Boulter, Dublin; Donna M. Maguire, Scottish Catholic Archive, Edinburgh; Mike Maguire, Limerick County Library; Catherine Giltrap, Trinity College Dublin; Bethany Slater, National Army Museum; Jan Smith, Museums and Special Collections University of Aberdeen; Catherine Sider-Hamilton, Wycliffe College, Toronto; and colleagues and friends at Wycliffe College and the John W. Graham Library, Trinity College, Toronto. My thanks go to Tony Mason of Peter Lang for his helpfulness in seeing the project through. To my wife Marlene for her ongoing love, support and encouragement.

Acknowledgement is made for permission to reproduce the figures: British Library Board (Figures 1, 6), National Gallery of Ireland (Figure 10: NGI.2021.68), National Library of Ireland (Figure 5), the Board of Trinity College Dublin (Figures 9, 12), and John W. Graham Library, Trinity College, University of Toronto (Figure 13). All other figures are in the public domain.

Abbreviations

AH |

Archivium Hibernicum |

BCC |

Belfast Commercial Chronicle |

BL |

British Library |

Cambridge History |

The Cambridge History of Ireland Vol. 3 1730–1880, ed. J. Kelly (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018) |

CC |

Cork Constitution |

CECIM |

The Christian Examiner and Church of Ireland Magazine |

Chronology |

A New History of Ireland VIII A New History of Ireland VIII: A Chronology of Irish History to 1976. A Companion to Irish History Part 1, ed. T. W. Moody, F. X. Martin, and F. J. Byrne (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982). |

CSORP |

Chief Secretary’s Office Registered Papers |

DC |

Dublin Correspondent |

DEM |

Dublin Evening Mail |

DEP |

Dublin Evening Post |

DIB |

Dictionary of Irish Biography |

DMR |

Dublin Morning Register |

DWR |

Dublin Weekly Register |

FJ |

Freeman’s Journal |

FLJ |

|

GH |

The General History of the Christian Church from Her Birth to Her Final Triumphant State in Heaven, Chiefly Deduced from the Apocalypse of St. John the Apostle. By Sig. Pastorini. ([London: J. P. Coghlan], 1771). |

HC |

House of Commons |

HC, Disturbances |

House of Commons State of Ireland (Disturbances) 1825 (20), vii. |

HL |

House of Lords |

HL, Disturbances |

House of Lords, State of Ireland (Disturbances), 1825 (200), vii. |

IHS |

Irish Historical Studies |

IMC |

Irish Manuscripts Commission |

JEH |

Journal of Ecclesiastical History |

LAO |

Lancashire Archives Office |

NAI |

National Archives of Ireland |

NHI |

A New History of Ireland V: Ireland Under the Union I: 1801–1870, ed. W. E. Vaughan (Oxford: Clarendon, 1989). |

ODNB |

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography |

PRONI |

Public Record Office of Northern Ireland |

RCBL |

Representative Church Body Library |

SCA |

Scottish Catholic Archives |

SN |

Saunders’s Newsletter |

SOC |

State of the Country Papers |

TFP |

Tipperary Free Press |

WJ |

Westmeath Journal |

WM |

Waterford Mail |

All volumes in Geography Publications’ county history series have been abbreviated to the county name; for example, Limerick = Limerick History and Society: interdisciplinary essays on the history of an Irish county.

Introduction

In 1771 a volume was published entitled in part The General History of the Christian Church, by Charles Walmesley writing under the pseudonym ‘Pastorini’. This was an innocuous title, but the book contained a prophecy that, when repurposed, predicted the destruction of Protestantism in 1825.

The prophecy derived from the Book of Revelation. Because of its elusive apocalyptic symbolism and visions, Revelation proved eminently adaptable for those who, over the centuries, wished to utilize it to address circumstances in their own time. In the Irish context of the 1820s, Revelation lent itself to the selection of passages which allowed the sectarian dimension to predominate as its defining message.

Contrary to O’Farrell’s assertion as to the absence of millenarianism in Ireland, it existed and intensified from the 1790s to the early 1830s.1 The prophecy encountered a culture in Ireland receptive to divine intervention. It became popular because of its inherent appeal and because more traditional prophecies were proving inadequate in the more volatile decade of the 1820s when a high degree of expectancy for exponential change emerged. The more radical prophecy of Pastorini provided the script for the last days and the timetable for its achievement.

Cultural receptivity and wide dissemination accommodated adoption of the prophecy by rural protest movements creating a convergence of agrarianism and apocalypticism. With the decline of serious rural unrest by mid-1824, its apocalyptic dimension was transferred to the emergent movement for Catholic emancipation. Despite its importance, the role of the prophecy in the rise of O’Connell has not been acknowledged in standard treatments.2 Once achieved, Catholic emancipation in 1829 was viewed in millennial terms with O’Connell as the messianic deliverer.

←1 | 2→The relationship of the Catholic Church to the prophecy indicates that, on the one hand, it cautioned against its adoption because of an effort to confront an array of prevailing superstitions. On the other hand, while disavowal of the prophecy was consistent with a more rigorous pastoral discipline, the result of prophecy fulfilment – that is, the elimination of Protestantism – could not but appeal to an institution and a people seeking full civil and political rights.

Protestant response took the form of a mass exodus from Ireland to British North America. For Protestants, opportunities in the New World served to neutralize many of the inequities of the Old as the denominational imbalance was reversed, the political threat from Catholics negated, and viable Protestant communities emerged.

With the notable exception of Donnelly’s study of how the prophecy was embraced by the Rockites, Pastorini has been viewed as a marginal or eccentric addition to the main events of the decade.3 The merit of Donnelly’s treatment is that it delineates the potent convergence of agrarianism, sectarianism, and millenarianism. For Donnelly the sectarian factor adopted from Pastorini was uppermost as a motivating factor spurring the agrarian movement forward. It is apparent, however, that the prophecy continued as a force even after the agrarian movement was checked in mid-1824.

Others have downplayed Pastorini’s essentially sectarian message in preference to seeing alternative factors as causative. Irene Whelan emphasizes cultural and economic factors as contributory in the adoption of the prophecy. For Whelan, the utility of the prophecy as a phenomenon is that it provides ‘important insights into the cultural conflicts at work in Irish society at this time’.4 Thus Ireland fulfils the catalogue of elements identified by social historians and anthropologists as necessary preconditions for the adoption of millenarianism in colonial contexts.5 Explanations for the dissemination of Pastorini have focused on ‘relative deprivation’ and ‘disaster syndrome’.6 The economic and social downturn following 1815, the ←2 | 3→abandonment of Irish in favour of English, and the low point reached in the campaign for Catholic emancipation in 1815–22, are seen as contributory. These predispositions of deprivation coalesced around the failure of potatoes (1816) and the typhus epidemic (1817), both illustrative of the disaster syndrome.7 In Cork there was a conviction that the typhus epidemic was divine retribution.8 Deliverance from oppression and improvement in economic status are identified as the chief motivators in adoption of the prophecy.9 Such arguments propose that such adoption coincided with famine in 1821–22 in those counties most affected by the rural unrest, Cork and Limerick.10 Eschewing an overt sectarian cause, other historians have also emphasized natural disasters, detrimental economic conditions, and a politically turbulent context as reasons for the rise of millennialism.11

There is plentiful evidence, however, that the prophecy was more broadly embraced because it promised deliverance from oppression rather than issuing from mere deprivation. While, on the one hand, the colonial context is validated as a source for Irish millenarianism in the 1820s, on the other, it is dismissed in favour of the religious factor.12 It is conceded that the Catholic lower orders were seeking deliverance from their enemies not primarily because they were English in origin but because they were Protestant.13 This sectarian purpose drew not merely on the particular circumstances of the post-1815 context, but also on a long tradition of animosity and expectation in popular culture.

For some scholars, Protestant fears were unrealistic and contrived, and ‘fuelled in part by rumours’.14 The explicit anti-Protestantism of ballad and poem, largely inspired by Pastorini, is represented merely as a matter of ‘great irritation’ to Protestants.15 Historians more sympathetic to Protestantism, ←3 | 4→however, acknowledge the deep fears the prophecy generated. Bowen, for instance, contends: ‘The evidence is overwhelming that most Protestants, most of the time –and particularly at certain times, like 1825, the year of Pastorini’s prophecies – were not only anxious, but actually fearful of a sudden storm directed against them by the priests and people under their influence.’16 However, he does not elucidate the nature, depth, or full implications of such fears.

Ireland changed radically in the 1820s. Traditionally, interpretations of change have centred on Catholic emancipation, denominational relations, shifts in the Irish economy, rural unrest, population growth, and emigration. This book is not about these issues specifically, rather it explores how the prophecy infused and influenced them to an unappreciated degree. It demonstrates how a simple prediction fissured out to potent effect and how its visceral sectarian dimension became predominant. Thomas Moore, in lamenting the decline of theatre in Ireland in the post-Union era, depicted the transition as being from Shakespeare to the ‘often announced tragedies of Pastorini’.17 This book is about how that tragedy unfolded, with long-term consequences for Ireland and the Irish diaspora.

1 O’Farrell, ‘Millennialism’, 45–68.

2 Geoghegan, King Dan; MacDonagh, O’Connell.

3 Donnelly, ‘Pastorini’, 102–39; Donnelly, Captain Rock, 119–49. For a useful survey, see Colgan, ‘Prophecy’, 209–16.

4 Whelan, Bible War, 144.

5 Ibid., 144–5.

6 Ibid., 144.

7 Ibid., 144–5.

8 Robins, Miasma, 41

9 Whelan, Bible War, 145.

10 Ibid., 145.

11 Akenson, Discovering, 341.

12 Whelan, Bible War, 144, 146.

13 Ibid.,146.

14 Ibid., 147.

15 Ibid., 213.

16 Bowen, Protestant, 132.

17 Quoted in Jordan, Bolt, ii, 453.

CHAPTER 1

Revelation: Tomorrow’s News Today

The prediction of the destruction of Protestantism derived from The General History of the Christian Church from Her Birth to Her Final Triumphant State in Heaven, Chiefly Deduced from the Apocalypse of St. John the Apostle (1771).1 Its author, Charles Walmesley (1722–97), was an English Benedictine monk writing under the pseudonym Pastorini. The work was an exegetical study of the Book of Revelation. This chapter examines the General History for the validity of its claims and calculations. It situates Walmesley as a figure of the Catholic Enlightenment with its focus on historical criticism, Newtonian science, and Lockean epistemology.2 It probes extracts in the broadsheet version of the prophecy. It identifies sections of Revelation more pertinent to the political and economic context of Ireland, but which were excluded so that, in preference, the sectarian content was accentuated. The origins of Pastorini’s prophecy will be explored with its predictions and potent appeal.

←5 | 6→The Book Opened

Charles Walmesley (Figure 1) came from a traditionally strong Catholic area, Lancashire, and was educated at Benedictine colleges in Douai and Paris, where in 1742 he attained an MA from the Sorbonne followed by a licentiate in theology and a doctorate in divinity. His scientific research, particularly in astronomy and mathematics, occasioned his election in 1750 to the Royal Society of Berlin and the Royal Society of London.3 He was appointed coadjutor vicar apostolic (a titular bishop without a diocese) in 1756, an office he succeeded to in 1770 and held until his death in 1797. An early interest in literature and science revived in this period, notably his passion for Newtonian science, which influenced his analysis of Revelation. He believed the predictions he outlined in the General History were confirmed when the Gordon riots of 1780 resulted in the destruction of property, papers, and the bulk of his library at Bath.4

←6 | 7→

Figure 1 Title page of The General History of the Christian Church (1771). British Library Board.

Two preliminary aspects of the work are worth noting. The first relates to his use of the alias Signor Pastorini. It was a pseudonym derived from the Italian word pastore (shepherd). The choice of ‘Pastorini’ was, therefore, appropriate for someone a year into his appointment as vicar apostolic. Second, it is significant that the work was titled a ‘general history’ indicating that it was not ostensibly a work of biblical exegesis, but one in which the Bible was applied to history.

The General History (Figure 2) exhibited an intellectual dependence on two main sources: Newtonian science and the Catholic exegetical tradition. Walmesley was one among several Catholic scholars in the eighteenth ←7 | 8→century who were eager to modify Thomistic scholasticism through an engagement with or synthesizing of Protestant Enlightenment authors, notably Locke and Newton. Newton’s discovery of a mechanical universe that operated according to unchanging laws constituted a novel approach when applied to the study of Scripture. Newton believed he could reveal the mysteries of Revelation in the same fashion as he had demonstrated for the physical universe, that is, through the application of laws. The result, he hoped, would be to reveal the mysteries of time and history with mathematical precision. The code thus uncovered, Newton believed, could be related to events in history and the contemporary world. While Newton applied this method to Revelation, the result of his analysis remained unpublished, appearing only in 1733, twelve years after his death.5 Although Newton’s work was not highly original in that he borrowed from the work of Joseph Mede, the uniqueness of his contribution consisted of establishing a scientific approach to the text, a method whereby the exegete sought harmony in the parts and a simplicity of the elements, as Newton had discovered in the physical universe.6 It was a methodology adopted by Walmesley.

←8 | 9→

Figure 2 Charles Walmesley (1722–97).

Walmesley was also influenced by the French Catholic exegetical tradition of the seventeenth century. To appreciate the significance of this influence, one needs to situate it in the context of the four basic schools of interpretations of Revelation that existed over the centuries.7 First, the historicist school viewed the book as an inspired prediction of human history and, as such, its symbols described different periods of history and can be used to predict an end-time. Historicists saw the book as describing a long series of events from the time Revelation was written to the end of history and hence were prone to date setting. Second, futurists saw all but a few sections of the book as concerned with what will transpire at the end of ←9 | 10→time beyond the current age and that no prophecy has to be fulfilled before Christ’s second coming, hence they looked forward. Third, the preterist view saw Revelation as describing the time in which it was written, that is, the first century and hence most of the events described have already taken place. Finally, the idealist view regarded the book as devoid of any predictions of the future for it contained symbolic word pictures meant to convey spiritual truths.

Catholic exegetes of the sixteenth century adopted a futuristic view of Revelation, but by the time of Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet (1627–1704), an historicist view prevailed. Dismissing literal and moral interpretations that previously prevailed, Bossuet advanced an historical interpretation, particularly as it applied to the first Christian centuries.8 Second, the exegetical approach espoused by Bossuet was one whereby he eschewed verse-by-verse analysis in preference to discerning general religious themes in the text, its potential to prove dogma, and the identification of passages where the message was clear rather than struggling with difficult passages where it was not.9

In contrast to this historicist approach, Walmesley cited Augustine’s City of God (Book 2, c.8) approvingly, as depicting Revelation as a prophecy of what was to happen between the first and second comings of Christ. As such it was a summary of the history of the Christian church from its birth to its state in heaven after the end of time.10 In adopting this interpretation, Walmesley was necessarily dismissive of Bossuet in his L’Apocalypse avec une explication (Paris, 1689) and Walmesley’s fellow Benedictine and near contemporary Augustin Calmet (1672–1757) who in his Commentaire littéral (Paris, 1726), represented Revelation as applicable only to the first four centuries. Instead, Walmesley validated such commentators as J. Trotti de la Chétardie, Explication de l’Apocalypse (Bourges, 1692) and L’Apocalypse expliqué par histoire ecclésiastique (Paris, 1701) who regarded the book as extending beyond those centuries.11 In particular, Walmesley adopted the model advanced by de la Chétardie who divided the Christian era into ←10 | 11→seven periods corresponding to the seven seals, seven trumpets, and seven vials of Revelation.12

Complementary to this, Walmesley’s approach to the interpretation of Revelation, in common with Catholic and Protestant exegetes since the Reformation, was a literalist one.13 In particular, the General History drew on the work of prominent Catholic commentators who were concerned to provide a defence of the Catholic Church against the attacks of the Protestant reformers, though Walmesley sought to extend their interpretation by deploying the tools of Newtonian science.14 This combination of old and new gave the General History a unique status as a work of the Catholic Enlightenment. However, the convergence between Newtonian science and the Catholic exegetical tradition was too great a compromise for more mainline Catholic scholars to accept.

Even though it employed scientific rationalism, Walmesley’s use of it was not unequivocal. Though indebted to Newtonianism, the General History demonstrated a concern for the destructive effects of contemporary reliance on reason resulting from the secular Enlightenment. This latter attitude contrasted with an early enthusiasm for reason exhibited by many Catholic intellectuals, Walmesley among them. From this disenchantment with Enlightenment ideals came a realization that the conflict between good (as represented by Catholicism) and evil (as epitomized by Enlightenment reason) had been predicted by Revelation.15

From his analysis Walmesley discerned elements of continuity in Christian history, with the Reformation constituting an aberration and temporary disruption. Thus, Protestants were a deviation from the one true church, whereas for Protestants the Reformation marked the beginning of a new era in which God’s plan for humanity was to be fulfilled. Appreciation of the element of continuity also allowed Walmesley to build on a model of past and present to predict what would happen in the future.16 In all this he dispensed with the heavy textual commentary with which earlier ←11 | 12→works of the kind were layered, and instead supplied an applicability to the contemporary church which appealed to readers.

In common with Newton’s approach to interpreting Revelation, Walmesley focused on the meaning and application of certain elements, that is, successive severing of seals, the blowing of trumpets, and the pouring out of vials, which he used to determine the succession of historical events in the book.17 Walmesley believed that his own era was the fifth age of the church, and was divided into two: one period stretching from 1525 to 1675 when Protestants unleashed the Reformation on Catholics; and the other from 1675 to 1825 when the persecution of Catholics continued, resulting in defections to Protestantism, and at the conclusion of which the sixth age was to begin.18

Details

- Pages

- XX, 494

- Publication Year

- 2022

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781800799042

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781800799059

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781800799028

- DOI

- 10.3726/b19834

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2022 (November)

- Keywords

- Apocalypticism and trauma Spiritual diaspora Prophecy and sectarianism The Apocalypse in Ireland Prophecy and Politics in the 1820s Thomas P. Power

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, New York, Wien, 2023. XX, 494 pp., 13 fig. b/w.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG