Irish in Outlook

A Hundred Years of Irish Education

Summary

This collection of essays explores the centrality of the Irish language and the desired «Irish outlook» in education, touching on key developments within Irish language education, educational policy and the role of Irish in society over the past hundred years.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part I A Hundred Years of Revitalisation and Irish-Language Education

- Solas sa Dorchadas: An tAthair Eoghan Ó Gramhnaigh agus Coláiste Phádraig, Maigh Nuad

- Remembering, Misremembering and Forgetting: The Early Periods in the Teaching of Irish

- Ról an Oideachais san Athneartú Teanga: Súil Siar, Féidearthachtaí agus Dúshláin Reatha

- Buntús Gaeilge (1966) and Its Aftermath

- An Scéalaí: Foghlaim (Ríomhchuidithe) na Gaeilge

- Part II Policy and Ideology in Education

- From Subordinate to Pre-eminent: Irish Language Curriculum Policy for Primary Schools in the 1920s

- The Foundation of the Preparatory Colleges and Their Ideological Mission in the Irish Free State, 1922–1937

- ‘Ar aon chéim le aon phobal fud fad na tíre, fud fad an domhain’: The Gaelscoil Movement during the Late Twentieth Century and Implicit/Explicit Decolonial Ideology

- The Purpose of Irish History in Secondary Schools, 1924–1969

- Part III Gaelicising Reading, Writing, and Publishing

- A Great Dearth of Irish Books and How An Gúm Bridged the Gap

- Comhaid an Ghúim agus na hAistriúcháin don Aos Óg, 1926–1951

- Gaelicisation, Education, and the cló Gaelach

- Conclusion

- Notes on Contributors

- Index

Tables

Table 6.1:Qualifications in Irish of all teachers serving in national schools 1924–1960

Acknowledgements

This volume would not have been completed without the support of several colleagues and institutions. First and foremost, I wish to thank the School of Education, Trinity College Dublin, and Marino Institute of Education for hosting the centenary conference ‘Irish in Outlook’, held in Trinity in May 2022, which gave rise to this volume. Special thanks are due to Head of School, Carmel O’Sullivan, for her enthusiasm when the project was first proposed and for agreeing to sponsor the conference, and also to the Cultures, Academic Values and Education Research Centre (CAVE) for sponsoring both the conference and the production of this volume. We are grateful to our two keynote speakers, Professor Teresa O’Doherty and Professor Muiris Ó Laoire for their insightful and engaging keynote speeches. In addition, the authors wish to thank those present at the time for their generous feedback and lively discussion, much of which has no doubt filtered into this volume.

Some of the contributions contained in this volume have also benefited from individual streams of research funding. Claire M. Dunne and Kerron Ó Luain wish to acknowledge An Chomhairle um Oideachas Gaeltachta agus Gaelscolaíochta for their support in undertaking their research. Nicole Volmering wishes to gratefully acknowledge that the research conducted in this publication was in part funded by the Irish Research Council under grant number 21/PATH-A/9465.

Finally, the editors wish to thank the reviewers and readers who gave their valuable time to read and comment on the essays in this volume and of course the editorial team at Peter Lang, whose enthusiasm, advice and patience is greatly appreciated.

Nicole Volmering

Introduction

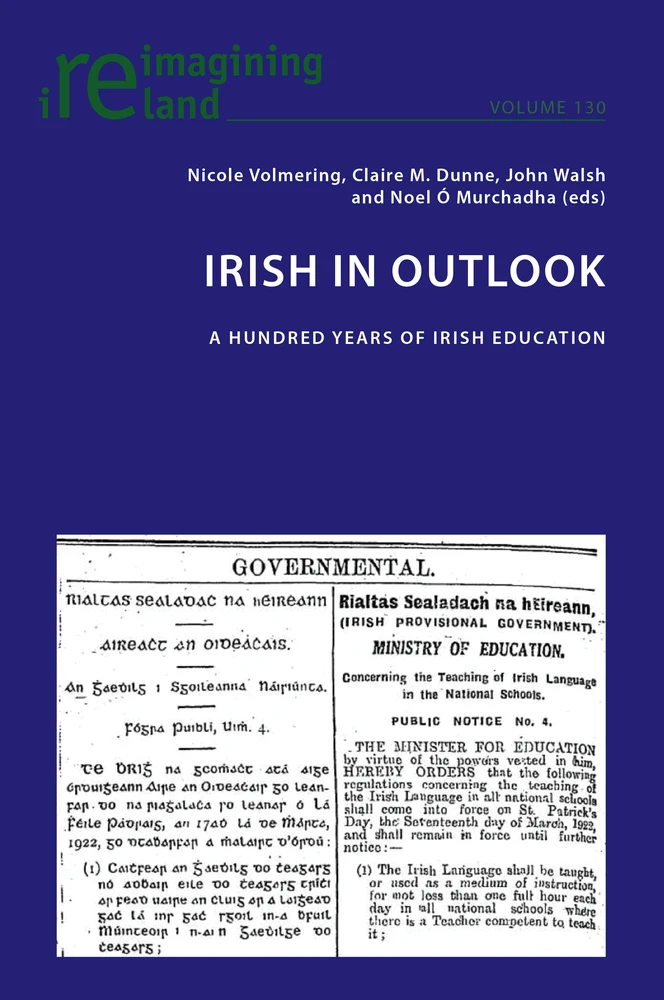

This volume marks the 2022 centenary of the publication of Public Notice No. 4 ‘Concerning the Teaching of Irish Language in the National Schools’, issued on 1 February 1922, and the creation of the first National Programme for education in the Saorstát. Central to the outlook of the educational programme of the new State was the position of the Irish language as a marker of Irish national identity and culture. The Provisional Government was keen to implement a programme of Gaelicisation which would highlight Ireland’s cultural independence from England and revitalise the language and cultural nationalism eroded through years of Anglicisation. This principal aim had far-reaching consequences for both the shape of the education system itself and its educational programme, as well as for the survival and pedagogy of Irish into the twenty-first century. With the creation of this new strategy for education in the 1920s, the incumbent Government set the tone for an education system heavily shaped by the political events and revivalist ideology of that era, which would remain largely unaltered for the next forty years. In line with the priorities of a government looking ahead to a post-colonial future, education was first and foremost seen as a means towards Gaelicisation.

The project of Gaelicisation was principally, if not exclusively, centred on revitalisation of the language. The view that the education system would be the primary vehicle for affecting this change informed radical changes and key policy decisions in this area, such as the creation of the preparatory colleges (see Chapters 6 and 7) and Irish-medium infant classes. The nationalist character of the First and Second National Programme for Primary Instruction, and the centrality of the Irish language within the educational system more broadly, built on the earlier work of the revivalist movement (see further Ó Laoire, Chapter 3). The work of societies such as the Gaelic League (founded 1893) and the work of individuals such as Eoghan Ó Gramhnaigh, Eoin Mac Néill and Pádraig Mac Piarais created a fertile environment for the development of pedagogical approaches to the teaching of Irish, both in the classroom and outside it. Although in some ways, the Programme was an extension of the programme of formal language teaching initiated by the Gaelic League, in other ways, it arose out of a vacuum. After decades of neglect of Irish history, language and literature under British rule, during which the teaching of Irish was only permitted outside school hours (from 1878) or as an aid to learning English (from 1883), bilingual education in Gaeltacht areas had only been formalised in 1904 under the Bilingual Programme. While these concessions represented a great success for the Gaelic League, by 1920 still only about 22 per cent of all primary schools offered a form of Irish-language education. Nevertheless, the First National Programme for Primary Instruction (1922) and subsequently the revised Second National Programme (1926) formally consolidated the centrality of Irish as well as the ‘Irish Outlook’ of education in the State within the educational programme itself. Alongside the language, Irish history and literature were now also given a place in the curriculum. The practical direct and indirect implications of this seismic policy shift, which reverberated far beyond the classroom, are explored in detail in this volume.

The history of Gaelicisation in education is closely tied to the nation’s evolving political and ideological identity, which is mirrored in the self-image created through the teaching of its history (see Mac Gearailt, Chapter 9) and through shifts in emphasis in the organisation of its educational system (e.g. Ó Luain, Chapter 8). This is where the close relationship between language and nationhood in Irish cultural nationalism comes to the fore – a theme that surfaces in many of the contributions in this volume. The 1922 Irish curriculum, proclaimed as ‘a new starting point in the history of primary education in Ireland’, was expected to be ‘Irish in outlook’, and emphasised citizenship and locality (Ó Brolcháin 1922). It gave prominence to Irish history and geography and stressed that the purpose of teaching history should be ‘to develop the best traits of the national character and to inculcate national pride and self-respect’ (First National Programme 1922). With so much emphasis traditionally placed on the Irish language, it is easy to overlook that with the project of Gaelicisation also came a burgeoning post-colonial Europeanism that asked for a repositioning of the nation’s ‘outlook’ in more than one way. Thus, along with the emphasis on Irish national cultural strengths came the observation that English had only a ‘limited place […] among all the European literatures’, and that reading in English ‘should be mainly directed to the works of European authors’ (First National Programme 1922). This shift in emphasis is one of many ways in which the education system was explicitly decolonial (see Ó Luain, Chapter 8).

While policy shifted in the 1960s and 1970s, where the role of the language in education was concerned, Gaelicisation has remained a major factor in the history of state-sponsored education even to this day. The focus, however, graduated towards restoration of the language as a medium of communication in the community as well as in schools, stimulating its flourishing within a bilingual (if predominantly English-speaking) society (Government of Ireland 1965). In 1960, then Minister for Education, Patrick Hillery, announced that junior classes in English-speaking schools would no longer have to be taught through the medium of Irish. Ironically, this perceived ‘loosening’ of the central role of education in the Gaelicisation programme, of which Hillery was accused, stimulated the grassroots development of the Gaelscoileanna (see Ó Luain, Chapter 8). Under the same Minister, a commission on the restoration of the Irish language had been appointed, which would ultimately lead to a research-based course of instruction, Buntús Cainte (see Hyland, Chapter 4), accessible to the wider public.

In the early years, however, the creation of resources for teaching posed serious practical challenges, many of which were only gradually resolved as successive governments struggled to come to grips with the implementation of its policies. The lack of suitable schoolbooks led to the foundation of a state-sponsored publishing house, An Gúm (see Uí Laighléis and Nic Lochlainn, Chapters 10 and 11), tasked with producing both suitable textbooks and translations for general readers. The practical challenges of printing suitable books, both in terms of content and typeface, exposed the, perhaps unforeseen, difficulties faced by the government in implementing its policy. Attempts to standardise the printing of Irish in particular were intimately tied up with the debate surrounding the typeface (should Irish be written in Irish or Roman script?) and the challenge of standardising spelling and grammar – both issues which, in their own right, were closely intertwined with perceptions of cultural nationalism (see Volmering, Chapter 12). More considerable, however, was the lack of teachers competent in Irish at the time of the implementation of the new Programme. To accommodate, the government made the radical decision to create dedicated teacher training colleges and preparatory colleges, with the specific purpose of producing teachers competent in Irish (see Chapters 6 and 7). Thus, despite the fact that the government never managed to achieve its initial goal of restoring a primarily Irish-speaking Ireland through education, Gaelicisation did give rise to significant innovation in formal education, in the pedagogy of Irish and history and in the area of printing. Not all of the measures taken at the turn of the century would prove successful or long-lasting, but innovation continued in other ways in later years, with the publication of Buntús Cainte and the rise of the Gaelscoileanna. The teaching of Irish has since further benefited from technological developments. The platform An Scéalai, for instance, discussed in Chapter 5 of this volume (Ní Chiaráin), is a digital educational resource informed by linguistics research designed to better meet the needs of modern students, whether learning within the classroom or pursuing self-directed study.

***

Effective as of St Patrick’s day, 1922, the Provisional Government placed Irishness and the Irish language at the centre of its vision for education in the Free State. To reflect on this momentous change in Irish education and its long-lasting impact, this collection of essays explores the centrality of the Irish language and the desired ‘Irish outlook’ in education, training, and policy as well as its indirect influence on associated printing and the development of language pedagogy. Broadly, this bilingual volume targets the intersection between education and the politics of Gaelicisation and cultural nationalism, touching on key developments within Irish language education, educational policy and practice over the past hundred years, as well as the legacies of key historical figures and policies for the present. As Claire M. Dunne writes elsewhere in this volume, historical assessments of the early periods in the teaching of Irish often focus on the weaknesses experienced by teachers and learners because of new governmental policy. Some of this criticism is certainly also represented in this volume. However, in taking a wide vantage point, it also highlights impact on contiguous areas such as printing and writing, on the subsequent development of Irish-language pedagogy, and on the continued debate around the role of Irish in society and the role of education in revitalising and promoting the language. While addressing common themes, the volume brings together experts in adjoining disciplines with diverse perspectives on the topic. In the interest of providing a rich volume, the individual studies present complementary analyses and interpretations of related questions. The views expressed in the collection do not necessarily reflect the views of the editors; rather, we have left room for intersecting and disparate voices and it is hoped that this volume will stimulate further discussion and research relevant to Irish education past and present.

The volume is divided into three parts, reflecting key areas of development: Irish-language revitalisation and education, educational policy and ideology, and the impact of Gaelicisation on print. Part I probes a theme as central to the creation of the educational programme in the State as to the hundred years following, that of the relationship between language revitalisation and Irish-language education. This section of the volume examines both pivotal and under-represented moments in the last hundred years of language education. Tracey Ní Mhaonaigh details the early and significant efforts of Eugene O’Growney (d. 1899) to promote the Irish language both within St Patrick’s College, Maynooth, and outside it, and create some of the earliest public resources for its study. Claire M. Dunne highlights gaps in our collective cultural memory of the teaching of Irish in the early years of the Free State, particularly where it concerns the creative classroom experiences and writings of women. Muiris Ó Laoire reviews the role of primary education in Irish language revitalisation at the start of the twentieth century and today, considering whether education alone can meet the challenges of revitalising the living language. Moving into the second half of the century, Áine Hyland describes the innovative research undertaken by Tomás Ó Domhnalláin and his colleagues as part of Buntús Gaeilge. This work would ultimately lead to the publication of one of the most popular Irish courses ever produced, Buntús Cainte. Finally, Neasa Ní Chiaráin introduces the computer-assisted language learning platform, An Scéalaí, which is informed by her research on speech technologies for Irish, and which is suitable for self-directed learners as well as school-based learning.

Part II explores the considerable importance of the connection between policy and ideology in the formation of the national education system. This part opens with an essay in which Tom Walsh considers the circumstances around the publication of Public Notice No. 4 and the creation of the first and second national programmes of education, with particular attention to the influence of the national programme conferences and the Rev. Professor Timothy Corcoran SJ. John Walsh in turn explores the creation of the Preparatory Colleges; new, second-level, residential colleges designed to secure the Gaelicisation of the training colleges and underpin the government’s policy of reviving the national language through the schools. Kerron Ó Luain examines the rise of the Gaelscoil movement from the 1970s, when parents and activists stepped in to fill the vacuum of support created by the state’s policy shift, through a decolonial lens which reveals both explicit and implicit responses to the colonial past. Closing this section, Colm Mac Gearailt examines the connection between ideology and education by exploring the purpose of the teaching of history as a school subject, arguing that the subject was seen as means to promote citizenship and national identity.

Finally, Part III concerns the impact of Gaelicisation on reading, writing, and publishing. By far the most impactful measure taken by the government was the foundation of the publishing house An Gúm, which had responsibility for publishing Irish-language textbooks and literature as well as translations of other literatures into Irish, as discussed by Gearóidín Uí Laighléis and Caoimhe Nic Lochlainn. The work of An Gúm laid the foundations for a whole new generation of writers, editors and translators. Associated with the question of publication is also that of printing: Irish was printed both in Roman type and in the cló Gaelach or Irish type, but the choice of typeface was far from uncontentious, as discussed by the present author in Chapter 12, and the choice to abandon the cló Gaelach – together with the move towards standardisation of Irish spelling and grammar – inadvertently contributed to a sense of alienation from the language for some speakers.

References

- First National Programme of Primary Instruction. (1922/1987). In Á. Hyland and K. Milne (eds), Irish Educational Documents – Volume 1: Selection of Extracts from Documents Relating to the History of Irish Education from the Earliest Times to 1922, p. 94. Dublin: Church of Ireland College of Education.

- Government of Ireland. (1965). Athbheochan na Gaeilge: The Restoration of the Irish Language. Dublin: The Stationery Office.

- Ó Brolchain, P. (1922/1987). ‘Circular Dated April, 1922 [Accompanying the Programme of Instruction as Recommended by the First National Programme Conference]’. In Á. Hyland and K. Milne (eds), Irish Educational Documents – Volume 1, pp. 89–90. Dublin: Church of Ireland College of Education.

Details

- Pages

- XIV, 334

- Publication Year

- 2024

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781803741505

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781803741512

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781803740904

- DOI

- 10.3726/b20746

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2024 (September)

- Keywords

- Irish Education centrality of the Irish language Irish outlook educational policy Irish in society

- Published

- Oxford, Berlin, Bruxelles, Chennai, Lausanne, New York, 2024. XIV, 334 pp., 6 fig. b/w, 2 tables.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG