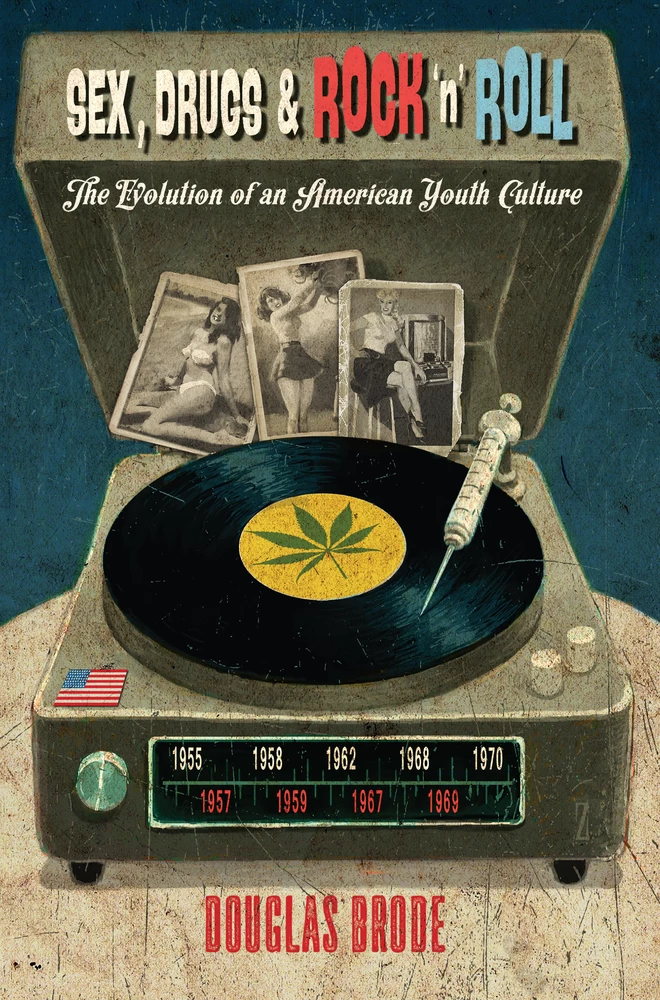

Sex, Drugs & Rock ‘n’ Roll

The Evolution of an American Youth Culture

Summary

As the entertainment industries came to realize that a youth market existed, providers of music and movies began to create products specifically for them. While Big Beat music and exploitation films may have initially been targeted for a marginalized audience, during the following decade and a half, such offerings gradually become mainstream, even as the first generation of American teenagers came of age. As a result the so-called youth culture overtook and consumed the primary American culture, as records and films once considered revolutionary transformed into a nostalgia movement, and much of what had been thought of as radical came to be perceived as conservative in a drastically altered social context.

In this book Douglas Brode offers the first full analysis of how an American youth culture evolved.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Prologue Twixt Twelve and Twenty: The First American Teenagers

- Chapter 1. Toward a New American Cinema: Three Films That Altered Everything

- Chapter 2. Shake, Rattle and Rock: The Big Beat on the Big Screen

- Chapter 3. Bad Boys, Dangerous Dolls: The Juvenile Delinquent on Film

- Chapter 4. I Lost It at the Drive In Movie: An All-American Outdoor Grindhouse

- Chapter 5. The Tramp Is a Lady: Mamie Van Doren and the Meaning of Life

- Chapter 6. Surf/Sex/Sand/Spies: The Battles of Bikini Beach

- Chapter 7. The Last American Virgin: Sandra Dee and the Sexual Revolution

- Chapter 8. Formulating a Feminine Mystique: The Emergent American Woman on Film

- Chapter 9. “The British are Coming!”: When Bob Dylan Met the Beatles

- Chapter 10. Go Ask Alice: The Drug Culture on Film

- Chapter 11. Revolution for the Sell of It: The Beat Generation and the Hippie Movement

- Chapter 12. Lonesome Highways: Of Car Culture and Motorcycle Mania

- Epilogue Let the Good Times Roll: Once Upon a Time in the Late 1950s/Early 1960s

- Notes

- Bibliography (Selected)

- About the Author

- General Index

- Film Title Index

- Series index

← xiv | xv → Prologue

“Yeah, yeah, yeah, I go to swingin’ school.

The cats are hip and the chicks are cool.”

—Bobby Rydell, Because They’re Young, 1960

During the second week of September 1955, between ten and fifteen million young Americans, the vast majority twelve years old, embarked on the first-stage of their post-childhood lives. The previous spring, they had graduated from grade schools in large cities and small towns across the industrial northeast, the strictly-segregated south, a largely rural southwest, wide-open prairies across the Midwest, and the isolated, in many ways insular northern tier. They entered larger middle- and junior-high schools that collected such teenagers, as they would soon be known. Unbeknownst to them, these youngsters formed a virtual tidal wave: baby-boomers, born during the middle of World War II. Many were the offspring of men and women who married shortly after meeting so as to respectably engage in sex before servicemen were shipped overseas.1 Never before in the country’s social history had such a vast number simultaneously showed up for the second phase of their educations. School systems across the country were unprepared and overwhelmed.2 Less obvious ← xv | xvi → was that a Sea Change in morals, mores, and manners would shortly occur. Or that the movies they chose to watch and music they listened to would henceforth reflect and derive from these new kids on the block.

Most shared a common core: what we now refer to as popular culture. At the time, there was no real consciousness of this being anything other than appealing, insignificant experiences. One key innovation was that a large number had grown up watching television.3 Until a year previous, the TV set in a living-room was a status symbol.4 An antenna on the initial home in a neighborhood to boast one indicated an affluent household. Here was, until those ugly things proliferated, the great signifier of belonging to a new abundance and affluence which, like the advent of mainstream TV, essentially began in 1948. Following a postwar recession, the American economy had boomed.5 With each passing year, the price of a TV set plummeted. Likewise, the quality with which TVs were turned out (assembly-line style, like cars in Detroit) diminished. Early on, The Tube was encased in oak consoles, with faux antique doors that could be opened when a family chose to turn on the set. By 1955, the year that television went viral, new models were tinny, cheap-looking. More significantly, they would be turned on at the beginning of each day, off again at bed-time. That hour stretched ever later, thanks to late-night talk shows and old movies.6 If two years earlier, kids begged to be admitted into a TV-owning household to watch Howdy Doody or its less-remembered competition—Rootie Kazootie, Kukla, Fran, and Ollie, The Magic Cottage—with the child residing there, now TVs were accessible for all but the poorest. Owing to the limited number of channels, more often than not everybody watched the same shows. A great number of these became central to people’s lives.7 There was of course I Love Lucy on Monday and, later, on Wednesdays, Walt Disney’s first hour-long show. The Davy Crockett Craze dominated these kids’ waking hours during the latter part of 1954 and throughout the winter of 1955. Only three episodes were produced during that first season, broadcast between Dec. 15, 1954 and February 23, 1955. Yet kids were entranced; mesmerized even.8

For earlier generations, radio created a sense of community within families who listened devotedly to their favorite shows. TV, however, exerted a hypnotic effect without precedent. A nightly entertainment buffet included old films, a video mosaic of Hollywood history. Also, serious live drama, inexpensive children’s programming, situation comedy, quiz shows, ancient cartoons, and something innovative called ‘the news.’ Theatrical newsreels like The March of Time soon disappeared, rendered irrelevant.9 Why watch a week-old summary when, for a similarly-paced fifteen minutes, up-to-date news appeared on TV nightly? Key details were picked up from the Talking Heads by children, ← xvi | xvii → playing on the floor while waiting for Crusader Rabbit to begin. Swarthy, angry Sen. Joseph McCarthy frightened some of them even more than the villains on Superman. Kids knew a Red Scare existed but left that for grown-ups to deal with. The war in Korea, which for reasons that they could not comprehend was referred to as a “conflict,” played nightly until its indecisive end in 1953.10

*

That sense of indecisiveness came to define life in those times. The Fifties would not be thought of as the ‘Happy Days’ until the early 1970s. Then, a mythic vision of the past was created via that TV show, movies like American Graffiti (George Lucas, 1973), and onstage the Broadway play Grease. Happiness, when that decade is less romantically considered, had not been the reality for most Americans in an era when the Cold War cast a mushroom shaped shadow over the quietude of daily lives. In one film, The Atomic City (Jerry Hopper, 1952), Gene Barry received top billing as a physicist working in Los Alamos. The focus remained on this man’s ten-year-old son (Lee Aaker). The child upsets his father by asking questions about what will happen when the atomic war comes. His dad tries to get the lad to change the phrasing to “if.” While the boy promises to do so, he keeps forgetting. Most kids who caught this B item at a Saturday matinee couldn’t boast a parent who worked in the atomic industry. Like the film’s child hero, many had gradually become convinced, owing to nuke drills, that end of days was nigh. Many were exposed to the educational short Duck and Cover (Anthony Rizzo, 1951) in which a Disney-like turtle assured kids survival was possible, offering hints how to do so. The advice was so patently absurd (like holding a piece of paper over one’s head) children laughed out loud. A few lived in house-holds featuring well-stocked bomb shelters in the basement.11 None of those precautions, however well-intended, convinced the first generation of atomic-age children they were likely to reach the age of 21. They’d seen such science-fiction flicks as The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (Eugene Lourie, 1953), Them! (Gordon Douglas, 1954), and Godzilla, King of the Monsters! (Terry Morse, Ishiro Honda, 1955) in which radiation releases prehistoric creatures, such diversions speaking to our worst collective fears.12 Happy days? For David Halberstam, “it was a mean time.”13 Not on the surface. During the Eisenhower era, life ebbed and flowed as if all was right with the world.

Still, underneath that uneasy calm . . .

A few sage observers had early on seen this coming. Some expressed it in what was then largely considered escapism: The Movies. In 1943, Alfred ← xvii | xviii → Hitchcock (1899–1980) collaborated on Shadow of a Doubt with Thornton Wilder (1897–1975). The latter’s beloved play Our Town (1938) had idealized life in middle-America during the pre-World War II years. Like most stage productions, the 1940 film directed by Sam Wood was shot on a studio back lot; the sort of quasi-realistic, semi-stylized approach employed for the Andy Hardy series starring Mickey Rooney as a 1930s predecessor to the ‘50s teenager. With Shadow of a Doubt, Hitch broke with tradition. He shot in an actual California town, Santa Rosa, for realistic verisimilitude.14 Despite Wilder’s participation, this project played as a rejection of everything Our Town said about such a “Grovers Corners” place. The heroine, Charlie Newton (Teresa Wright), a sixteen-year-old, offers an early incarnation of the typical teenager soon to emerge. A thriller plot has this wide-eyed waif dealing with her once beloved Uncle Charlie (Joseph Cotton), openly posing as a phony aristocrat though secretly an American Jack the Ripper. In one of the film’s remarkable set-pieces, Charlie Oakley confronts Young Charlie:

What do you know, really? You’re just an ordinary little girl, living in an ordinary little town. You wake up every morning of your life and you know perfectly well that there’s nothing in the world to trouble you. You go through your ordinary little day. And at night, you sleep your untroubled ordinary little sleep, filled with peaceful stupid dreams . . . You live in a dream. You’re a sleepwalker, blind. How do you know what the world is like? Do you know the world is a foul sty? . . . The world’s a hell. What does it matter what happens in it? Wake up, Charlie. Use your wits. Learn something!15

What Uncle Charlie wants Young Charlie to learn is his philosophy. In a nutshell, nihilism: everything adds up to nothing; life is without rhyme, reason, meaning. Uncle Charlie is the shape of things to come. He is The Fifties—“mean,” dark, threatening; a virtual cesspool of horrors churning below a genteel exterior—before that decade even began. In an era when virtually everyone was absorbed with the war, most Americans had no time for soul-searching. There was right and there was wrong. Hitler was wrong. In fighting what Gen. Eisenhower called our Crusade in Europe,16 we instantaneously became white knights. Shadow of a Doubt is the only Forties movie in which WWII doesn’t seem to exist.

But there is a more terrible truth here. Young Charlie, the small-town girl par excellence, knows on some instinctual level that things were not precisely right before Uncle Charlie stepped off that train. “We just sort of go along and nothing happens,” she muses early on. “We’re in a terrible rut. What’s going to be our future?” As in Shakespeare’s vision of Hamlet’s Elsinore, peasants bound about as if nothing is wrong while a few troubled souls secretly admit deep fears: Something’s rotten in the state of Denmark. And in the then-contemporary U.S. ← xviii | xix → when World War II ended, rather than a wonderful new world order, the grim Cold War began. For a seminal film of that time, The Best Years of Our Lives (William Wyler, 1946), screenwriters Robert Sherwood and MacKinlay Kantor intended their title as ironic. While the boys were overseas, everything altered, if subtly. On return, the effect was akin to a Twilight Zone (1959–1964) ← xix | xx → episode in which some astronaut descends to find the surface of life the same, its essence changed in a slightly surreal manner. He can’t place what’s wrong. Something, though, clearly is. To blend Wilder with Thomas Wolfe, veterans discovered you can’t go home again to Our Town. Hollywood expressed this sensibility via the noir style, anticipated by Hitchcock. Confused, angry anti-heroes (an earlier notion of simple, pure good-guys no longer existed) dutifully walked the mean streets of what once seemed great metropolises. Such places had degenerated into asphalt jungles during our idealistic if, as things turned out, naïve overseas quest to save the world.

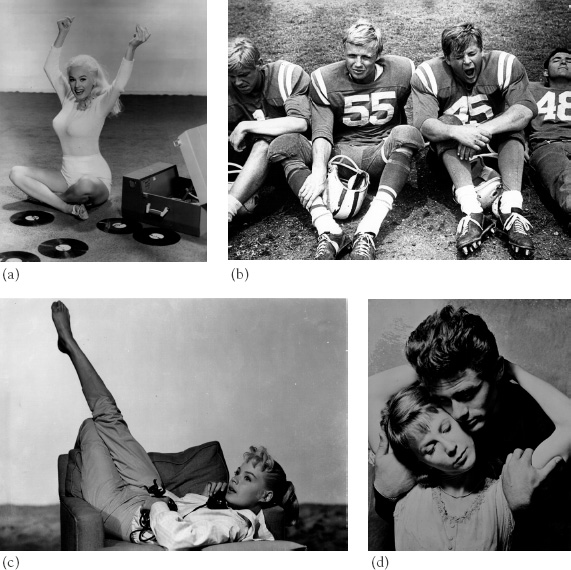

YOUTHFUL IMAGES OF A NEW ERA: (a) Mamie Van Doren delights in her record collection (courtesy: Universal); (b) all-American boys (Jon Voight, center) relax after football practice in Out of It (courtesy: Pressman-Williams/United Artists); (c) a typical suburban teen (Sandra Dee) has her wish for her own phone granted (courtesy: Universal); (d) despite Pre-World War I period trappings (the film mostly takes place in 1915), James Dean and Julie Harris embody the angst of young love in a manner that spoke directly to Fifties teens in East of Eden (courtesy: Warner Bros.)

Noir titles indicated a gnawing sense of disillusion with the way things were: Somewhere in the Night (Joseph L. Mankiewicz, 1945), The Big Sleep (Howard Hawks, 1946) Out of the Past (Jacques Tourneur, 1947), Nightmare Alley (Edmund Goulding, 1947), White Heat (Raoul Walsh, 1948). Though 1955’s teenagers had been too young to experience such dreary visions during their theatrical releases, TV venues such as the legendary Million Dollar Movie now showcased such films.17 Impressionable youth absorbed such images of a world gone sour and, in time, insane, absurd. Hitchcock captured the tenor of those times with Rear Window (1954), expanded from a short work of pulp-fiction by Cornell Woolrich.18 The film offered a color-noir with a vivid tableau of diverse residents in a lower-Manhattan housing complex. These people never acknowledge, much less speak to, one another. In addition to the expected thriller plot, Hitch’s film offered an oblique commentary on an emergent way of living (or existing) in which the neighborly attitudes of Main Street, U.S.A. were all at once gone.

A term would be coined to describe this sorry state of affairs: The Lonely Crowd, introduced in a 1950 book by sociologist David Riesman and several colleagues.19 They noted, with due concern, that centuries of an American sense of ongoing community, which had reached its peak during World War II, suddenly gave way to an alternative in which people sealed themselves off and apart in invisible cocoons. Not even the old standby of sending boys off to combat helped. A decade after what author James Jones defined as “The Last Good War”20 ended, the first bad one, Korea, set the pace for Vietnam and Iraq. Regrettably, Hitchcock had been point-on. Uncle Charlie didn’t bring a waking nightmare to Santa Rosa, aka Grovers Corners. It had been there all along, waiting for a catalyst to rip open this dark underbelly of life on Main Street, U.S.A.

*

← xx | xxi → Notably, there are no blacks on view in Santa Rosa. Nor were there any in Our Town. A few household servants, perhaps, living on the far edges of society; some porters for the railroad. Though no warning sign is on view to let visitors know, Grovers Corners existed for Anglos only. Such prejudice was not reserved for African Americans. Italians, Greeks, Jews, the Irish . . . a Polish lower-working class are mentioned briefly in Wilder’s play, though never included in the drama. However rich the vocabulary of residents, the term ‘integration’ remains unknown. But during World War II, President Harry Truman followed up on the late President Roosevelt’s desire to alter that. By 1944, the military had belatedly become racially diverse.21 When the overseas war concluded, a battle for Civil Rights at home began. If their parents felt vaguely threatened by such figures as Dr. Martin Luther King, a large number of teenagers were intrigued. Some wanted to get involved. A few actually did, joining in marches, protests, discussions.22

This was a time of change, drastic change. No one felt the waves of transition more than baby boomers, caught in the middle between past and future.23 Though big cities and small towns still existed, something new had, in addition to TV, swept the land. Ever more kids were raised in suburbia. William J. Levitt (1907–1994) in 1946 had created a housing development near Hempstead, Long Island, bearing his name: Levittown.24 Rich and poor weren’t welcome; suburbia was a middle-class undertaking. Houses went for $5,000 each, the top price a bread-winner earning $3,000 a year could handle. Though Levitt was Jewish, God’s chosen people were not particularly welcome. Blacks? Verboten! Not that Levitt was a racist. Rather, he fancied himself a hard-nosed businessman, grasping that the vast majority of working class whites whom his suburban dream spoke to weren’t ready for ethnic neighbors, even in the industrialized northeast.25

At any rate, “It was Bill Levitt who first brought (Henry) Ford’s techniques of mass production (and assembly line construction) to housing.”26 Similar buildings were according to Paul Goldberger

Details

- Pages

- XXXII, 304

- Publication Year

- 2015

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433128868

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781453915066

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781454192145

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781454192152

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433128875

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-1-4539-1506-6

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2014 (November)

- Keywords

- Beatles Bob Dylan Motocycles American Dream Binini Beach

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, Oxford, Wien, 2015. XXXII, 304 pp., num. ill.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG