Racialism and the Media

Black Jesus, Black Twitter, and the First Black American President

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- Figures

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Racialism and the Media

- Chapter One Contemporary Zip Coons: The Problem with Funny

- Chapter Two Ghettofabulous: How Low Can You Go?

- Chapter Three Advertising and Black Folks: Whassup!

- Chapter Four Black-ish and the Changing Nature of Black Identity

- Chapter Five Balancing Stereotypes: Black Male and Female Roles on Prime-Time Television

- Chapter Six A Satirical Parody: Black Jesus in the Hood

- Chapter Seven Deconstructing Intersectionality in Crash

- Chapter Eight Black Twitter, Interpretive Communities, and Cultural Capital

- Chapter Nine President Barack Obama: Biased Frames and Microaggressions

- Chapter Ten Science Fiction and Fantasy: Going Where Few Blacks Have Gone Before

- About the Author

- Index

- Series index

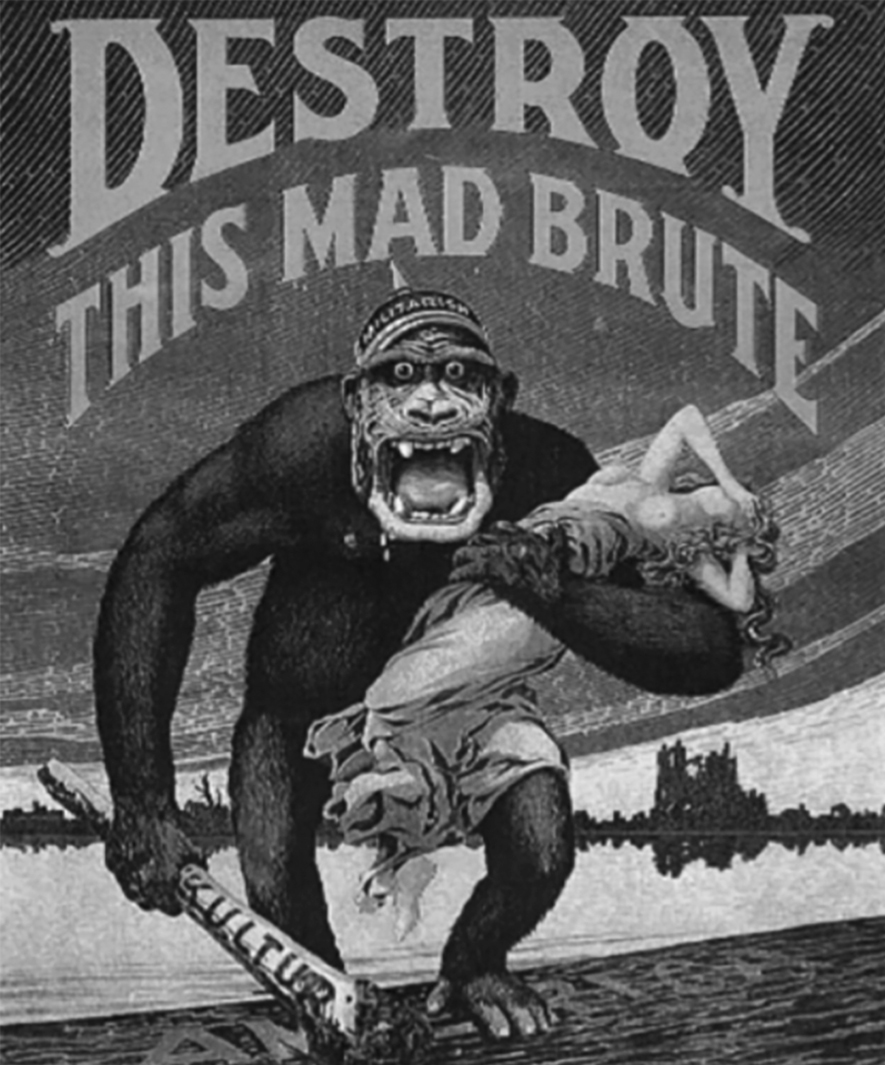

Figure I.1: King Kong “Destroy this mad brute” WWII recruitment poster

Figure 3.1: Kool-Aid “Old School Flavor” basketball stereotype

Figure 3.2: Dunkin Donuts “Charcoal Donut” ad in Thailand

Figure 3.3: Cheerios “Interracial family” Super Bowl commercial

Figure 3.4: Gerber “Earn your masters in chewing” placement status

Figure 3.5: Pine Sol “Intensity” reframing the mammy stereotype

This book is the result of twenty-five years of experiencing, teaching, and researching black images and messages in the media as a black woman in America. I want to thank my students who have been essential to my research and teaching inside and outside of the classroom. I want to thank my family and friends who understand my obsession with the media and love me anyway. They have tolerated and motivated me throughout my career. I want to thank the black actors, writers, directors, producers, and others who have brought to life the stories and characters I love and hate. I want to thank the University of Iowa, the School of Journalism and Mass Communication, and the African American Studies program for continued encouragement and support. Finally, I want to thank my God and savior Jesus Christ who keeps me lifted up.

←x | 1→Introduction: Racialism and the Media

Look at the poster of King Kong. Now imagine replacing King Kong with Los Angeles Lakers’s basketball champion Lebron James. Draped across James’ left arm is model, Gisele Bundchen in a similar teal dress. His mouth hangs wide open as if he is growling just like King Kong, and in his right hand rather than holding a club he bounces a basketball.

This was the April 2008 cover of Vogue Magazine. It perpetuated a number of issues concerning normalized stereotypes, biased racial framing, and problematic historical myths concerning African American culture. For example: the comparison of black men to apes, the notion that black men are obsessed with white women, and the historical myth that black people coming out of Africa are like apes and have an animalistic or violent nature. This cover fueled a significant amount of controversy concerning racists and racism (Hill, 2008; Lebron, 2008; Morris, 2008; Stewart, 2008). The design of the cover is too close to the King Kong poster to argue that it was not the inspiration. So, why would photographer Annie Leibovitz create it? Is she a racist? Why would Lebron James agree to pose like King Kong? Is he okay with racism? Why would Vogue Magazine use this image on their cover? Are they comfortable perpetuating racism?

In another example, the recent blockbuster movie Black Panther (2018) featured the Jabari Tribe of Wakanda where the leader M’Baku is called Man-Ape. The tribe is known as the White Gorilla Cult and they use the loud, repeated ←1 | 2→grunt of the gorilla during conflict. The Jabari Tribe also lives in the mountains where it is colder, so they wear fur to cover up. In the movie this tribe displayed an aggressive image that could be connected to the historical myth of black men as apes or black people as animalistic. This was apparently part of the original comic book, written by a white man, but why would a black director and writer Ryan Coogler and Joe Robert Cole keep this stereotypical idea of an ape cult in the movie version? Are they racists? Why would actor Winston Duke play a character where the black man is called a man-ape? Is he okay promoting racism?

The purpose of this book is to explore the notion of racialism. Some people suggest that the first Black American president brought with him a post-racial society. It is obvious that that is not the reality. However, the nature of racial ideology has changed in our society. Yes, there are still ugly racists who push uglier racism, but there are also popular constructions of race routinely woven into mediated images and messages.

Racialism is the normalization of racial images and messages that impact cultural representation. Sometimes it is racist and sometimes it is not. Many media ←2 | 3→constructions are based on racial images and messages that have become common and accepted in our society today. It is not a good thing, but it also may not be a racist thing.

The Vogue cover is similar to the King Kong poster, yet is it possible that photographer Annie Leibovitz is not a racist? With what I know about Lebron James, especially beyond his basketball talent, I don’t believe he is okay with racism. And I think Vogue Magazine would probably prefer not to perpetuate racism on their cover. I doubt that Ryan Coogler and Joe Robert Cole would be okay with propagating the Jabari tribe as apes if they saw it as a racist image. And I’m sure Winston Duke didn’t want to promote racism in the dynamic role he played. So, the question is, how do we explain these racial images and messages outside of the extreme notion of racism? My answer is racialism.

In the twenty-first century, we need a more nuanced understanding of racial constructions. Denouncing anything and everything problematic as racist or racism simply does not work, especially if we want to move toward a real solution to America’s race problem. Under the umbrella of racialism, racism is alive and well. Particularly, it encompasses the more historical actions and ideas tied to hate and violence. For example, a white person calling a black person the n-word, hanging a noose in the D. C. National Museum of African American History and Culture, wearing blackface or a KKK robe, and an Alt-Right rally that ends with one person dead and nineteen people injured. These are obvious racist acts. Racism is included under the umbrella of racialism, but my goal is to focus on something else. My focus is on the racial images and messages constructed by the media that do not or should not fall into the loaded category of racism.

Racialism

We live in a society filled with racial situations, messages, practices, and images. In this book, racial constructions are examined using a more nuanced approach. Racialism is a concept that includes, but moves beyond traditional racism. It involves images, ideas, and issues that are produced, distributed, and consumed repetitively and intertextually based on stereotypes, biased framing, and historical myths about African American culture. These representations are normalized through the media, ultimately shaping and influencing societal ideology and behavior.

Specifically, there are four significant areas under the umbrella of racialism. First, the common use of stereotypical images and messages as repetitive ideas about black culture. Second, biased racial framing which involves the shaping ←3 | 4→and creation of black cultural issues in adverse ways. Third, historical myths such as the derogatory use of knowledge and understanding linked to Africa and African traditions. Fourth, traditional racism involving purposeful hatred and malicious acts.

Sawrikar and Katz (2010) argue against the notion of white supremacy being used synonymously with racism because it situates white as the fixed reference point and places it at a higher social power than all other groups. They discuss the need for cultural competency to become the recognition and acceptance of difference with two components that are key: awareness and sensitivity. This means it is important for a person to make sure they have sufficient knowledge (awareness) about a group and that they challenge (with sensitivity) any stereotypes, biased frames, and historical myths encountered.

Delgado and Stefancic (2012) believe that there is a difference between the ideal notion of racism and the real notion of it. They explain that the ideal focuses on thinking, attitude, and discourse because race is a social construction, not a biological one. They also discuss how racism is used as a means for society to create racial hierarchies allocating privilege and status.

we may unmake it and deprive it of much of its sting by changing the system of images, words, attitudes, unconscious feelings, scripts and social teachings by which we convey to one another that certain people are less intelligent, reliable, hardworking, virtuous and American than others. (p. 17)

Bonilla-Silva (2014), in his book Racism without Racists, suggests that racial discrimination still affects the lives of people of color because new racial constructs are safeguarding the traditional racial order as good as the old ones. He suggests that for most white people, racism is simply an idea or attitude.

Most contemporary researchers believe that since the 1970’s, whites have developed new ways of justifying the racial status quo distinct from the “in your face” prejudice” of the past. Analysts have labeled whites post civil rights racial attitudes as “modern racism,” “subtle racism,” “averse racism,” “social dominance,” “competitive racism,” or the term I prefer, “colorblind racism”. (p. 259)

Carr (1997) believes that the term “racist” itself too often gets confusing.

The problem is that discrimination is no longer distinguished from its presumed cause, prejudice. Racism became both the cause and effect … It [the term] does not distinguish between the racism of the oppressor and the oppressed … There is no way to make this distinction, there is only the term racist, as an ideological phenomenon. (p. 155)

←4 | 5→Enlightened racism, as discussed by Jhally and Lewis (1992), moves in this same direction arguing that racial bias is not only about simple skin pigmentation but also cultural class position. Their study of The Cosby Show explored how and why white viewers identified with an upper-middle class black family.

What shows like The Cosby Show allow, we discovered, was a new and insidious form of racism. The Huxtables proves that black people can succeed; yet in doing so they also prove the inferiority of black people in general (who have, in comparison to whites, failed). (p. 98)

Details

- Pages

- X, 160

- Publication Year

- 2020

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781433172908

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433172915

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781433172922

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433172885

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433172892

- DOI

- 10.3726/b16689

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2020 (June)

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Oxford, Wien, 2020. X, 170 pp., 6. b/w ill.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG