Alternative Worlds

Blue-Sky Thinking since 1900

Summary

Following a roughly chronological order from the turn of the nineteenth century to the present, this book explores the dreams, plans and hopes as well as the nightmares and fears that are an integral part of alternative thinking in the Western hemisphere. The alternative worlds at the centre of the individual essays can each be seen as crucial to the history of the past one hundred years. While these alternative worlds reflect their particular cultural context, they also inform historical developments in a wider sense and continue to resonate in the present.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author(s)/editor(s)

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Introduction

- In Praise of Blue-Sky Thinking

- Bibliography

- Websites

- Part I Shaping the Earth and the Sea

- 1 Atlantropa: One of the Missed Opportunities of the Future

- The Plan

- Water Power and World Peace

- Fact, Fiction and the Power of Faith

- Atlantropa on Film

- Atlantropa in Fiction

- Afterlives

- Bibliography

- 2 Alternative Mediterraneans Six Million Years Ago: A Model for the Future?

- The Significance of Salt: The Messinian Salinity Crisis

- Drowned River Valleys: Main Evidence for a Desiccated Mediterranean

- Why the Strait Closed: The Formation of a Land Bridge between Morocco and Spain

- Closing the Strait of Gibraltar: Climate Control or Macro-Engineering Hubris?

- Bibliography

- 3 Atlas Swam: Freedom, Capital and Floating Sovereignties in the Seasteading Vision

- Introduction: Launching the Seastead Idea

- Seasteading and the Search for a Floating Utopia

- The Anarcho-libertarianism of Seasteading: Where Economic Man Meets Burning Man

- Seasteading as New, New Urbanism

- Sovereignty, Territory and ‘Aquatory’

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Part II The 1960s: Building the Future

- 4 The Last ‘City of the Future’: Brasília and its Representation in Literature and Film

- Bibliography

- 5 The Post-War High-Rise: Promise of an Alternative World

- Impact of Technology

- The Multi-Level City

- The High-Rise in the City

- Looking Forward

- Bibliography

- 6 ‘The landscape is coded’: Visual Culture and the Alternative Worlds of J.G. Ballard’s Early Fiction

- Bibliography

- Part III Alternative Lives

- 7 Designed Surfaces and the Utopics of Rejuvenation

- Storying Surface: Patina and the Formation of Narrative

- Consuming Surfaces

- Cosmetic Intervention and Happy-Ageing

- The Mask of Age

- Conclusion: Re-storying the Ageing Process

- Bibliography

- 8 The Alternative World of Michel Houellebecq

- Introduction

- The Plot

- A Fast-Paced Society

- Acceleration

- Standstill

- Le Néant

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- 9 From the American Myth to the American Dream: Alternative Worlds in Recent Hollywood Westerns

- The Assassination of an American Myth

- Burials and Border Crossings: Living the Dystopian Dream

- Back to Nature, or Forward to the Past: The End of the Quest

- Bibliography

- 10 Growing up in the New Age: A Journey into Wonderland?

- The Commune and the Letter: Where It All Began

- The Ark, Voices and Intertwining Strands: Using my Parents’ Writing in ‘Growing up in the New Age’

- Squatting as a Countercultural Activity and Life at 81 Thicket Road

- Kirkdale Free School and the Philosophy of Alternative Education

- Growing up in the New Age: Spiritual Emergency?

- Bibliography

- Part IV Outer Space

- 11 Alternative Worlds in the Cosmos

- Worlds in Outer Space

- Outer Spatial Practice

- Representations of Outer Space

- Artistic representations

- Space Art as ‘scientific’ representation

- ‘The Outer Space Frontier’ as a representation

- Representational Space: Towards Real Alternatives

- Acknowledgements

- Bibliography

- 12 Between Bauhaus and Bügeleisen: The Iconic Style of Raumpatrouille (1966)

- Straßenfeger (Blockbuster)

- The Stylistic Elements of a Cult Series

- Design Influences

- Objects of Desire and Control

- A Concrete Utopia?

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- 13 Blue Sky Thinking in a Post-Astronautic Present

- Escaping/Going Nowhere

- A Reconfigured Aristotelian Imaginary

- Seahaven’s Solid Sky

- The Ideal of Tativille

- A Frozen Sky

- A Breathless Edge

- Bibliography

- Film

- Websites

- Other sources

- Notes on Contributors

- Series Index

| vii →

Chapter 1

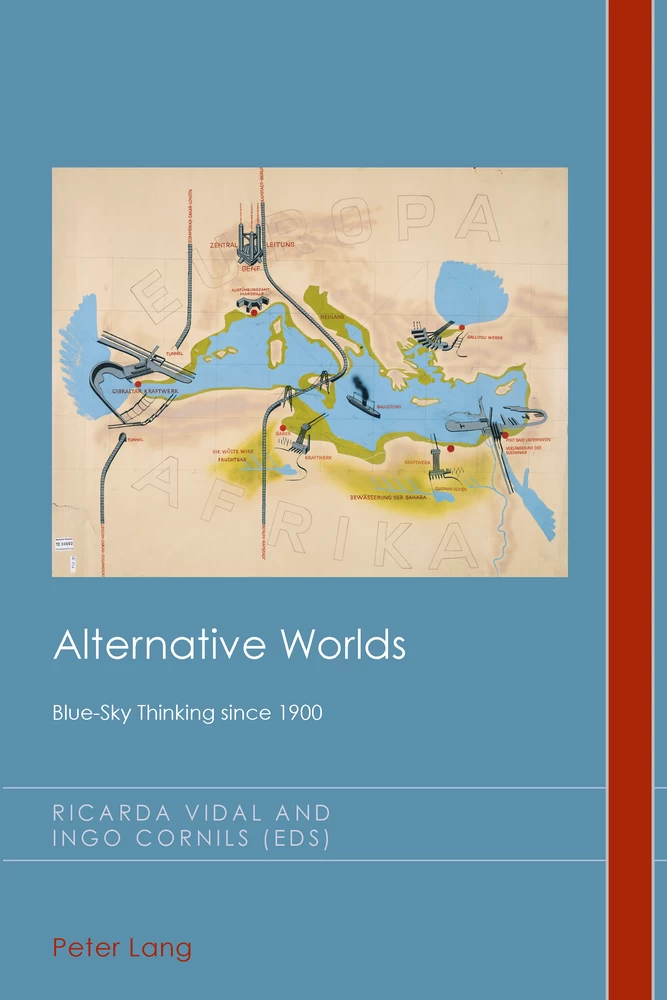

| Figure 1 | Herman Sörgel, Schaubild von Atlantropa (Map of Atlantropa), 1932 © Deutsches Museum Munich, archival signature: TZ 04602. |

| Figure 2 | Georg Ferber and Wilhelm Appel, aerial perspective of the New Genoa after the sea level has been lowered by 100 meters, 1932 © Deutsches Museum Munich, archival signature: TZ 04843. |

| Figure 3 | ‘Decline of the West – or Atlantropa as U-turn and new Goal’. Publicity material for Atlantropa, commissioned by Herman Sörgel with drawings by Georg Zimmermann. Herman Sörgel, Die drei großen ‘A’ (Munich: Piloty & Loehle, 1938), p. 42f, Fig. 20, 21. |

| Figure 4 | ‘A People without Space’ – ‘Space without a People’, Sörgel’s book Die drei großen ‘A’ (1938), p. 53. |

Chapter 2

| Figure 1 | Landscape near Sorbas (Andalusia, Spain) © Daniel Garcia-Castellanos. |

| Figure 2 | Artistic representation of the geography of the western Mediterranean during the isolation of the Mediterranean about 5.5 million years ago. Drawing: Pau Bahí. ← vii | viii → |

| Figure 3 | Valley excavated during the desiccation of the Mediterranean at the mouth of the Ebro River (Spain), as seen through the reflection of seismic waves. Author: Roger Urgelés. |

| Figure 4 | Geography of southern Spain and northern Africa during the period of restricted connections between the Mediterranean and the Atlantic, ca. 5.5 million years ago. Artist: Manuel Mantero. |

| Figure 5 | Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Running Fence, Sonoma and Marin Counties, California, 1972–1976, photo: Wolfgang Volz © 1976 Christo. |

Chapter 5

| Figure 1 | Ian Robinson, Russell, Crescents – Hulme, Manchester, 1978. |

Chapter 10

| Figure 1 | Kev & Anna, Anerley, 1979 © Dave Walkling. |

| Figure 2 | 81 Thicket Road and members of the commune © Dave Walkling. |

| Figure 3 | Growing up in the New Age: ‘Flower Child’ © Marjolaine Ryley. ← viii | ix → |

| Figure 4 | Growing up in the New Age: ‘Holy Man’ © Marjolaine Ryley. |

| Figure 5 | Growing up in the New Age: ‘Mushrooms and Sandbags’ © Marjolaine Ryley. |

| Figure 6 | Growing up in the New Age: ‘Forbidden Fruit’ © Marjolaine Ryley. |

Chapter 11

| Figure 1 | The Production of Space: Lefebvre’s Conceptual Triad.256 |

| Figure 2 | ‘Dreadful Sanctuary’ by Chesley Bonestell (1949). Reproduced courtesy of Bonestell LLC.260 |

| Figure 3 | ‘Saturn as seen from its satellite Titan’ by Chesley Bonestell (1950). Reproduced courtesy of Bonestell LLC.261 |

| Figure 4 | ‘Lunar Expedition in Sinus Roris’ by Chesley Bonestell (1953). Reproduced courtesy of Bonestell LLC.261 |

| Figure 5 | Wernher von Braun demonstrates a model Moon lander to Chesley Bonestell, c. 1952. Reproduced courtesy of Ron Miller.262 |

| Figure 6 | Space Art at the Frontier. A poster for Mars Society, 2003–2004 conference. Reproduced courtesy of Gus Frederick.269 |

| Figure 7 | ‘The Journey’ by Pat Rawlings (1994). Reproduced courtesy of NASA.271 |

| Figure 8 | ‘Pioneering the Space Frontier’ by Robert McCall (1986). Reproduced courtesy of McCall Studios.272 |

| Figure 9 | Cover of Astounding Science Fiction, April 1939. Painted by Charles Schneeman. ← ix | x → |

Chapter 12

| Figure 1 | The Orion. Film still from Raumpatrouille © Bavaria Film GmbH. |

| Figure 2 | On the Orion set © Bavaria Film GmbH.288 |

| Figure 3 | The Orion takes off. Film still from the opening sequence of Raumpatrouille © Bavaria Film GmbH. |

| Figure 4 | ‘Astro-design’. Film still from Raumpatrouille © Bavaria Film GmbH. |

| Figure 5 | The Orion crew. Film still from Raumpatrouille © Bavaria Film GmbH. |

| Figure 6 | Robots. Film still from Raumpatrouille © Bavaria Film GmbH. |

Chapter 13

| 1 →

In the spring of 2011, visual culture scholar Ricarda Vidal organised a seminar series at the University of London’s School of Advanced Study on the topic of ‘Alternative Worlds’. The series was conceived as an antidote to the then pervasive sense of gloom following the British government’s austerity drive in the wake of the global financial crash and as an opportunity to reflect on the many manifestations of ‘utopian desire’ in the twentieth century. The choice of the word ‘alternative’ rather than ‘utopian’ was deliberate, as it provided the freedom to step outside an established discourse. This volume is intended to bring the discussion to a wider audience.

It is no secret that utopian thinking has been in crisis for some time. As early as the end of the 1970s, Frank and Fritzie Manuel mused:

Are we witnessing a running down of the utopia-making machine of the West? Or is it only a temporary debility? Does the utopia of the counterculture herald an authentic rebirth? Must utopias henceforth be nothing but childish fairytales?1

Since then, utopian studies have become mainstream and have subsumed every ‘progressive’ political thought, practical action and literary imagination (including science fiction)2 under their paradigm. However, with the fall of communism and the rise of a global communication network utopians have been fighting a rear-guard action. Frederick Jameson acknowledges the challenges faced by the utopian ‘programme’ but insists that the ← 1 | 2 → utopian ‘impulse’ for radical change remains the only proper response to global capitalism:

Disruption is, then, the name for a new discursive strategy, and Utopia is the form such disruption necessarily takes. And this is now the temporal situation in which the Utopian form proper – the radical closure of a system of difference in time, the experience of the total formal break and discontinuity – has its political role to play, and in fact becomes a new kind of content in its own right. For it is the very principle of the radical break as such, its possibility, which is reinforced by the utopian form, which insists that its radical difference is possible and that a break is necessary. The Utopian form itself is the answer to the universal ideological conviction that no alternative is possible, that there is no alternative to the system. But it asserts this by forcing us to think the break itself, and not by offering a more traditional picture of what things would be like after the break.3

Similarly, Peter Thompson argues in his recent book on the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of the publication of Ernst Bloch’s The Principle of Hope that the world continues to require radical change:

In the context of the work of Ernst Bloch, the apparent loss of hope for change or improvement seems to have become a self-fulfilling and debilitating condition. […] [W]hat is at stake is not simply the daydream of how things could be better but the underlying principle of how things could be better and how hope functions in the world as a real latent force.4

Cultural critics like Jameson and Thompson maintain that unless we have an ideological superstructure to successfully create a better world, every effort to change, alter or improve it will be in vain. Thompson freely admits that humanity had taken a series of what he euphemistically terms ‘ideological or theological byways’, but claims that these were not always ‘blind alleys or dead ends’. While this may certainly be the case, several of the alternatives we are examining in this volume were thought up in deliberate opposition ← 2 | 3 → to ideology, and, in some cases, as outspoken alternatives to the essential unrealness of utopia.

Henk de Berg challenges the utopians’ belief structure and points out that cultural critics like Jameson or Thompson have little or nothing to contribute to the real existing problems the world faces today. He describes utopian thinking as misguided at best, and dangerous at worst.5 Indeed, the fundamental problem with the concept of utopia, the perfectibility of mankind, the striving for an ideal, is that it tends to turn good intentions into dogma. No matter how much scholars protest that utopias are not about an ideal,6 that is exactly how the wider public perceives it. Yet the more we want to reach an ideal state and tell ourselves that it can be reached, the more we deceive ourselves. Umberto Eco observes:

often the object of a desire, when desire is transformed into hope, becomes more real than reality itself. Out of a hope in a possible future, many people are prepared to make enormous sacrifices and maybe even die, led on by prophets, visionaries, charismatic preachers and spellbinders who fire the minds of their followers with the vision of a future heaven on Earth (or elsewhere).7

Utopian thinking, especially if it tends towards the grand ideologies, contains in it the seed of its own destruction.8 Following two world wars and the Cold War in the twentieth century, we have become wary of the utopian. This manifests itself in the increasing production of dystopian thought and writing. There is no shortage of utopia’s dark mirror, the dystopia. One look at recent science fiction films (Melancholia, dir. Lars von Trier, 2011; Hell, dir. Tim Fehlbaum, 2011; Prometheus, dir Ridley Scott, 2012; Cloud Atlas, dir. Tom Tykwer, Lana and Andrew Wachowski, 2013; Star ← 3 | 4 → Trek: Into Darkness, dir. J.J. Abrams, 2013; Oblivion, dir Josef Kosinski, 2013; Elysium, dir. Neill Blomkamp, 2013; After Earth, dir. M. Night Shyamalan, 2013)9 would convince any observer that we do not seem to expect much from the future.

If the ignominious demise of the grand utopian ideologies in the twentieth century has shaken our belief in collective fixes, the rapid global changes in trade, migration and communication have overtaken utopian thinking. The call for papers for the 2014 meeting of the Society for Utopian Studies puts it succinctly: ‘Utopias have nowhere left to hide in an era of global capital and information flows.’10 Similarly, a call for papers for the conference ‘Memories of the Future’ observes that the utopian imagination increasingly looks to the past for inspiration:

From our current ‘after the future’ position, where utopias have been crushed under the awareness that ‘the myth of the future is rooted in modern capitalism’ (Bifo), our imagination persistently draws on an extensive repository of symbols, forms and technologies rooted in history, imagination and memory.11

In her book Everyday Utopias: The Conceptual Life of Promising Spaces (2013), Davina Cooper suggests that utopian projects are increasingly attempted on a smaller scale. Yet herein lies the problem. Can we still subsume the ‘utopian desire’ under the umbrella of utopianism when it has been privatised and emasculated?12

Details

- Pages

- X, 333

- Publication Year

- 2015

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9783034317870

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783035306736

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783035397987

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783035397994

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-3-0353-0673-6

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2014 (December)

- Keywords

- economic crisis change alternative thinking

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, New York, Wien, 2015. X, 333 pp., 11 coloured ill., 23 b/w ill.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG