Communication and Politics in the Hispanic Monarchy

Managing Times of Emergency

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

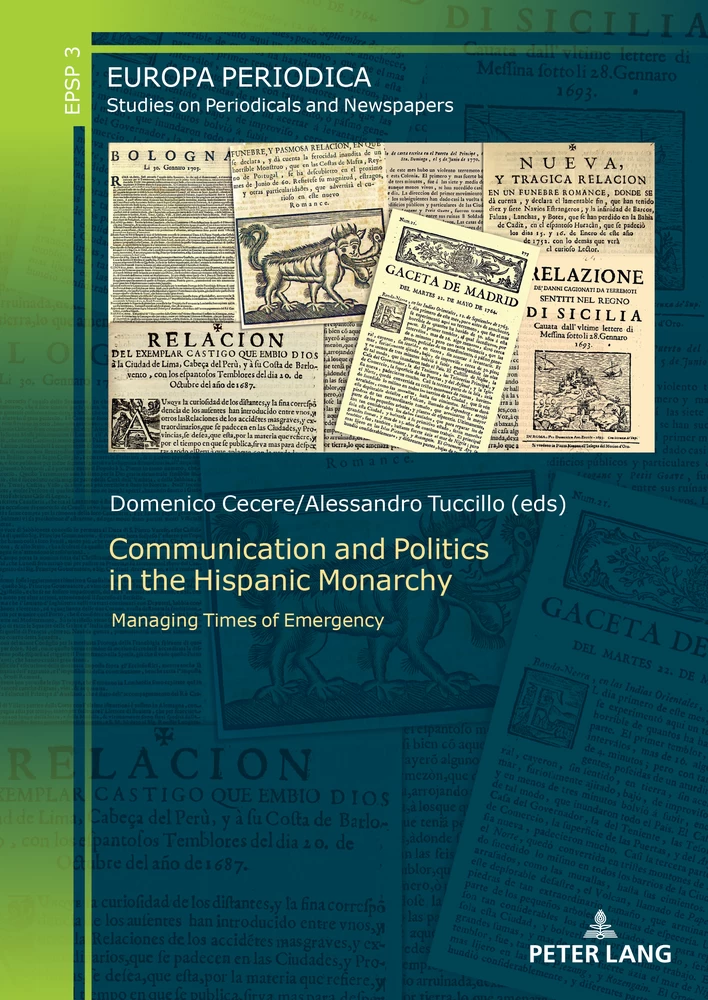

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Acknowledgement

- Times of emergency: Managing communication and politics in the aftermath of a disaster

- Section I: Controlling the flow of news

- Early modern information: Collecting and knowing in Spain and its Empire

- Calamities, communication and public space between manuscript and print (Spain and Portugal, sixteenth and seventeenth centuries): From prayers to news

- Decide, apply and communicate: The colonial administration in Mexico faced with extreme weather episodes

- Section II: From relaciones to periodicals

- A linguistic perspective on the reporting of seventeenth-century natural disasters

- The rhetoric of disaster between the pre-periodical and the periodical press: The Guadalmedina flood (1661) and the case of the Gazeta Nueva

- Communicative strategies in relazioni on the 1669 eruption of Mount Etna

- Countering the spread of contagion. Plague and the media: A close relationship, the case of Conversano (1690–1692)

- A comparative analysis of earthquakes as reported in the official Spanish press (1770–9): A commercial strategy?

- Section III: The logistics of communication

- Crisis as a measure of communicative capacity in the Spanish Empire: Letters, messengers and news informing Spain of the Sangley uprising in Manila (1603–1608)

- The 1645 Manila earthquake: The distance-time problem during emergencies

- Standing on shaky ground: The politics of disasters in early modern Peru

- Mechanisms and strategies for communication in time of war during the eighteenth century

- Section IV: Putting a spin on disasters

- Divine intervention? The politics of interpreting disasters

- Disaster and personal perception: The Calabria and Messina earthquakes (1783) according to the account by the Spanish clergyman Antonio Despuig y Dameto

- Between the brilliant light and the shadow of the insects: The instruction on the plague of locusts ordered by the Government of Guatemala in 1804

- Index

Acknowledgement

The papers collected in this volume stem from a range of seminars and workshops held in 2018–2021 as part of the DisComPoSE research project (Disasters, Communication and Politics in Southwestern Europe. The Making of Emergency Response Policies in the Early Modern Age). Many were presented at the Comunicazione, politica e gestione dell’emergenza nella Monarchia ispanica, secoli XVI–XVIII conference held online on 7–8 June 2021. Our gratitude goes to all of the members of the DisComPoSE research group and the many colleagues who contributed in various ways on several different occasions as this volume was being prepared, and in particular to Giancarlo Alfano, Beatriz Álvarez García, Antonio Álvarez-Ossorio Alvariño, Yasmina R. Ben Yessef Garfia, Davide Boerio, Diego Carnevale, Massimo Cattaneo, Vittorio Celotto, Chiara De Caprio, Giulia Delogu, Patrizia Delpiano, Filippo de Vivo, Valeria Enea, Carmen Espejo-Cala, Valentina Favarò, Idamaria Fusco, Adrián García Torres, Manuel Herrero Sánchez, Paulina Machuca, Giuseppe Marcocci, Ida Mauro, Francesco Montuori, Giovanni Muto, Elisa Novi Chavarria, Pasquale Palmieri, Rosa Anna Paradiso, María Eugenia Petit-Breuilh Sepúlveda, Massimo Rospocher, Gennaro Schiano, Umberto Signori, Gennaro Varriale, Piero Ventura and Milena Viceconte. Finally, we would like to extend our most heartfelt thanks to Anna Maria Rao for her constant encouragement and inspiring guidance, and to Manuela Pitterà for her invaluable support.

Domenico Cecere and Alessandro Tuccillo

Times of emergency: Managing communication and politics in the aftermath of a disaster*

1. Fate presto

Fate presto [make haste] was the headline of the Naples daily Il Mattino on 26 November 1980, three days after the earthquake that devastated Irpinia and Basilicata. The headline conveys the gravity of a disaster that killed almost 3,000 people, injured about 9,000 more and left 400,000 without a roof over their heads. It is emblematic of the role that certain channels of information took on in a crisis, summoning the authorities to swift and effective action in the areas affected to rescue those trapped under the rubble and alleviate the suffering of those who had survived. This was not just a generic call to action. It called out the inadequate response that was aggravating the situation, as government bodies and national information channels had initially tended to underestimate the scale and impact of the earthquake. Rescue efforts had been tardy and the measures deployed were not up to the task. Indeed, over the years, the sluggishness and incompetence of the authorities have featured prominently in public criticism of how the emergency was handled. The inadequate response to some extent shaped how the measures deployed in Irpinia were judged, given the overwhelming delay and inefficiency in how reconstruction funds were managed, as well as the corruption and the meddling of organised crime, both well documented1.

Also on 26 November, Italy’s head of state, President Sandro Pertini, harshly criticised the handling of the disaster, issuing a heartfelt appeal for immediate assistance to be provided to the victims. The headline on the front page of the Naples daily went straight to the heart of what needed to be done. Fate presto and the sub-headline Per salvare chi è ancora vivo, per aiutare chi non ha più nulla [to rescue those left alive, to assist those left with nothing] raised public awareness domestically and internationally about the emergency, encouraging individuals and organisations to volunteer their services and accelerating the provision of assistance from surrounding areas, from other parts of Italy and from abroad2.

A more recent disaster disaster has revealed other aspects of the essential yet problematic role of communication in times of emergency. The earthquake that struck L’Aquila and parts of Abruzzo on 6 April 2009 received notable attention internationally not only because of the 309 fatalities and the destruction of several residential areas, but also because of the decision taken by then premier Silvio Berlusconi to host a G8 meeting in L’Aquila. The communicative impact of this decision served many purposes, most of which were related to domestic politics. However, the international reverberations of the L’Aquila earthquake over the following months and years were fuelled not only by the decision of a head of government who was also a communications entrepreneur, but also by the subsequent trial of the members of the Commissione Nazionale per la Previsione e Prevenzione dei Grandi Rischi [National Committee for the Forecasting and Prevention of Significant Dangers]. The scientists and officials on the committee were accused of providing, just a few days before the earthquake struck, misleading and contradictory information about the likelihood of a powerful earthquake and about what precautions should be taken, if any. The frequent minor tremors felt over the preceding weeks had generated extensive public debate in the local and national press, with contributions from local mayors, government officials, members of authoritative scientific institutes, experts expressing their personal opinions and so on. The communications landscape became crowded and noisy, polarising public opinion into an alarmist camp and an unconcerned camp. Following the disaster of 6 April, media pressure shifted the debate to understanding the causes of the disaster and to ascribing responsibility so that guilty parties could be identified3.

These observations on the 1980 and 2009 earthquakes illustrate some of the main communicative, societal and political dynamics that emerge when modern-day societies are hit by a disaster with natural causes, or when disasters of this kind threaten. The volume of information and images disseminated, and the speed with which they spread, depends on the available communications technology. The extraordinary tragic news swiftly reaches a broad public, often at some distance from the epicentre. The media will swoop on almost any news whose sensationally catastrophic nature makes it fit to print as they compete to shape public opinion, which is nowadays forced to come to terms swiftly with other people’s grief. There is no time to fully assimilate the information as the next news item is already grabbing the public’s attention4.

On the other hand, the potentially global coverage that events of this kind receive in the mass media, at least initially, bestows great power on the communication of disasters. How the information is gathered, elaborated and transmitted influences governments in the decisions they make about how to handle emergencies5.

Accounts of disasters also reveal many other related issues, providing food for thought about the central role of information in times of emergency, in particular about the role of periodicals and the complex relationship between communication and the perception of risk. An important aspect of understanding how disasters, whether environmental, biological or anthropic, are framed in mass communication is the raised tolerance threshold of contemporary society. Unlike earlier societies, contemporary societies see themselves as taking a calculated approach to anticipated risk6, as being able to elaborate knowledge and apply technologies to prevent risks or mitigate their effects, often based on a precautionary principle expressed as laws, prescriptions or procedures. It goes without saying that assuming that an acceptable risk threshold can be defined objectively and that neutral parameters can be defined to guarantee public safety comes up against the issue of whether risk is in fact a social construct, on which there has been substantial consensus in the social sciences over recent decades7. Risk is not simply an intrinsic property of natural phenomena or a physical property of the environment, but is also the result of collective subjective perception and assessment. It cannot therefore be ascribed to a theory of rational choice, but can only be understood relative to the social and moral norms of the specific societies concerned, and the technological capacities of these societies. Individuals, groups and societies are selective in their approach to threats, defining hierarchies of risk not only on the basis of the available technology to identify and monitor risks, but also on the basis of prevailing value systems and power relationships within societies. The dynamics of communication are central to the processes of the selection, prioritisation and social perception of risk. The tolerance levels of threats to public safety are therefore determined by those who wield the power to gather and manage information.

These considerations reveal the difficult and potentially conflictual nature of the relationship between science, communications and politics in times of emergency. They also shed light on another issue. In the past, the causes of disasters were sought outside societies – in the stars, in divine plans, in the actions of fringe groups and so on. Today, the causes tend to be sought within societies8. The desire to control nature and therefore mitigate any risk leads to seeking the causes of these tragedies in errors, failings, omissions, underestimations and so on, whether real or presumed. The role of the mass media is once again crucial to attributing responsibility, as it can meet society’s expectation that it can identify errors or omissions. Laying blame immediately and definitively, on a scapegoat if necessary, is a characteristic of many media narratives in the face of imminent risk or in the aftermath of a catastrophe.

2. Communicating disasters

The scale of the political import of information is made even clearer by the rapid and disruptive developments in communications technology in the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. These developments have led to the almost global reach of media networks, as well as transmission speeds that provide news almost in real time and ever-increasing access to news thanks to the all-pervasive proliferation of devices that can deliver it.

Nevertheless, communications in times of emergency were no less important even before these game-changing developments. Communicating emergencies has always been a delicate and problematic matter. As noted by Luc Boltanski, the introduction of pity into politics and the spectator’s dilemma are not some automatic consequences of modern media9. Boltanski points out that some of the processes that introduced these elements emerged in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in Western societies and the large areas of the world they dominated. As the early modern period was drawing to a close, the development of pamphlets, novels and literary criticism introduced a range of new topics and three in particular, which he terms ‘the topic of denunciation’, ‘the topic of sentiment’ and ‘the aesthetic topic’. Changes in how individual and collective suffering was portrayed publicly in the second half of the eighteenth century significantly altered sensitivities and therefore mores, and transformed the politics of contemporary societies.

Whether or not one agrees with Boltanski’s account of these sociocultural processes and their periodisation, it is clear that some of the significant changes in the political agendas of governments are not simply a consequence of the evolution of information technology. Indeed, they are above all due to changes in the reporting of the impact of wars, disasters and other collective traumas affecting larger or smaller groups of people. They can also be attributed to the authorities beginning to recognise, from the second half of the eighteenth century, that they needed to demonstrate solidarity with the victims of disasters. This new sensitivity meant that it became the norm for authorities to take victims into account as a matter of course, thus highlighting the political nature of public measures in the face of emergencies10.

This phase, usually seen as the incubation phase or first emergence of these sociocultural processes, is the terminus ad quem of this volume, which brings together methodological considerations and interpretative analyses based on case studies of the vast and diverse political and cultural stage of the territories that constituted the Hispanic Monarchy from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries. Research into the politics of communication in the early modern period and the contemporary period, and into the cultural history of catastrophes, suggests that the analysis of these phenomena can be extended to much broader timescales. There is general recognition of the fundamental importance of research into the emergence in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries of a public opinion that was informed by a press that was less constrained by censorship and could reach an increasingly literate audience. However, communication dynamics of this kind in fact emerged around the start of the seventeenth century or even earlier, albeit limited to a narrower audience. A vast amount of printed and manuscript literature (avvisi, reports, relaciones, short accounts in prose and in verse) contributed to the growth of information networks that needed to satisfy the requirements of a direct and indirect readership keen to know what was happening not only in their own cities and areas but also in foreign countries and the remotest parts of the globe. These decades also saw the emergence and proliferation of periodicals, which in time changed not only how news was elaborated and transmitted but also reading habits in general. Periodicals did not take off easily. In some areas, like the Iberian Peninsula and other Hispanic Monarchy territories, initial experiments were a failure, and it was only many decades later that periodicals as such started to appear at regular intervals. Nonetheless, they fostered the news habit in their readership: ‘great events would still unleash a storm of pamphlets, full of engaged advocacy, but in quieter times readers came to value the steady miscellany of information that arrived with the newspaper’11.

The papers in this volume examine, from a range of different perspectives, the communication strategies of ancien régime societies during emergencies caused by environmental, climatic and biological events, as well as by wars and social unrest, including how such events were reported and explained, and how communications influenced responses to the emergencies. The decision to lump together crises caused by natural events and those created by human beings, like wars or rebellions, may at first glance appear questionable. In fact, maintaining a clear distinction between disasters that have environmental, biological or political causes is a difficult task12. It is abundantly clear that events commonly labelled ‘natural disasters’ in fact have a distinct socio-cultural dimension. Moreover, crises with very different causes can create emergencies with comparable socio-political scope, and their consequences for communication can also be very similar.

The idea of focusing on communication is based on the need to link representations with social and official responses. This requires an interdisciplinary approach that covers textual critique, stylistic and linguistic analysis, and the socio-political history of the organs of government. It is also based on the fact that emergencies triggered by extraordinary tragic events generated a widespread demand for information and the sharing of experiences and opinions in preindustrial societies, albeit not on the same scale as today, and in different forms.

This observation is supported by empirical data and by research in various fields on recent and less recent cases, despite what common sense might suggest. It could be claimed that calamities disrupt communication and weaken social interaction, increasing taciturnity and isolation13. In addition, calamities damage or even destroy infrastructure, leaving individuals bewildered, confused and uncommunicative, and they disrupt the network of relationships that people depend on, forcing them to focus instead on ensuring their own survival. Nevertheless, research shows that social interaction is in fact reinforced after a disaster. Those who survive feel a need to share their experience and their memories. The act of recounting itself, gathering information and comparing one’s memories with those of others, is one of the main ways in which individuals respond to shock. In addition, collective activities like commemorations and scientific or legal investigations help to rebuild the social relationships that were disrupted14.

This does not mean that communication undergoes no changes during and after a calamity. How communities respond to an unexpected threat depends on a series of relatively complex processes: cognitive at the level of the individual, and communicative, social and political at an interpersonal level. These range from how the threat is perceived to elaborating information and taking decisions, processes that require time and need to follow certain procedures. Time is short when emergencies strike, and elaborating strategies or following procedures becomes more difficult, so these processes unfold differently than under normal circumstances. It would, however, be simplistic to suggest that responses and actions are necessarily determined by the panic caused by the unfathomable chaos.

There is a widespread view that disasters swiftly lead to mass panic. In the first half of the twentieth century, this position was advanced by the irrationalist school of crowd psychology, based on the assumption that, when individuals are massed together, emotions overwhelm rational thinking, emulation gets the better of discernment or compliance with norms, and selfish behaviour prevails. A cursory perusal of a large part of the accounts of the disasters of the early modern period supports this view, in particular in narrative accounts written shortly after the event. These accounts often emphasise the emotional response of the people directly affected, describing their overwhelming anguish, panic and irrational fear. The anguish and the fear are only alleviated by prayer, processions and other collective acts of penance.

It is clear that these descriptions are partial, distorted and based on the impressions and preconceptions of those who wrote them. To address these issues appropriately, we would have to shift to the slippery ground of the neurobiology of decision making in individuals beset by uncertainty, which is beyond the scope of this volume and our expertise. However, research has shown that mass panic occurs only under certain conditions, is short-lived and affects only a minority of those present. In fact, detailed analysis of how people behave in the face of danger paints a picture that diverges from the accepted view. While some may act selfishly, most behave in an orderly manner, comply with social norms and tend to help one another. Most researchers agree that experiencing a shared disaster or threat can induce a sense of community, enhanced cooperation and mutual support15. In most cases, the initial disorientation is swiftly followed by a return to social interaction, and coordinated activity is restored after a relatively brief period of fragmentation.

However, re-establishing social cohesion does not always mean a return to how things were before. Emergencies are disruptive, at least in the short term, which reinforces the preconceptions of many observers about the disorder and the chaos. Emergencies create informal communication networks that are very different from those that operate under normal circumstances16. Similarly, decision making also works differently. Decisions are made on the basis of rapidly gathered information that is often incomplete, fragmentary, poorly elaborated and sometimes contradictory. There is a focus on a few salient pieces of information and less important ones are disregarded, with preference given to what appears to be more useful and reliable. Indeed, emergencies often produce too much information. In short, emergencies modify or reshape information networks and how communication is effected, disrupting some channels and creating new ones, or activating new nodes.

At the same time, gathering and reformulating information is even more valuable in times of emergency than in normal times. Information and authoritative opinions allow the authorities to formulate and deploy appropriate political and practical short-term and long-term responses. Moreover, who controls information has the power to validate descriptions and interpretations of events, and thus to shape the assessment of the effectiveness of decisions made about how an emergency was managed, which highlights the political nature of controlling information.

3. The dynamics of news flow in early modern societies

Over recent decades, historiography, working in close collaboration with the social sciences, has significantly augmented and innovated the methodology of research into communication. Narrative texts are no longer seen just as a source of information but have themselves become the object of research. Historians are no longer interested only in the messages conveyed in gazettes, occasionnels, official despatches and private letters, but also in how these are delivered and who the various people involved in producing them are17. Moreover, the media are no longer simply seen as virtual mirrors on reality, but rather as an integral factor in how social reality is constructed18.

The social history of reading and information has been based on models elaborated in the sociology of communication and in semiology. This has sharpened the focus on the social and psychological aspects of the recipients of the texts, on their perceptions and on their liberal interpretations. Historians have stepped away from the traditional notion of communication as a linear process of transferring information and opinions from an official or authoritative source to a passive audience, placing increasing importance on the agency of the recipient and on a range of subjective social, psychological and cognitive variables, and on contextual factors that may influence a response. In the first place, consideration is given to the complex nature of the landscape of communication, where the influence of the many parties involved cannot be assumed in a perfunctory fashion. Moreover, awareness of frequent interference, of mismatched codes and of the central role of personal relationships has led historians to see communication as a bidirectional process of senders and recipients negotiating the meanings derived from interpretations of messages that may or may not coincide with what the sender had anticipated or hoped for.

The questions thrown up by relatively recent emergencies and the evidence provided by research into the resulting social and communicative dynamics also suggest fruitful lines of research into the societies of the early modern period, in particular in the territories dominated by the Hispanic Monarchy. Applying the interpretative methods used in the study of contemporary societies to early-modern societies must, however, be validated against their primary characteristics to avoid falling into the twofold trap of assuming that their social dynamics were either totally different or fairly similar to our own. A range of different characteristics need to be considered, including a society’s avidity for sensational news, people’s need to share the dramatic events they went through and to find explanations for them, a tendency for the authorities and dominant social forces to provide subjective accounts shaped by their own views, different social and political actors competing to find ways to promote their own interests and so on. Dynamics of this kind are not exclusive to modern mass societies but have long been part of the history of humanity. They are very evident in the period from the end of the sixteenth century to the start of the nineteenth century19, which covers the case studies analysed in this volume.

Nevertheless, some aspects of how ancien régime societies and those who governed them operated warrant examining the differences between the recent past and the less recent past while focusing on the early-modern origins of the contemporary social and communicative processes noted above. These include key issues like the relationship between confidentiality and disclosure, controls imposed on publication and interpretation, freedom of speech and of the press, the speed with which information is communicated and disseminated, and the role of the authorities in emergencies: in such domains, although some elements are common to both the early modern period and the contemporary period, similarities are vastly outweighed by the differences. Moreover, the emergence and spread of printed matter shaped the interests, tastes and expectations of the general public over the course of the early modern period, and periodicals made readers familiar with the idea that knowledge could grow and be enriched over time.

Early modern societies often saw information gathered through official channels as arcanum imperii, or state secrets, in accordance with the secretiveness of ancien régime procedures, so most of this information remained inaccessible by the general public. Acquiring expert information, data and opinions, a fundamental aspect of governance, was effected through confidential official channels accessible, at least in principle, only by the monarch, the monarch’s most trusted advisors and some top officials. Even opinions about certain natural phenomena provided to the authorities by specialists such as philosophers, naturalists or doctors were usually only circulated in official circles and then archived without being circulated more widely in print20.

Maintaining tight control over communication and keeping sensitive information confidential was already difficult for church and state authorities in normal times. However, when confusion and fear prevailed, as in times of war, invasion, rebellion, epidemic, disputed succession and other calamities, there was a greater propensity for information to be leaked and then shared by a potentially vast audience through informal networks operating at different scales. At a local scale, especially in towns and cities, the potential commercial or non-commercial market for news encouraged sharing. News travelled swiftly through the streets, piazzas and marketplaces, or when people gathered for church services. It travelled in writing or by word of mouth, as manuscripts or in print, whether the news was official or mere rumour, and texts and images were combined to the point of confusion21. In addition, cities were also often hubs for international networks where news travelled informally in the private correspondence of ambassadors, politicians, merchants, aristocrats, the clergy and men of letters. This multitude of actors in or close to official channels transmitted information from one area to another and sometimes from one continent to another, spreading knowledge and shaping opinion22.

Research into information is a field that lends itself to large-scale investigation, covering the intensified dissemination of news across great distances and in different parts of the globe. However, there is ample evidence of the risks associated with providing a top-down history of information that focuses on sources such as gazettes or pamphlets, thus potentially masking local differences and asymmetries and providing a homogenised vision that fails to recognise the fragmentation or semi-independence of different spheres of communication23. Indeed, information subnetworks were to a certain extent independent of one another, yet connected in some ways. Researching times of emergency, when some channels of communication were disrupted and new ones emerged, reveals the diverse and asymmetric nature of communication and the obstacles and opportunities created by the distances that information needed to cover and the slow pace at which news travelled, especially in the early modern period.

Unexpected extreme events therefore stimulated an appetite for news and explanations, expanding how and where information was communicated and fostering multiple interpretations which were at times contradictory and even potentially dangerous. This was another reason why there was rivalry between church authorities, state authorities and other influential groups over the control of the flow of information. They entered the fray, directly or indirectly, to assert their own interpretation of extreme events in order to maintain or increase their influence and to attack or weaken their adversaries. This rivalry was most evident in matters of information and communication, as controlling news and opinion had, then as now, a crucial role in crises that affected large numbers of people24.

As noted above, over recent decades historiography has emphasised the need to examine how different channels interact and to consider the written word as part of a more complex system of diverse forms of media. However, recognising the intermedial nature of communication and the diversity of the media used, as well as the importance of oral communication, images and non-verbal communication does not mean ignoring the growing importance of the written word over the course of the early modern period, and the printed word in particular, and its crucial role in determining power relationships25. Indeed, focusing on the interaction of different media, as exemplified by many of the papers in this volume, can help to bridge the gap between cultural history’s usual focus on the production and diffusion of books, words and images, and a history of institutions that until recently devoted little attention to the social aspects of official documents, to the social history of knowledge or to the mindsets that shaped how government bodies operated26.

4. Manuscripts, printed texts and periodicals in times of emergency

Important recent work on the relationship between information, the development of knowledge and how sovereignty was exercised in the Hispanic Monarchy builds on Arndt Brendecke’s monograph on the first centuries of the expansion of Spanish rule27. His research addresses the emergence of modern states, government at a distance and the politics of knowledge from the perspective of the history of archives and information, of clientelism and of the interplay between local knowledge and the heart of the empire. He questions the commonplace that equates colonial power with extensive, detailed and confirmed intelligence. The assumption that the extensive use of writing by the imperial authorities was a feature peculiar to the Hispanic Monarchy has been emphasised by historians as well as by contemporaries28. Brendecke questions the Crown’s supposed omniscience and omnipotence in its dominions. Despite measures to acquire extensive objective knowledge (entera noticia) of its new territories, the accounts received were substantially shaped by the specific interests and culture of those providing the information, reflecting the expansion of patronage networks in the overseas territories.

Work of this kind is also of fundamental importance to the papers in this volume. The first section (Controlling the flow of news) addresses the issues of interpretation and methodology raised by research on communication. The three papers deal with questions relating to the confidentiality and disclosure of information, to the use of information in times of emergency and to the political and material dynamics of disseminating news.

Tamar Herzog’s contribution raises the fundamental question of whether the impressive collections of petitions, relaciones, trial records and so on stored in Hispanic Monarchy archives were regularly consulted and used to improve knowledge about the new territories, and whether consulting them was actually a prerequisite for making decisions. Herzog shows that, although the Council of the Indies had access to a plethora of records, most petitions that reached Madrid were treated without reference to earlier petitions, and the councillors appear to have been unaware of any pertinent precedents. Herzog sheds light on how archives were built and used, and argues that they were relatively insignificant elements of the history of knowledge in the early modern period. Fernando Bouza’s paper, on the other hand, offers an apparently different interpretation of the use of knowledge that was compiled during a crisis, but his work is based on a different corpus of documents and adopts a different analytic perspective. Bouza analyses the dissemination of news about outbreaks of plague and extreme environmental phenomena in Portugal and Spain by considering not only printed texts and manuscripts, but also images, processions, ex-votos and the increasingly powerful murmur of the streets. Indeed, while calamities triggered the expression of authorised views, they also led to other views being expressed, thus adding to the complexity of the multifaceted public debate. Bouza shows how a corpus of knowledge about plagues was created based on an archive that could be used when the emergency re-emerged. Virginia García-Acosta’s contribution on the Viceroyalty of New Spain addresses extreme weather events during the final phase of the colonial period, focusing on how local bodies responded to information received. The events caused agricultural disasters, which in turn produced discontent, dissatisfaction and anger in the closing decades of the eighteenth century. Using archival information, printed texts and newspapers, García-Acosta analyses how the Bourbon authorities responded to unexpected crises and argues that their weak, slow and inefficient response contributed to the growing popular discontent.

The second section (From relaciones to periodicals) contains contributions that differ in focus, analytic perspective and the nature of the sources used, but are linked by the issue of the impact of the pre-periodical press (e.g. broadsheets, pamphlets, relaciones, relazioni) and periodicals (e.g. gazettes, newspapers, journaux savants). As Carmen Espejo-Cala noted a few years ago in a paper reviewing recent research on communication and the press in modern Europe, ‘We must bear in mind that the birth of journalism occurred in times of turmoil, with political, religious and communicative tensions’29. This observation not only highlights, in general terms, that research on times of emergency can advance our understanding of the dynamics of information in ancien régime societies, but also that the urgency and turmoil generated by emergencies produce styles and methods of communication that over time become stable and lasting. Seeing the history of print exclusively in terms of a radical paradigm shift or a revolution is no longer a tenable point of view30. However, it is important not to lose sight of the changes that technological or logistical innovation brings about at the heart of information systems, such as the consolidation of postal networks or transport31, or the emergence of new media and their impact on communication32, which did not lead to the disappearance or decline of existing media, but triggered some repositioning33.

Over the course of the early modern period, the appetite for news of extraordinary tragic events grew, creating a news fever that became very evident in the early seventeenth century, in particular with the outbreak of the Thirty Years’ War34. The authorities were forced to admit that they could not suppress people’s curiosity about such events or keep them secret, so they resorted to applying increasingly detailed filters and controls to written accounts, in particular those appearing in the press. As in the case of book censorship, as recent key works have shown35, both church and state authorities always recommended alternative reading material to replace what was forbidden even at the height of censorship, as simply banning certain texts would not have been effective. Secrecy was partially sacrificed to the need to satisfy popular demand36.

Three of the papers in this section analyse the stylistic devices and narrative strategies used in newssheets and gazettes, exploring the relationships between information networks and communication strategies in times of emergency. Annachiara Monaco examines a corpus of relazioni in Italian that recount disasters that struck the Hispanic Monarchy in the seventeenth century, from the 1609 Seville floods to the 1693 Eastern Sicily earthquake. The analysis of syntactic, rhetorical and lexical devices shows how the authors and their patrons used these printed texts to achieve their communicative objectives of providing information, stirring emotions and shaping opinion. The paper highlights the stylistic and narrative devices used to provide assurances about the reliability and accuracy of the information, such as extensive details about the cadavers and the rubble, hyperbole, images that evoked monstruous infernal beings and the like. The aim was to generate awe in readers, and to convince them that the communities affected could be helped through penitence and prayer under the guidance of those in authority. Printed relazioni are also the subject of Valentina Sferragatta’s analysis, which focuses on one of the most destructive eruptions of Mount Etna, that of 1669. The study of the linguistic and rhetorical devices used in these texts provides valuable insights about how the eruption was portrayed, and reveals how the descriptions shifted according to the author’s views and objectives. A close comparison of the printed version of one account with the manuscript on which it is putatively based suggests that the writers of printed material that was authorised and promoted by the city’s religious and political bodies adopted specific strategies to promote specific images of Catania and its institutions. Vincenzo Leonardi’s paper on the 1661 Malaga flood compares manuscripts, pre-periodical newssheets (relaciones) and gazettes produced just as periodicals were becoming established in Spain despite the rise of the notices and pamphlets that furnished gazettes with content. Leonardi’s investigation of intertextual relations and significant shifts in textual structure reveals that the narrative patterns used in newspapers underwent substantial structural changes to adapt to the world of serial information.

Details

- Pages

- 476

- Publication Year

- 2023

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783631904602

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783631904619

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783631869628

- DOI

- 10.3726/b21360

- Open Access

- CC-BY-NC-ND

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2023 (December)

- Keywords

- wars epidemics political history cultural history News periodicals information networks media disasters

- Published

- Berlin, Bruxelles, Chennai, Lausanne, New York, Oxford 2023. 476 pp., 15 fig. col.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG