Art, Identity and Cosmopolitanism

William Rothenstein and the British Art World, c.1880–1935

Summary

(Sarah Victoria Turner, Director of the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art)

«In this superbly well-researched book, Samuel Shaw argues convincingly that a commitment to British identity, including the experience of British Jews, is in no way at odds with a cosmopolitan openness to artistic activity across the whole of Europe, Asia and beyond. This will be the standard work on Rothenstein in his time for years to come and required reading for anyone interested in the international artworld of the period.»

(Elizabeth Prettejohn, Professor of History of Art, University of York)

The artist, writer and teacher William Rothenstein (1872–1945) was a significant figure in the British art world of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. He was a conspicuously cosmopolitan character: born to a German-Jewish family in the north of England, he attended art school in Paris, wrote the first English monograph on the Spanish artist Goya, and became a prominent collector and supporter of Indian art. However, Rothenstein’s cosmopolitanism was a complex affair. His relationship with his English, European and Jewish identities was ever-changing, responding to wider shifts on the political and cultural stage. This book traces those changes through the artist’s writings and through his art, analysing a range of paintings, drawings and prints created from the 1890s into the 1930s. This book – the first in-depth study of Rothenstein’s art – draws on extensive archival material to situate his practice within broader debates regarding transnational exchange and the development of modern art in Britain.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Yorkshire, 1872–1935

- Chapter 2 Continental Europe, 1889–1914

- Chapter 3 London, 1895–1910

- Chapter 4 Asia, 1890–1930

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

Illustrations

Effort has been made to include within this study a range of images, with priority given to those discussed at length within the text. There are many images, however, that could not be included. Some of these can be found online, in specific museum databases, or databases such as Art UK. I encourage readers to make use of these websites to refer to images that are not printed here. N.B. Measurements for works listed below can be found in the image captions.

Acknowledgements

During the ten or so years I have been working on this book I have lived in four different cities on two different continents, taught in seven universities, and given talks at various conferences and events. On this basis the list of people who have contributed to the development of the book should be much longer than the one below. If anyone reading this thinks they should have been included, they are probably right.

Thanks, first, to the extended Rothenstein family for responding to many queries over the years and for being so generous with their time: especially Lucy Carter, David Ward, Richard Spiegelberg and Max Rutherston.

Thanks to Bradford Museums and Galleries, Jill Iredale in particular, for organising the 2015 exhibition From Bradford to Benares: The Art of Sir William Rothenstein, and to Rachel Dickson and Sarah MacDougall for organising the related exhibition, Rothenstein’s Relevance: William Rothenstein and His Circle at the Ben Uri in London in 2016.

Thanks to the Yale Center for British Art (The Prints & Drawings department especially) where I spent three happy years between 2013 and 2016, and to the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art for awarding me a postdoctoral fellowship back in 2012, when I started writing this book.

Thanks to the following museums and archives for their assistance along the way: The Houghton Library at Harvard (home of the Rothenstein archives), Manchester City Art Galleries, Bradford local archives, Tate and Tate Archives, Boston Museum of Fine Arts, The Jewish Museum in New York, and the Leeds Jewish Historical Society.

Thanks to the Universities of York, Warwick, Yale, Sussex, Birmingham, and Leicester, and to all the students I have taught there – and who have taught me so much in return. The latter institution deserves special thanks for continuing to grant me library access during the months of the pandemic. Thanks also to The Open University, my current employer, for helping with image fees. I am very lucky to have landed in such a supportive and friendly History of Art department.

For academic support and discussion, thanks (in alphabetical order) to:

Tim Barringer, Jonathan Black, Kristin Bluemel, Grace Brockington, Martin Brook, Naomi Carle, Emma Chambers, Meaghan Clark, David Peters Corbett, Sasha Dovzhyk, Alice Eden, Jason Edwards, Jessica Feather, Pamela Fletcher, Gillian Forrester, Rowena Fowler, Bashabi Fraser, Andrew Glazzard, Mark Hallett, Sophie Hatchwell, Michael Hatt, David Boyd Haycock, Anne Helmreich, Ysanne Holt, Claire Jones, Mark Samuels Lasner, Hana Leaper, David Frazer Lewis, Charles Martindale, Kenneth McConkey, Kate Nichols, Barbara Pezzini, Elizabeth Prettejohn, Anna Gruetzner Robins, William Rough, Michael Seeney, Frances Spalding, Andrew Stephenson, Margaret Stetz, Robert Sutton, Sarah Victoria Turner, Michael White, Lesley Wylie, and Harry Wood.

Thanks to my family: Mum & Dad, Ruth & Jim, Ed, Pippa & Pete, Simon & Zoe, Walter, Ada & Sarah.

Abbreviations

All references to ‘Houghton Library, Harvard’ are to the archive ‘Sir William Rothenstein correspondence and other papers, call no: MS Eng 1148’ held at the Houghton Library in Harvard. A full collection inventory can be found at the following web address: <https://hollisarchives.lib.harvard.edu/repositories/24/resources/1734/collection_organization> accessed 9 January 2023. At the time of writing, some portions of the archive have been digitised; all my quotations from the archive were transcribed between 2008 and 2016. Where letters were undated, I have provided an estimate in brackets.

Introduction

In the summer of 1904, Bradford’s Cartwright Hall Gallery opened with an ambitious survey exhibition tracing ‘the development of English Art from Hogarth down to our own time’.1 Despite its nationalistic tone, ‘English Art’ – as visitors may have noted – was something of a misnomer, for not only did the exhibition include many artists from Scotland, Wales and Ireland but, in many cases, much further afield.2 Peter Paul Rubens was included, for instance, owing to his Virgin and Child (probably a copy) having been owned by local industrialist Samuel Lister, who financed the gallery. It was in the selection of contemporary art, however, that the organisers took a notably generous understanding of ‘Englishness’ – or, at least, it was here that the cosmopolitanism of English art was made most evident. Here you could find the work of several American-born artists, since settled in England, including James McNeill Whistler (who had died the previous year), John Singer Sargent, Henry Muhrman, and Mark Fisher. There were two French-born artists represented: Alphonse Legros, who had become a naturalised British citizen in 1881, and Lucien Pissarro, son of Camille, who would not gain citizenship until 1916. Among the leading young artists, meanwhile, Walter Sickert was born in Munich (to a Danish-German father and English mother) and Charles Ricketts in Geneva (to a French mother and English father), while Charles Conder, though born in Middlesex, was very much a product of the wider Empire, having spent his childhood in India and Australia. All three of these artists produced work that was, in different ways, heavily indebted to non-English precedents.

There were also foreign subjects aplenty, including landscapes of Italy by J. M. W. Turner and Richard Wilson, scenes of Dieppe painted by William Nicholson and D. S. MacColl, and drawings by Legros, the titles of which (naturalised citizen or not) were all presented in his native tongue. German subjects were sprinkled throughout the exhibition, including two or three works by an artist named ‘W. Rothenstein’, who offered two landscapes from Hildesheim, a town outside Hanover, and a painting called Flower, Fruit & Thorn Piece, which referenced the German writer Jean Paul. Rothenstein also exhibited a couple of Burgundian subjects, and lithographic portraits of Auguste Rodin, Henri Fantin-Latour, Adolph Brodsky, and Adolf von Menzel. Those who cared to look more closely at this seemingly cosmopolitan character would discover that he was also associated with Spanish art, in particular the artist Goya, on whom he had recently published the first monograph written in English, a text that opened with rather disparaging comments about the English tradition.3 Rothenstein was one of the best-represented contemporary artists in this survey of ‘English’ art – but how English was he?

Rothenstein as a cosmopolitan artist

‘… the thoughts of a thinker and the mots of a wit who couldn’t have seemed more at home on his own shores – whatever those shores might be’

– Max Beerbohm on William Rothenstein (1926)4

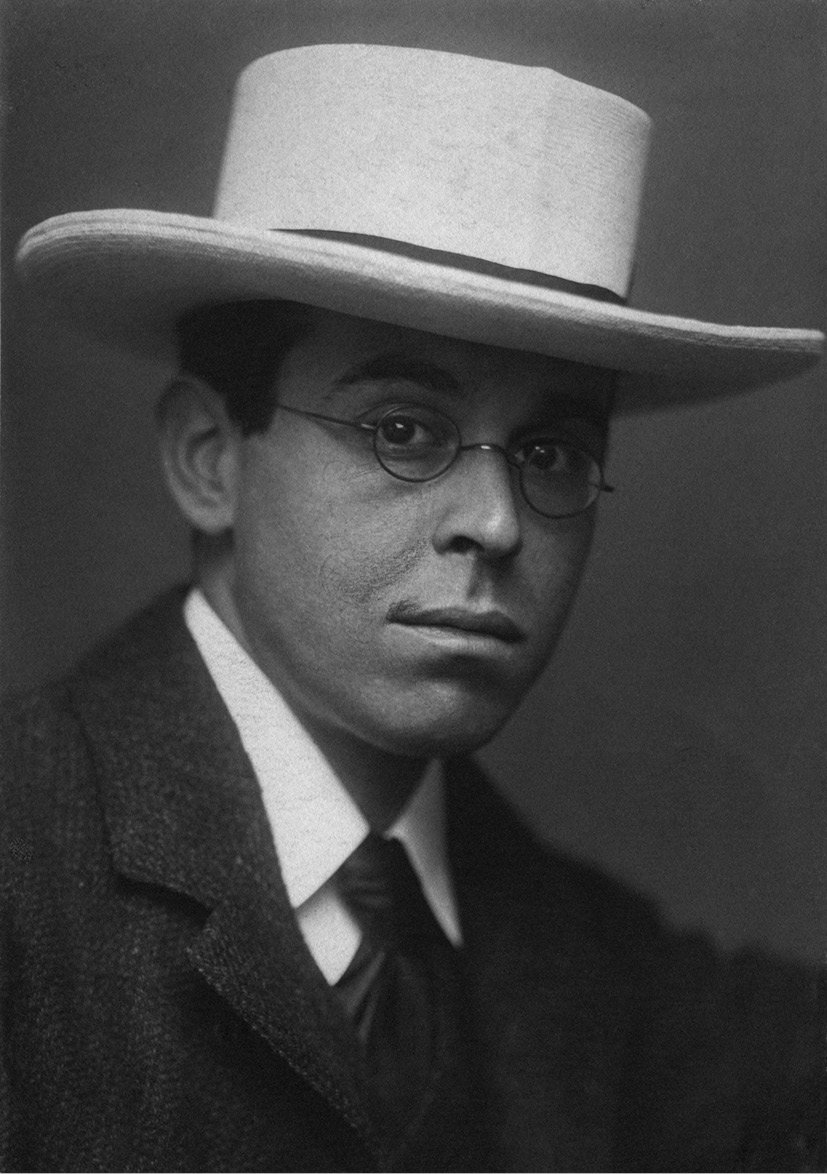

As his friend Max Beerbohm would later note, William Rothenstein (Figure 1) was widely perceived at the turn of the century not as a securely English artist, but a man of many, or uncertain, ‘shores’: an artist who belonged everywhere and, perhaps, nowhere.5 Beerbohm would elsewhere refer to Rothenstein as a ‘Japanese jew [sic] with a Franco-German accent’, adding ‘He was foreign’.6 Although the opening designation was probably intended to mock Rothenstein’s short stature, the inclusion of an Asian inflection to an already heady European mix was not entirely anachronistic. Rothenstein, like many of his generation, was not only a keen collector of Japanese art but came to be one of the leading proselytisers of Indian art in Britain. During the First World War rumours circulated that Rothenstein, now an Official War Artist (an appointment that seemingly sealed his English allegiances), had turned up at the front line in France orating in Hindustani.7 No one who had followed his career during the previous four years would have been surprised. Following his 1910–1911 trip to India, Rothenstein had been turning out many drawings and paintings on Indian subjects. In 1911 he expanded his range of non-western themes to include a portrait of two Peruvian boys, Omarino and Ricudo, who had been brought back from South America by the Irish writer Roger Casement.8 During his time as a war artist he made a special study of Indian troops and, in the 1920s, contributed a large painting on an Indian subject for the interior of the Palaces of Westminster.9 On top of this he was also, as Beerbohm noted, Jewish: a fact that had little discernible effect on the subject matter of his art in his early career, only to become a key feature of his artistic identity in the 1900s, as I explore in Chapter 3.

Figure 1.George Charles Beresford, William Rothenstein, platinum print, c.1902 © National Portrait Gallery, London

Rothenstein’s cosmopolitanism, often noted during his lifetime, has continued to attract attention from scholars. His connections with India, Germany and France, and to a lesser extent his Jewish roots, have been widely discussed and it is generally taken for granted that he was, as Anne Helmreich has argued, a ‘critical catalyst’ for ‘cosmopolitanism in the Edwardian art world’, a figure who adopted and encouraged ‘internationalizing strategies’.10 In Towards the Sun: The Artist-Traveller at the Turn of the Twentieth Century, Kenneth McConkey’s recent study of British artists working abroad at the turn of the century, Rothenstein is a recurring figure, appearing in chapters on France, Spain and India.11 There seems to be no doubt that he was a cosmopolitan artist. But what forms did his cosmopolitanism take?

While building upon Helmreich and McConkey’s arguments, which rightly challenge traditional notions of an insular turn-of-the-century British art scene, this book also demands that concentration on Rothenstein’s international connections is balanced by an understanding of his simultaneous allegiances to the country and county of his birth. After all, despite the distinctly cosmopolitan flavour of his exhibits at the 1904 Bradford Exhibition, Rothenstein was not only taking a key role in a survey of English art, but one staged in his hometown. He appeared at Bradford both as a man of the world, but also the most local of the artists to exhibit there. He and his brother Albert – who also contributed to the exhibition – had been born just down the road, off Manningham Lane. Their father Moritz, born in Germany, was by 1904 a respected Bradford businessman, and a committed Anglophile.12 The Rothenstein family not only thought of themselves as part of the English art scene, but believed in the category of English art, even while they sought to disrupt such clear-cut national boundaries. To be cosmopolitan, after all, is not to deny borders, or even to despise them, but to retain the right to cross them. As the philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah has noted: ‘I don’t think that cosmopolitanism has to be either elitist or unpatriotic; I think it’s perfectly possible to combine a sense of real responsibility for other human beings as human beings with a deeper sense of commitment to a political community.’13 That is to say, you can believe in common ground, in internationally shared ideals and characteristics, while holding on to national and/or local accents. As Appiah writes elsewhere (in relation to the concept of ‘rooted cosmopolitanism’): ‘the cosmopolitan believes […] that sometimes it is the differences we bring to the table that make it rewarding to interact at all’.14 This book underlines the importance of these ideas to Rothenstein’s practice.

Given that cosmopolitanism always was, and remains, a ‘contested concept that generated debate and disagreement’, we should not be surprised to find apparent contradictions within the outlook and practices of so-called cosmopolitan artists.15 As Mark A. Cheetham has argued, ‘cosmopolitanism is forever fraught with contradictions, not least because it abuts other complex ideas such as the global, the nation, the post-colonial, hybridity, diaspora and multiculturalism’.16 Rothenstein deserves to be described as cosmopolitan; however, we also need to take seriously his son’s countering claims (based on a narrower reading of the term than that proposed by Appiah) that his father had an ‘innate antipathy for cosmopolitanism’.17 This book accepts the possibility that these two designations may and can co-exist in the career of a single artist, and seeks to explain why.

An English interior?

There were moments when Rothenstein seemed to not only stamp his ‘Englishness’ upon a canvas, but hint at his desire for middle-class respectability. Rothenstein’s 1900 painting, The Browning Readers (Bradford Museums and Galleries, Figure 2), one of the paintings exhibited at Bradford in 1904, is frequently brought forward as an example here – and is an image to which I will frequently return in this book.

Figure 2.William Rothenstein, The Browning Readers, oil on canvas, 1900 (76 × 95.6 cm) © Bradford Museums & Galleries / Bridgeman Images

The artist’s wife Alice sits reading on a wicker chair in the front room of their Kensington cottage, while her sister Grace selects a volume of Robert Browning’s work from a bookshelf.18 Scholars have written of the painting’s ‘intrinsic’ or ‘essential’ Englishness, invoked by the allusion to Browning, and the Pre-Raphaelite mood of the women’s dress, with its echoes of John Everett Millais’s 1851 painting Mariana.19 But there are other things going on here, including references to James McNeill Whistler (‘Symphony in Green and White’ would serve well as an alternative title), to seventeenth-century Dutch interiors, and to the French muralist Pierre Puvis de Chavannes.20 There is blue-and-white porcelain on the cabinet below the bookshelf, while the mantelpiece boasts a Chinese porcelain Guanyin and a small Egyptian cat. The sprig of blossom on the mantelpiece recalls Japanese ukiyo-e. The framed works on the wall are unidentifiable, though there is a good chance that they, too, are not English: Rothenstein owned drawings by Rembrandt and Hokusai, among others. On the top shelf, above the collected edition of Browning, are a group of books with yellow spines, a colour usually associated with modern French literature.21

The Browning Readers exemplifies a man keen to cast his artistic net wide; a man who wants viewers to know that he is as familiar with Browning as he is with foreign ceramics; who sees far beyond national boundaries when fashioning artistic statements. The interior may initially strike us as ‘English’, but the painting is clearly part of a wider international tradition of domestic interiors, discussed further in Chapter 3 of this book, which includes the work of Pierre Bonnard and Edouard Vuillard in France (who trained, like Rothenstein, at the Académie Julian in Paris), Vilhelm Hammershøi in Denmark, and the Boston School in the United States, especially the work of Edmund Tarbell. It also recalls Henri Matisse’s 1895 painting Woman Reading, which Rothenstein may have seen at the 1896 Salon Champ-de-Mars.

The Browning Readers, despite its appearance of middle-class respectability, came hot on the heels of another interior, The Doll’s House (1899–1900, Tate, Figure 15) in which the artist represented his wife in a claustrophobic French interior, with a title adapted from Henrik Ibsen’s controversial play of 1879.22 Exhibited at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1900, in the British Section at the Grand Palais, The Doll’s House was awarded a silver medal. This distinctly European painting could probably have hung in any of the national sections of the Exposition; this did not stop the British from taking credit for its achievements. It would later be donated to the Tate by Rothenstein’s brother Charles, to form part of the narrative of modern art in Britain – a role it continues to play today.23 The Browning Readers and The Doll’s House form an uneasy yet illuminating duo, to which I will return in Chapter 3.

As recent studies have convincingly shown, these paradoxes were by no means untypical of the period, in which nationalistic sentiments often intermingled with the increasing cosmopolitanism of the European art world.24 The push and pull of cosmopolitanism and nationalism is a relatively old story in the history of modern European art. The ‘interplay of insular and outward-looking aspects in Hogarth’s art and thought’ was, for instance, the central theme of a recent exhibition at Tate Britain.25 Matthew Craske, meanwhile, writing about eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century Europe, notes that ‘the world of the Grand Tour was typically riven by tensions between the ideal of cosmopolitanism and the practice of national prejudice’.26 It is nonetheless fair to say that in the late nineteenth century these tensions were amplified, both generally and in the careers of specific artists. This is seen most clearly in the case of the International Exhibitions (or Expositions), such as the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1900, which encouraged and celebrated exchange while stoking competition.27 Internationalism consistently demanded its antithesis: the constant underlining of national boundaries.28 It suited many artists to play both games: to embrace the spirit of pre-war transnational exchange, while securing their position within the framework of national schools. There were sound practical reasons for this. National schools helped make sense of a complex and crowded market, offering a loose brand identity based on geography and some shared cultural and social characteristics. The expansion of European empires also played into this tension between the national and the international; the empire both facilitating knowledge of distant cultures, while claiming them as part of the European nation. India, in this way, could be both Britain and other.29

In this sense, William Rothenstein’s experiences were not remotely unique. The European art world was (and had long been) full of cosmopolitan characters, willing to fly the national colours when required. This was exemplified by the artist’s society to which Rothenstein belonged in his early career: The New English Art Club, the name of which sounds fiercely patriotic, but whose members were united by their appreciation for contemporary French art. Indeed, many members of the New English Art Club were also members of the International Society of Sculptors, Painters and Gravers (my italics), founded in 1898.30 To speak of the national versus the inter- or transnational is, therefore, to oversimplify: the choice was rarely so stark. Even those who openly embraced cosmopolitanism – and Rothenstein was certainly one of these – understood that engagement with other cultures was a complex, even risky, process.

Details

- Pages

- XVI, 366

- Publication Year

- 2024

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781800792128

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781800792135

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781800792142

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781800792111

- DOI

- 10.3726/b18017

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2024 (February)

- Keywords

- cosmopolitanism cultural identity transnationalism and the arts William Rothenstein British art German-Jewish artists

- Published

- Oxford, Berlin, Bruxelles, Chennai, Lausanne, New York, 2024. XVI, 366 pp., 7 fig. col., 27 fig. b/w.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG