Nationalisation of the Sacred

Orthodox Historiography, Memory, and Politics in Montenegro

Summary

Nationalisation of the Sacred offers a detailed analysis of the theological backdrop to these conflicts. It analyses how various strands of Eastern Orthodoxy have adapted to the contemporary political context, a process where history, memory, and politics are transformed to fit the needs of rival nations and churches. The book provides an in-depth analysis of this process and the transformations in church-related conflicts in post-communist Montenegro, where the Serbian Orthodox Church has been pitted against a rival Montenegrin church and Montenegrin government.

Additionally the book provides an up-to-date and unique analysis of Eastern Orthodox historiography, modern Serbian theology, religion in Montenegro more broadly, and the roots of the violent clash between Orthodox believers and the Montenegrin government in 2019-2021.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Titel

- Copyright

- Autorenangaben

- Über das Buch

- Zitierfähigkeit des eBooks

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgement

- Notes on terminology

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- The creation of a new religious and political landscape of Montenegro

- The desecularisation of Yugoslav politics

- The “root” of the rising Serbian nationalism

- The study of the ideology and practice of history writing

- Nationalism and religion: The same order?

- Studies of saints and sites

- Key concepts and sources

- Eastern Orthodoxy in Montenegro and former Yugoslavia

- Slavic migration and medieval churches

- The rise of the Vladikas

- The Orthodox Church in independent Montenegro and Yugoslavia before 1989

- The Serbian Church in Montenegro from 1989

- The creation of the Montenegrin Church

- Rising conflict between state and church

- Head to head in 2019–2020

- Challenging the state framework

- The Eastern Orthodox ideology of history writing

- Towards Eastern Orthodox historiographical orders

- The development of state-centred historiography: The Eusebian history of salvation

- The dismantling of a state-centred historiography

- Athanasian historiography today

- The making of Serbian Orthodoxy in history

- Njegoš’s notion of history and the Divine

- Velimirović and the return to St Sava

- Popović: Orthodoxy beyond the confinement of the state

- Amfilohije and the embodiment of salvation

- Saints and place-making in Montenegro

- The cults of Jovan Vladimir

- The cult of Duklja

- The sainthood of Petar I

- Canonising Petar II: Njegoš

- Saints, neo-martyrs and the forgotten tombs

- The creation of cults

- Outlook on the politics of history writing in Eastern Europe

- North Macedonia: The history of the Archbishopric of Ohrid revisited

- Bulgaria: The homecoming of national neo-martyrs

- A final outlook to Ukraine: From brotherhood to division

- History and memory

- Towards a theory of nationalisation of the sacred

- Towards a definition of Orthodox historiographical practice in Montenegro

- Religious ideology

- The history of the saints or the nations?

- Bibliography

- Index

Preface

When Thou hast created the Mind

It did not see you, Myopic and Blind

Thou are an endless Ocean

I, an Oarless Boatman

– Njegoš, ruler and metropolitan of Montenegro

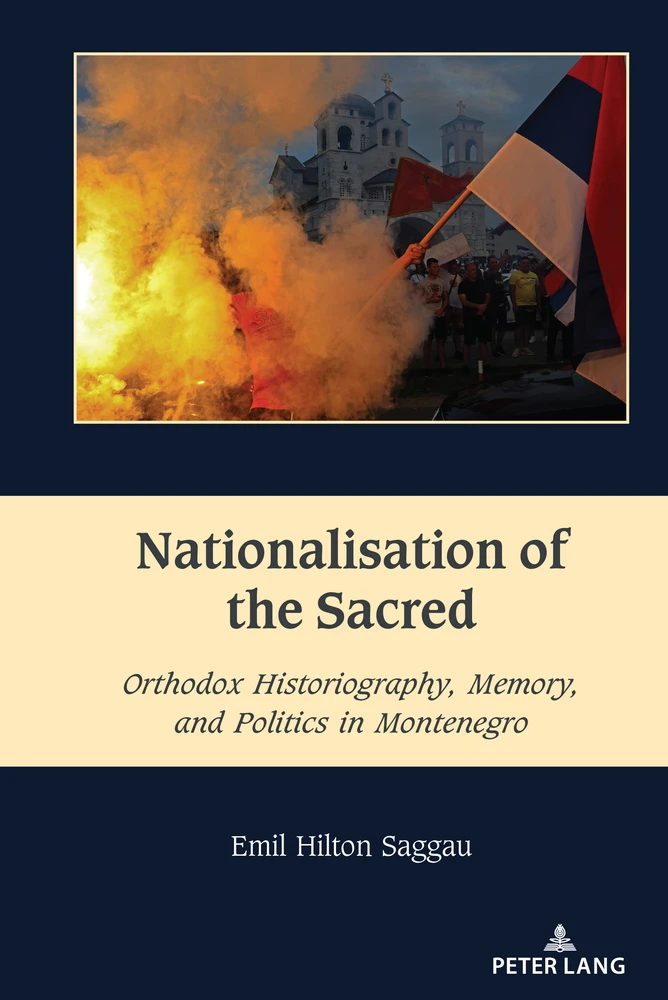

Montenegrin nationalist blocking the road to Cetinje during the enthronement of a new Serbian Orthodox metropolitan of Montenegro, 5 September 2021 (Photo: Savo Prelevic, AFP)

In my first piece on South Eastern European religion from 2011, “A journey at the periphery of the European mind”, I argued that the region of South-East Europe is the very fringe of European politics and interests. Studies of religion in this fringe provide, however, a mirror – a new perspective on European values and, prominently, religion. A case in point is Montenegro, a newly founded state with deep historical roots in the 7th century, which is today a continual reminder of how unstable states, governments, nations and, in particular, religious communities continue to be in Europe and the United States. Currently, the Montenegrin state is in the making, and so it offers insights into the crucial factors and mighty forces of humanity that make or break religions and societies – history, memory, ideology and even war. The national and religious identities in Western countries might have seemed more stable than in Montenegro until recently, but places such as Montenegro are a reminder of how swiftly a shift in religious or national identity might come and how deep the consequences can be, as far as political turmoil and war are concerned. In Montenegro, a shift occurred in less than a decade which involved two wars. Today Ukraine has become another horrible example of the same process. It is a reminder of how shift in religious and national affilations is tightly bound to political, economic and military conflicts.

This study is an attempt to look into the structures and reasons behind the shift in Montenegro and relate them to broader South Eastern European and European contexts. The focus is on how a shift in religious and national identity plays out in materials, place-making, ritual performances, historical writings and, finally, theology. In other words, the book examines The Historiographical Practice and Religious Ideology of the Eastern Orthodox Churches in Montenegro and Its Backdrop in Theology.

The question slowly formed in my mind when I first entered South-East Europe as a young scholar in May 2011. I crossed the Montenegrin-Albanian border with a group of researchers under the direction of Professor Jørgen S. Nielsen. Late in the evening, we came to Montenegro. We passed Mount Rumija, the ruins of the city of Suacium. We were accommodated in the old citadel of the House of Balšić. This book reflects my initial interest and ten years of work on the history and historiography of those sites, churches and communities that I saw for the first time back then. It is a history deeply connected to the inner dynamics, emergence and struggles of the Orthodox communities after communism.

Perhaps I had not foreseen that this topic would become relevant so quickly, as the case has been in recent years. In April 2019 the Montenegrin government tried to overtake a central Serbian Orthodox Monastery at Kotor Bay. It was met with fierce Serbian Orthodox Opposition. This incident was the first in an escalating struggle that would change Montenegrin politics. In May 2019, the government proposed a new controversial law on religion, which was passed through parliament on 24 December 2019. This new law brought the Serbian Orthodox Church and its supporters in Montenegro to the streets during the December snow. The confrontation continued into 2020 and even through the pandemic lockdown in the spring. The conflict ended with the general election of 2020 when the government failed to be re-elected for the first time in thirty years. Shortly after this, the main spokesperson of the Serbian Orthodox Church in Montenegro, Metropolitan Amfilohije, died of covid-19, thereby ending his thirty-year tenure. The fall of the thirty-year rule of the former Montenegrin government and the death of the Serbian Metropolitan Amfilohije marked the end of an era in Montenegrin history. An era with which this book is preoccupied. The intense conflict in 2019–2020 was about the right to the history and religious heritage of Montenegro, the very theme of this book. A debate that continued into 2021 and 2022 with its epitomical moment when the roads to the former Montenegrin capital, Cetinje, were blocked in September 2021 by demonstrations that set fire to their “walls” of car decks. The protesters tried to block the installation of a new Serbian Metropolitan in Montenegro to fill Amfilohije’s throne.

A religious and political question is beneath all of this, which arose from the disintegration of Yugoslavia and communism. The same development can be seen throughout South-East Europe. In this book, I will provide an analysis of not only the content of the conflict in Montenegro and its deeper structures but also relate these developments to other countries in the former Yugoslavia, namely Serbia and North Macedonia with an outlook to Bulgaria and Ukraine.

My argument is that there is a deeper religious ideological structure and theological reasoning beneath all of these struggles in the post-communist countries, which form them and provide them with theological foundations. In a sense, these deeper structures of history provide the scene where the national and religious struggles are to be played out. In other words, the struggles would not take place without an already set battle scene. I will try to provide a characterisation of these ideological structures, as they are formed throughout history.

Parts of chapters 2 and 5 have been published as prior articles (Saggau 2018; 2017; 2019a: 2019b: 2017b: 2020a), but they have been reworked, updated and incorporated into the general argument of this book.

Acknowledgement

The work on this book have brought me far and wide in former Yugoslavia. I am very grateful for the help from local scholars, journalists, clergy members and ordinary people. I owe much gratitude to Omer Kajoshaj, Professor Vladimir Bakrač from Montenegro and Professor Mirko Blagojević from Belgrade.

My former advisor, Carsten Selch Jensen, has helped me along the way, providing care in hours of need, offering skilful comments and reassuring me that I was not lost, but on track. Thanks to my colleagues at the University of Copenhagen and other institutions in Cambridge, Erfurft, Belgrade, Vienna, North Macedonia and Montenegro for their openness to me and for all the ongoing discussions and side projects. A special thanks to Sebastian Rimestadt and David Heith-Stade, who frequently and promptly answered my many questions. A final academic thanks to my long-time inspiration and friend, Professor Jørgen S. Nielsen. The project would be unthinkable without him, his early guidance and the vast network in South East Europe, to which I have been fortunate enough to be introduced.

Thanks to Mihai Dragnea, President of the Balkan History Association and Editor-in-Chief of this series and the journal Hiperboreea, who supported the publication of my work. A warm thanks to Philip Dunshea and the team at Peter Lang as well, who – together with four in-depth reviewers – made this book far better than I had imagined it to be.

I have been fortunate to receive enough funds to complete this work. I would like to thank the generous funders from Oscar Andersen’s Foundation, G. C. E. Gad’s Foundation, Jens Nørregaard’s Legate, the Centre for Modern European Studies, ISORECAE’s board for the Miklós Tomka Award, the Council of Churches in Denmark for the Ecumenical Legate as well as the Independent Research Fund Denmark and former Minister of Higher Education and Science, Tommy Ahlers (along with the Crown Princess) for the Elite Research travel stipend.

Thanks to family and friends for their support and appreciation for stories. I have particularly been glad for the company of my father, a historian, during my travels and field site visits in Montenegro. There is no one else I would have preferred as the driver when our car was stuck (twice) in surprisingly thick April snow in the inaccessible Montenegrin mountains, without a map and with a broken GPS shortly after a breakfast rakia. No driver has ever taken the angry sheep across the thorny ruins of Suacium in hail so relaxed. A final thanks to my wife and kids. I hope you will enjoy my work and continue to partake in it – and the travels.

Notes on terminology

In this book, I have not altered the self-identification of identity or language. This approach means that I refer to the Montenegrin language and ethnicity if the source self-identifies as Montenegrin. This practice is not a statement about my own position. I have referred to Njegoš and other proto-national figures with a very generic term “Slavic” rather than call them “Serbian” or “Montenegrin” in order to avoid any embroilment in current debates. This book is not about which “ethnicity” they belong to.

Most translations of quotes are my own if nothing else is stated (from time to time, with help from indigenous speakers). Crucial quotes have the original Serbian or Montenegrin text in brackets after the English translation.

The use of names for clergymen, such as Metropolitan Amfilohije, follow the Orthodox tradition and call them by their monastic names – sometimes with their full name or secular names in brackets. In general, I used the Latinised version of Montenegrin or Serbian names and places. Otherwise, the Latinised English name is given preference. A name on point is Lake Skadar or Kosovo, as they are called in Serbian, which from an Albanian point of view would be translated into English as Lake Skhöder or Kosova. The book is about Serbs and Montenegrins, wherefore the places and names follow their tradition.

Most names use the Latin version of Serbian and Montenegrin with special signs such as “š”, “ž” or “Đ”, or the standard English alliteration whereby Lovćen becomes Lovchen or Đukanović becomes Djukanovich and so on. For Russian, Ukrainian, Bulgarian Orthodox names, etc., I used the English standard version of the name, church or place.

Details

- Pages

- XXII, 220

- Publication Year

- 2024

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781433197420

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433197437

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433197413

- DOI

- 10.3726/b21847

- Open Access

- CC-BY

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2024 (March)

- Keywords

- Eastern Orthodoxy Religion Nationalism Theology Montenegro Serbia Serbian Orthodox Church Yugoslavia Church History Balkan Historiography Nationalisation of the Sacred Orthodox historiography, memory, and politics in Montenegro Emil Hilton Saggau

- Published

- New York, Berlin, Bruxelles, Chennai, Lausanne, Oxford, 2024. XXII, 220 pp., 9 b/w ill., 3 tables.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG