Digital Literacy

A Primer on Media, Identity, and the Evolution of Technology, Second Edition

Summary

This updated edition explores a variety of approaches to digital literacy, including prescient work by media theorists, the historical influences of legacy media, the contemporary transformations of the digital environment, and the way our communication ecology is constructed. The book argues for an understanding of the changes in traditional media, the rise of Big Tech, and the challenges these pose to privacy and to democratic ideals.

Important themes explored in chapters across the book include digital identity, the internet as infrastructure, the web as a collaborative tool, and domestic and global digital divides. The new edition also explores digital literacy and the pandemic, as well as the growing body of research around the effects and impact of the digital technologies we use every day. Also included are useful Applied Skills Appendices outlining core areas of digital practice.

The text is an ideal resource for students and scholars of mass communication, media literacy, digital information literacy, and digital technology courses, as well as for all those wanting to know more about the deep on-going impact of communication technologies on our lives.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- What’s New in the Second Edition

- 1. Introduction: The Book Starts Here

- 2. The Evolution of Contemporary Media: Recalling a Collective Past, Sharing a Fragmented Present

- 3. Corporate Colonialism: Why Ownership Matters

- 4. The Medium Is the Mass-Age: Revisiting Marshall McLuhan

- 5. We’re Not Here: The Cultural Consequences of All Me, All the Time

- 6. Digital Identity: Options, Opportunities, Oppressions, Impressions

- 7. A Social Experiment: Digital Tech at Its Best & Worst

- 8. Much to Lose: The Symbiotic Relationship Among Journalism, Technology, & Democracy

- 9. It Really Is a Thing: The Internet as Infrastructure

- 10. If It’s Not the Internet, What Is It? The Web as a Collaborative Tool

- 11. From Neighbors to Followers: Rethinking What It Means to Be Part of a Community

- 12. Haves, Almost Haves, & Have Nots: The Domestic Digital Divide

- 13. Connectivity & Digital Disruption: The Global Digital Divide

- 14. Remixes & Mashups: Appropriation of Cultural Goes Digital

- 15. Yours, Not Yours: Digital Surveillance & the Privacy Paradox

- 16. Can’t Put the Genie Back in the Bottle: Now What?

- Applied Skills Appendices

- Appendix 1 Digital Communication Etiquette

- Appendix 2 Professional Use of Social Media

- Appendix 3 Writing for Digital Media & Content Credibility Cues

- Appendix 4 The Care and Reading of a URL

- Appendix 5 File Management

- Key Concepts

- Index

Acknowledgements

Susan Wiesinger extends her limitless appreciation for John Wiesinger, an exceptional first-line editor and keepin’ it real content evaluator. As Kenneth Burke would say, without whom not.

Additional thanks to:

- − The tech journalists and academic researchers who keep close watch on tech trends and cultural impact. Your work is extraordinarily valuable and we’re proud to have aggregated some of it in this book.

- − The students of JOUR 255, “Digital Literacy & Media Technologies,” at California State University, Chico, who helped refine the work and offered feedback on final chapters. (Beyond that, they are an endless source of inspiration.)

- − Regan Penning and Sofia Thomas, who proofread the manuscript as students in the above-noted class, taking the “typo bounty” seriously enough that I came to think of them as my editorial assistants.

- − The anonymous reviewers whose time and energy reviewing earlier versions of the manuscript greatly strengthened the final book.

- − The University of Oklahoma, which provided grant funding for licensing of chapter comics.

- − Vin Crosbie, who provided extraordinary feedback of an early draft of Chapter 2, inspiring the author to do more.

- − Josh Boyd, who nurtured my research and writing as a student at Purdue University and made me think I could do all the things. More than two decades later, I feel that I have, which I attribute to / blame on his influence.

←vii | viii→Ralph Beliveau says this work was dependent on Abby and Martha, who continue to shame him about his media experience … or lack thereof.

Additional thanks to:

- − Laura, the best teacher anyone could ever have.

- − Marilyn Beliveau, for making learning a great thing.

- − Mike Dolesh for giving me troubling things to read when I was impressionable, which made me a better person. He was the best teacher I ever had.

Any mistakes are the sole responsibility of the authors.

What’s New in the Second Edition

Digital literacy is a question that keeps changing, and much has changed since the first edition of this book.

In drafting the second edition, we’ve reviewed, updated, and reorganized, as well as added a significant amount of new content around the concepts of media ownership, consequences of Big Tech dominance, impact of social media, individual engagement, physical impacts of ubiquitous tech use, global effects of boundary-crossing information, environmental costs of tech, media literacy, and social costs of disinformation.

For example, the spread of COVID-19 and subsequent slow burn of a pandemic marked a significant disruption to our collective worldview and sparked deeper analysis of the consequences of our reliance on mediated communication technologies. During the infamous lockdown of spring 2020, our in-person connections with friends, family, coworkers, teachers, and classmates were abruptly stopped. Of course, we all know the plot of this particular story: video teleconferencing and streaming video to the rescue.

While we’ll weave discussion of digital literacy and the pandemic into various chapters ahead, it’s worth noting here that we learned at least a couple of things about ourselves:

- 1. Mediated contact, whether face-to-face via Zoom or scrolling through social media feeds is a not a satisfactory replacement for human interaction for everyone; and,

- 2. We crave at least the semblance of common culture.

The former has emerged as a collective increase in anxiety and lost learning opportunities that will affect our communities for years to come, while the latter provided lighter moments of connection along the way—from cursing Zoombombers to collectively binge watching “Tiger King” and multiple seasons of “Schitt’s Creek” from within our lockdown bubbles. The conversations that resulted on social media made us feel like we were sharing something in the midst of significant uncertainty.

We’re also hoping the second edition piques interest in the growing body of research around the effects and impact of the digital technologies we use every day. We’ve embraced the second edition as an aggregation of some of the best tech journalism and research available—critical work by knowledgeable folks that is worthy of your consideration.

Chapter 1

Introduction: The Book Starts Here

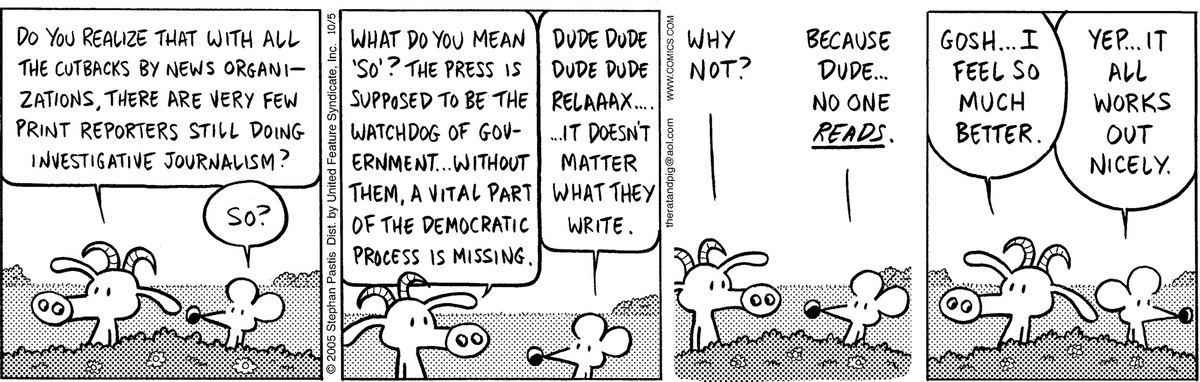

Figure 1.1.What does it mean to live in an information landscape where filters—aka journalists—are no longer the only people to interpret, document, and draw the public’s attention to the issues and events that continually shape and change our world? Pearls Before Swine © 2005 Stephan Pastis. Reprinted by permission of Andrews McMeel Syndication. All rights reserved.

OK, honesty time: How much do you read? We mean really read—as in sit down with a single means of information delivery (aka a book, magazine, or newspaper). And how often are you criticized or feel guilty for not reading enough?

A hallmark of digital living is that you likely are consuming more information than any previous generation, but you’re not necessarily reading it. We’re all skimming, skipping, and surfing as we navigate an endless ocean of content via a veritable flotilla of media and digital device choices.

The flood of information always has been there, but prior to the Internet it took owning a printing press or having access to the airwaves to transmit information to the masses. In an information landscape dominated by print and broadcasting, only certain people could participate. And those people—mostly journalists—were held to particular newsgathering practices and values that effectively excluded the public.

Not surprisingly, when the internet opened participation to the rest of us, many took the opportunity to put their unvarnished observations, announcements, meals, and minutiae directly online, cutting out the traditional mediator. And so, the floodgates fell and the information tsunami came roaring through.

Media Literacy, Digital Literacy … What’s the Diff?

It’s possible your grasp on the need for media literacy is somewhat weak, yet you’re now being asked to grapple with digital literacy. That means there’s a bit of catching up to do.

Media literacy is the ability to think critically about the endless flood of messages sent by media organizations (e.g., films, shows, news reports) to a general, undifferentiated public, as well as those we receive via our highly individualized social media feeds. It’s all about how we interpret and respond to those messages—consciously or unconsciously.

Traditional media literacy assumes a passive population that consumes a significant volume of messages, from which a common culture is built. Common culture emerges when there are touchstones—shared, collective experiences—that bind us together as a society.

Think of it like water-cooler culture: People taking a break, standing around the office water cooler, and talking to coworkers about a television show that everyone watched last night. If you didn’t watch, you’re left out. And next week you watch so you can share in the water-cooler conversation.

Digital literacy is different, largely because technology has changed how we communicate, what we consume, across what platforms we consume it, and via what devices. Digital literacy also is concerned with our interpretation of and response to messages, but is more focused on the cultural impact of the technologies delivering the information.

Digital information typically involves both passive consumption and active production of highly personalized messages. It holds the promise of being interactive, where producers become audiences for users, and users produce content for each other. But from a historical perspective, the result is both fragmentation and the erosion of common culture.

Think of it as spoiler culture: People still take work breaks, but they don’t leave their desks (or sometimes even their homes). Instead, they turn to digital tools that enable the near-instant transmission of cultural symbols from person to person via internet-connected digital devices.

Because we are all consuming information across different channels, we don’t share reference points that are anchored in time and space. For example, you may choose when to watch your favorite television show and via what medium, rather than being held to a network schedule and required to watch on a television set. “Gilligan’s Island” from 1964 on Hulu? Check. (Just don’t tell me how it ends.)

The difference between water-cooler culture and spoiler culture—media literacy versus digital literacy—is the method of transmission.

Instead of person-to-person and media-to-masses, spoiler culture is a digitally mediated world of individuals. Even if every person were on the same social media platform, it is unlikely that common culture would emerge. That’s because it’s not the platform that matters; it’s the information feed. And every digital feed is unique. Each is customized to reflect the user’s personal interests, values, history, and increasingly, brand.

In the past, television was a social medium that encouraged people to watch shows together. Even if you weren’t in the same household, you could share the experience of having watched the same show (aka common culture).

Digital literacy means understanding “television” as both a social and a solitary thing to do. Sometimes we gather around the TV. Sometimes we watch on our digital devices alone—or perhaps even chat with other people on similar devices in different places at the same time.

It’s increasingly rare for individuals to watch what everyone else is watching or even consume information across one digital device at a time. In fact, you may be physically in a room watching TV with others, while skimming content on a laptop or tablet and interacting with others on a smartphone.

For that matter, television no longer exists as a stand-alone cultural norm for a decent chunk of the U.S. population, particularly those who have given up, or never signed up for, cable TV. A great deal of what might be termed TV content now is consumed on digital devices, including TVs, accessed via video streaming services.

If you’ve ever watched a made-for-TV series via a streaming service, you’ll note that each episode is the same length and there are logical points where advertising would have been placed. Those shows were created for a world bound by time.

If you watch a made-for-streaming series or user-generated video on YouTube and choose not to pay for an ad-free service, you’ll note that the episodes can vary wildly in length and ads may be dropped in at the most inopportune times. They’re not pauses built into the plot, they’re payment for watching. Those shows were created for a world bound by individual preference.

Existing and emergent technologies have put more of everything at our fingertips and in our brains than ever before. We have not discarded previous media as new have arisen; instead, we have accumulated—print, film, radio, television, cable television, internet, World Wide Web, social media, apps, and so on.

A digital information environment is one in which the medium—the device through which we access information—has a larger social impact than the message—the content we receive through a particular medium.

As a result, we need to critically consider what it means to be a citizen in an information landscape that not only has been individualized but also is constantly in flux.

We also need to understand that consumables—from user-generated content to social media feeds to streaming video—have increased exponentially. And much of that content is being consumed online and alone.

One concern with information inundation is that people no longer will be interested in what is real or even relevant to their physical lives, disrupting our ability to reason and participate reasonably in a democratic society. Media theorist Neil Postman speculated that we would become increasingly immersed in “a peek-a-boo world, where now this event, now that, pops into view for a moment, then vanishes again.”1

Postman wasn’t opposed to entertainment, but he was conscious of increasing levels of distraction. He understood that people need the escape that entertainment offers, but he predicted that the rise of electronic media and increased focus on entertainment could have a two-fold effect on common culture and civic participation. In summary,

- 1. People wouldn’t know what actually affects their lives; and,

- 2. They wouldn’t know what they should do, even if they could figure it out.

If No One Is Gatekeeping, How Do We Know What’s True?

In the world that print once ruled, the mass media tended to be assessed as purveyors of “capital-T-Truth,” as in there is a Truth that can be discovered, verified, and agreed upon. This makes some sense, given the heavy use of newspapers as historical archives. The fact that print stories were finished and frozen in time granted them a degree of credibility not possible from any other medium.

Digital reality is more complicated, largely due to the volume of information being contributed from a multitude of voices. Because both journalists and the public are participating, this information flow often is viewed as “lowercase-t-truth,” which implies that most observations are not the truth but simply one perspective from one point of view at one point in time. Or, as with Wikipedia, a negotiated perspective.

While this muddies source credibility on many levels, we don’t necessarily want legacy media to help out with this problem by gatekeeping the flood of information.2 We don’t want the media to tell us what to think about, but want to discover the relevance to our lives ourselves. We want highly personalized content and to have the ability to share, challenge, and fact-check it in real time.

Paradoxically, content no longer is filtered exclusively by journalists but—by design and necessity—is filtered by complex computer algorithms that underpin browsers, search engines, and social media.

In short, our content is still subject to gatekeeping, but by the platform media companies that act as our conduit to the content—most notably the products of Alphabet (YouTube, Google) and Meta (Facebook, Instagram).

This type of dissemination gives corporations great power over individual information consumption and privacy, even as it allows people to think they are choosing what information they want to consume and from whom. It’s also indicative of our existence in a post-narrative world, where overarching stories, an informed electorate, and the quest for Truth are being challenged by personal opinions, divisive ideologies, and individual truths.

As a result, much of what we consume reflects an algorithm-constructed impression of our own values and beliefs right back at us. We chat, message, comment, text, and like; we post, pin, subscribe (as long as it’s free), and share—effectively witnessing everything from snacks to global politics through the screens of digital devices.

And this is an environment that allows individual users to share their knowledge—and their biases—to a much wider audience than ever before.

One need only think of Wikipedia to understand the ways in which the web allows users to collaborate and build deep reservoirs of knowledge about an endless range of topics. But as any high school teacher will tell you, Wikipedia is a starting point, not a definitive source of information—and you should not always believe what you skim. This is because people with a specific ideology can slant information by inundating the marketplace with their ideas or overwriting the ideas of others.

For example, prolific Wikipedia contributor Bryan Henderson, who goes by the name of “Giraffedata,” took it upon himself to eradicate use of the term “comprised of” from user-generated content on the popular information site.3 Over the course of eight years, Giraffedata removed the term more than 47,000 times in user postings.

Was this a grammatically sound move? Arguably, yes. But the fact that the “error” was made in more than 47,000 posts (and counting) speaks to the fact that the use of “comprised of” is common and acceptable.

Details

- Pages

- X, 240

- Publication Year

- 2023

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781636671017

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781636671024

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781636671000

- DOI

- 10.3726/b20561

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2016 (March)

- Keywords

- Mass communication information literacy media technology community Digital identity ideology democracy journalism Media literacy digital literacy world wide web school, family digital information

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Oxford, Wien, 2023. X, 240 pp., 19 b/w ill.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG