Julian of Norwich in Her Phenomenology

Her Spiritual Texts and Their Historical Contexts

Summary

(Julia Bolton Holloway, Hermit of the Holy Family, Florence)

«A new work on Julian of Norwich is always a cause for celebration and Dr Clemmer's book is no exception. The reader is enabled to follow Julian closely before, during and after her unique visionary experience, examining contemporary history and spirituality from many angles. And the story continues right up to Edith Stein in the twentieth century. This book will delight all Julian lovers, as well as others who want to know Julian better and appreciate her in greater depths.»

(Sr Elizabeth Ruth Obbard ODC, Quidenham Carmel, Norwich)

Julian of Norwich in Her Phenomenology engages Julian’s primordial religious experience of May 1373; her subsequent definition to its revelation within her spiritual texts; and their hermeneutics made manifest from centuries of historical context. The meaning of Julian’s experience continued to unfold throughout her life: with its grace, and by insight with her own use of phenomenological method. The historical manifestation of Julian’s graced experience is given its closest phenomenological expression within her Short Text (Amherst) and in her Long Text (Sloane), with their collective human-Divine collaborations. But first, they arise phenomenally for Julian in the reciprocal gaze exchanged between her God and her soul. It is by God’s Trinitarian gift of love, and in her grace-filled collaboration with others, that Julian’s spiritual texts preserve, and guard, her experience of prayer and contemplation grounded in God: namely, with humanity’s resting in God’s substance, and with God’s resting and ruling in her own soul as God’s homeliest home.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

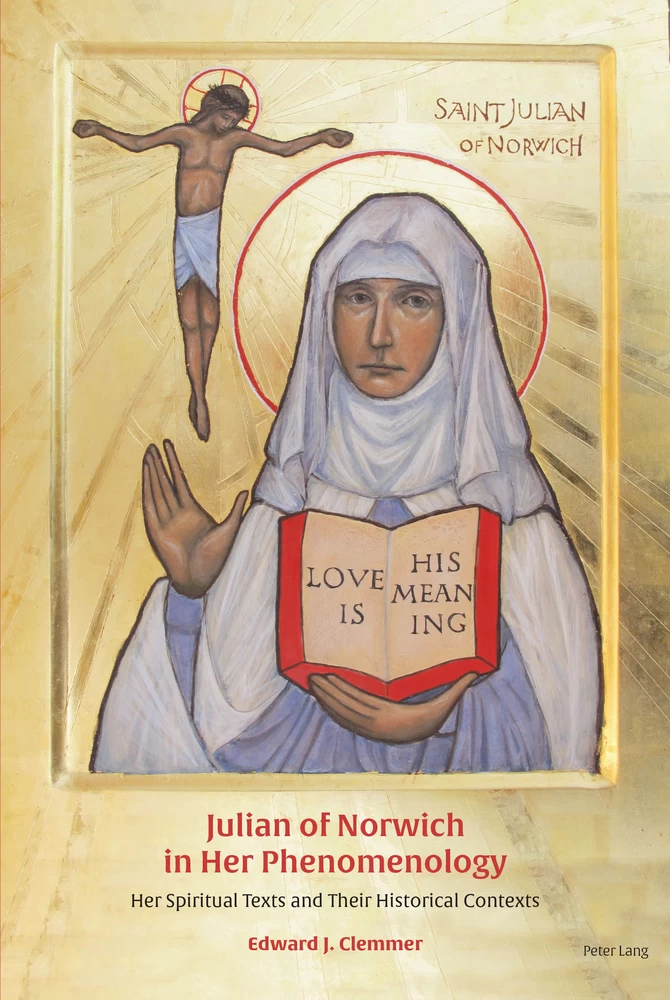

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- INTRODUCTION God’s “Revelation of Love” and Julian’s “Divine Gift to All”

- PART I Introduction to the Historical Julian of Norwich

- CHAPTER 1 The Historical Julian (up to and including 6 May 1373)

- CHAPTER 2 In Julian’s New Creation (her Nine Nights and Days in May 1373)

- CHAPTER 3 From Vision to Anchorite (from Sunday 15 May 1373 to c.1393)

- CHAPTER 4 The Politics of Church and State (1373–1393)

- CHAPTER 5 Walter Hilton and the Cloud author – and Julian’s Short Text (1380s–c.1393)

- CHAPTER 6 Julian’s Hidden Life in God’s Love, and Lollardy (1393–1418)

- CHAPTER 7 Julian’s Long Text: The Benedictine Nuns of Cambrai (1623–1651) and Father Augustine Baker, O.S.B. (1575–1641)

- CHAPTER 8 The Cambrai and Paris Benedictine Nuns (1651–1670) and Fr. Serenus Cressy’s “Mother Juliana” Long Text (1670)

- CHAPTER 9 Serenus Cressy’s Editions (1670–1902) and his Polemics with Edward Stillingfleet (1657–1672)

- CHAPTER 10 Julian of Norwich’s Critical Long Texts (1947–2016) and their English Translations and Modernizations (1877–2015)

- PART II The Short Text The Amherst Manuscript, British Library, Additional 37,790 Analytical Transcription and Annotation

- Preface to Part II

- Sections 1 – 25 Analytical Transcription and Annotation

- PART III Julian’s Long Text: Her Trinitarian Theology of Love

- CHAPTER 11 Julian’s Grace as Divinization: The Unity of Finite and Eternal Being

- CHAPTER 12 Julian’s Grace as Charity: Her Transformation in Prayer by Divine Love

- CHAPTER 13 Julian’s Grace as Faith: Life, Love, and Light

- Bibliography

- Index

INTRODUCTION

God’s “Revelation of Love” and Julian’s “Divine Gift to All”

Grace is our union with the life of God, with the essence of God’s eternal being. This aspect of participation in the Divine Life is the same for everyone who shares in grace. Grace is necessary for anyone’s eternal life with God, but grace is not the same for everyone. The relationship of grace to individual persons, according to the specific variation and beauty that distinguishes each soul, is unique by its nature and in God’s gifts, as every created person is clothed by God’s natural and spiritual gifts in the glory of God bestowed upon it. There is only one source of grace, Jesus Christ our justification. Often there are many opportunities and means for grace, as God always offers us his particular gifts. However, persons may and do refuse those gifts; as God also may withhold them, also in our choice that is sin. Even so, God’s mercy still may be extended to us. Julian of Norwich struggles with this mystery of redemption that pertains to her and to all God’s lovers – with the relationship of grace to sin, with the mystery of God’s love that purifies us by love and transforms us into love, also as God heals our wounds and makes us whole,1 in his fulfilment of our human nature.2

←1 | 2→God’s gift of grace to Julian of Norwich is captured within the phenomenology of her lived experience of revelation.3 For those who receive its call, the grace is already received and God reveals himself. As God gives and reveals himself to Julian, she in her necessary praxis also produces her texts.4 Julian’s processes for transposing her revelation experience into a spiritual text are given by pre-emergent grace, inceptional grace, and continuing grace: each grace the revelation of love, by God’s gift; and all is performed in Julian by love who transforms her, by that grace, into love. Grace leaves behind its evidence within Julian’s soul and throughout her texts, like the trails of ionization formed by nuclear matter in a cloud chamber, after the otherwise unseen event has long passed; as we may be allowed to observe this course of grace in her; and as we also may be called into grace by our participation with Julian in the ongoing spiritual dynamic, which has its origin in the Spirit of God, also with God’s gifts to us: “And from his fullness have we all received, grace upon grace” (Jn 1:16).5

←2 | 3→On an empirical level, our primary data and focus for analysis is Julian’s revelation experience, as it reveals itself in itself,6 as grace is made manifest within her spiritual texts. Jean-Luc Marion has provided us with a framework for the possibility of revelation,7 and for a contextualization of its saturated and paradoxical nature from a model for a phenomenology of givenness,8 which radical phenomenology we will take up, but towards describing Julian’s phenomenal experience within a theology of grace.9 Edith Stein provides a contemplative parallel to Julian of Norwich, as a mystical model in theory and spiritual practice. St John of the Cross provides further comparisons for Julian’s spiritual process, as Julian generally falls within the Carmelite spiritual model: the contemplative union with God, as God reveals himself to the soul, within the kingdom of one’s interior being, upon the threshold of heaven.

The phenomenological method, whose objective is to reveal and to reflect the “truth” from many angles,10 is at the centre of today’s theology of ←3 | 4→the Christian spiritual experience.11 Francesco Asti, within his experiential-phenomenological method,12 has shown that “mystical life is not dissimilar from living according to the Spirit, when the believer is open to the Trinitarian mystery that involves all of his faculties in his life context,”13 and notably in this, the mystical life “is not a single experience,” but rather ←4 | 5→is “a harmonious set of all the colors that meet in Christ.”14 The affective dimension, which is a collaboration of the believer with the Spirit, also “enters into the vitality of the encounter between God and his creature,”15 and this walk with God, which is spurred on by the Spirit, will be authentic “when the believer expresses her affective knowledge of Christ from the concreteness of her existence.”16 Also within a general phenomenological method,17 and utilizing the privileged laboratory of the saints,18 Domenico Sorrentino has proposed four interactive “polarities” in their fundamental dynamics (and with their various anthropological registers)19 for an orderly understanding of the experience of God: (1) the primary history-eschaton, as human history moves towards its finality in eternity; (2) the unitive dynamic with God, as expressed in the union between God-Trinity and the human person; (3) the action of divine grace, the dynamic of grace with human nature; and (4) the ongoing interaction of the word of God and the Holy Spirit in its dynamic with the Church.20 For us, Julian of Norwich is our privileged spiritual laboratory regarding all of the above dynamics of the Spirit of God in relationship with our humanity.

Jesús Manuel García Gutiérrez has summarized the three steps for our methodology in the spiritual theology of humankind’s quest to find God: (1) the historical-phenomenological; (2) the hermeneutical-theological; and (3) the mystagogical.21 The historical-phenomenological method describes the phenomenon “in the concreteness of the existence of the subject [the experiencer].”22 Regarding this methodology, García Gutiérrez also makes ←5 | 6→a number of very specific observations: (a) the experience is realized “not as a product of consciousness, but as something that is given to us within two asymmetric realities”: in the “ineffable mystery of God” and with “the assent and obedience of the man who suffers passivity in the presence of the mystery”;23 (b) the experience “does not exist within a timeless perspective,” but “always it arises in an historical event, embedded in its specific and personal experience”;24 (c) the particular experience “has its own history – the story of a spiritual life”;25 and (d) the experience implies a certain “passivity” on the part of the subject, because the experience “arises from irruption of the divine transcendent mystery in the life of the subject.”26

For the interpretation of spiritual texts, “empathy”, in its general character, presents two dimensions running through our method: (1) how our true understanding of another person’s (or subject’s) experiencing requires of us our “empathy,” which is rooted in our discernment of their feelings and in their conscious experience of the “foreign” other; and (2) how those descriptions by others of their “religious experiences,” or of their “experience” of God, is grounded in God’s “empathy” with that experiencer, which “meaning” also is given as interpersonal (relational) and intersubjective (interiorized). In that experience, as given from God, empathy towards the experiencer (the gifted) is manifested (in its givenness) by the divine; and the divine character of this manifestation is recognized by the experiencer empathically, just as that empathy (in its particular affective equivalence by form) must be experienced in some (either limited or maximal) degree by the interpreter (also with God’s grace) for any valid interpretation of a spiritual text.27 As Edith Stein has noted, “Empathy as the basis ←6 | 7→of intersubjective experience becomes the condition of possible knowledge of the existing outer world.”28 Empathy, also, determines how it is that we may come, by an excess of intuition,29 to acquire possible knowledge of a transcendent God who is “wholly other”.30 “Religious experience” reveals ←7 | 8→its essence and its truth precisely on this affective level (but not as intersubjectivity, nor interobjectivity), but as intergivenness:31 as the “gifted” is gifted in her entirety by “the other” (or by the not actually “wholly other”);32 for the one “gifted” (by God, as also is allowed for by the theoretical “gap” between the giver and the gift in Marion’s hypothesis of “givenness”33) is ←8 | 9→“he who receives and receives himself [totally]34 from the given,”35 as all we have and all we will become is antecedent in God.

This affective dimension in mystical experience is evident for the reading of spiritual texts and, by analogy to it, is similar also to the erotic discourse in ordinary life. William of St. Thierry, in his Sermons on the Song of Songs, had described the “turnabout from the text to the non-text [my emphasis] of divine Self-communication,”36 by his antimonial distinction “word/voice”: although the “word” in text has its linguistic form (their letters and syllables), the “voice” from God forms no part of any linguistic system of referents: so that, for William of St. Thierry, the divine “Voice” is “purely affection” and “where it works it works only as it is;”37 and there, it also is “face.”38 But Jean-Luc Marion sees a linguistic similitude for the “third path” of eminence (Denys): apart from its unnecessary (and absent) linguistic forms (as in the erotic discourse for lovers), there is a pragmatic “temporalizing language strategy” that “keeps alive a dialogic situation.”39 Here Marion’s descriptions, as Christina Gschwandtner has ←9 | 10→observed, seem to pertain more to the activity of mystical “prayer” (which is a correlative activity, in affect, for the reading of spiritual texts) than to the “phenomena of revelation.”40

While Scripture is privileged spiritual text,41 all authentic Christian spiritual texts are also derived from – and proceed from – the Word of God,42 as Edith Stein has reminded us of the Word’s (Logos) obligatory ←10 | 11→force and power, of the very meaning and power of the Spirit of God.43 The “Word of Life” engenders the one to whom it is addressed, as Michel Henry has written, “by making him a living.”44 So, in fact, Julian of Norwich’s texts are Julian’s “Gospel,”45 as Christ is made manifest and explicit for us within her process of lectio divina,46 who then appears as Logos, and also in her lectio divina throughout her text with Julian’s implicit references to Scripture.47 Julian has written her texts sourced in her own “reading” (from ←11 | 12→the lectio) of her original revelation experience. And in doing so, Julian has also engaged all four of the processes that Guigo II had defined for lectio divina: reading (lectio);48 meditation (meditatio);49 prayer (oratio);50 and contemplation (contemplatio).51 In preparation for lectio divina, in Julian’s preparation for her writing and her revelations, and in ours for the process of one’s reading and praying of spiritual texts, there is first an initial attitude of attention and silence;52 and with it a psychological posture of ←12 | 13→“right” disposition and “fitting” expectations.53 The distracted and the proud, except by God’s mercy, are not usually privileged by grace above the worshipful and the humble.54 Generally, the necessary virtue for divine contemplation, as Meister Eckhart has indicated, is “pure detachment,”55 because although humility can exist alone, pure detachment cannot exist without humility.

In lectio, one seeks: but the process of divine movement only begins with the reading, from the literal sense (soma) of the text. The initial “performance” of the text is an “external exercise,” literally “somatic” in its immediate effect on the bodily senses (seeing, hearing, touching, smelling, tasting), as the tangible and obvious meanings of the text “light up” the “exterior” and physical world without. In meditatio, one finds: the reflective attention of the reader is directed towards the “interior of the text,” where text fragments are studied by the intellect from all directions, which beckons the reader to itself from itself. This process of meditation then orients “passion,” from whence emerges the oratio in its God-relatedness; here one asks: in prayer and inquiry, towards the will of God as there is God’s grace. The meditation ignites and feeds the prayer, while reciprocally prayer also ignites and feeds the meditation. In contemplatio, one feels: “God now has a voice and a face,” potentially within thought (the power of words to describe and comprehend) but now more fundamentally felt (beyond words), where the ultimate sense (theoria) of the spiritual text may be realized in ←13 | 14→its reading. During the temporality of contemplation, the totality of one’s being engages with the spiritual (nous) in its otherness and its sameness; by God’s gift, the mystical secret is received and contemplated; and of itself human understanding must simply fail, which only the divine can up raise by grace to gift. In the final praxis of faith and grace (whether in darkness or in light), the proficient now lives, acts, and prays in God’s life from the depths of God’s love.

The primary reason Julian’s early fifteenth-century text (Long Text, c.1413–1416) has survived for 600 years, the reason there is any text at all, is that it is a spiritual text. One can engage with Julian of Norwich as a literary text; and there are countless academic perspectives for doing so. Diverse academic perspectives (within philosophy, theology, language studies, and history) may offer a context for Julian’s underlying religious experience, but what did Julian intend? What was her meaning? As a spiritual text, the author intended a dialogue with the reader for the reader’s spiritual benefit; but as a spiritual text, the text is not simply its author’s. The author labours; but the work is sourced in God’s spirit. In Julian’s case, the work originates in her prayer; the prayer originates in God; the intention of God eventuates in this revelation of love; God’s mercy and grace build upon Julian’s weaknesses and abilities; Julian allows herself to be transformed; that process is a long one, it never ends in this life; Julian is drawn into God in her soul; she prays and contemplates, and is drawn deeper into love, as she is given the grace. While the grace is unique to her, as is particular for all, she is led by faith in God’s love for her to embrace all souls in the body of Christ with the love that Christ increases in her. In the spiritual text, we also are drawn up into God by his grace. But without a spiritual perspective, or without reading Julian as a spiritual text, God’s purpose in Julian would remain without his spirit in us; and it would be unintelligible, or without effect.

The purpose of this book is to engage with Julian’s text as a spiritual text and to explore its context and meaning in Julian’s intention. Julian sets out (hers is the original experience and unique grace) to partially unfold (by word and spirit by grace) a careful and precise narrative (an integrated whole) structured by the chronology and phenomenology of her experience; but it is also a product of long prayer, contemplation, and grace; which has its natural time, within Julian’s limitations and with the augmentations of grace – both are the ←14 | 15→same, God’s natural and spiritual gifts. There is Julian’s historical context, but it is largely absent from her text; there is her personal context, but the historical persona is withdrawn from our sight in humility, although her soul is revealed to us in truth; so Julian universalizes God’s gift to us in her unique grace. And with her “courtesy” and “reverent dread,” she unfolds, in the determination of her faith, what the Lord himself shows to her; step by step, how he teaches her; and how Our Lord teaches us now. Julian walks courageously in confidence by faith, sustained by the love that God shows her in the Cross and the grace he continues to measure out to her. It is God who knows her, sees her, and keeps her, even in his literal absence (when she doesn’t see or feel him), when the darkness she experiences (the illness and the woe) also was God’s gift. But in prayer, God is always found dwelling in her soul, where he is the “ground” of her and of our “besekyng.” How to walk in the light of God’s mercy and grace, the light of faith, and the light of charity through the darkness of natural life, is Julian’s contemporary gift to us, as we are blessed in God’s mercy and grace by life, love, and light, by reason, charity, and faith.56

←15 | 16→The logic of our twenty-first-century secular culture would define all religious belief and experience, such as Julian of Norwich’s “revelations” in particular, as no more than “a logical category of judgment,” as a “conceptual truth,” without objective (or “empirical”) basis in “factual information,” except for the preferred “objectivity” of scepticism.57 The “truth” of Julian of Norwich would simply be her personal interpretation. Accordingly, such “gifted” persons would “use their own sense of themselves as a guide in trying ←16 | 17→to understand divine revelations,”58 and their “spiritual power” would derive from a “new principle of judgment,” in a “fuller sense of life’s meaning.”59 In this view, Julian of Norwich simply had turned her “vision experiences” into “a revealed teaching” in order to change the interpretation of “traditional verbal revelations.”60 And accordingly, if Julian had interpreted her “revelation” experience in a non-Christian manner, they would not have been accepted, except because Julian’s interpretations are “enshrined in Christianity’s tradition.”61 This secular view,62 ensconced in the postmodern culture of Logical ←17 | 18→Positivism,63 denies the entire spiritual reality of Julian’s experience in the dialectic of her prayer.64 In the modern neglect of God, humanity (in its self-idolatry) not only denies its own existence and its destiny in God, but it would deny its very life. Julian of Norwich, on the contrary, upholds the dignity of human nature in God’s eternal plan.65 Now, today, from Julian’s “distance” of more than 600 years ago, we can see and learn (as we may come to understand) how God is found (in the actual beholding, contemplation) through our genuine prayer and in our active searching.66

1 Julian of Norwich presents her short summary of this theology of sin and salvation, in relationship to nature and grace (cf. Barry Windeatt, ed., Julian of Norwich: Revelations of Divine Love (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), p. 131) in her Long Text [LT 63/1–13], and continuing until that chapter’s conclusion [LT 63/38–39]: “Thus I understode that al his blissid children which ben comen out of him be [by] kinde [nature] shal be browte ageyn into him be [by] grace.”

2 As examined by David Aers (cf. David Aers, “Sin, Reconciliation, and Redemption: Augustine and Julian of Norwich,” Salvation and Sin: Augustine, Langland, and Fourteenth-Century Theology (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 2009), pp. 133–171) this also contrasts with a central paradox of Julian’s theology (p. 170): “Julian systematically ignores our freedom to disobey the covenant offered by the source of life, to destroy others and ourselves, individually and collectively, as we strive to shore up the power of the earthly city we inhabit … Julian’s theology does not, probably cannot, address collective life and its domination by will and power alienated from God and the covenants.”

3 Jean-Luc Marion points the way by two certainties of method (cf. Jean-Luc Marion, Givenness & Revelation, translated by Stephen E. Lewis (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), p. 60): “the Spirit of truth” and “charity”: “The Holy Spirit sets the method of interpretation for the saturation of the phenomenon of Revelation. A second certainty follows: we must always consider that that which reveals itself in the saturated phenomenon of Revelation involves, as its alpha and omega, a single and unique excess: that of charity.”

4 Emmanuel Levinas, Totality and Infinity: An Essay on Exteriority, 4th edition (Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1979/1991), pp. 187–253, “Section III: Exteriority and the Face”; for there also is an ethical dimension to the experience that calls forth action: “to meet the other, to see this person’s face, is to hear a voice summoning me” (as Max Van Manen has summarized Levinas, in Phenomenology of Practice (London: Routledge, 2014/2016), p. 116.

5 The Holy Bible: The New Revised Standard Version, Second Catholic Edition (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2006).

6 Christina M. Gschwandtner, Degrees of Givenness: On Saturation in Jean-Luc Marion (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2014). Gschwandtner notes (p. 7): “Saturated phenomena are identified precisely through the effect they have on the person who witnesses them.”

7 Marion has distinguished between “revelation” (as possible phenomenon) and “Revelation” (as actuality of God by himself), delimiting philosophy and theology as separate regions of science (Jean-Luc Marion, Being Given: Toward a Phenomenology of Givenness, translated by Jeffrey L. Kosky (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2002), p. 367 (endnote 90)). Marion’s theology regarding “Revelation” is necessarily Trinitarian (Jean-Luc Marion, “A Logic of Manifestation: The Trinity,” in Jean-Luc Marion, Givenness & Revelation, 2016, p. 99).

8 See §24, To Give Itself, to Reveal Itself: The Last Possibility – the Phenomenon of Revelation, in Jean-Luc Marion, [“Etant donné: Essai d’une phénoménologie de la donation”] Being Given: Toward a Phenomenology of Givenness, translated by Jeffrey L. Kosky (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2002), pp. 234–247.

9 Cf. Jean-Luc Marion, The Visible and the Revealed, edited by John D. Caputo, translated by Christina M. Gschwandtner (New York: Fordham University Press, 2008), p. 152: “For ‘grace [charité] and truth came through Christ Jesus’ (John 1:17), and we have seen him, see him, and will see him, at once and indissociably, ‘saturated with love and with truth’ (John 1:14; trans. modified).”

10 Ciro García, “Il metodo fenemenologico della Teologia spirituale,” Mysterion 6, No. 2 (2013): 172–186, p. 178.

11 Charles André Bernard (1913–2001) has originated a theological and phenomenological framework for a scientific discipline of Christian spirituality [cf. Charles André Bernard, “La teología spiritual como disciplina científica,” in Teología Espiritual: Hacia la plenitude de la vida en el Espíritu [Teologia spirituale, 6th edition, 2002], 87–120, translated by Alfonso Ortiz and Vincente Hernández (Salamanca: Ediciones Sígueme, 2007), whose more developed presentation and crowning achievement was his Teología Mística, published after his death in Rome on 1 February 2001 (cf. Charles André Bernard, Teología Mística [Théologie Mystique, 2005], edited by Maria Giovanna Muzj (Burgos: Monte Carmelo, 2006)). In his Teología Mística (pp. 18–47), and clearly applicable to Julian of Norwich’s rationale for her spiritual texts, Charles André Bernard has described: (1) the general principles of spirituality, including the communication of the divine life and the life of grace; (2) the experiential subject of the spiritual life, including the sensible activity of the Spirit and its relation to affective life; (3) the realization of the interpersonal dialogue between God and humankind, including the human response in charity to the transcendence of God by action and prayer; and necessarily, (4) the progressive life in the Spirit, in terms of its development and its mystical dimension. Likewise, Bernard Lonergan’s phenomenological and epigenetic theological method in its dialectic (cf. Bernard Lonergan, Method in Theology, 2nd edition, reprinted (Toronto: University of Toronto Press for Lonergan Research Institute, 1973/2013), pp. 235–266; Jean Piaget’s L’épistémologie génétique, 1950) is consistent with Jean Piaget’s epistemological critique of Edmund Husserl where both had criticized Husserl’s “highly purified empiricism,” based upon the necessary and interactive relationship between “insight” and “activity” (cf. Jean Piaget, Insights and Illusions of Philosophy [Sagesse et illusions de la philosophie, 1965], translated by Wolfe Mays (New York: World Publishing Company, 1971), p. 104; Bernard Lonergan, Collected Works of Bernard Lonergan, Vol. 3, Insight: A Study of Human Understanding, 5th edition revised and augmented, and reprinted, edited by Frederick E. Crowe and Robert M. Doran (Toronto: University of Toronto Press for Lonergan Research Institute, 1957/1992/2013), p. 440).

12 Francesco Asti, Teologia della Vita Mistica: Fondamenti, Dinamiche, Mezzi (Vatican City: Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2009).

13 Francesco Asti, “Teologia spirituale ed esperienza spirituale Cristiana,” Mysterion 5, No. 2 (2012): 76–102, p. 93.

14 Ibid.

15 Ibid., p. 101.

16 Ibid.

17 Domenico Sorrentino, L’esperienzia di Dio: Disegno di teologia spirituale (Assisi: Cittadella, 2007).

18 Ibid., pp. 62–63.

19 Ibid., p. 130.

20 Ibid., pp. 117–118, 138.

21 Jesús Manuel García, “Lo statuto epistemologico della Teologia spirituale in contesto interdisciplinare,” Mysterion 5, No. 2 (2012): 48–75, pp. 62–67; Jesús Manuel García Gutiérrez, “Il metodo ‘teologico esperienziale’ della teologia spirituale,” Mysterion 9, No. 1 (2016): 5–17.

22 Jesús Manuel García, “Lo statuto epistemologico,” p. 62.

23 Jesús Manuel García Gutiérrez, “Il metodo ‘teologico esperienziale,’” p. 6.

24 Ibid., p. 7.

25 Ibid., p. 8.

26 Ibid.

27 Cf. Jean-Luc Marion, Givenness & Revelation (p. 64): “In order to see the uncovered mystērion, it is thus necessary to pass from our spirit to the Spirit of God, so as to see it as God sees it [my emphasis]. This is nothing less than an overturning of intentionality: taking the intentional gaze of God on God, instead of claiming to retain our intentionality in front of the intuition of the mystērion.” Marion has said the same for the hermeneutics of biblical text [Jean-Luc Marion, God without Being: Hors-Texte, 2nd edition [Dieu sans l’être: Hors-texte, 1982], translated by Thomas A. Carolson (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1991/2012), p. 149: “The text results, in our words that consign it, from the primordial event of the Word among us; the simple comprehension of the text … requires infinitely more than its reading … it requires access to the Word through the text [which is a divine revelation, not revealed by humankind, but by the Spirit of God]. To read the text from the point of view of its writing: from the point of view of the Word [my emphasis].”

28 Cf. Edith Stein, On the Problem of Empathy, Collected Works, Vol. 3, translated by Waltraut Stein (Washington, DC: ICS Publications, 1989), p. 64. Also see: Edmund Husserl, Ideas Pertaining to a Pure Phenomenology and to a Phenomenological Philosophy: First Book, translated by F. Kersten (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1913/1983), p. 363: “The intersubjective world is the correlate of intersubjective experience, i.e., <experience> mediated by ‘empathy’ … above all, however, we are referred to the novel factor of empathy and to the question of how it plays a constitutive role in ‘Objective’ experience and bestows unity on those separated multiplicities.”

29 Jean-Luc Marion, In Excess: Studies of Saturated Phenomena [De Surcroît: Études sur les phénomènes saturés, 2001], translated by Robyn Horner and Vincent Berraud (New York: Fordham University Press, 2002), p. 159: “The intention (concept or the signification) can never reach adequation with the intuition (fulfillment), not because the latter is lacking but because it exceeds what the concept can receive, expose, and comprehend”; and (pp. 161–162): “First, the excess of intuition is accomplished in the form of stupor, or even of the terror that the incomprehensibility resulting from excess imposes on us […] Access to the divine phenomenality is not forbidden to us; in contrast, it is precisely when we become entirely open to it that we find ourselves forbidden from it – frozen, submerged, we are by ourselves forbidden from advancing and likewise from resting. In the interdiction, terror attests the insistent and unbearable excess of the intuition of God. Next, it could also be that the excess of intuition is marked – strangely enough – by our obsession with evoking, discussing, and even denying that of which we all admit to having no concept.”

30 Rudolph Otto, The Idea of the Holy: An Inquiry into the Non-Rational Factor in the Idea of the Divine and Its Relation to the Rational, translated by John W. Harvey, revised with additions (London: Oxford University Press, 1923/1936), pp. 25–30. Jean-Luc Marion’s phenomenological and theological framework of “givenness” provides a contemporary solution for Otto’s classic problem in the context of the three paths offered in “mystical theology” (Denys “the Areopagite”), those corresponding to the affirmative (kataphasis), negative (apophasis), and hyperbolic (eminence). For the latter way, of via eminentiae, in an analogy to the pragmatics and perlocutions of erotic discourse, Marion states (cf. Jean-Luc Marion, “What Cannot Be Said,” in The Visible and the Revealed, 101–118 (New York: Fordham University Press, 2008), p. 116): “It is no longer a question of a discourse about beings and objects, about the world and its state of affairs, but rather the speech shared by those who discourse about these things when they no longer discourse about them but speak to one another.” It is a matter of “de-nomination” (cf. Jean-Luc Marion, “In the Name: How to Avoid Speaking of It,” in In Excess: Studies of Saturated Phenomena [De Surcroît: Études sur les phénomènes saturés, 2001), 128–162 (New York: Fordham University Press, 2002), pp. 134–142) within its description as saturated phenomena (ibid., p. 160): “Excess [of intuition] conquers comprehension and what language can say […] in short, God remains incomprehensible, not imperceptible – without adequate concept, not without giving intuition.” Accordingly (ibid, p. 162), “The Name – it has to be dwelt in without saying it, but by letting it say, name, and call us. The Name is not said by us; it is the Name that calls us. And nothing terrifies us more than this call … because we hold it to be a fearful task to name with our proper names the One … to whom God has bestowed the gift of the name above all names.”

31 Jean-Luc Marion, Being Given: Toward a Phenomenology of Givenness (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2002), p. 323.

32 Cf. Jean-Luc Marion, Givenness & Revelation, 2016, pp. 104–106. God is not subject to finite knowledge, or to the idolatry of any attempted reduction, because God is not an object and God cannot be reduced to a concept. However, Otto’s alleged “wholly other” of the divine is not completely so: for knowledge of God is possible: (1) from the Father (the invisible of the Son), by virtue of the soul’s spiritual life, which is gifted and shared from the divine spirit; (2) from the Son (the visible of the Father), by virtue of the material incarnation, death, and resurrection of Christ, the God-Man; and (3) from the Holy Spirit (The icon shows the Son as the Father only if God gives the grace, the art, and the manner of seeing it as it should be seen; and God gives it as the Holy Spirit, as the one who remains invisible in the icon because he shows it), by grace.

33 Jean-Luc Marion, God without Being, Hors-Texte, 2nd edition, translated by Thomas A. Carlson (Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press, 1991/2012), p. 104: “Distance lays out the intimate gap between the giver and the gift, so that the self-withdrawal of the giver in the gift may be read on the gift, in the very fact that it refers back absolutely to the giver.”

34 God as the “absolute given” always gives himself entirely. Yet, what gives itself of God is yet to be fully realized within the soul’s material limitations of existence. We encounter here the mystery of “incarnation” for human salvation (cf. Michel Henry, Incarnation: A Philosophy of Flesh, translated by Karl Hefty (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 2000/2015, p. 260): “Because ‘God engenders himself as myself,’ and because ‘God engenders me as himself,’ then, truly, because it is his life that has become my own, my life is nothing other than his own: I am deified, according to the Christian concept of salvation.”

35 Jean-Luc Marion, Being Given, translated by Jeffrey L. Kosky (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2002), p. 323.

36 Kees Waaijman, Spirituality: Forms, Foundations, Methods, translated by John Vriend (Leuven: Peters, 2002), p. 707.

37 Kees Waaijman, Spirituality, 2002: p. 707: from Guillaume de Saint-Thierry, Exposé sur le Cantique des cantiques, par Jean-Marie Déchanet (collection « Sources Chrétiennes », n° 82) (Paris, 1998), p. 141.

38 Kees Waaijman, Spirituality, 2002, pp. 707 & 727; and Guillaume de Saint-Thierry, ibid, pp. 147 & 149.

39 Jean-Luc Marion, In Excess, 2002, pp. 115–116: “We tell each other nothing in a certain (constative) sense, yet by speaking this nothing, or rather, these nothings, we place ourselves (pragmatically) face to face, each receptive to the (perlocutionary) effect of the other, in the distance that both separates and unites us. Constative and predictive (locutionary) or even active (illocutionary) speech definitely gives ways to a radical pragmatic (perlocutionary) use: neither saying nor denying anything about anything, but acting on the other and allowing the other to act on me.”

40 Christina M. Gschwandtner, Degrees of Givenness: On Saturation in Jean-Luc Marion (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2014, p. 146: “Somewhat surprisingly, the final chapter of In Excess, which really should examine the possibility of a phenomenon of revelation if it consistently followed the outline of the five kinds of saturated phenomena (event, idol, flesh, icon, revelation) as presented in Being Given and the first chapter of In Excess, instead examines the kind of language appropriate for the divine. This language turns out to be prayer or praise. In some sense, then, this simply continues the earlier distinction between an idolatrous and an iconic way to approach the divine. Yet, formulated as a response to Derrida on negative theology, it is a much more conscious articulation of the linguistic element in prayer.”

41 As Pope Benedict XVI notes in his encyclical Verbum Domini (30 September 2010, 17): “Although the word of God precedes and exceeds sacred Scripture, nonetheless Scripture, as inspired by God, contains the divine word (cf. 2 Tim 3:16) “in an altogether singular way.” Scripture cannot be understood [interpreted] as text alone, apart from the magisterium and the living community of believers, apart from the living faith, which originates in God; so its hermeneutics is part of the ongoing temporal and living tradition of the church, which is both historical and communal; beyond simply words, scripture is living and divine [Logos]: namely (cf. Jean-Luc Marion, God without Being, p. 149): “The theologian must go beyond the text to the Word, interpreting it from the point of view of the Word.” Ultimately, both hermeneutics and revelation are linked by the decision of faith, by the gift to believe in Christ, where believing is seeing (cf. Jean-Luc Marion, Givenness & Revelation, pp. 41–42): “We believe in God when we will it, clearly; but we will it only when we love that which we desire; and in the case of God, we receive this desire (desire for pleasure) from God alone … for without the hermeneutic decision, there is nothing to see, nothing to believe, and nothing revealed.”

42 Julian of Norwich, ST 6/42–43 (cf. Barry Windeatt, Ed., Revelations of Divine Love, 2016, p. 7): “Thane schalle ye sone forgette me that am a wrecche, and dose so that I lette yowe nought, and behalde Jhesu that ys techare of alle.” There is only one Teacher, the Word. Implicitly, “But you are not to be called rabbi, for you have one teacher, and you are all brethren” (Mt 23:8); and also, in Julian’s social obligation for writing her texts, “You call me Teacher and Lord; and you are right, for so I am. If I then, your Lord and Teacher, have washed your feet, you also ought to wash one another’s feet” (Jn 13:13-14).

Details

- Pages

- VIII, 592

- Publication Year

- 2023

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781800799158

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781800799165

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781800799141

- DOI

- 10.3726/b19869

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2023 (June)

- Keywords

- Human-Divine collaborations Julian of Norwich phenomenological textual analysis history of Christian religion and spirituality Julian’s primordial religious experience Historical manifestation of Julian’s graced experience

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, New York, Wien, 2023. VIII, 592 pp., 1 fig. b/w.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG