The Unbroken Covenant

Could Ulster Unionists have controlled a nine-county Northern Ireland, 1920-1945?

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

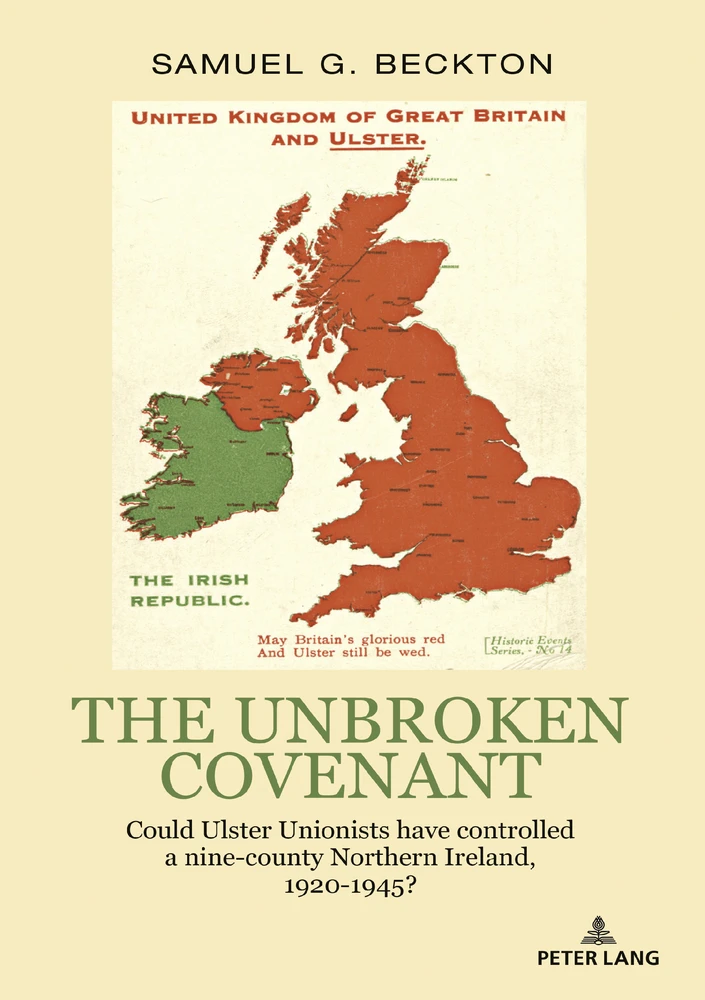

- Cover

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- List of Tables

- List of Figures

- List of Abbreviations

- Chapter 1 Introduction: Literature Review and Background

- Chapter 2 Establishment of Northern Ireland, 1920–1924

- Chapter 3 Irish Boundary Commission, 1924–1925

- Chapter 4 What We Have We Hold, 1926–1939

- Chapter 5 Ulster and the Second World War, 1939–1945

- Conclusion & Epilogue

- Appendix

- Bibliography

- Index

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my gratitude to many people and institutions for providing me assistance for this work. I would like to thank Dr Emmet O’Connor, School of Arts and Humanities, Ulster University; Adrian Kerr, Museum of Free Derry; Stewart Mclean, Project Orange and the Newtowncunningham Community Outreach Project; Jonathan Mattison, Museum of Orange Heritage; and Robert Love, for their advice and help.

This work would not have been accomplished without the help of staff from the following institutions: the British Library; Museum of Free Derry; National Library of Ireland; National Archives (UK); Public Records Office of Northern Ireland; and Museum of Orange Heritage.

Finally, and most importantly, I want to thank my family and friends for their continued encouragement. I would like to dedicate this work to my parents, Gary and Rita, who taught me the value of education and their support of my work.

Tables

Appendix 2: Representation of Nationalists in Unionist-held local councils

Figures

Figure 7: Wards for Clones Urban District Council based on the 1911 census

Figure 8: 1911 census of Clones Urban District Council and local townlands

Figure 9: Exchange of townlands in Monaghan

Figure 11: Revised Cavan County Council electoral divisions

Figure 13: Revised Monaghan County Council electoral divisions

Figure 16: North East Donegal County Council electoral divisions

Figure 17: Speculated Irish Boundary Commission recommendations, 1925

Abbreviations

County Cavan Grand Orange Lodge |

CCGOL |

County Donegal Grand Orange Lodge |

CDGOL |

County Monaghan Grand Orange Lodge |

CMGOL |

Deputy Lieutenant |

DL |

District Electoral Division |

DED |

First-Past-The-Post |

FPTP |

Grand Orange Lodge of Ireland |

GOLI |

Irish Parliamentary Party |

IPP |

Irish Republican Army |

IRA |

Local Electoral Area |

LEA |

Loyal Orange Lodge |

LOL |

National Health Service |

NHS |

North East Donegal County Council |

NEDCC |

Public Records Office of Northern Ireland |

PRONI |

Royal Irish Constabulary |

RIC |

Royal Ulster Constabulary |

RUC |

Rural District Council |

RDC |

Single Transferable Vote |

STV |

South West Donegal County Council |

SWDCC |

TD |

|

Ulster Special Constabulary |

USC |

UUC |

|

Ulster Unionist Party |

UUP |

Ulster Volunteer Force |

UVF |

United Kingdom |

UK |

United States of America |

USA |

Urban District Council |

UDC |

CHAPTER 1 Introduction: Literature Review and Background

If one were to live in or visit the city of Belfast, you would often be reminded of the province’s history, whether you wanted to be or not, with murals depicting many of these moments to remembered by their community. For many, this is a notable period to live in Ireland as the Decade of Centenaries has just passed, where we remembered the pivotal years of the island’s history from 1912 to 1922.1 Marking 100 years since key events that shaped British and Irish history had come to pass, starting with the centenary of the Ulster Covenant and progressing to events of the First World War, we can reflect on the battles fought in foreign fields and events that sparked revolutions at home and abroad, what was gained and lost, and how a legacy sometimes becomes larger than the moments themselves. Imprinting a permanent footprint on a society’s cultural heritage, sometimes a simple word or phrase is just needed to remind someone of the event … Covenant, Somme, Easter Rising, partition. Each are powerful in their own right for making the average person in Ireland create a connection to these events. All are remembered by every community, for some as victorious moments of brave sacrifice for a greater good, for others as a betrayal of one community upon another, and for some as moments of needless loss with no real winners.

One of the most important centenaries of them all was marked in 2022: the implementation of the Anglo-Irish Treaty in 1922.2 The legacy of the treaty is still seen to this day. The island of Ireland remains partitioned, and the debate of Northern Ireland’s future is ongoing with no clear conclusion in sight. As of this moment of writing, it is an unusual puzzle to consider how the two distinct political divides of Ireland, Ulster Unionism and Irish Republicanism, will reflect this centenary. Both can claim victory. Ulster Unionists succeeded in maintaining Northern Ireland as part of the United Kingdom (UK), and Irish Republicans gained independence for their own state under the treaty. However, both can claim loss as well. Irish Republicans fought for all of Ireland to be an independent Irish republic; instead, Ireland was partitioned, and Southern Ireland became a Dominion in the British Empire that maintained the British Monarchy as the head of state.3 The treaty split Irish nationalism down the middle. Those that saw the treaty as the best possible compromise and a stepping stone to achieving a true Irish republic. Others saw it as a betrayal of their core principles. A bitter civil war in Ireland followed suit, which has remained a dark stain in Irish history and Irish Republicanism,4 and the state did not become a republic until 1948.5 Unionists were the biggest to lose of all, they were Irish Unionists by the start of the twentieth century that wished to maintain Ireland’s entire thirty-two counties place under the union, and broke their own Covenant in the process to gain what they have. Abandoning the three Ulster counties of Cavan, Donegal, and Monaghan due to their large majority Roman Catholic populations and betraying their Ulster Unionist counterparts to save their six counties.6

However, one must remember one key aspect about history – it is often like when we talk about the future; it is but a matter a collection of decisions and choices. The history of Ireland was just the same. The Irish border has played a fundamental role in determining British and Irish history, in more than just existence alone. Prior to Ireland’s partition, a number of suggestions were offered of where the boundary line could. In early 1914, the Chief Secretary for Ireland, Augustine Birrell, called upon three senior Irish civil servants with the task to propose a potential boundary for an Ulster exclusion zone for Unionists. The first was W. F. Bailey of the Estates Commissioners Office. He was the former secretary to the royal commission on public works in 1886, which meant he travelled extensively across Ireland including Ulster. For his proposal, he relied on physical geography than administrative boundaries. He suggested that the boundary cut straight through both of the county’s parliamentary divisions in county Fermanagh, running directly up the middle of the Erne waterways system, and utilise the system in west Ulster to create a solid boundary line. However, Conor Mulvagh points out that this would have been the most disruptive, as his proposed boundary line sliced through existing administrative units, thus making it impossible to accurately estimate how many people would have been in the excluded zone, or whether they were Roman Catholic or Protestant. This proposal was also made further questionable as he recommended the Westminster parliamentary division of North Monaghan should be designated in the exclusion zone, despite Protestants only making up a third of the constituency.7

The second proposal came from Sir Henry Robinson, Vice-President of the Irish Local Government Board, who came from an Anglican ascendent family and had an instrumental role in designing and implementing the Local Government Act of 1898. This was an instrumental feat, and Mulvagh points out Ireland’s 159 poor law unions were divided into 213 rural districts councils and a number of county borders were redrawn, making Robinson an impact expert for this task. For his proposal, he recommended local government boundaries as his operational unit, he allocated primarily the six-county option but differences on the frontiers. East Donegal’s Londonderry No. 2 and Strabane No. 2 were to be included in the exclusion zone, South Armagh and South Down were to be outside the exclusion zone for their large Nationalist populations, but included counties Fermanagh and Tyrone, and the city of Derry/Londonderry despite their demographics. He argued the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) was well armed and drilled, which would have caused a serious issue in regard to allocating nearly any part of these counties outside the exclusion zone. Furthermore, his proposal made considerations for local road and railways networks, to justify his scheme. He estimated the exclusion zone would have a population of 1,178,586, of which two thirds would be Protestants, and have a total land valuation of £4,545,708. In the end, despite his meticulous calculations, it was considered unworkable.8

The last proposal came from Sir James B. Dougherty, the Undersecretary for Birrell. He was a Presbyterian from Ulster, but a pro-Home Rule Liberal. For his chosen method of unit, he weighed the benefits and downsides of dividing the province by local government areas, parliamentary constituencies, and full counties which he eventually chose. This was due to prevent administrative complications concerning local government and Westminster seats, making the exclusion zone easier to establish and govern. He considered the use of county plebiscites but admitted that this would be complicated to implement, particularly as he conceded that Ulster Unionists would not abandon counties Tyrone or Fermanagh. Ultimately, it was this six-county option that was inevitably favoured, as it was the simplest proposal to map out and administer.9

In each of these alternate boundaries, Irish history would have been fundamentally altered. This year marks the centenary of the Irish Boundary Commission Report. The Commission recommended the transfer of 49,242 acres of land from counties Donegal and Monaghan to Northern Ireland. However, Northern Ireland would have lost more territory than it gained, with 183,290 acres from West Tyrone, South Armagh and Fermanagh going to the Irish Free State.10 Neither the Northern Irish nor the Free State governments were satisfied with the commissioners’ proposed report.11

If we were to speculate how history could have been altered if the boundary line had changed to the Commission’s recommendations in 1925, the ramifications would have been tremendous despite only being minor alterations on the frontier. In the long term, much of Northern Ireland’s political history would have seen small but significant changes. This would have been from the territories that were transferred to the Irish Free State with a population of 31,319, of which 3,476 (11.10%) was non-Roman Catholic, compared to the few territories Northern Ireland gained that contained 4,830 non-Roman Catholics out of a population of 7,594.12 The Protestant communities of these newly incorporated territories would still have likely declined over time, as they did in our timeline regardless of the change in the border. But the territories that were to be ceded to the South had maintained significant Roman Catholic and Nationalist communities that still continue to this day. This would have greatly helped local Ulster Unionists, particularly in county Fermanagh. An example where this would have been seen is in general election results, as from 1950 to the present day the UK constituency of Fermanagh and South Tyrone has been a hotly contested seat between Unionists and Nationalists. From 1950 to 2024, Nationalist candidates have won the seat fourteen times out of twenty-five general and by-elections, with a majority of just 4,987 in 1979 to as little as 4 in 2010.13 If the boundary had changed in 1925, in the modern era, Unionists would have likely won the constituency in all these elections seat due to the reduced number of registered Nationalist voters. This would have prevented the historic election victories for ‘Anti H-Block’ candidates Bobby Sands and Owen Carron in 1981, that won the seat with majorities 1,447 and 2,230 votes, respectively.14

However, the biggest change that this alternate boundary would have made would have been seen in recent times. If Northern Ireland had changed the boundary in 1925, it is likely that two historic moments would never have happened. The first was the 2019 UK general election, which was a notable election as it was the first time Westminster election in which the number of Unionists elected did not exceed the number of Nationalists. For the 2019 general election, Sinn Féin would have likely still won the UK constituency of Newry and Armagh despite the loss of South Armagh, as it had a majority of 9,287. However, Sinn Féin won the constituency Fermanagh and South Tyrone by a mere fifty-seven vote majority despite Social Democratic and Labour Party also competing, and the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) was the only party that stood in the constituency.15 If the border had changed in 1925, it is likely the UUP would have won the seat. The second moment would have been a few years later in 2022, when an election was held for the Northern Ireland Assembly and Sinn Féin became the largest party with twenty-seven seats, followed by the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) being the second largest with twenty-five seats. This was an historic moment, as this was the first time that a Nationalist and Republican party had won the most seats for the Northern Irish Assembly.16 All constituencies for the Northern Ireland Assembly have five seats since 2017, and during the 2022 assembly elections Sinn Féin won three out of five seats in four constituencies. These were Mid Ulster, Newry and Armagh, West Tyrone, Fermanagh and South Tyrone; the last three constituencies are areas that would have changed due to the border. If the border had changed in 1925, given the resulting decrease in both Roman Catholic and Nationalist voters from boundary changes, including a slight increase in potential Protestant Unionist voters in Armagh and West Tyrone, it is possible Unionist candidates could have won an extra seat in these three constituencies. Reducing Sinn Féin’s seat total to 24, leaving the DUP as the largest party in the Northern Ireland Assembly, would thus prevent Sinn Féin’s historic electoral victory from ever occurring. It must be noted that while the Sinn Féin may have lost these seats, the DUP would not have automatically gained them. A DUP candidate was eliminated on the final round of voting for the constituency of Fermanagh and South Tyrone, yet it was Traditional Unionist Voice candidates that were eliminated on the final round of voting for the constituencies of West Tyrone and Newry and Armagh.17 It could be argued that this alternate boundary would have only prevented two inevitable political outcomes that would still have occurred at least 10 or 20 years later. In 2021, the census for Northern Ireland showed that Roman Catholics out-numbered Protestant denominated Christians for the first time.18 Even if the Irish border had been altered in 1925, this would have still occurred, but with a slimmer majority. The only difference would have been that if Sinn Féin had won a decade later, it would not have occurred near the centenary of the establishment of Northern Ireland.19 An important moment for Ulster Unionists, which was overshadowed by the prospects of a future united Ireland appearing more realistic than ever before.

History often leads to speculation of unanswered ‘what ifs’, but does counterfactual history have academic merit? In 1974, Dr Paddy Griffith from the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst organised a wargame to determine what could have happened if Nazi Germany in September 1940 launched its planned invasion of Great Britain, Operation Sea Lion. After two days with up to thirty participants divided in two teams and given military reports of that time, the wargame came to a unanimous conclusion that a German invasion force would have been defeated.20 As Northern Ireland commemorated its centenary in 2021, this was a period of reflection of partition. When discussions of partition were being made, some Unionists suggested the exclusion zone should be all nine counties of Ulster, despite the large Roman Catholic populations in Cavan, Donegal, and Monaghan.21 This work will look back at this decision and ask the academic question, ‘what if’? What if a nine-county Northern Ireland had been created in 1921, how could history have changed? Could Ulster Unionists have remained in control in such a scenario?

Historiography

Questions on the impact of the Irish border have been raised on numerous occasions. During the Troubles, repartition had been considered a few times by the British government during the Troubles and it was first suggested in a pamphlet by Julian Critchley, Conservative MP for Aldershot.22 Liam Kennedy, having listened to discussions concerning the boundary line, made a case to help resolve the crisis in Northern Ireland by presenting four models of how the new border could appear, primarily ceding Nationalist majority areas in counties Fermanagh, Tyrone and South Armagh, and the city of Derry/Londonderry. In his writing, he also gave speculations as to how these plans could be implemented, including a population exchange to help make the revised Northern Irish state more ethnically homogenous to prevent any further conflict in Ireland.23 These suggested border studies by Kennedy were planned for a potential future scenario, not a counterfactual history like this work. Nevertheless, there is a growing counterfactual history movement within Irish academia as a method of analysis. For example, in 1999, Alvin Jackson explored what might have been if Home Rule had been enacted in 1912, analysing the state of Ulster Unionist by 1912 and clauses within the Third Home Rule Bill that led to issues of it being accepted. What is interesting about the work is that he includes speculations during this period by local actors and writers involved in the Irish Home Rule debate during the early twentieth century, of how Ireland would have been shaped if a Home Rule Parliament was established. These include Peter-Kerr-Smiley, Pembroke Wicks, and Terence MacSwiney, both Unionist and Nationalist outlooks, to reflect how both sides of the political debate foresaw the then future of Ireland in the Home Rule.24 This growing counterfactual history movement within Irish academia was then utilised by RTÉ to help engage the Irish public with local history through a new means. From 2003 to 2009, Diarmaid Ferriter hosted a weekly ‘What If’ radio programme on RTÉ 1. Although the show was for entertainment purposes, the programme invited a number of academics and historians to provide their expert speculations on what could have occurred if certain events had or had not occurred. These often varied – what if there had not been no 1916 Rising? What if Britain had imposed restrictions on Irish immigration in the 1950s? What if the Treaty Ports had not been returned in 1938? In 2006, Ferriter published a book looking at twenty events that were discussed on the show. Although these are well analysed predictions and speculations, often prepared before the show was aired on the radio, they do not provide a detail of source analysis or referenced as an academic work would have done. However, the weekly show highlighted a new way for Irish historians to review certain history issues and allowed the general Irish public access to listening to these great debates.25 During the same year, Liam Kennedy and David S. Johnson looked at Ireland’s historic relations to Great Britain. As they examined the economic impact of Ireland’s political union with Great Britain since 1801, they considered ‘alternative historical pathways’ to compare how Ireland’s economy could have performed in the ninetieth century outside the UK. They considered a number of constitutional variations for Ireland during this period from a variation of the Constitution of 1782 for the Parliament of Ireland, a federal UK arrangement, and an independent Irish state.26

Following these works, more academic counterfactual history questions were raised, particularly near and during the Decade of Centenaries in Ireland. For instance, Daniel Mulhall wrote an article work similar to Alvin Jackson’s, of what if Charles Stewart Parnell had delivered Irish Home Rule in 1904. He looked at what factors had hindered his efforts and gave an analysed speculation of what the impact could have been for Ireland if this had occurred. He speculated if Ireland had achieved Home Rule by 1904, then it would have likely obtained political independence from the UK through constitutional means following the First World War.27 Alvin Jackson was invited to take part in a panel for an Oxford Irish History Seminar on 18 May 2022, along with Caoimhe Nic Dháibhéid and Charles Townshend, concerning ‘Ireland without Partition: Counterfactual Histories’.28 Unfortunately, the event was later cancelled. Some academics have given brief speculations of if a nine-county Northern Ireland was created, but there is a difference of opinion how this may have affected its history. Mike Commins claims if such a state was created then Ulster Unionists would not have had nearly a century of control of Stormont, due to census records showing in recent decades Roman Catholics have become the largest denomination in the province.29 Jeremy Smith, nonetheless, argues that this fear by Ulster Unionists of a demographic ‘take over’ could have been prevented. Under a nine-county state, as the Roman Catholic population would have been significant enough to offer effective resistance against any potential bullying from a Unionist Stormont government. This would have forced to Ulster Unionists to consider taking a different approach, to accommodate and include Roman Catholic to the new Northern state. By eradicating policies or schemes that were discriminatory, providing access to political, economic and social benefits, introducing various cultural and institutional to unify ethnic and cultural difference – it could have altered or reduced the political ambitions of Roman Catholics in Ulster, and eventually recede a threat of a potential Nationalist take over.30 Pauline Collombier took an interesting approach; her work considered visions of the future by Irish Unionists and Nationalists of Ireland under Home Rule, during the Home Rule crises from 1870 to 1914.31 This provides an interesting narrative of the different aspects of Irish Home Rule, and what different political factions thought would be the immediate and long-term ramifications if the Government of Ireland Bills had passed.

Details

- Pages

- 260

- Publication Year

- 2025

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781803749907

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781803749914

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781803749891

- DOI

- 10.3726/b22808

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2025 (July)

- Keywords

- Samuel Beckton The Unbroken Covenant Counterfactual Alternative History Ireland Ulster Unionism Nationalism Border Partition

- Published

- Oxford, Berlin, Bruxelles, Chennai, Lausanne, New York, 2025. 260 pp., 20 fig. b/w, 7 tables.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG