Eros and the Pearl

The Yezidi Cosmogonic Myth at the Crossroads of Mystical Traditions

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Prologue and acknowledgements

- List of abbreviations

- Note on transliteration, names, punctuation, quotations and dates

- 1. Introduction. Research problems and methodology

- 1.1. Problems with Yezidism

- 1.2. Problems with comparatism

- 1.3. The method

- 2. The Yezidis and their religion

- 3. Sources for research on the Yezidi cosmogony

- 3.1. Oral tradition and taboo on literature

- 3.2. Qewls, the Yezidi sacred hymns

- 3.3. The language of the Qewls and difficulties with its understanding

- 4. Yezidi cosmogony in oral tradition and ritual

- 4.1. Reconstruction of the Yezidi cosmogony

- 4.2. The Yezidi holy day, Wednesday, and its cosmogonic meaning

- 4.2.1. Wednesday in the Yezidi tradition and Hermes-Mercury

- 4.2.2. Cosmogonic myth and the festival of the Wednesday

- 4.2.3. The Yezidi musical instruments and cosmogony

- 5. The motif of the Pearl in the Yezidi cosmogony and its parallels in other traditions

- 5.1. The Pearl in the Yezidi cosmogony

- 5.2. The Pearl and berat

- 5.3. The Pearl theme in other traditions

- 5.3.1. The Christian pearl and the Parable of the Merchant

- 5.3.2. The Hymn of the Pearl

- 5.3.3. The Manichaean pearl

- 5.3.4. The Mandaean pearl

- 5.3.5. The Pearl in the Yaresan tradition

- 5.3.6. The Zoroastrian Sky

- 5.3.7. Islam and the pearl of the Sufis

- 5.3.8. The One of the Greeks

- 5.3.9. The Orphic Egg and some other eggs

- 6. The Yezidi motif of cosmogonic Love and its analogies in other traditions

- 6.1. Two aspects of mystical Love in Yezidism

- 6.1.1. Cosmogonic Love

- 6.2. The branch of Love and Sheikh Sin

- 6.3. Cosmogonic Love in other traditions

- 6.3.1. God’s Love in Yaresan and Mandaean traditions

- 6.3.2. Love and the mystical branch of Islam

- 6.3.2.1. Sufism and Yezidism

- 6.3.2.2. Muslim mysticism and the Greeks

- 6.3.2.3. Love as a way to unity with the One

- 6.3.2.4. Love, Quran and heresy

- 6.3.2.5. Two names of love – ‘ishq and mahabba – and God’s Love for Himself

- 6.3.2.6. The Love loving Love – Hallaj and the Greek fire

- 6.3.2.7. Plant metaphors of love in Sufism and the Yezidi ‘branch of Love’

- 6.3.2.8. Fallen lover, fire and Adam

- 6.3.2.8.1. Iblis, Azazil and Tawusi Melek

- 6.3.2.8.2. Iblis and love to God

- 6.3.3. Cosmogonic Love in Ancient Greek sources and the Orphic Eros

- 6.3.3.1. Eros of poets and Love of philosophers

- 6.3.3.2. Firstborn Love in the Orphic tradition

- 6.3.4. God and Love at the beginning of the Christian tradition

- 6.3.5. The divine name of Eros: the neo-Platonic Christian tradition

- 6.3.6. Love, Logos and the Alexandrian melting pot

- 6.3.7. Eros and the religious syncretism of Late Antiquity: Platonists and Gnostics

- 6.3.8. Love, Logos and the winged serpent

- 6.3.9. Eros and the Serpent from the bowl

- 7. Parallels to the motif of Eros and Pearl in the oldest cosmogonies

- 7.1. Egg, Love and Hermes. Phoenician cosmogony

- 7.2. Prajapati, Love and the Golden Egg in Hindu tradition

- 7.2.1. Hindu elements in the Yezidi tradition and the sanjak

- 8. Crossroads of traditions – from Harran to Lalish

- 8.1. Orphic traces in Northern Mesopotamia

- 8.2. Greek traces in Northern Mesopotamia

- 8.3. Harranian ‘Sabians’ at the crossroads of traditions

- 8.4. Harranians and the Yezidis

- 8.5. The Sun-worshippers in Kurdistan

- 8.6. The Shamsis and the Shamsanis

- 9. Epilogue

- 10. Appendix: Kurmanji text of Qewlê Zebûnî Meksûr

- 11. Bibliography

- 12. Index

Prologue and acknowledgements

The reason for writing this book was the desire to understand the old myth of Love hidden in the primordial Pearl. Using the language of metaphor, I must say that I have fallen under the charm of a pearl glow, which emanated from the bottom of the sea and which made me put aside everything else and dive into the depths, descending lower and lower, chapter after chapter, to find it and bring it to daylight. Thus, it is also a report on the search for hidden treasure dedicated primarily to other pearl divers. In retrospect, I can see that I had been preparing to write it for about twenty years, which consisted first of study on Greek philosophy, especially Platonism and Greek cosmogonies and their reception in Late Antiquity, then on Sufism and Yezidism.

I would like to make special mention here of an incident that took place in the course of my preliminary work on this book, when I learned that the Yezidis of Georgia opened the first Yezidi ‘temple’ outside Iraq called Quba Siltan Êzîd, i.e. ‘the Dome[-shaped building] of Sultan Yezid’. I decided to visit it as soon as possible and, at the same time, to get an idea of the specifics of the diaspora, with which I had no opportunity to get acquainted before. Until then, I only knew the Yezidi people of Iraq and I had visited their sacred sites there. In August 2015, I travelled to Tbilisi, and when I finally managed to find and see the building crowned with a radial dome, characteristic of the Yezidi architecture, I noticed a young moustached man dressed in a traditional Yezidi costume, with a turban on his head, who walked barefoot through the courtyard. I felt like I was in Lalish, yet the post-Soviet blocks and the noise of cars in front of the gate did not allow this vision to materialise properly. The young man turned out to be a pir and a leader of the Georgian Yezidis whose vast religious knowledge I had previously heard about from Yezidis in Iraq and Turkey. Many of them, including the highest spiritual leaders, knew him very well from the time he served in the Lalish sanctuary as a volunteer acolyte (xilmetkar).

I introduced myself by saying that I was writing a book about the Yezidi cosmogony and, if he agreed, I would gladly ask him some questions about it. Dimitri Pirbari accepted my request and, as the sun was shining very strongly, we sat down in the arcades of the shrine and started to talk. With every word that followed, I felt that I had encountered the ‘right man’, who not only possessed a deep knowledge, but was also interested in similar issues as me. This is how a friendship was born, which I could always count on during my research on Yezidism.

In the course of the conversation, Pir Dima, as it is the form he uses among the Yezidis, admitted that he is also in the process of writing a book. I asked about the subject and the title, and to my amazement he replied: – Тайна жемчужины, that is The Mystery of the Pearl. Pir Dima’s book, which contains the description of the principles of Yezidism, its history and the translation of the Yezidi religious hymns, ←13 | 14→which were rendered into Russian by Dmitri Shchedrovitskiy, was published in Russian in 2016, and a year later in the Georgian language.

In the meantime, I continued my work, which was greatly helped by receiving the Fuga 5 Internship from the National Science Centre of Poland, within the framework of which I was able to carry out a research project at the Department of Iranian Studies of the Jagiellonian University entitled Eros and the Pearl in the Yezidi Cosmogony (2016/20/S/HS1/00055), which the present publication is the result of. Throughout this post-doc research, I was always able to count on the help and favour of the academics associated with the university, especially an Iranist, Anna Krasnowolska, and a Kurdologist, Joanna Bocheńska, for which I would like to thank them at this point.

The Reader might rightly ask: What was the reason for choosing this particular topic? The need to write this book arose from a question that emerged during my research on the philosophy of the ancient Greeks, especially Plato’s cosmology, to which I have devoted many years of studies and a doctoral dissertation at the Faculty of Philosophy of the University of Warsaw, and which I have continued to conduct in parallel with my research on the religion of the Yezidis. Analysing the scant information on the cosmogony of the Yezidis, I noticed some convergence between Platonism and Yezidism – both in the area of cosmology and in the theocratic organisation of the political community. My special interest was also aroused by the theme of Love in the Yezidi cosmogony and its relationship with the primordial Pearl that was extolled in the Yezidi hymns. At a first glance, the thread seemed quite original, but I saw its distinct parallels in the ancient Greek cosmogonies, especially the one spread by the Platonists and attributed to the Orphics. Thus, my question was: Could the Yezidis have assumed the Greek cosmogonic motif? Do we witness a cultural trace of contact or does it belong to their original religious thought? This has raised further doubt: Perhaps they both share a motif that was not invented by them at all, but was taken by the Yezidis, either from Sufism or perhaps from another, earlier source? This, in turn, raised more questions: If we were witnessing a borrowing, how was it possible for it to take place? Should we accept a chance that a mere coincidence occurred here, without any connections in the form of transmission of the cosmogonic motif? After all, the wheel may have been invented independently by various people working separately, and the mere fact of using it does not entail that they acquired it from others.

If answers to these questions were to be provided in any way, it was necessary, first, to juxtapose these similarities and, second, to attempt to answer one more complex question without which it would be difficult to draw any serious conclusions: Who are the Yezidis, where do they come from and how far back in time does their tradition go? In a sense, the subject of this book became a pretext for extensive research and reflection on Yezidism itself and its origins. In this respect, the book offered to the Reader challenges the paradigms hitherto prevailing in the Yezidi studies and opens the field to new discussions. In presenting new findings and hypotheses, which at first glance may look controversial, I have done my best to justify them both through the source material and the argumentation.

←14 | 15→Dealing with all these issues necessitated the development of a specific method, which would combine the sets of tools a historian of philosophy, philosopher, and cultural anthropologist have at their disposal. While, as regards the Greeks, for example, there exist critical editions of ancient texts and countless comments on them that have been made over the course of tens of centuries, in the case of the Yezidis, we constantly encounter question marks that result from the paucity of sources. The studies on Yezidism are a much younger discipline than the history of ancient philosophy and classical philology. It was not until the 1970s that the academic world learned for the first time about the content of the holy Yezidi hymns (qewls), which are the most important source for Yezidologists. Nor is the research into the study of Yezidism facilitated by the fact that it still remains a very hermetic religion. For a variety of reasons, even the Yezidis themselves do not know the answers to many questions about their tradition either.

In short, to compare the Yezidi legends about the beginning of the world with cosmogonies that appeared in the region inhabited for centuries by the Yezidis, it was necessary to establish the precise outline of the Yezidi cosmogony. This, in contrast to research within the scope of the history of philosophy and classical philology, required not only becoming acquainted with the Yezidi cosmogonic hymns, but also involved field research. This included conversations with the Yezidis themselves and searching for cosmogonic threads also in other sources, especially in their festivals, which I have had the opportunity to become a witness of in Iraq, Georgia and Turkey. Particularly important was the New Year’s Serê Sal festival, celebrated in the most holy Yezidi place, Lalish, which I visited for this occasion in April 2014, 2015, and 2018. I visited Iraq many times in other years as well. I could always count on the hospitality of the Yezidis and valuable conversations, which allowed me to understand better the specifics of their religion. I had already been prepared for this kind of research, because apart from studying Philosophy, Classical and Oriental Studies, more than twenty years ago I learnt how to carry an ethnographic research and undertook my own fieldwork as a student of the Department of Ethnology and Cultural Anthropology of the University of Warsaw.

Alongside observing religious ceremonies and conducting interviews, I also confronted my questions, hypotheses, and findings with Yezidi Hymnists, Qewals, a group of Yezidi people responsible for the transmission of oral tradition, living for centuries in the Iraqi villages of Bashique and Bahzani (especially Qewal Aryan Hasan Kochi, Qewal Ali Rasho Hasan Alhakary, Qewal Bahzad Sulaiman Sivo, Qewal Hameed Khalil Elyas, Qewal Qaid Rizgan), where I stayed in April 2018 and in October 2021 owing to the kindness of the families of Dalzar Nashwan Salem and Shwan Fareed Abdullah. I also discussed the issues that I was curious about with the religious elders and representatives of all the Yezidi castes – Sheikhs, Pirs, and Murids. I also had the honour of meeting twice with the aged Feqir Haji (d. 2019), from whose mouth I heard in 2014 one of the most important religious hymns, Qewlê Zebûnî Meksûr. In November 2018, I was given the honour of living in the house of a Yezidi religious leader, Extîyarê Mergê Bavê Şêx Xurto Hecî Îsmaîl (d. ←15 | 16→2020), and spending a whole week in Lalish itself during the autumn Festival of the Assembly (Cejna Cimayê).

In my attempt to comprehend the Yezidi religious tradition, I received invaluable help from the aforementioned leader of the Georgian Yezidis – Dimitri Pirbari – whom I have visited many times in Tbilisi and with whom I have travelled around Armenia in 2016 in a search for answers to my questions among the local diaspora. There too, I always met with the hospitality of the Yezidis and their selfless help.

While searching for materials for this book, I conducted field research in important places for the Yezidis, especially in Iraq (Lalish, Ain Sifni, Ba’adra, Bashique and Bahzani, Bozan, Alqosh, Sharia, Bartella, Duhok, Sinjar District), Turkey (Viranşehir and its surroundings, Xirbe Belek/Bozca, Bacin/Güven, Kiwex/Mağara, Şanlıurfa, Harran and its neighbouring area), Georgia (Tbilisi), Armenia (Aparan and the villages near Yerevan) and Germany (Oldenburg). The facts and impressions that I collected in those places during my conversations with the Yezidi people, while watching their religious life and appreciating their architecture, I also confronted in discussions with academics: Peter Nicolaus in Salzburg, Birgül Açıkyıldız in Mardin, Garnik Asatrian and Victoria Arakelova in Yerevan, Philip Kreyenbroek in Göttingen, Mammo Othman in Duhok, Pir Khadir Sulayman in Ain Sifni, Bedel Feqir Haji in Oldenburg, and the aforementioned Dimitri Pirbari and Kerim Amoev in Tbilisi. Thanks to funds from the Polish National Science Centre, I was simultaneously able to conduct library queries in such academic centres as Oxford, Göttingen, Yerevan, Diyarbakır, Mardin, Warsaw, Cracow, and especially Tbilisi, where I was able to access the collections of the extensive library and archive of the House of the Yezidis of Georgia. Recently, the world’s first International Yezidi Theological Academy (Akadêmiya Teolojiya Êzdîtiyê ya Navdewletî) and the first Department of Yezidi Studies (at the Giorgi Tsereteli Institute of Oriental Studies of Ilia State University) have also started operating there, bringing together researchers and students interested in the principles of the Yezidi religion.

During my field research, I also tried to take photographic records. I presented their effects at an exhibition entitled Let there be light! The cosmogonic festival of the Yezidis from the Iraqi Kurdistan, presented in Cracow and Warsaw, in the Asia and Pacific Museum. Some of them have also been used to illustrate this book.

While working on translations from Arabic, Persian, and Kurdish texts, I could always count on the guidance and help of Arabists, Irianists, and Kurdologists: Dimitri Pirbari, Dalzar Nashwan Salem, Talal Qarah Bolad, Rebaz Jalal Ahmed, Sholeh Paknejad Sahneh, Majid Hassan Ali, Hediye Yazdan Panah, Edyta Wolny-Abouelwafa, Mirosław Michalak and, of course, my wife, Magdalena Rodziewicz. Mention should also be made of Michal Bocian, who at the first stage of preparing this book provided an initial translation of most of the chapters, which I later reworked and expanded with new content. I would like to heartily thank them all, and at the same time apologise if I did not act upon all of their kind advice. I am solely responsible for any errors in the proposed translations.

←16 | 17→Finally, I would like to extend sincere thanks to the Yezidis for their help and hospitality. This book would never have been written if it was not for the kindness and support of: Farhad Baba Sheikh, Ismet Tahsin Beg, Dalzar Nashwan Salem, Nashwan Saleem Aswad and Naeema Simo Khider, Nawar Nashwan Saleem, Minaar Nashwan Saleem, Ghazwan Saleem Aswad and Dalghwaz Hassoun Simo, Shwan Fareed Abdullah and Maysam Murad Chicho, Faleh Hassan Jumaa, Hassoun Simo Khider and Hassna Jarrow Ibrahim, Daldar Saleem Aswad, Sheikh Abdel, Hussein Haji Osman, Sinan Gören, Kovan Khanki, Qewal Aryan Kochi, Jiyan Hassan Alkhalti, Amira Alfatey, Sheikh Khalet Hasan, Sheikh Nuri Shekhnamati, Sheikh Nadir Aloyan, Sheikh Rostam Amadov, Pir Maksim Darveshyan, Boris Murazi, Husein Rasheed Kishtu, Ilyas Yanç, Bedel Feqir Haji, Sheikh Xwededa Adani, and many others who repeatedly offered me their selfless help. Let me also thank my friends, dear colleagues, and the esteemed persons for their support and understanding shown to me during recent years, when I was devoted to the work on this book: Aleksandra Siudek, Włodzimierz Lengauer, Kazimierz Robak, Ewa Wipszycka, Marek Jankowiak, Mirosław Wylęgała, Magdalena Zowczak, Maciej Ząbek, Garik Grigoryan, Ziyad Raoof, Maciej Legutko, Katarzyna Witkowska, Katarzyna Prochenko, Alexander Sarantis, Julia Doroszewska, and Filip Doroszewski. Last but not least, I would like to express an especially heartfelt thanks to Peter Nicolaus, whom I met owing to our shared interest in Yezidism, and then to our joint research on Cejna Cemayê. I am immeasurably obliged to the Austrian for his friendship, knowledge and unflagging enthusiasm that made me persevere in the efforts to write this book. He was also its first reader.

Unfortunately, Professor Bogdan Składanek, the co-founder of the Department of Iranian Studies at the University of Warsaw, whom I was proud to call a friend, passed away before this book was published. He was very much looking forward to this moment and even during our last conversation he rushed me to publish it as soon as possible. He passed away at the age of 91, in May 2022. I had hoped to give him a copy of the book with a personal dedication thanking him for his hospitality, sense of humour, and, above all, the opportunity to get to know a real passionate scholar. Not being able to do this in the material sphere, I hope he will accept it in the sphere of thought, which by its very essence is not subject to death.

Note on transliteration, names, punctuation, quotations and dates

Most often, I use a simplified transliteration of terms. However, there are exceptional situations in which I want the Reader to pay attention to the original transcription. It applies especially to terms and quotations from the Kurmanji (Kurm.) dialect of Kurdish (Kurd.), which I cite in the Bedirxan script, and Greek (Gr.), Arabic (Ar.) and Persian (Pers.). As for the transliteration of Arabic and Persian, I use the system of International Journal of Middle East Studies, but I omit long vowels and diacritical marks, and in the Greek transliteration, I support myself with the Library of Congress Transliteration Chart, leaving out accents and aspirations.

The names of the Yezid castes (Sheikhs, Pirs, Murids) and special functions (e.g. Qewals, Feqirs), I write in italics and in capital letters when they apply to the whole group, and lowercase (e.g. sheikhs, qewals) when I refer only to its representatives. In both cases I usually use italics, unless those terms are a part of the individual name (Sheikh Adi, Qewal Aryan). Titles of all works and books, regardless of whether they are considered sacred or not, I write in italics.

I use the double quotation mark “…” when I quote a statement or give the title of a magazine or journal, and the single one ‘…’ when I refer to a specific term, concept and phrase. In turn, round brackets (…), are used in case of author’s additions (me or the one, I quote), and square brackets […] in case when the translator or editor interferes with the original text by supplementing or explaining it.

When quoting Greek and Roman authors, I refer to the critical editions by giving the name of the editor in round brackets and the pagination of the edition, e.g. Symposium (Burnet) 192e5–193a1.

Unless specified otherwise, dates refer to the Christian Era (AD).

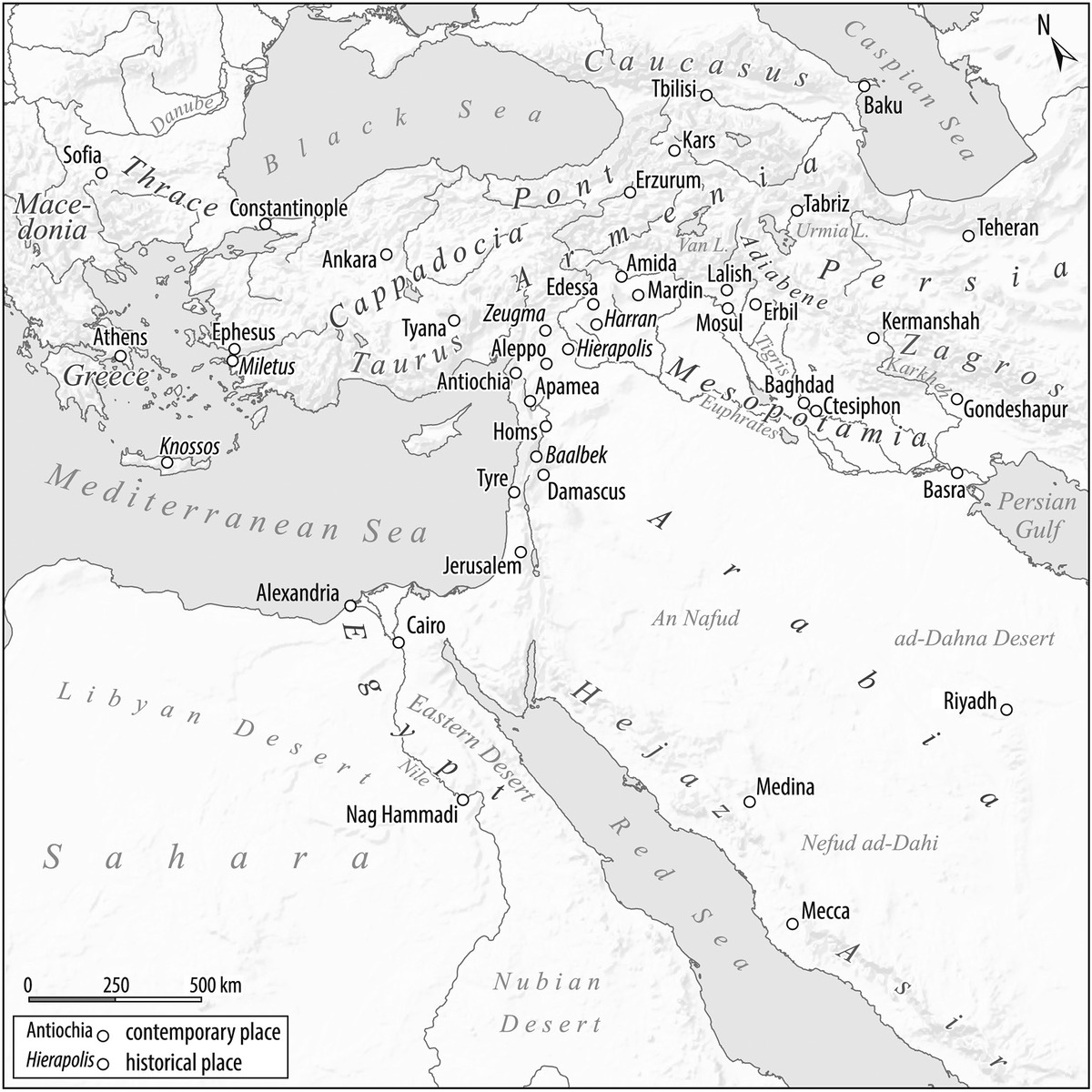

Territories and main places mentioned in the book

1. Introduction. Research problems and methodology

Since this book bears the subtitle The Yezidi Cosmogonic Myth at the Crossroad of Mystical Traditions, which demarcates its thematic scope, several terms used in it need to be clarified. Let me first explain what I mean by the adjective ‘mystical’ (Gr. μυστικός) by which I define the traditions of interest in this book, and why I focused on their ‘crossroad’. I employ this term in accordance with its Greek etymology and the sense it has acquired over the centuries, denoting what concerns the initiation (Gr. μυέω) into the greatest Mystery (Gr. μυστήριον; its Ar. and Kurm. equivalent would be سر and sur), that is, the process of discovering the Divine (esp. God), seeking direct experience of It and even union with It. He who follows this mysterious path, called a ‘mystic’ or an ‘initiate’ (Gr. μύστης), finds it either through theoretical contemplation of the Mystery, through participating in the mysteries (Gr. μυστήρια, ‘secret rites’) dedicated to It, or by combining these two methods.1 Over the centuries, many mystics have pioneered this difficult terrain and charted their own paths, the maps of which they have passed on to others. Some of these ways, most commonly used, over time have even taken the form of religions. Unfortunately, given the fact that the Mystery they are looking for “loves to hide itself,”2 to refer to the maxim uttered by one of them, the routes marked on the maps of their journeys go in different, even contradictory directions. Nevertheless, if we overlap them, we find the one place where they cross each other. Their point of intersection is also the only place that makes one wonder whether they do not in fact form a single radiating outwards path. The observation of this unique central point, where the mystics’ accounts on cosmogony converge, has constantly accompanied me while writing this book.

By ‘cosmogony’ I mean the origin of the cosmos or a story (Gr. μῦθος) about the process of the origin of the cosmos. The Greek term ‘κόσμος’, which I use in accordance with its meaning as it appeared in the oldest sources – that is, a beautiful arrangement of elements, a decoration – and was later refined by Greek philosophers to designate the ordering or assembling of various elements, so that they form a beautiful and independent whole.3 To highlight the unity of its elements, it can also be called the ‘Universe’ (Lat. universum), the ‘World’ and ‘Order’. ←23 | 24→Such a world is, for example, the Earth, Man (as Microcosm) as well as the set of all worlds (Macrocosm). In this book, when I write about ‘cosmogony’, it is the formation and origin of Macrocosm that I refer to by default, and if I make a reference to the formation of Microcosm, I explicitly state it.

The aim of this book is to describe a cosmogonic motif consisting of two threads, the Pearl and Love, which appear in the Yezidi cosmogonic myths, and to make an attempt to interpret them – both within the framework of Yezidism (the religion of the Yezidis), and by comparison with other cosmogonies that operate with similar threads. This will bring us closer to answering the question whether the motif can be deemed original or was borrowed. It will also facilitate formulating hypotheses about its possible origin. To achieve this goal, two attempts have to be made in particular: reconstruction of cosmogony of the Yezidis within which the said motif appears, and tracing the presence of parallel threads in other cosmogonies.

1.1. Problems with Yezidism

In 2019, Feqîr Hecî Şemo (b. 1924), one of the greatest authorities on the oral Yezidi tradition, who belonged to the illiterate generation and the illiterate tradition of Yezidism, died in Ba’adra. On two occasions, I had the opportunity to visit him in this Iraqi town, the former seat of the Yezidi Mîr (‘prince’, Ar. emir). Each time I had the impression that he embodied the dignity and mystery of the Yezidi religion. For many years, Feqir Haji had been an authority on theological and religious issues. Thanks to him many works of the Yezidi oral tradition have been preserved. The Yezidis, and especially his son Bedelê Feqîr Hecî, recorded his recitations and then published them in print.4 During the annual Festival of the Assembly, he was entrusted to play a key role in the sema’ ceremony, leading a procession of religious hierarchs around the fire that was lit in the courtyard of the main temple. When in the same year I talked about his death, or rather ‘changing the shirt’ (‘kiras guhorîn’, as say Yezidis who believe in reincarnation) with Dimitri Pirbari, the pir said: “It is an end to a certain era for the Yezidis.” The current shape of Yezidism and the knowledge about it are becoming increasingly tied to writing. The authority of a living person is slowly being taken over by the written word, or rather the text displayed by an electronic machine.

The multi-ethnic and multicultural origin of the Yezidi community, the caste system, hundreds of years of persecution, the religious taboo on literacy and increasing migration from their homeland have made it difficult to conduct research on Yezidism and answer the question: which elements belong to the original Yezidi tradition and which do not. Even among the Yezidis themselves, no consensus about it has been reached. In many cases, belonging to a particular tribe ←24 | 25→or caste determines the perception of the whole community and its history. For example, those of the Yezidis who belong to the very influential Shamsani group of the Sheikh caste consider themselves the descendants of ancient pre-Islamic traditions, especially Zoroastrian and Mithraic ones, and have a different attitude towards the presupposed Yezidi origins than others. In turn, the most numerous Yezidi caste, the Murids, who make up the vast majority of the entire population of the Yezidi people, possess less knowledge of the arcana of their own religion than the representatives of the two remaining castes – Sheikhs and Pirs (their very names denote ‘the elder’, in the sense of spiritual teachers). But also, many pirs and sheiks are not aware of some of the principles of their religion. As the author of the monograph The Yazidis, Their Life and Beliefs, Sami Ahmed wrote, “one must realize that the Yezidis, even the educated among them, know very little of their own doctrine, although they claiming otherwise. Their beliefs are in truth known to a very few men, probably not more than three or four (Baba Sheikh, Baba Gavan, and Baba Chawish), who are, in turn, not in agreement with each other regarding the dogma.”5 In this situation, the researcher faces a fundamental problem: – Which vision of Yezidism is closer to the truth? Is it the one presented by the few, or the one that is more common and widespread? This provokes even more questions: – Is it at all possible to speak about one truth and one Yezidism in this matter?

Caste differentiation entails another problem. Especially in recent years, the majority of Yezidi migrants to the EU countries or Russia, usually recruited from the caste of Murids. They are also susceptible to indoctrination and political propaganda. It proves to be most evident in the intense agitation carried out by politicians, who treat the Yezidis as a pawn in their geopolitical game. Furthermore, many murids, when confronted with various scientific and popular theories about their religion and culture, often either directly (as university students) or indirectly (through the media), uncritically accept them as facts and then reproduce them among members of their own community, granting them with a kind of ‘secondary identity’.6

An example of such a feedback mechanism can be found in the numerous attitudes that speak of the Zoroastrian or Mithraistic core of Yezidism, which are often based not so much on one’s own tradition, as on becoming familiar with the theories first put forward by Taufiq Wahby7 and later by Philip Kreyenbroek. Such theories even found support among representatives of the Yezidi aristocracy, as exemplified by the activities of Yezidi prince Mu’awiyah (the son of Ismail Chol), ←25 | 26→an author of To Us Spoke Zarathustra,8 who also founded a Yezidi-Zoroastrian Religious Society (Koma Ezdiya-Zerdeştiya) in Bonn. It is symptomatic that, for example, in the Yezidi religion textbooks, published by the Union of Kurdish Teachers (Yekîtiya Mamosteyên Kurd) in Germany, Zoroaster is presented as a Yezidi prophet,9 a phenomenon that can be observed especially among the German diaspora, which, in turn, has an increasing influence on the beliefs of other Yezidis.

Taking place in contemporary Yezidism, these processes cause of numerous internal conflicts and accusations against the Yezidi intelligentsia. Those concern mainly falsifying their religion. As Chaukeddin Issa, a Yezidi, wrote in 1997 in the Yezidi journal Dengê Êzidiyan (The Voice of the Yezidis), “It is sad and at the same time shameful that some members of the Yezidi religion are still trying to question our identities and origins. With this criticism, I am aiming in particular at the group of so-called intellectuals. (…) It was the pseudo-intellectuals who provided the outsiders, the non-Yezidis, with the breeding ground for the fruitless discussions of the last ten years.”10

One should also notice a huge number of false theories circulating among Yezidis on the Internet. While some are reproduced because of sheer ignorance and a wish to build one’s own identity (e.g., describing every ancient image of a peacock as a trace of the Yezidi religion), others result from intentional manipulation (e.g., extreme nationalistic websites that fabricate false anti-Kurdish statements imputed to the former Yezidi spiritual leader).

Some Yezidis support the theory of the original Kurdish identity of their milet, while others, on the contrary, reject any connection with the Kurds, pointing to the Arabic origin of their people, or even make a sign of equality between the Quraysh and the Yezidis. The fact that there exist such strong and opposing pressure groups among the Yezidis themselves shows that they are not certain – as a whole community of people defining themselves with the word ‘Yezidis’ – of their own identity. The Yezidis themselves are well aware of this problem. The issue is not entirely new, as in the history of this community, disputes between families of different genealogies have sometimes come to the fore, posing a threat of its disintegration.

Since I am speaking about this issue, I would also like the Reader to know my opinion on the ethnicity of the Yezidis. I am convinced that they meet the conditions to be considered a separate nation (constituted on the basis of a multi-ethnic community).11 This is particularly evident in: a) the self-declarations from ←26 | 27→many Yezidis, b) the binding caste structure in the community, c) the strict prohibition of exogamy, d) their own religion, e) their own political (Mîr) and religious (Bavê Şêx) power, f) their own historical territory and its own name (Êzîdxane/Êzdîxane),12 g) a coherent vision of parts of their own history, and h) their own anthropo- and ethnogenic myth that clearly distinguishes their milet from other.

Nevertheless, it is important to be aware that not all Yezidis consider themselves a separate nation, and some strongly identify with the Kurds. By the same token, it is even hard to say if we are dealing with one Yezidism, a single universal system of the Yezidis’ beliefs and practices, or rather with a few separate visions relative to the Diasporas in which they were originated and which are the more different from one another, the less they have contact with the old religious centre in Iraq. An example of such discrepancies can be Yezidis’ eschatological beliefs. Some Yezidis believe in reincarnation, others believe in Hell and Paradise, where the soul of the deceased is supposed to go, and yet another group do not see a logical problem in accepting both visions simultaneously. Obviously, it is possible to create a system in which these variants would not be mutually exclusive, but either this system does not exist at present (which does not exclude the possibility that it may have existed earlier), or it could be one of the many pieces of evidence that the Yezidi religion does not constitute a ‘system’ in the sense of the religions that have codified their principles in the form of some Summa Theologiae or Ihya’ Ulum al-Din. It is significant that, for example, among the Yezidis of Armenia and Georgia, there are festivals which are not celebrated in Iraq (e.g. Kuloça Serê Salê) and vice versa – one of the most important Yezidi festivals, the Çarşemiya Sor, has been forgotten by the South Caucasus diaspora and only recently there have been attempts to revive it. This diversity makes it necessary for the researcher of Yezidism to exercise great care towards any received information and to clearly note the place and the group that the person providing such information belongs to.

One of the factors that contributed to the said lack of unanimity among the Yezidis was the religious ban on the use of writing (with only one family being exempt) that used to be in force over the centuries. For ages, writing was considered a sin. Undoubtedly, this allowed the Yezidis to protect their religious secrets from non-Yezidis, but as a result, they do not have any holy Book that could be a kind of universal compendium of religious principles, so helpful when many of them live in diasporas isolated from the Iraqi centre. On a wider scale, the ban on the use of writing was abolished relatively recently, in the first half of the 20th c., when the Yezidis living in the Soviet dependent territories of the South Caucasus were subjected to the general education system. Apart from the Soviets, the gradual ←27 | 28→openness of the Yezidi people to contacts with non-Yezidis also had an impact on the lifting of this ban, especially the awareness that knowledge of writing allows not only to increase the level of education and economic advancement, but, above all, to save one’s own tradition from oblivion. Thus, a significant precedent was the publication of a book in 1934, which almost ten years earlier (in 1925) had been dictated by the illiterate prince of the Yezidis, Ismail Beg Chol.13 He had done so in full awareness and premeditation, in spite of the resistance of the Yezidi elders (just like when he sent his children to school), in order to “write down the principles of our religion and publish them in all European languages so that our faith would be known before it dies.”14

It is only in recent decades that the aspirations (answering to the need arising from the confrontation with other religions) to collect and catalogue in writing the corpus of religious output of the Yezidi religious poetry have emerged.15 This is especially true of the sacred hymns (qewls), which play a role comparable to that of the holy books in other religions. For several decades, Yezidis have been intensively recording and writing down their works of oral tradition. Nevertheless, even nowadays one can hear voices of disapproval towards the use of written word, which tells how strongly the ban has been rooted in the community.

A few extensive publications have been published in Iraq so far, including a transcription of several dozen hymns and prayers, to which Khalil Jindy Rashow and Pir Khadir Sulayman, who actively collaborate with the Yezidi qewals and the greatest authorities on the Yezidi oral works, especially Feqir Haji, have greatly contributed. The efforts to commit the Yezidi religious legacy into writing also come to the fore in the publications of the young generation of Yezidi academics, e.g. Kovan Khanki (Iraq), Dmitri Pirbari (Georgia), Bedel Feqir Haji and Khanna Omarkhali (Germany). The book of the latter, The Yezidi Religious Textual Tradition: From Oral to Written. Categories, Transmission, Scripturalisation and Canonisation of the Yezidi Oral Religious Texts, can be perceived as laying the foundations for the work on canonisation of the corpus of Yezidi religious works.

Apart from the lack of sufficiently developed sources, another factor that hinders the research on Yezidism undoubtedly lies in the hermetic nature of the community. The Yezidis are an endogamous group (of multi-ethnic roots), which neither accepts representatives of other ethnic groups in its community, nor does it allow religious conversion. Moreover, because of the secret nature of their religion, which is considered Satanism by representatives of neighbouring groups, the Yezidis have been facing hatred and persecution for centuries. Apart from minor ←28 | 29→incidents, they list over seventy (72, 73 or 74) acts of genocide that their community have suffered from. Incidentally, this number shows the strength of the influence of the ethnogenic myth among them. The Yezidis believe that they descend from Adam himself, while the other nations, in the number of 72, are the descendants of Adam and Eve. The number of genocides is therefore a symbolic assertion of the suffering experienced from all nations. Yezidis are filled with the greatest dread towards the Muslims, whom they fear not only because of the accusations of Satanism hurled by them, but also because of one of the interpretations of their ethnonym, which derives the Yezidis from the followers of an Umayyad caliph, Yezid ibn Mu’awiya. Yezid has gained poor reputation among the Muslim community as a man who broke the rules of Islam. Above all, however, he has attracted much hatred of the Shi’ites, who accuse him of murdering Husayn ibn Ali, considered the third imam by Shi’a people. Taking into consideration the acts of persecution which, for the reasons mentioned above, have been affecting the Yezidis, a researcher of their religion often encounters resistance from respondents while attempting to engage in sensitive topics and may not be given answers that they perceive as potentially threatening to the entire community. And even if he gains the confidence of his interlocutor and such answers are obtained, he is often bound by a word of honour that he will not make them public. Thus, the researcher faces a moral dilemma, whether to be faithful to an academic oath that obliges him to seek the truth and share it with others, or to be faithful to the word given to the interlocutors who trusted him.

Afflicted by an almost complete lack of written sources and historical data about their origins, the Yezidis – relying mainly on the myth of their forefather, Adam’s son – often consider their religion to be primordial and at the same time constituting the basis of other later religions. This becomes obvious if the original ‘Yezidism’ is to be simply understood as ‘paganism’ (in the sense of not belonging to any of the major religions), and if it is stated that the ancestors were once pagans. As Shivan Bibo wrote in a Yezidi journal “Lalish” published in Iraqi Kurdistan (original spelling):

The Izidies believe that they existed since ancient times. It is believed that the name “Izidism” conveys a religious more than an ethnic meaning on the basis of which they claim that in the past their kings reigned over various parts of the world such as Rome, France, India, Mongolia, China and Persia. The Izidies think that they had a great figure named, Peer Bob, who is believed by the Izidies to be Beelzebub. The Izidies also believe that Ahab – an Israeli king, Nebuchadnezzar, Ahasuerus – a Persian King, and Agricola of Constantinople and others were all Izidy Kings. Perhaps Izidies want to say that they belong to the primitive religion of humanity from which others separated because of schisms.16

←29 | 30→What can be stated about the Yezidi community without any doubt is that it bears a clear influence of Adi ibn Musafir, called ‘Sheikh Adi’ and ‘Shikhadi’, who as a Muslim mystic himself, had a significant impact on the Yezidi religion as its founder or reformer, or at any rate, to whom it owes to a large extent its present form. When asked if they knew any testimony about their religion prior to Sheikh Adi’s time, and how they would relate to the hypothesis that he was the actual founder of Yezidism, my interlocutors usually replied that Adi’s achievement was to put in order previous beliefs, which generally consisted in worshipping celestial bodies and the forces of nature. As Shivan Bibo writes further in the article cited above:

By the time Sheikh Adi appeared among the Izidies, Izidism, of course, was already there but was actually deteriorating because ignorance was descending upon the followers of this religion. (…) Soon after Sheikh Adi settled down in Lalish, he gathered the leaders and chief men of this community to enlighten them about their religion. Some Izidies were and are still known as Shamsanis i.e. the sun worshipers.17

However, there are also contrary positions. Many Yezidi people believe that ‘pure’ Yezidism is the one that has not been tainted by Sheikh Adi,18 and which would be the indigenous religion of all Kurds. One of the reasons for that may be an attempt to distance oneself from any connections with Islam, and thus from possible influences of Sufism, which was represented by Adi as the founder of Sufi order, tariqa al-Adawiyya. On a side note it should be added that Yezidis use the term ‘dervish’, ‘feqir’ and ‘qalandar’ to describe early mystics such as Hasan al-Basri and Mansur al-Hallaj (who were more concerned with practice than with the theoretical construction of religious doctrine), rather than ‘Sufi’, as they consider Sufism a purely Islamic movement from which they dissociate themselves. This particular linguistic sense can also be witnessed in their oldest religious works that belong to the oral tradition.19 As Pir Dima told me:

←30 | 31→Until Sufism was forced into the framework of Islam by al-Ghazali, it was a separate teaching of a gnostic and ascetic nature. They called themselves ascetics – derwesh, i.e., an ascetic. Later, a term tassawuf appeared. After some time, when some of the dervishes associated with the term tassawuf – Sufis – were recognised by the Islamic tarikats, i.e., brotherhoods, the Yezidis did not agree to this. They became dervishes separately, outside the framework of any religion. (…) The Yezidis (in fact dervishes – zahed – are ascetics, as they used to be called in the past) have great respect for the first greatest dervishes, such as Rabia al-Adawiyya, Dhul-Nun al-Misri, Hasan al-Basri, Bayazid Bastami, Junayd al-Baghdadi.20

During my fieldwork, I have also met with opinions of both Yezidi pirs and murids, who radically rejected the figure of Adi and everything connected with him, claiming that Yezidism is not a religion, but a “philosophy” related to practice, where the central role has been occupied by the cult of natural forces, which, in turn, dates back to the most ancient Mesopotamian traditions. These voices, although they contradict the historical state of knowledge, should not be ignored, as they are one of the contemporary trends shaping Yezidism.

A straightforward resolution to the issue of Adi ibn Musafir’s influence on Yezidism is also not facilitated by strong Kurdish propaganda, which uses Yezidism as a tool of cultural policy, presenting it as the original pan-Kurdish religion. This concept was particularly strongly promoted in the 1930s, as reflected in the speeches and manifestos of Bedir Khan brothers seeking a factor that would cement Kurdish identity. Making Yezidism the original Kurdish religion, which also contains elements of Zoroastrianism, would allow to ideologically bring together all Kurds and provide them with a distinctive identity and value based on the belief in their ancient origin. On a side note, the strength of this concept can be witnessed in the fact that it has met with approval also among the Kurds who declare themselves to be Muslims (such reactions I have also observed on numerous occasions in those parts of Turkish Kurdistan that are not inhabited by the Yezidis). The idea was also raised by the leaders of the political autonomy of Kurdistan in Iraq – Masoud Barzani and Jalal Talabani, who were seeking political support in the Yezidi territories. And even though the concept was not entirely fictional, since in the 14th c. some powerful Kurdish tribes indeed declared themselves to be Yezidis, it completely disregarded the fact that not all Yezidis were of Kurdish origin. Significantly, in the Yezidi community forming in the 12th and the 13th c., Arabs (and representatives of other ethnicities) constituted a considerable group. This fact, in turn, was emphasised during the rule of the Ba’ath Party in Iraq, when there were insistent attempts to Arabise the Yezidis by pointing to their connections ←31 | 32→with the Umayyads. Both Kurdisation and Arabisation had their advocates among the Yezidis themselves, which only exacerbated internal divisions in the community.21 Also today, supporters of either position can be equally met. This applies not only to Yezidis but also to those scholars who sometimes go beyond academic study to become involved in political propaganda.

The lack of clarity in relation to their own history is increasingly encouraging Yezidis to seek their roots and origin. And while they still refer to the ethno- and anthropogenic myth concerning the character of their mythical forefather, Prophet Shehid ben Jarr, the son of Adam, many are not satisfied with it. A good example of the quest to find their ‘scientifically proven’ origins can be an article printed in the already cited Yezidi journal “Lalish”, entitled Izidian Religion. Another Look, which expresses a very popular attitude among the Yezidis. It attempts to derive Yezidi roots from the Sumerians by listing “elements of similarity between the Izydian religion and the Assyrian and Babylonian religions which had the Sumerian origins”22 and formulating the following directive:

The Izydian religion is a very ancient one and its roots reach the Sumerian and Babylonian periods. To make sure of that we must study objectively and carefully the traditions and rites that Izydians are still keeping them and we must compare them with the rites, traditions and liturgies of other people that alternated the Izydians living in Mesopotamia.23

At some point, every researcher of Yezidism is confronted with the fact (devastating for a man educated in the Western scientific and academic paradigms) that the history of the Yezidi community functions simultaneously on several non-parallel levels. Mythical and historical themes intertwine here, but they often get tangled up and intersect to form a peculiar a-linear and a-chronological grid of connections. This is best seen in the case of the Yezidi holy figures, who have manifested themselves many times throughout history. As angels, they form relationships different from those they had as actual persons of this world. Therefore, obtaining particular information about a certain character from the Yezidi history is often connected with the vagueness as to which level it concerns. At the same time, the Yezidis themselves are often unable to indicate whether they refer to a myth or to specific ancient events, because the myth and the reality have formed a kind of amalgam, which is difficult to break down. The figures of two Yezidi saints, Sheikh Shams and Sheikh Fakhradin, can serve as an example here. They are considered brothers, sons of some Yezdina Mir. At the same time, they are identified with the two angels created by God at the dawn of time, as well as with the Sun and the Moon. Likewise, the former is considered to be a Muslim mystic ←32 | 33→from Tabriz living 1185–1248, whereas the latter was a Christian monk from the 7th c. Nonetheless, from the perspective of historical research, they are sometimes considered to be the sons or brothers of Hasan ibn Adi II (one of the then leaders of the Yezidi community, a relative of Sheikh Adi ibn Musafir) living in the second half of the 13th c. Such a multidimensionality of the Yezidi history shows the specificity of their thinking and its dominant principle of ‘emanationism’, but at the same time it hinders research for which the chronological aspect – as understood and assumed by European science – is important.

1.2. Problems with comparatism

The threads of the primordial Pearl and the world-forming Love make up the cosmogonic motif that is characteristic of the Yezidi myth of the creation of the world. Also, in the cosmogonies described by members of other cultures and religions connected with the area where Yezidism occurs, we can find parallel threads – either identical or similar enough to be considered their equivalents. However, only in a few cases do we notice the simultaneous presence of both elements, and even less often can we witness a situation where they constitute a single motif. Most often we encounter one of them – the Pearl, or something that resembles it, e.g. the Egg, or the Stone, that appears in the descriptions of the beginnings of the world. It also happens that some tradition refers to both similar threads, but they do not appear directly in the cosmogony, as is the case with early Christian literature, which, despite reaching for the symbolism of the Pearl, does not use it in a cosmogonic context, and despite declaring directly that “God is Love”, in the cosmogony described in the prologue to the Gospel of St. John, lacks any of the two themes of interest to us. The thread of the Pearl, or its equivalents, can be found in the cosmogonies known to other Middle Eastern religions, especially Yarsanism and Zoroastrianism, but in none of them has it been associated with Love seen as an active factor in the creation of the world.

This is why I paid special attention to those myths about the origin of the world in which the resemblance to the Yezidi cosmogony proves to be the greatest, such as those present in popular Muslim cosmographies, but particularly those written about by these Muslim mystics, who use both symbols pertaining to our subject, the Pearl and Love. However, it is important to be aware that their versions of cosmogony have never become the ‘official’ cosmogony of Islam. This is for the simple reason that neither the Pearl nor Love is mentioned in the cosmogonic context in the Quran.

Of the cosmogonies that have to some degree earned the title of ‘official’ in the sense that they are commonly associated with a given culture or religion, two in particular have a significant similarity to the Yezidi one. First, it is a cosmogony attributed to the Orphics, and second, a Hindu cosmogony (which, in turn, resembles the ‘Orphic’ one). Although the symbolism of the Pearl is not present in either of them, there is an element very similar to it – the Golden Egg and the ←33 | 34→Golden Embryo respectively – from which a deity associated explicitly with Love emerged.

Among the above-mentioned metaphysical traditions and religions – joined by others which I discuss further in this book – only Yezidism has made the motif of the Pearl and Love a permanent element of its cosmogony.

While comparing the threads in question, one has to remember about the difficulties that this process poses and the danger of over-interpretation. As the Reader will see in the course of further discussion, among the cosmogonies in which I will try to trace the parallel threads to the Yezidi cosmogony, the ones described by the Greeks and their late antique commentators (to which the Gnostics and the Sufis, in turn, also referred) occupy a special place. This is especially true of the cosmogony they associate with the Orphics. Such a juxtaposition is far from obvious, mainly on account of time and territorial distance between the Greeks and the Yezidis. It also causes complications in terms of methodology. In order to compare the Yezidi threads and the parallel Greek ones, the fact that the compared content comes from different eras, different cultural areas as well as different forms of expression has to be taken into consideration. In the case of the Yezidis, the comparative material is provided especially by their oral work,24 while in the case of the Greeks we have literature on our hands.

Details

- Pages

- 700

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783631881064

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783631884379

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783631880432

- DOI

- 10.3726/b19936

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2022 (December)

- Keywords

- Yezidism Mysticism Greek Philosophy Kurdistan Northern Mesopotamia Logos

- Published

- Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Warszawa, Wien, 2022. 700 pp., 12 fig. col., 85 fig. b/w, 2 tables.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG