The Narrative Power of Things

Consumer Culture in Contemporary Austrian Literature

Summary

With a focus on post-2000 Austrian literature, this book unveils how a skilful reading of consumer objects – both branded and non-branded – can enrich literary analysis. Introducing the concept of consumer literacy and applying it to Wolf Haas’ Das Wetter vor 15 Jahren, Thomas Glavinic’s Die Arbeit der Nacht, Arno Geiger’s Es geht uns gut and Raphaela Edelbauer’s Das flüssige Land, the study showcases the narrative power of consumer goods and the impact of Austrian literature and its writers on the idyllic national brand that stands in stark contrast to a troubled past.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 The Austrian Paradox, Past and Present

- Chapter 2 People, Places, and Things: Consumer Objects as a Literary Device

- Chapter 3 Consumer Objects, Consumer Literacy, and National Narratives

- Chapter 4 An Object on the Market: Austria as a Tourist Haven

- Chapter 5 Authorship, Texts as Products, and the National Brand

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

Acknowledgements

This was a labour of love, but one that would not have been possible without the support of the many amazing human beings I have the privilege of knowing – in academia and beyond.

I owe particular thanks to Dr Ben Schofield and Dr Katrin Schreiter, whose support, advice, and – above all – enthusiasm have made me grow both as a researcher and as a person. Thanks must also go to Professor Erica Carter, without whom I would have never found the courage to take on a project like this. Like her, my other colleagues at the Department of Languages, Literatures, and Cultures at King’s have been more welcoming and supportive than I would have ever hoped for and I will be forever grateful for it.

My most heartfelt thanks goes to my family and friends who have always been there when I needed them, who have believed in me when I did not, and whom I could not be more grateful for: first and foremost my supportive and patient husband Sighard Kammerlander and my parents Katja and Gerhard Wismeg, as well as my brother Mario. To my close friends Vera Stiegler and Nina Pauritsch, Sabine Koops, Hanna Gerhardt, Pascal Meinhardt, Constanze Schnee, and Felix Meyer zum Wischen, who all have supported me with patience, advice, and – most importantly – a generous amount of humour. Thanks also goes to Patricia Volhard and her team whose trust and support has been invaluable.

Thank you all for being who you are.

INTRODUCTION

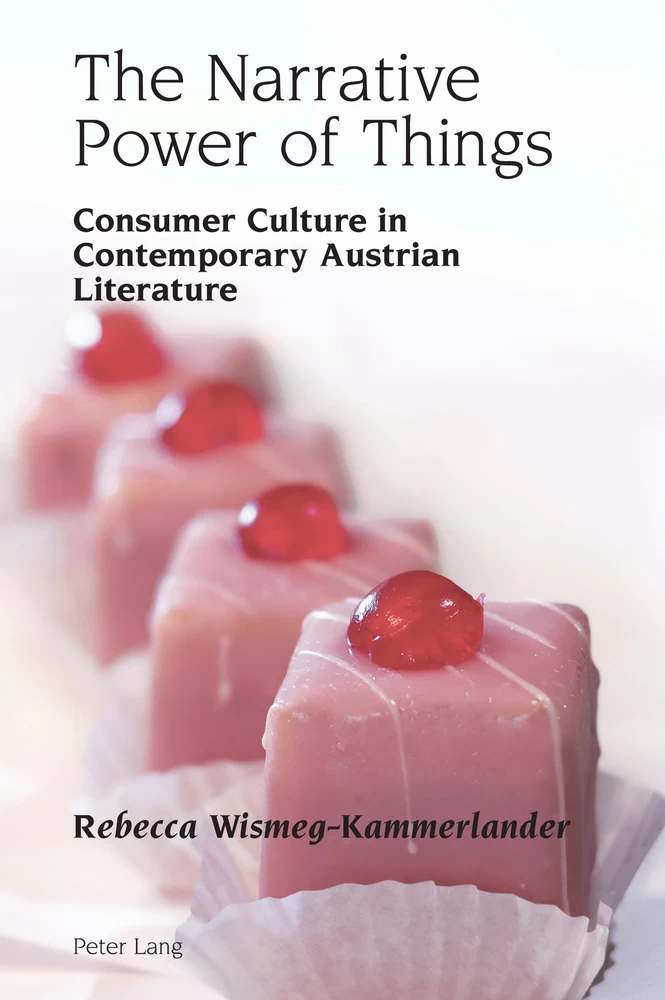

A Sweet and Shiny Surface: Consumer Literacy and the Nation

If asked to imagine a ‘quintessentially Austrian’ moment, then taking a seat at the iconic Café Landtmann in Vienna, ideally with a view of the neighbouring Burgtheater, and enjoying a Wiener Melange and a glistening, pink Punschkrapfen, could surely rank near the top of any list. Yet in this image it is neither the grandeur of the nineteenth-century architecture nor the smell of freshly brewed coffee that best encapsulates the ‘inherent Austrianness’ of the scene. Instead, it is the pastry confection that needs to be looked at more closely. For the Punschkrapfen is, in fact, a polemical and immensely fitting symbol for Austria: a sweet, shiny surface, immaculate and eye-catching, from underneath which, after only one bite, a brown mass of commingled, alcohol-drenched leftovers emerges. As Robert Menasse puts it:

Er ist außen rosa, innen braun. […] Daß der Punschkrapfen als Symbol für die Zweite Republik gelten kann, funktioniert nur auf der Basis von zwei Voraussetzungen: Erstens ist der Punschkrapfen tatsächlich ein zwar unwesentlicher, aber doch irgendwie typischer Bestandteil der österreichischen Lebensrealität. Zweitens muß dessen Beschreibung zumindest ein minimales historisches Wissen ganz selbstverständlich evozieren, in diesem Fall die historische Bedeutung der Farbe Braun.1

In his view the Punschkrapfen reveals the literal sugar-coating of the unsightly facets of Austrian history and identity; an image of Austria conveyed by a consumer product, yet one that requires a basic understanding of its context (in this case of Viennese Kaffeehauskultur and of the encoded, political meaning of the colour brown and its links to fascism), so skills in consumer literacy, to decode.2

Menasse’s image of the Punschkrapfen suggests that consumer goods can hold important symbolic value; a concept which stands at the heart of this book. Contemporary literary texts are strewn with an array of consumer objects, which should, as the example above suggests, be seen as more than clutter, more than meaningless accompaniments of our everyday lives. Instead, these objects fulfil crucial functions: they bring symbolic value to the texts where they frame characters, introduce stories, and engage with national narratives. Exploring the symbolic value of these objects encourages us to ask how identities can be constructed, how memories can be passed on, and how the image of a nation itself (as in Menasse) can be conveyed, critiqued, and transformed by literature. This study thus aims to develop a narrative approach to consumer literacy and to apply it to a corpus of post-2000 works by the Austrian authors Wolf Haas, Thomas Glavinic, Arno Geiger, and Raphaela Edelbauer. In so doing, it explores how this consumer literacy unlocks the narrative charge and symbolic value of consumer objects in contemporary Austrian writing, and how this unveils the extent to which images of ‘Austrianness’ pervade these texts and bring forth a multifarious image of the national brand of Austria – a brand that, just like the Punschkrapfen, seems to not entirely lose its appeal, even after one has had a glimpse at what lies at its core.

Towards a Theory of Consumer Literacy

Unlocking the narrative value of consumer objects and analysing their impact on and function within texts requires what I described above as consumer literacy. In the social sciences, this term describes “a combination of skills, knowledge and engagement”3 that is needed for consumers to make sensible choices, which could ultimately empower them. In applying this concept to literary works, I retain the interest in the ‘knowledge’ and ‘engagement’ required to ‘read’ products and goods but shift my focus towards the narratives with which consumer objects (branded or not) can be charged. Authors, I argue, regularly rely on consumer literacy when they make deliberate choices about the objects they introduce to their texts, where they then influence the way characters, families, and, as will be shown, nations are presented to the readers. Equally, readers draw on consumer literacy when encountering them in texts, no matter whether they deliberately seek to examine the role of consumer objects or not. The successful application of consumer literacy in either setting, however, is, as findings from research in the social sciences suggest, dependent on a certain level of knowledge and engagement.4 The reader has to be informed and needs to recognise the narrative value of the consumer objects and brands mentioned to minimise the risk of overlooking the at times subtle strands of narration that are brought to the texts through consumer goods. Knowledge of the cultural context within which the consumer objects are charged with meaning is a particularly important factor, especially when aiming to decipher specific undertones such as those tropes of ‘Austrianness’ that will be traced here. An active engagement with consumer objects and their origin and cultural contextualisation is thus called for.

The form of consumer literacy developed throughout this study is a way to respond to these crucial demands and draws on research into culture and the role of consumer goods. Central to this concept has been the work of anthropologist Grant McCracken, who argues that consumer goods play a crucial role in the transfer of meaning within cultures, with his particular focus on how objects get charged with meaning and further pass this on to the individual consumer by rituals of consumer culture.5 This deep embeddedness of consumer objects in processes of meaning transfer, with the individual consumer as a preliminary end point, proves fruitful for the approach taken here, as consumer objects emerge as essential tools for the construction and narration of individual identities. The question of how identities are shaped and narrated, however, should not remain limited to the individual. While theories of material culture developed by Robert Dunn,6 Eva Illouz,7 and Robert Misik8 each address the role of consumer objects in the construction of individual identities within specific settings, research undertaken by Daniel Miller, who argues that consumer choices shape social relations,9 takes this further. Drawing on this, my application of consumer literacy to literary texts also yields answers to bigger questions about the identities and (self-)stylisation of groups, such as families, within which consumer goods circulate, transferring meaning and memories between generations,10 and ultimately the nation, which itself can become a good to be consumed. In this context, a further dimension of McCracken’s approach underlies my own: his argument that the meaning a consumer good ultimately carries is inextricably linked to the culture within which this meaning has been generated. Tracing consumer goods and their cultural backgrounds in the texts of my corpus and applying consumer literacy to them thus also allows for the discovery of elements of ‘Austrianness’ that consumer objects carry, and which are consequently (re)introduced to the novels. This reading in turn helps to analyse the status of the national brand of Austria and its position within contemporary Austrian literature.

The concept of national branding is based on theories that have been developed in particular by Wally Olins,11 Melissa Aronczyk,12 and Keith Dinnie,13 and that relate to a nation’s active attempts to manage its reputation through branding and advertising efforts. While this clearly is a factor in the Austrian case, underpinned by its recent image issues and the Kurz governments’ overt attempts to employ marketing strategies to overcome them, this is, as my analysis will show, only one side of the coin. An engagement with voices which are heard within Austria and beyond, who engage with the nation and its issues despite not being part of a deliberate, officially-steered branding effort will reveal that the national brand of Austria is, despite its prominent overtones, much more than the mere result of campaigns full of tourism imagery. Critical voices too have an impact, scandals scratch neat surfaces and reveal what lies beneath, and what ultimately emerges is the product of a multitude of interrelated processes; a conglomerate of branding and public discourse, of scandals and tourism campaigns, of memory culture and not at least of literature.

The importance of consumer objects and their aesthetic function within literature has itself become a field of study in recent years, not least as a result of the research of Catriona MacLeod, who engages with sculpture and its meaning within the literature of the Romantic period,14 and most recently of Bettina Bildhauer,15 who approaches Medieval literature from the perspective of objects, examining their agency. In the early 2000s, fuelled by the rise of Popliteratur, a focus on consumer culture and its objects also drove research focused on contemporary writing: further developing the term ‘Warenästhetik’ as coined by German philosopher Wolfgang Fritz Haug in 1971,16 a concept deeply critical of capitalist processes and the utilisation of aesthetics for their expansion, Germanists like Moritz Baßler17 and Heinz Drügh,18 as well as art historian Wolfgang Ullrich19 have explored the impact consumer objects along with their branding and advertising can have on literature and the arts. Drügh identifies two core strands of inquiry which inform current thinking about consumer objects and their role in the arts: first, an approach from the angle of material culture, concerned with the cultural meaning and practices relating to and encoded in consumer objects, and secondly a focus on the aesthetics of consumer goods that is interested in the input “den die Warenfluten der Konsumgesellschaft für bestimmte Literatur- und Bildästhetiken liefern”.20 In this book, I will take an approach that seeks to unify both those strands, recognising that a consumer object’s narrative value, in particular with regard to national brands, is significantly shaped by their cultural meaning.

Thus, in analysing the role of consumer objects in texts of Haas, Glavinic, Geiger, and Edelbauer in a series of close readings, it is my aim to demonstrate the applicability and potential of my iteration of consumer literacy within the field of German and Austrian Studies. I will identify and closely examine consumer goods and their function as narrative assets in two key areas: first, their capacity as elements of identity construction on the level of individual characters, of families, and of the nation; and secondly their role as signifiers of a wider ‘Austrianness’. For the latter, my application of consumer literacy expands beyond the analysis of consumer goods within the texts. On the one hand, I examine Austria as a tourist destination, hence as a marketed consumer good itself. On the other, I explore how the authors whose work makes up the corpus discussed here are themselves marketable figures. In the latter case I will draw on analytical perspectives developed by Rebecca Braun, who has undertaken significant steps in developing new approaches towards questions of authorship by looking at celebrity and world authorship,21 and Anke Biendarra, who examines contemporary German-language writing against the backdrop of globalisation.22 Moving from the close reading of products in literature to an analysis of the function of authors and texts as products, this study thus demonstrates the power of consumer literacy as both a narrative tool, and as a means with which to explore how and where Austria is represented within and through literature.

Where Is Austria?

A snapshot of Austria in late 2020, at the time of completion of my research for this book, shows it grappling with its image, not least trying to repair the damage done by the inglorious role of Ischgl, a hotspot of winter tourism, as “a Covid-19 ground zero”.23 This proves to be a situation emblematic for the post-2000 moment in which Austria’s image as a tranquil, impeccable tourist haven has been repeatedly called into question. Beginning with Jörg Haider’s rise to political power and his subsequent entry into government in 2000, an international discourse about Austria’s condition has been reinvigorated, leaving the country’s reputation in turmoil. Further fuelled by the troublesome 2016 presidential election, resulting in only a narrow defeat of the right-wing FPÖ candidate Norbert Hofer after three rounds of voting, the election of Sebastian Kurz, the subsequent participation of the FPÖ in his coalition government only a year later, and the series of scandals that followed – among them the infamous 2019 Ibiza affair – Austria continues to find itself at the centre of unwanted attention, a situation reminiscent of the aftermath of the Waldheim affair in the 1980s.24

The latter led to an in-depth engagement with Austria’s self-stylisation and its suppressed Nazi past in the literature of the time. Authors like Thomas Bernhard, Robert Schindel, Michael Köhlmeier, and Elfriede Jelinek drew unabashed pictures of the nation, showcasing the stark contrast between who Austria was and whom it wanted to be perceived as – and they continue to do so.25 The work of authors of Jelinek’s generation, contemporary witnesses of the Waldheim affair and writers who had already begun their careers at the time, and their contemporary approach towards Austria’s image has been the subject of many significant studies – Katya Krylova traces continuities of Austria’s dark legacy to the present day and expands her approach by also examining film and memorial culture,26 while Allyson Fiddler examines Austrian literature, film, and music in the nexus of resistance against the far-right in the post-2000 moment, and Gundolf Graml specifically hones in on the role of Austria’s tourism industry and thus consumer codes for its identity construction and literature. This deep connection of Austria, its culture, and consumer objects, also emerging in the form of its own commodified character, has also been acknowledged by historians like Oliver Rathkolb, who examines Austrian history, recognising the heightened importance of consumer culture in recent years,27 cultural historian Anthony Bushell, who foregrounds tropes that shape both literature and the national brand of Austria in his work,28 and author and public intellectual Robert Menasse, who takes a polemical stance when discussing Austria’s self-stylisation and its sheer endless will to please its guests.29 And yet, despite these approaches and although research has been carried out with an aim to identify the role of consumption within the realm of Austrian nation branding,30 a specialised analysis of Austrian literature with a focus on the role of consumer objects has not yet been undertaken. Recognising the narrative value of consumer objects and the methodological promise of consumer literacy allows for an expansion of these approaches, developing our understanding of Austrian writing as well as its inherent elements of Austrianness in selected works from post-2000 authors.

The corpus of texts that will be addressed has been written by authors whose careers began after or close to the turn of the millennium, which has, as argued above, been a watershed moment for Austria. The focus on these younger writers and newer texts will allow for a study of literature that is not directly and expressly connected to the writing of the Waldheim-era. Beginning a career around the 2000s also implies that the authors have entered into a literary industry that has taken on methods and expectations in terms of authorial (self-)marketing which diverge from those of the 1980s, in particular through the rise of the internet. Additionally, with the aim of uncovering an essence of ‘Austrianness’ through the application of consumer literacy, it is notable that the authors examined here have grown up and been socialised in Austria; their work is set in and/or deals with Austria; and they themselves are marketed as Austrian writers and are perceived as such by readers, the feuilleton, and cultural bodies such as prize juries.

Wolf Haas, born in Maria Alm am Steinernen Meer in 1960, came to fame with a series of crime novels centred around the unorthodox investigator Simon Brenner in the late 1990s. The Brenner novels (1996–2022) as well as a number of subsequent texts published by the author have found commercial success, critical acclaim, and the attention of researchers. The latter mainly focus on his unusual tone of voice and writing style,31 the meta-fictionality of a number of his novels,32 and the overt authorial self-stylisation in his texts.33 What stands out as a connective element linking the entire body of his work and what still remains underappreciated is his prominent utilisation of elements of ‘Austrianness’: the noteworthy idiom used by the narrator of his popular Brenner series is strongly influenced by Austrian undertones, with his fictional self, appearing in Das Wetter vor 15 Jahren (2006), Verteidigung der Missionarsstellung (2012), and most recently Junger Mann (2018), repeatedly reflecting on being Austrian. Meanwhile, and of specific interest for this study, symbols of Austrianness, often in the form of consumer objects, permeate every narrative layer in each of his texts. Haas has a central role here, with Das Wetter vor 15 Jahren serving as a ‘red-thread’ that connects all my chapters. This 2006 novel, written in the form of an interview between Haas’ fictional self and a journalist from the feuilleton, the Literaturbeilage, lends itself particularly well to a reading through the lens of consumer literacy. Consumer objects stand at the core of both the interview and the embedded meta-narration, where they impact the construction of characters, raise issues of belonging, and, most importantly, introduce narratives of Austrianness. The latter inform the self-stylisation of the fictional Haas as well as the statements he makes about his novel specifically and his work as a writer more broadly, thus offering an opportunity to examine the ways in which this ‘author character’ also can be read as an Austrian consumer good. Like this fictional iteration of Haas, his real-life counterpart is well aware of his status as an Austrian author. Embedded in a network of Austrian literature and popular culture and with roots in both academia and advertising, he embraces the features of Austrianness that have framed his career and inform the way his author brand is perceived.

Thomas Glavinic, born in 1972, is also an author who overtly plays with his self-stylisation, blurring the borders between fact and fiction through his writing and his presence in social media. His texts too have been subject of academic study, often addressing his discourses of fear, isolation, and fatalism34 as well as his auto-fictional writing and authorial self-stylisation.35 Unlike Haas, he initially does not appear to embrace his Austrianness; instead he tends to describe it as a form of defect he has to overcome.36 Nevertheless, he too has a firm footing in the network of post-2000 Austrian literature and popular culture and does not shy away from taking on, for example, the role of a brand ambassador for Dachstein, an Austrian outdoor shoe brand, or from writing a column for the Austrian lifestyle magazine Wiener. This association with consumer objects and brands with an explicit Austrian background is not only an aspect of his authorial self-stylisation but also an important facet of his writing. His 2006 novel Die Arbeit der Nacht follows Jonas, a Viennese Einrichtungsberater, from the fateful morning he wakes up to an entirely deserted city37 to his suicide a few months later. Existing research relating to this text mainly focusses on the novel’s apocalyptic, dystopian setting as identified by Hans Wagner38 and Silke Horstkotte.39 Furthermore, Felix Forsbach has approached the text from an angle that examines the protagonist’s use of media with an aim to (re)assert himself of his own existence,40 an approach that will be expanded upon, as it is not only media that Jonas employs in this way, but consumer objects more broadly: even in a setting of complete isolation, and faced with the absence of other humans to interact with and who could serve as an audience for his self-stylisation, consumer objects retain a major role in the protagonist’s life. They serve as a means of orientation, they help Jonas to maintain a sense of self and to revive memories, and they accompany him up until his death. A closer look at the consumer objects the protagonist engages with and the shape this engagement takes will show how, through the Austrianness encapsuled in these items, his sense of self relies on Austrian narratives, which are in turn an essential facet of Glavinic’s writing.

In Es geht uns gut, Arno Geiger’s (born 1968) prizewinning 2005 novel, the reader is introduced to another young Viennese man, Philipp, who also faces problems brought about by loss. Unlike Jonas in Glavinic’s Die Arbeit Nacht, however, Philipp is not forced into isolation and is not alone. Instead, he inherits his grandparents’ mansion in Hietzing along with all its contents and is now compelled to handle the estate – a task that appears insurmountable to him. In this novel consumer objects fulfil a further crucial narrative function: they carry memories and are charged with stories of different generations of Philipp’s family; narratives that are ultimately lost due to the heir’s failure to engage with their carriers. This lack of consumer literacy – or unwillingness to apply it – means that an intergenerational transmission of memories cannot take place. Since active communication in the family has broken down decades earlier, the negligence displayed towards the consumer objects (which are ultimately discarded in bulk) means that a last opportunity to salvage an intergenerational connection is lost. Crucially, the narratives that are introduced through the use of consumer objects by Geiger guide the readers’ attention towards tropes that have been prominent in Austrian literature for decades: forgetting and the evasion of the past. This is also the topical lens through which Es geht uns gut has mostly been read, for example by Julian Reidy, who discusses the impossibility of remembering expressed in the novel,41 or Michelle Mattson, who puts these issues in the context of gender questions.42 Geiger’s success following the award of the inaugural German Book Prize has not only made him commercially successful, it has put him on an international stage. His texts, including a much-debated memoir dealing with his father’s dementia,43 repeatedly revisit the issues of forgetting and repression that are prominent in Es geht uns gut, which in turn are addressed in criticism.44 Geiger’s deliberate use of consumer objects as vehicles of memory in Es geht uns gut, however, has not been sufficiently studied and his footing in well-established tropes of Austrian literature as well as his renown as a post-2000 Austrian author make him and this novel conducive objects of study within the framework of this book.

That the failures of memory culture and the repression of Austria’s Nazi past have not ceased to occupy the minds of Austrian writers is, beyond Geiger, further proven by Das flüssige Land, the 2019 debut novel of Raphaela Edelbauer (born in 1990). The acclaimed text, shortlisted for both the German and the Austrian Book Prize, contrives an apocalyptic scenario in which the supressed past becomes a physical threat to a superficially idyllic Alpine town. Due to its recent publication, no critical work on Edelbauer exists at the time of writing. Because of her success, however, the feuilleton has engaged with her and her work repeatedly, foregrounding her Austrianness,45 for example, by discussing an iconic photograph of chancellor Kurz with her on Deutschlandfunk Kultur,46 and her interest in Austria’s handling of the country’s history.47 The latter emerges as a crucial theme of Das flüssige Land: the novel focuses on a town that rests atop an unstable shell of ground, hollowed out by mining, and later the establishment of a subterranean Nazi arms factory, at risk of collapsing into nothingness at any minute. And yet, the townsfolk are preoccupied with restoring the outer appearance of their village while refusing to – quite literally – get to the bottom of the abyss that endangers them. The events that unfold once Ruth, Edelbauer’s protagonist, arrives in the town and makes a first advance towards dealing with the past draw a polemical picture of Austria, and focus on the nation’s self-destructive urge to market itself as a consumer good. An application of consumer literacy to Das flüssige Land allows for a reading of Austria as a consumer product, revealing crucial facets of its national brand.

The Shape of Things to Come: Chapter Outline

To allow for a fruitful application of consumer literacy to the texts that make up the corpus examined here, Chapter 1 probes more deeply into Austrian culture and history, and, in particular, identifies crucial narratives carved out by figures such as Rathkolb, Bushell, and Menasse on how the nation’s (self-)stylisation, image, and cultural production have been determined and are disseminated. The narrative of victimhood and the directly related repression of Austria’s Nazi past are part of this set of narratives to be explained and explored just as much as its self-stylisation as a Habsburg museum and nature reserve, and the focus on its solipsism and conservatism. This is followed by a longer analysis of critical research on the role of consumer objects as markers of identity construction, deepening the approach I have begun to outline in this introduction and providing insights into the processes and strategies that make consumer objects suitable tools for the construction of identities on an individual level, retuning in particular to cultural approaches in Baßler, Dunn, and Misik, as well as on a larger social scale, as used by Olins and Aronczyk. The chapter thus explores how consumer objects, branding, and consumer literacy construct a national brand of Austria, providing a foundation for my exploration of how these are manifest in post-2000 literature in my subsequent chapters.

In Chapter 2, Haas’ Das Wetter vor 15 Jahren is brought into conversation with Glavinic’s Die Arbeit Nacht with the aim of examining how consumer objects are used by the authors in order to construct and narrate individual identities. Taking a close look at a range of products through the lens of consumer literacy, my interest here is in the fundamental power of seemingly insignificant objects – an inner-tyre tube, a lipstick, a Luftmatratze – for the construction of a self-image, and how these can be and are read by others. Glavinic’s novel serves as a powerful counterpoint to Haas’ dialogical novel, as the protagonist here does not find any human to actively engage with. However, his skills in consumer literacy help him to imagine the lives and personalities of others by engaging with the items they have left behind: consumer objects give the ‘loner’ a feeling of control and support him in his attempts to maintain a sense of self that now needs to be maintained without external feedback and interpersonal exchange.

Chapter 3 extends my focus beyond the individual, reading Das Wetter vor 15 Jahren alongside Geiger’s Es geht uns gut. Here consumer goods are situated in a broader nexus of consumer culture, literature, and memory culture. In Geiger’s novel a Meinl coffee tin that gathers dust in an attic, Biedermeier furniture that stubbornly resists its removal, and a cannon ball placed at the heart of the mansion serve as vehicles of memories of different generations of the same family. Tracing the items’ biographies, their placement within the family’s history of which they are a part, and engaging with their handling by Philipp reveals the crucial role consumer objects can play in telling stories of disconnection, forgetting, and repression that sit strongly within Austrian literary traditions. Meanwhile in Haas, a collection of smuggled goods hidden in a den in the mountains reveals unexpected histories, which also draw a picture of Austria that breaks with that of the tourist idyll.

The latter theme is developed further in Chapter 4, which addresses the ways in which Austria itself is presented as a consumer object in Edelbauer’s Das flüssige Land and Haas’ Das Wetter vor 15 Jahren. What emerges is a playful and subtly critical engagement with the trope of Austria as a tourist idyll in the case of Haas, while Edelbauer’s novel conjures up a much more devastating and dystopian picture of the nation. In both cases, as will be shown, the full narrative potential of this deliberate depiction of Austria as a consumer good can only emerge if consumer literacy, especially in terms of contextual knowledge, is applied. Both works reveal in different ways how lived reality deviates from the idealised brand image that is constructed and distributed through the channels of tourism marketing.

Having moved from the individual through the familial to the national, Chapter 5 takes a step beyond the literary worlds of the texts themselves, and analyses each of the four authors in the corpus to see how their respective author brands are constructed, and how these relate to Austria and its ‘national brand’. Understanding how these authorial figures, alongside their texts, are advertised and marketed through their own agency as well as through that of third parties within a wider literary network, provides us with an innovative account of how author brands in Austria are constructed. In so doing, I argue that the author brand itself, like the novel, must be seen as a consumer good, consumed at home and abroad, leading us to explore the extent to which these authors and their texts can themselves shape the national brand of Austria and its reputation.

1 Robert Menasse, Das war Österreich. Gesammelte Essays zum Land ohne Eigenschaften (Vienna: Suhrkamp Verlag, 2005), 47–48.

2 Menasse, Das war Österreich, 47–48.

Details

- Pages

- X, 294

- Publication Year

- 2023

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781800797611

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781800797628

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781800797604

- DOI

- 10.3726/b19414

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2023 (October)

- Keywords

- Contemporary Austrian literature consumer culture and consumer aesthetics identity construction and narration The Narrative Power of Things Rebecca Wismeg-Kammerlander

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, New York, Wien, 2023. X, 294 pp., 8 fig. col.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG