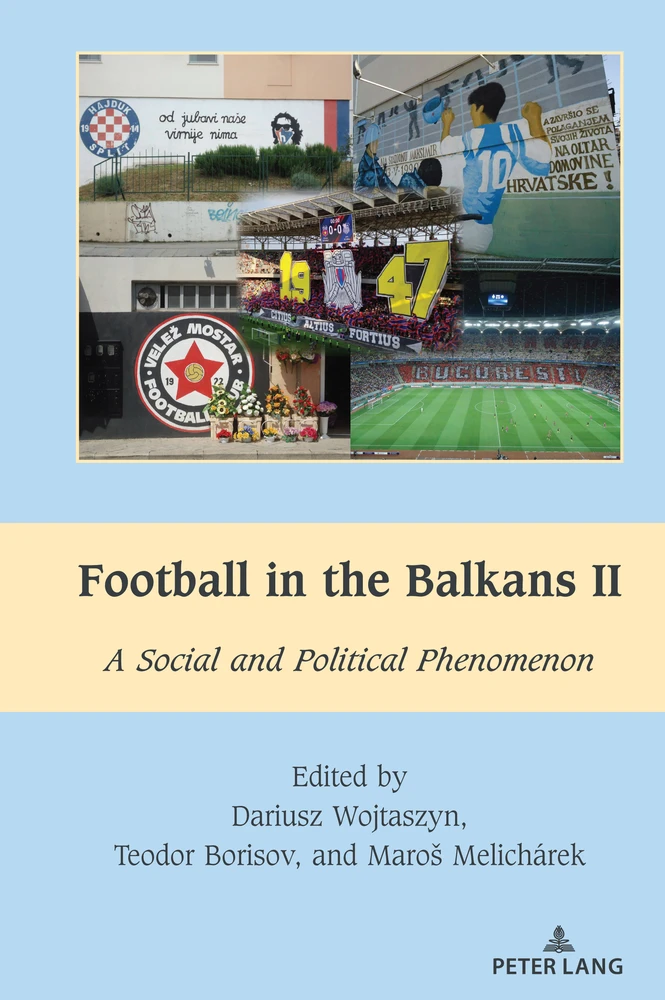

Football in the Balkans II

A Social and Political Phenomenon

Summary

The book complements and is a thematic development of the issues raised in the volume Football in the Balkans I: Internal Views, External Perceptions (Peter Lang, 2023). Both volumes present the interplay between sport and politics and the shaping of sport policy in the Balkan countries. This is a project initiated by the Balkan History Association and carried out in cooperation with the Centre for Research on the History of German and European Sport of the Willy Brandt Centre at the University of Wrocław in Poland.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Introduction: Football as a Social and Political Phenomenon in the Balkans—Local Specificity

- Between Collaboration and Tension: Balkan Football Teams in the Mitropa Cup

- A Haven from the War: Slovenian Football During Occupation (1941–1945)

- The People’s Republic of Bulgaria and Its Football through the Eyes of the West

- Football Culture and Public Memory: The Drone and Banner Incident and Transnational Memory Debates in the Balkans

- The Whole Neighborhood Was Breathing Steaua: The Urban Dynamics of Bucharest’s Fan Entourages

- Jel’ igraju naši? Football, Identity, and Nationalism in Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Orbán Goes to the Balkans: How Does the Support of Hungarian Government Affect Club Football in Neighboring Countries?

- North Macedonia Goes to Euro 2020: Football and the Ethnic “Other” on Social Media

- Conclusion

- Notes on Contributors

- Index

Preface

Richard Mills

The year 2024 marks the thirtieth anniversary of contrasting events in the history of football on the Balkan Peninsula. While national teams and players from the eastern Balkans experienced a golden age three decades ago, football in the war-torn west of the peninsula was internationally isolated and territorially riven. Yet, even there, play continued.

Over 90,000 spectators packed into Pasadena’s Rose Bowl stadium to witness Romania’s group stage victory over 1994 World Cup hosts the USA. Having topped the group, the Romanians overcame Argentina in the round of sixteen, before bowing out on penalties in the quarterfinals. Neighboring Bulgaria had an even more successful tournament, with victories over Argentina, Mexico, and defending champions Germany on their way to the semi-finals and a fourth-place finish. The USA94 “All-Star Eleven” featured Romania’s Gheorghe Hagi and Bulgarian teammates Krasimir Balakov and Hristo Stoichkov, the latter ending the tournament as joint top-scorer. Stoichkov also took the Ballon D’Or in 1994, a year when fellow World Cup star Hagi joined him at FC Barcelona. It was a summer that thrust these post-socialist countries on the Black Sea’s western shores into football’s global limelight.

The contrast with developments on the western, Adriatic, side of the peninsula could not have been starker. As Diana Ross opened the feel-good USA94 tournament with her comically inaccurate ceremonial penalty kick, the inhabitants of the former Yugoslavia had already endured three years of devastating conflict. The Yugoslav national team had been expelled from the international stage and the domestic football landscape shattered by the disintegration of the federal state and its sporting competitions. Nevertheless, the game stoically endured in the most difficult circumstances. In Bosnia and Hercegovina, an ongoing complex civil war resulted in the evolution of three distinct “national” competitions in 1994. In Bosnian government-held territory, Čelik Zenica won the inaugural Championship of Bosnia and Hercegovina, having hosted a makeshift final tournament under irregular wartime conditions. In Bosnian Serb territory, a fraught logistical situation made it impossible to hold a league championship in 1994, but Kozara Gradiška lifted the Republika Srpska Cup as part of celebrations to honor the Republika Srpska Army. Not to be outdone, the short-lived Bosnian Croat entity staged its own Football Championship of Herceg-Bosna, won by Mladost Široki Brijeg. Neither did the carnage of war prevent Bosnian footballers from appearing on the international stage, albeit in unconventional ways. In spring 1994, FK Sarajevo returned from a 12-month tour of Europe and Asia, where they raised awareness of the plight of their besieged city. In one of the more astonishing moments of the lengthy siege, some fifteen thousand Sarajevans took advantage of a ceasefire to watch a match between a city representation and a team of UN peacekeepers. It was a world away from the glitz and glamour of the Pasadena Rose Bowl, but even here football enabled players and fans a brief moment of respite.

In war-weary neighboring Croatia, the game thrived on either side of tense battlelines. The ailing breakaway Croatian Serb state of Republika Srpska Krajina—which would disappear from the map just a year later—held its own competitions in 1994, culminating with state president Milan Martić presenting the RSK Cup to victors Bukovica Kistanje. In the territories under Zagreb’s control, Croatian football was doing its best to rebuild, although the fact that strategically vital transport links remained severed by the separatist entity meant that the young republic’s clubs had to take lengthy detours by road and sea to compete in domestic competitions. UN sanctions against the much-diminished Federal Republic of Yugoslavia barred Serbia’s football giants from European football—including 1991 continental champions Red Star Belgrade—but Croatian sides had been readmitted for the 1993–1994 season. This enabled Hajduk Split to shine on the European stage, as they reached the quarterfinals of the 1994–1995 UEFA Champions League. Indeed, the group stage of that competition suggested that the region’s clubs had a bright future. Alongside Hajduk, the Balkan contingent consisted of Galatasaray, 1986 winners Steaua Bucharest, and AEK Athens.

Thirty years on, the football landscape of the Balkans is transformed. Romania and Bulgaria, the powerhouses of 1994, have failed to qualify for the World Cup for over 25 years. By contrast, the countries of the former Yugoslavia have made a combined total of 14 appearances at the finals between 1998 and 2022, providing two qualifiers for every edition of the World Cup. Most striking of all are the feats of the Croatian national team. Representing a young country of under four million inhabitants, Croatia’s footballers made an astonishing run to the World Cup Final in Russia, a feat sandwiched between impressive third-place finishes in 1998 and 2022. Elsewhere, Greece provided one of the shocks of European Championship history, returning to the 2004 tournament after a lengthy absence and winning it as a rank outsider. Turkey, a footballing power that had been absent from the World Cup finals for over four decades, provided another shock by finishing third at the 2002 World Cup and followed this up with another third-place finish at the 2008 European Championship. Yet, club sides from the Balkans have struggled in European competitions over the last three decades, rarely reaching the latter stages. Galatasaray—based on the Balkan west bank of the Bosporus strait which divides the Turkish largest city—are a rare exception, having lifted the UEFA Cup in 2000.

Domestically, club football across the region has struggled in the face of economic hardship, corruption, legal scandals, and the constant exodus of talent to more affluent leagues. Political and financial transitions which began in the late-1980s have culminated in pitched battles over the ownership and identities of such storied clubs as Steaua Bucharest and CSKA Sofia, but also of lesser-known sides like Kosovo’s FK Trepça/FK Trepča. This has generated national league tables featuring multiple iterations of the same club, with contested claims to the legacies of their socialist-era forebears. A sad continuity throughout the decades in question have been the deadly bouts of hooligan violence and nationalist outbursts that have scarred the game across the region. Most recently, we have witnessed the fatal stabbing of an AEK Athens fan during violent clashes involving visiting Dinamo Zagreb ultras in August 2023, and a physical assault by a Turkish Süper Lig club president on referee Halil Umut Meler, which triggered the Turkish Football Federation to temporarily suspend all league football in December 2023. Other major developments over the last three decades have included the turbulent reintegration of league football in post-war Bosnia and Hercegovina, the controversial recognition of Kosovo by UEFA and FIFA, and the steady development of the women’s game throughout the region. The same period has seen the peninsula capture international attention in other ways. The erection of state-of-the-art stadiums in Balkan capitals (though the countries of the former Yugoslavia are notable exceptions in this regard) has attracted multiple European finals to the peninsula. Most recently, Bucharest staged matches of the delayed UEFA Euro 2020 tournament, Istanbul hosted the 2023 Champions League Final, and the Albanian capital Tirana welcomed the inaugural UEFA Conference League Final in 2022.

Ever since the first leather ball rolled into the Balkan Peninsula, the game has been at the forefront of social and political developments. Consequently, the region’s football landscape has attracted growing academic interest over the last three decades. In the intriguing collection of essays that follows, editors Teodor Borisov, Maroš Melichárek, and Dariusz Wojtaszyn offer readers new insights from talented and innovative researchers based at universities across the continent. In combination, they shed light on a tantalizing array of historical and contemporary developments. With the game as fluid now as it was back in 1994, this is an opportune time to subject Balkan football to another round of scrutiny.

Introduction: Football as a Social and Political Phenomenon in the Balkans—Local Specificity

Teodor Borisov, Maroš Melichárek, and Dariusz Wojtaszyn

It has a lot of power to change things in life, not just my life, but in wider society. Football brings everyone together, it brings smiles to people’s faces, it brings races together and more.

Football is a symbol that means that everyone can, at the same time, compete and live together.

Louis Saha—a French former professional footballer (quoted in Shah, 2023)

Social sciences focusing on nationalism and identity generally recognize that sports constitute a significant ritual within popular culture and contribute to the theoretical concept of the nation as an “imagined community” (Cooley and Brentin, 2016). Scholars from various disciplines agree that sports hold social, cultural, and political significance in the formation of collective identity at local, national, regional, and global levels. The utilization and orientation of football, in particular, have often served specific political, social, or economic objectives. Due to its growing potential for social impact and its pervasive nature, football has been closely linked to the political and economic spheres. Consequently, political leaders have sought to harness football to achieve or promote their own goals (Melicharek and Wojtaszyn, 2023, 4). Suffice it to mention the successes of the Italian national team during Benito Mussolini’s regime or the way the military junta used Argentina’s success at the 1978 World Cup. However, the relative transparency of the game itself has not always led to the anticipated outcomes in terms of propagandistic or ideological aims.

Any human involvement in sport is a complicated and complex social phenomenon, requiring not only careful analysis but a recognition of the limitations inherent from any one perspective. No single perspective can encapsulate the whole of any social phenomenon (Finn, 1994, 87). We may assume that sociological thinking contributes to a better understanding of the role of sport in society. The social roots of football have long been established, and across the world, football’s culture, heritage, and identity are entrenched within local communities. It is the synergy between football’s local and global appeal, its reach and subsequent responsibility and indebtedness to its communities that we must capitalize on, in order to ensure that football can act as a vehicle for the promotion of social good for all (Weiss and Norden, 2021, 15; Parnell and Richardson, 2017, 1). The fact that there are more FIFA member countries than are in the United Nations (211 vs. 193) is indicative of the international reach of The Beautiful Game and its social significance.

The game’s autonomous character has also posed a threat to dictatorships that have attempted to organize and ideologically monopolize people’s leisure time, as football has served as a means of mitigating the constant mobilization of the masses (Koller and Brandle, 2015, 200). The intensity of ethnic and nationalist sentiments in the Balkans, coupled with the significance of sports in the region, makes the post-Yugoslav space a natural laboratory for researching the close interconnection between sports, religion, ethnicity, and nationalism (Brentin, 2013, 993). Research on the intersection of politics, ideologies, and football illustrates the dynamic path by which football is engaged in the creation of collective identities, communities, and globalization (Spaaij et al., 2018, 6; Benedikter and Wojtaszyn, 2020). The academic debate concerning the link between international politics and modern sports demonstrates that separating these two phenomena is neither feasible nor acceptable. The ideological flexibility of sports as a social sphere is best exemplified by a statement made by the renowned scholar of sports and politics, John Haberman: “Sport can serve any ideology” (Brentin and Zec, 2017).

This volume will go into the history of football and its role in society in the Balkans. The book will contribute to a nuanced understanding of football as a multifaceted cultural phenomenon in the Balkans, illustrating its entanglement with politics, identity, nationalism, and regional dynamics. Special attention has been paid to the following main issues: the political background of football over the years, the formation and development of fan culture, the importance of football for different social groups and nationalities, the cultural framework of football, and the impact of football on international relations. Each chapter offers a unique perspective on the intricate relationship between football and the broader socio-cultural landscape in the Balkan region. The volume reaches far beyond the Balkans in terms of geography, politics, and social issues. This book is a thematic development of the issues raised in Volume I, Football in the Balkans: Internal Views, External Perceptions. It is also complementary in territorial terms—the following countries are included in this volume, along with their impact on the Balkan states: Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Kosovo, North Macedonia, Romania, Serbia, Slovenia, and Hungary. Both volumes present the interplay between sport and politics and the shaping of sports policy in the Balkan countries. Achievement of the stated objectives was effected through an interdisciplinary approach. The authors used a broad spectrum of interdisciplinary, subject-specific research methods—from classical historiographical approaches through sociological and cultural studies to issues related to economics.

Individual chapters offer a view on the football in the Balkans from a broader or higher perspective; for example, the chapter by Dariusz Wojtaszyn and Lorenzo Venuti, “Between Collaboration and Tension: Balkan Football Teams in the Mitropa Cup,” reveals how sports serve as a platform for regional interactions and competitions, mirroring the broader geopolitical context. The Mitropa Cup overreached the Balkan region and became a European phenomenon.

Details

- Pages

- X, 224

- Publication Year

- 2024

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781636676067

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781636676074

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781636676050

- DOI

- 10.3726/b21126

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2024 (November)

- Keywords

- Football Balkans Politics Supporters Romania National Identity Communism

- Published

- New York, Berlin, Bruxelles, Chennai, Lausanne, Oxford, 2024. X, 224 pp. 5 b/w ill., 3 b/w tables.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG