Building Multispecies Resistance Against Exploitation

Stories from the Frontlines of Labor and Animal Rights

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

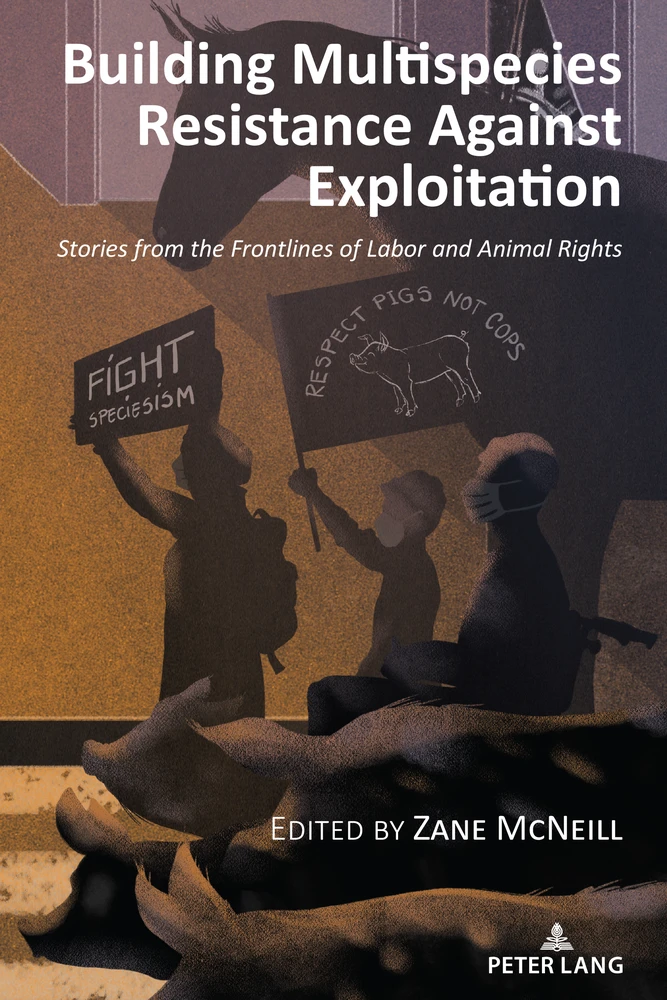

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Section 1 The Necropolitics of Laboring in the Abattoir

- Unfulfilled Resistance: The Labor of Not Surviving

- Violence Begets Violence: The Necessity of Solidarity with U.S. Slaughterhouse Workers

- Section 2 The Animal Advocacy Nonprofit Sector and the Reification of Carceral and Racial Capitalism

- Undercover Investigations and Carceral Veganism: The Limitations of “Removing the Veil”

- Death or Deportation: A Nebraska-Based Study of the Exploitation of Immigrant Workers in Meatpacking Facilities and the Immigration Consequences of the Animal Protection Movement

- Laboring for Nonhumans: An Autoethnography of an Animal Rights Non-Government Organization

- Horses of a Different Color: Reckoning with Race in the March for Animal Rights

- Section 3 Moving towards Multispecies Liberation

- Abolish the Meat Industry: A Roadmap for Transforming Animal Liberation from a Single-Issue Cause into a Mass Movement

- Animal Liberation, Class and Direct Action for Total Liberation

- An Essay on Total Liberation: Marcusean Insights for Catalyzing Transformation

- Concluding Thoughts

- Notes on Contributors

- Series Index

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Dani Green for believing in the vision for this project and Laura Schleifer and Riley Clare Valentine for their feedback on the introduction of this collection. I also want to hold space for my current mentors, Z Williams, Erika Unger, Sandy Freeman, and Jenipher Bonino, who are supporting me as I navigate the intersections of legal, animal, and labor advocacy spaces. Thank you all for working towards total liberation. Lastly, I want to thank VegFund for providing this project with a grant and supporting my work.

Introduction1

Zane McNeill

In July 2023 at least three children died from on-the-job injuries at industrial nonhuman animal slaughter facilities in the United States. One such case, Duvan Tomas Perez, 16, died at a Mississippi poultry plant after becoming trapped in equipment on a conveyor belt. Perez was entering ninth grade and was hired in violation of federal child labor laws, which prohibit employers from hiring anyone under eighteen to work in slaughtering, processing, and packing facilities.2 Perez’s death prompted the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) and the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) to open investigations into the fatal incident, which was the plant’s second death in two years.3

An investigation by the DOL Wage and Hour Division in February 2023 found that more than one hundred children were illegally employed in hazardous jobs.4 Packers Sanitation Services Inc., one of the country’s largest food safety sanitation services, was found to have employed children at 13 meat processing facilities in eight states. The facilities included those of Tyson Food Inc., JBS Foods, and Cargill Inc. Many of the minors were working in hazardous occupations and were routinely forced to work overnight shifts. The DOL fined Packers Sanitation Services Inc. more than $1.5 million for violating the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) by illegally employing children.

Seemingly in response to the federal crackdown on child labor violations in the meatpacking sector, states including Arkansas, Iowa, Ohio, Minnesota, New Hampshire and Wisconsin introduced legislation that would loosen child labor laws and encourage companies to hire children to work in hazardous workplaces.5 On March 7, 2023, Governor Sarah Huckabee Sanders (R-Arkansas) signed reactionary House Bill 1410 into law, which labor and child advocates hypothesize will make it easier for companies to employ children. A week before Governor Sanders signed the bill, Tyson’s Green Forest plant in Arkansas was implicated in the DOL investigation for employing at least six children and was fined $90,828.6

The so-called meat barons who own the means, or literally meat, of production, extract wealth by “processing its racialized workers and the carcasses they dismember under dangerous and exploitative conditions to squeeze every last cent from their drooping limbs,” in the words of historian William Horne.7 This system, Horne contends, is built upon the “evolution of the racial state,” and its entanglement with capitalism, surveillance, and circularity. Horne asserts that “The racial capitalism that animates American food production […] remains the central driving force facilitating poor wages and treatment in the rest of the economy.”8 This extractive industry, which milks all of its profit from the human and nonhuman animal bodies within its reach, depends on the commodification and precarity of its laborers.

The lives of children employed at slaughterhouses, like the lives of the nonhuman animals slaughtered and dismembered in the facilities in which they work, are rendered killable by the necropolitical animal agriculture industry. The term “necropolitics” refers to the politics—that is, the use of social and political power—to decide who lives, who dies, and how someone should live or die.9 As described by Marek Muller, who builds on the work of political theorist Achille Mbembe, “The necropolitical refers to the state’s potential to make certain bodies killable, such as naming enslaved bodies ‘chattel’ to deny them of their personhood and subsequently of their legal rights to life and liberty.”10

While Mbembe describes the necropolitical subject as being kept in a state of unending injury, Muller uses the term zombification to express the social process in which one “becomes socially dead physically, psychologically, and culturally.”11 Muller uses this frame to explore how the nonhuman animal agriculture industry not only “places animals in the role of the ideal socially dead subject (the chattel slave),” but also animalizes and dehumanizes the human workers. “Slaughterhouse subjects, human and animal, exist in uncomfortably close proximity to one another, thus contaminating each other with the particularities of their liminalities and further reifying a colonial sliding scale of humanity,” Muller explains.12 In other words, under racial and carceral capitalism, necropolitics renders not only nonhuman animals as “slaughter-able,” but also humans who are animalized. Racism’s “ontological plasticity,” as posited by Zakkiyah Jackson, “render[s] one’s humanity provisional,” in which “black(ened) people are not so much as dehumanized as nonhumans or cast as liminal humans nor are black(ened) people framed as animal-like or machine-like but are cast as sub, supra, and human simultaneously and in a manner that puts being in peril.”13 In other words, white supremacy constructs and relies on a social malleability of racialized people, and its entanglements with surveillance, control, and carcerality, in order to extract capital from its laborers.

Specifically, the meat-processing industry depends on carcerality in tandem with racial capitalism which evolved out of the convict leasing of the Jim Crow era, which itself evolved out of chattel slavery.14 This system transforms human and nonhuman bodies into commodities whose labor is consumed and capitalized upon by the elite class. Thus, this collection asserts that there is a shared exploitation between laborers—human and nonhuman alike—which is designed within and by a system built on carceral and racial capitalism.

Embedded deeply within this necropolitical racial and carceral capitalist system is speciesism, or the assumption that individuals deemed (fully or solidly) “human” are superior to other(ed) individuals, human and nonhuman alike, who are deemed “animals.” Speciesism is inherently hierarchical and simultaneously justifies the exploitation of nonhuman animals and animalized humans as relatively invisible and unquestioned. “This system of normalized harm forms the foundation of so much economic activity and is impossible to ignore when thinking about animals and organizations,” as Coulter explains.15

Industrial agriculture depends on speciesism’s entanglement with white supremacy and racial capitalism depends on this hierarchized relationship between race, animality and humanity. As Syl Ko explores, humanness is a “certain way of being, especially exemplified by how one looks or behaves, what practices are associated with one’s community, and so on…this means that the conceptions of ‘humanity/human’ and ‘animality/animal’ have been constructed along racial line.” In this racial capitalist landscape, meatpacking workers, through ontological plasticity, are simultaneously both human and nonhuman: human as legal “employees” of a company and at the same time rendered nonhuman, “killable” commodities.16

Speciesism renders the idea of nonhuman animals as laborers perplexing. Blattner, Coulter, and Kymlicka explain that “On the one hand, exploiting animal labour is one of the paradigmatic ways in which humans use animals…. Animal labour has been a site of intense instrumentalization, exploitation, and degradation.”17 While nonhuman animals are rendered property as objects owned by the industry, they are also autonomous individuals who suffer compulsory labor. As suggested by Blattner, “recognizing animals as workers does not mean endorsing their exploitation or stripping them of rights to refuse work. Rather, we should recognize animals as exploited workers”18 For example, as explored by Carol Adams in her groundbreaking text, the Sexual Politics of Meat: A Feminist-Vegetarian Critical Theory billions of animals are exploited for breeding to literally reproduce the violent structures of which they were born.19 Millions of other animals, as Catherine Oliver explains in her chapter, experience metabolic labor, or are born to grow and to die. This necropolitical labor saturates the experiences of nonhuman animals rendered “killable.”

Both human and nonhuman laborers are exploited for capital accumulation. “If some do not work—those who possess the power and means of production—it is because others do the work for them,” Porcher and Estabanez explain. “Work seems therefore to be a world of competition and individualism, but also an essential motor of inequality and discrimination, in particular in the building of socio-professional hierarchies.”20

Animal activists have alleged that their labor too has been exploited within the animal advocacy nonprofit sector (AANS).21 Activists have alleged that white goals and interests are centered in the missions of many of these organizations, reifying the hierarchies which the animal agriculture sector is similarly predicated on because of the predominantly white racial makeup of management and funders. This racial dynamic leads to organizational cultures that overwork, alienate, and marginalize Black, Indigenous, People of the Global Majority (BIPGM) animal advocates. There is an embedded neoliberal capitalist culture, or roots in the nonprofit industrial complex, which has led to incidents of sexual harassment and sexual and racial discrimination in the sector. These problems lead to issues of sustaining diversity in the workforce.22 As Tiffany Lethabo King and Ewuare Osayande explain, the nonprofit industrial complex has been used to by elite to maintain racial hierarchies, capture and undermine social movements, and shield models of capitalist extraction:

On the surface, progressive philanthropy is an attempt by the Left to advance the movement forward by bolstering it with more resources. But rather than putting more money into the hands of non-profits that address the needs of the marginalized, the results have been little more than a few cosmetic adjustments to make capitalist foundations appear progressive and the Left complicit in supporting systems of oppression, exploitation, and domination.23

This collection posits not that the AANS has similarly been constructed to constrain movements for human and nonhuman animal liberation and that, because of this, the AANS reproduces such hierarchies internally. Workers in the AANS have voiced concerns regarding workplace bullying, the silencing of worker-activists’ voices, and retaliation against worker-activists who raise concerns about labor practices in the sector. Particularly concerning is that researchers have found that 48.6% of paid AANS workers have experienced discrimination, unfair treatment, harassment, bullying, or abuse in their previous five years of employment.24 This seems to lead to attrition and efficacy issues, as 40% of advocates leave organizations in the AANS because of problems with leadership and 22.8% of advocates left previous roles because of burnout and traumatic stress. “The mainstream animal movement, as well as ‘good food’ movement’s most influential leaders and frameworks, are simply used as an extension of [sic] empire,” Dr. Breeze Harper explains. “Neoliberal-capitalist-whiteness sold to the average untrained mind as ‘green’ or ‘social impact’ when the outcomes will still be concentration of power amongst those (mostly white men, but there are also those who may not be white men but uphold [sic] the power structure) who have held, maintain, and created power for centuries.”25

For example, in the summer of 2020, staff of the Animal Legal Defense Fund (ALDF) who had the intent to unionize, the initiative of which was primarily initiated by dissatisfaction with the organization’s lack of response and public solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement after the murder of George Floyd, was met with classic union-busting tactics.26 On December 14, a supermajority of ALDF’s staffers signed cards to form a union27—the first at an animal protection organization. ALDF management’s response was to refuse to voluntarily recognize the union28 and to hire notorious union-busting firm, Ogletree Deakins, to advise management on how to proceed.29 Staff members reported being forced to attend rolling union-busting and captive-audience meetings to discourage unionization.30 This response to the unionization effort led reporter Hamilton Nolan to describe the Animal Legal Defense Fund as “busting its union with a smile.”31 As of the writing of this introduction (summer 2023), ALDF has not yet finalized their union contract negotiations—three years later.32

ALDF’s refusal to challenge the carceral State and condemn white supremacy is not isolated. In fact, the AANS has also historically vilified meatpacking and slaughterhouse workers and directly worked with the carceral State to imprison BIPGM. Many of the most prominent organizations in the AANS have been critiqued for engaging in this carceral veganism, a philosophy which, as defined by political scientist Riley Clare Valentine, does not “question the normalized violence that is behind prisons and jails…[and] supports white supremacist ideas of who is the enemy and from whom society needs [to] be protected.”33

The children as well as adults who are laboring and dying in meatpacking plants, the labor of nonhuman animals themselves and the work done with and for animals by animal activists are all exploited and oppressed by the same interconnected systems of oppression which are subcategories of what Kendra Coulter calls “animal work.”34 If the AANS relies on carceral logic which “reinforces systematic violence against humans and nonhumans,” the reinforcing systems of speciesism, necropolitics and racial and carceral capitalism will continue to harm all animal workers.35

The present collection, Building Multispecies Resistance Against Exploitation: Stories from the Frontlines of Labor and Animal Rights, troubles the relationship between these subcategories of animal work and interrogates the politics that undermines efforts to achieve interspecies solidarity, namely racial and carceral capitalism and the necropolitics embedded within it. To do so, this book centers activist-scholars who have worked in the movement for animal liberation and who question the ways in which the AANS has reified racial and carceral capitalism, not only undermining its potential to achieve interspecies solidarity and animal liberation, but also weaponizing oppressive structures against other animal workers, such as meatpacking and slaughterhouse workers, as well as animal activists in the sector.

This collection posits three questions. (1) What structures of violence and oppression are experienced and shared by human and nonhuman laborers working and dying in these necropolitical facilities? (2) If there is an intersection between class and species, which, in turn incorporates race, gender, abilities, and other categories of oppression, in which ways is the contemporary animal advocacy nonprofit sector reifying or disrupting these hierarchies in its mission towards animal liberation? (3) If there are classist and racist biases in AANS, how can the AANS incorporate social class in dialogue with the liberation of nonhuman animals in order to build strategic alliances and coalitions between social movements and political subjects? To answer these questions, this collection brings together scholarly works by various scholar-activists on the interconnectedness of human and nonhuman labor, the differences and similarities of human/nonhuman oppression, the possibilities of alliances and coalition-building for total liberation, and the challenges and opportunities of incorporating a critical class perspective into animal liberation work.

The first section, “The Necropolitics of Laboring in the Abattoir,” examines the labor landscape of animal work—specifically the labor of, and resistance to, killing and being killed in the slaughterhouse. The chapters in this section, “Unfulfilled Resistance: The Labor of Not Surviving” by Catherine Oliver and “Violence Begets Violence: The Necessity of Solidarity with U.S. Slaughterhouse Workers,” by Marek Muller explore the entanglements of class, labor, and resistance in human and nonhuman animal communities exploited by the industrial agriculture sector. Specifically, these chapters disrupt expectations about what constitutes labor and who has choice, autonomy, and recognition of rights under racial capitalism. These chapters posit, as described by Oliver, that “labor and work aren’t exclusively human, and the concept of animal rights has existed in some form for centuries, and nor is resistance solely a human activity.”

Details

- Pages

- XII, 194

- Publication Year

- 2024

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781636675619

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781636675626

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781636675602

- DOI

- 10.3726/b21657

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2024 (March)

- Keywords

- Animal rights human rights consistent anti-oppression total liberation Vegan politics critical theory capitalism meatpacking workers slaughterhouse workers activists nonprofit Zane McNeil Building Power through Multispecies Resistance Lessons from the Frontlines of Labor and Animal Rights carcerality necropolitics labor rights animal labor

- Published

- New York, Berlin, Bruxelles, Chennai, Lausanne, Oxford, 2024. XII, 194 pp.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG