‘VAT Gap’ in Poland: Policy Problem and Policy Response

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1. Gauging the depth of the crisis – The Polish ‘VAT gap’ evolution

- Chapter 2. Intra-community transactions involving Poland in the mirror statistic data

- Chapter 3. Noticing the VAT compliance crisis: The analysis of VAT-related Parliamentary speeches

- Chapter 4. Policy response – Tax administration activities

- Chapter 5. Policy response – Legislative initiatives in the area of tax law

- Chapter 6. Criminal policy response - Motives for criminalisation and the statistical picture

- Chapter 7. Criminal policy response - Case files research

Dominik J. Gajewski (SGH Warsaw School of Economics)

Introduction

In the European Union (EU) – as well as in many other jurisdictions1, Value Added Tax (VAT) constitutes the backbone of the tax system, raising substantial part of the tax revenues2.

The key strength attributed to VAT is neutrality to the economic processes (contrary to, say income taxation). Levied on the value added at subsequent steps of production chain, it is collected fractionally, via a system of partial payments and deductions (or reclaims). In other words, businesses collect VAT from buyers of their products, and deduct VAT they paid themselves at earlier stages of the production chain, buying, for example, raw materials or business services.

Due to its design, it is hardly surprising that VAT was also the first tax harmonized within the EU (in subsequent so called ‘VAT directives’3). ‘It was evident that if there was ever going to be an efficient, single market in Europe, a neutral and transparent turnover tax system was required which ensured tax neutrality and allowed the exact amount of tax to be rebated at the point of export’.4 Moreover, Council Decision 70/243 of April 21 1970, established VAT-based system for financing the EU budget.

VAT harmonization had been an important step in establishing the EU-wide Single Market, design for value creation chains spanning from one Member State to another – as illustrated by successful airplane manufacturer Airbus. On the other hand, the tax collection remained in the hands of Member State administrative apparatus. Thereby the key problem surfaced – maintaining VAT neutrality at the points of import/export from one Member State to Another.

The solution – rules for taxing Intra-Community delivery and Intra-Community acquisition – turned out a threat to the whole harmonized VAT system, as it created an opportunity for so called ‘Missing Trader Intra Community fraud’ (MTIC fraud). Its most elaborated form, so called ‘carousel fraud’ – based on artificial movement of goods (or just invoices) in a circle involving repeated Intra-Community deliveries and acquisitions – provided organized crime with financial perpetuum mobile, powered by taxpayers money extorted as undue VAT reclaims.

Coupled with more traditional forms of tax evasion, known also in sales tax systems (like sells underreporting as well as total or partial operation in so called ‘shadow economy’), MTIC frauds represented forms of VAT noncompliance – leading to the loss of state revenues.

Macroeconomic attempt to proxy these losses is the concept of so called ‘VAT gap’ (also referred to as a ‘compliance gap’),broadly defined as the difference between the total amounts of theoretically collectable VAT (as based on the applicable tax law) and the total amounts of VAT actually collected in a given period (see Chapter 1).

The concept of ‘tax gaps’ – the rough indicators of tax revenue loss gained widespread attention among scholars and policymakers in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. The problems were essentially foresaw by the International Monetary Fund, who warned domestic authorities that ‘with the economic downturn, tax agencies are encountering growing compliance risks’ as ‘an economic downturn tends to worsen taxpayer compliance in important aspects’5. Specifically, it warned that crisis could shift in economic activity from the formal (taxed) sector to the so called ‘shadow economy’ (studies like e.g. Mai, Schneider6 provided evidences confirming that prediction).

Although the Global Financial Crisis starting in 2008 – and the Eurozone Sovereign Debt Crisis erupting few years later – constitute important part of the VAT noncompliance story, the state capacity and the policy choices are another important factor.

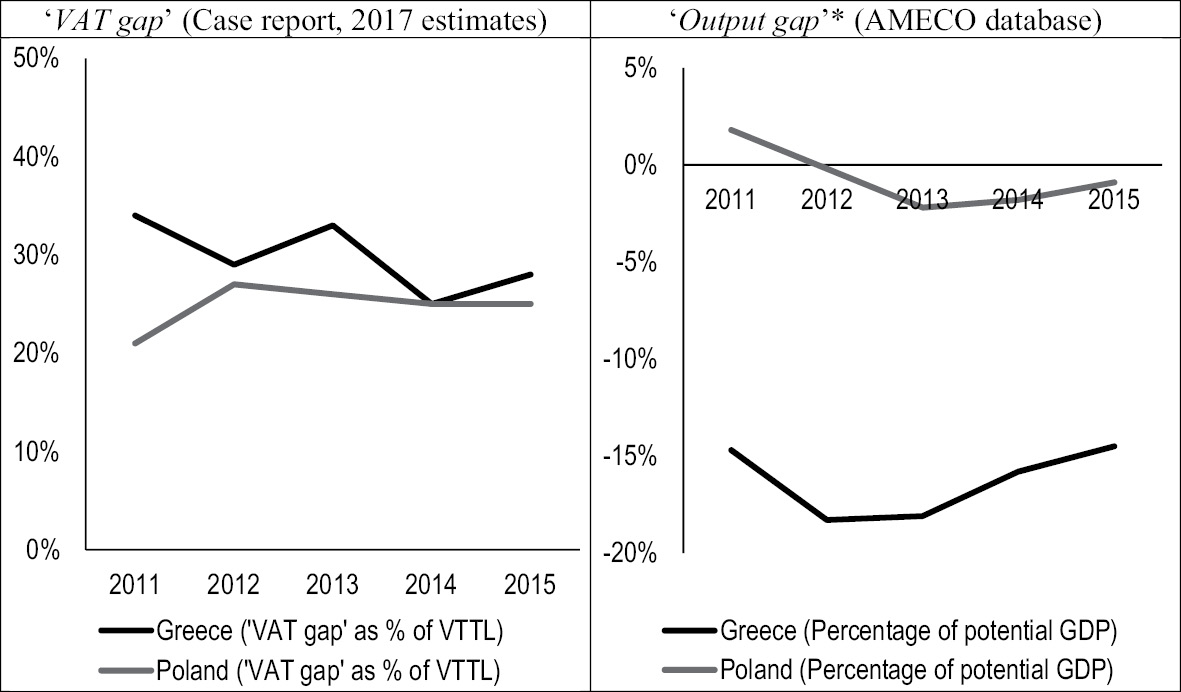

That is particularly true as far as Polish VAT compliance crisis is concerned. Despite the fact that Poland have not experienced recession after Financial and Eurozone crises, the size of its ‘VAT gap’ almost reached the levels recorded by Greece – the hardest hit EU Member State (see Figure I.1.). Thereby, growth in its ‘VAT gap’ could not be simply dismissed as a consequence of cyclical downturns.

Figure I.1.Comparison of VAT noncompliance (‘VAT gap’, left panel) and business cycle (‘Output gap’, right panel) of Poland and Greece

*- Gap between actual GDP and potential GDP, percentage of potential GDP (AVGDGP)

Source: ‘VAT gap’ – European Commission, 2017; ‘Output gap’ – AMECO Online (Current Version 2023-05-15 11:00)

Given the popularity and importance of VAT in the EU and overseas, in depth examination of Polish noncompliance crisis is important for both the scholars and policymakers. The goal of this book is to examined it from the policy-making perspective. It depicts the state apparatus as facing red flags, indicating the problem, struggling to grasp its importance and underlying mechanics – and to develop and implement policies.

Noteworthy, the VAT noncompliance problem cut across traditional realms of legal scholarship (tax law, fiscal-criminal law, criminal law) and state apparatus organization (tax administration, crime control apparatus). Thereby, developing effective policy requires substantial coordination effort. The very same is true as far as scientific inquiry is concerned.

As a consequence, this book had been organized into two broad thematic blocks.

The first one deals with the overall description of ‘VAT gap’ crisis, and includes first three chapters. It illuminates the process of learning about the compliance crisis, with emphasize on various macro-level indicators available to the decision-makers, and the narratives formed to make sense of these evidence.

The second part deals with the activities undertook, in order to handle the crisis. They had been divided into three broad areas, covered in the subsequent chapters. The starting point is the response form broadly defined tax administration apparatus – the first line of the defence against VAT frauds and the migration of the economic activity to the ‘shadow economy’. The reshuffling of tax administration apparatus, carried out in 2017 in order to improve its effectiveness in countering VAT fraud was described, together with two groups of control activities. The backward-looking controls aimed at spotting past noncompliance in an attempt to establish and recover VAT liability – as well as real-time activities like blocking fraudulent VAT reclaims, to prevent budget losses at the first place.

Then, the legislative response in the area of tax law is examined, with focus on key instruments implemented by the lawmakers in order to curb VAT noncompliance. The earliest instruments were discussed, together with later, wholesale, economy-wide interventions like so called Single Control File (Polish JPK).

Finally, the legislative response in the area of criminal law was examined, with focus on the severe sanctions introduced for issuing so called ‘empty invoices’ – the necessarily component of ‘MTIC’ fraud (as well as less sophisticated fraudulent activities).

While this book aims at the description of the policy response to the problem of Polish VAT noncompliance, as gauged by expanding ‘VAT gap’ over 2011–2016 period, it is not sort of authoritative inquiry into the causes of the crisis, its chronologies, nor a political exercise in blame-game. Also, there are reasons to believe, that fight against the VAT frauds is not finished yet, thereby it is still to early for an authoritative history of the crisis.

To this day voluminous materials had been assembled in order to allocate the blame for the crisis, trace its dynamics and – sometimes – outline lessons learned. Interested reader could consult:

- The report of the Parliamentary Investigative Committee (with separate opinion and numerous appendices);

- The Supreme Audit Office (Polish: NIK) reports for VAT-related audits;

- The Polish Economic Institute (Polish: PIE) report;

- Series of English-language UN Global Compact reports on ‘shadow economy’ in Poland.

1 For map of worldwide VAT application see: https://www.imf.org/external/np/fad/tpaf/pages/vat.htm (Accessed Oct. 31, 2023)

2 This monography is the result of scientific research carried out as part of the grant from the National Science Centre on ‘Vat Gap in Poland: Policy Problem and Policy Response’ – OPUS 16 (No. 2018/31/B/HS5/00234).

3 The key milestones involved: First Council Directive 67/227/EEC of 11 April 1967 on the harmonisation of legislation of Member States concerning turnover taxes; Sixth Council Directive 77/388/EEC of 17 May 1977 on the harmonization of the laws of the Member States relating to turnover taxes – Common system of value added tax: uniform basis of assessment; Council Directive 2006/112/EC of 28 November 2006.

Details

- Pages

- 180

- Publication Year

- 2024

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783631916407

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783631916414

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783631908747

- DOI

- 10.3726/b21666

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2024 (March)

- Keywords

- tax law VAT VAT Gap Tax Policy tax avoidance tax evasion

- Published

- Berlin, Bruxelles, Chennai, Lausanne, New York, Oxford, 2024. 180 pp.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG