Commercial Integration between the European Union and Mexico

Multidisciplinary Studies

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the editor

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- Foreword

- The Impact of the EU-Mexican Trade Agreement on Revealed Comparative Advantage

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Review of Literature

- 3. Methodology and Data

- 4. Results

- 5. Conclusions

- References

- The EU-Mexico Agreement: What Has Happened to Trade and Capital Flows since 2000?

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Trade in goods

- 2.1 The EU total trade

- 2.2 Mexico’s total trade

- 2.3 EU-Mexico trade

- 3. Foreign Direct Investment Flows

- 3.1 The EU’s FDI

- 3.2 Mexico’s FDI inflows

- 3.3 Mexico’s reception of FDI by sector

- 3.4 FDI flows from the EU

- 4. Trade and FDI determinants

- 5. Conclusions

- References

- Mexican-European Union Free Trade Agreement: Liberalization Process and Mexican Export Performance

- 1. Introduction

- 2. General Characteristics of the Mexican – European Union Free Trade Agreement

- 3. Mexican-EU FTA Tariff Elimination Scheme for Mexican Products

- 4. MEX-EU FTA Commercial Liberation for Mexican Food Products

- 5. Mexican Exports to European Union before and after the Mexican-EU-FTA

- 6. Agro-Food Mexican Exports to the European Union

- 7. Mexican exports of processed food to the European Union (Section IV of the HS) before and after the Mexican-EU-FTA

- 8. Conclusions

- References

- Mexican Firms’ Entry Strategies to the European Union Market

- 1. Introduction

- 2. The European Union and Mexico Free Trade Agreement

- 3. Mexican Imports from the European Union

- 4. Mexican Exports to the European Union

- 5. Chapter objectives

- 6. Literature Review: International Strategies

- 7. Traditional Motivators in International Trade

- 8. New Motivators

- 9. The Meaning of Internationalization: Prerequisites and Processes

- 10. The evolution of a mentality: from an international strategy to a transnational strategy

- 11. The mode of entry strategies into the European Union by Mexican firms

- 12. Conclusions

- References

- The EU-Mexican FTA and Art. XXIV GATT

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Trade creation vs. trade diversion

- 3. Art. XXIV GATT

- 4. The external criteria: Art. XXIV:5b GATT

- 5. The internal criteria: Art. XXIV:8b GATT

- 6. The EU-Mexican FTA in the light of Art. XXIV GATT

- 6.1 The CRTA

- 6.2 Trade Data

- 7. Conclusions

- References

- Investment Protection Standards in the Mexico – European Union Bilateral Investment Treaties: Fair and Equitable Treatment and Full Protection and Security

- 1. Introduction

- 2. The new EU investment policy

- 2.1 General Framework of the new policy

- 2.2 Evolution of investment regulation in the EU

- 2.3 BITs Concluded by EU Member States prior to the entry into force of the Treaty of Lisbon

- 2.4 BIT Arbitration under the proposed regulation

- 2.5 Substantive investment protections under the new investment policy

- 3. Fair and Equitable Treatment in the context of the Mexico-EU BITs

- 3.1 General notion of FET

- 4.3.1 The interpretation of FET in accordance to international law principles

- 3.1.2 The interpretation of FET as a standard linked to customary international law

- 3.1.3 The interpretation of FET as a self-contained standard

- 3.1.4 Tecmed

- 3.2 The relationship between FET and other standards of investment protection

- 4. Full Protection and Security

- 4.1 FPS linked to Customary International Law

- 4.2 FPS as a self-contained standard

- 5. Conclusions

- References

- Cases

- Treaties

- Reputations and Supportive Behavior of Spanish and U.S. Firms in Mexico

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Hypotheses

- 2.1 Foreign Headquarters

- 2.2 Degree of Internationalization

- 2.3 Individual-Level Demographic Influences

- 2.4 Supportive Behavior

- 3. Methodology

- 3.1 Sample

- 3.2 Dependent Variables

- 3.3 Independent Variables

- 3.4 Control Variables

- 3.5 Analysis

- 4. Results

- 4.1 Corporate reputation

- 5. Supportive behavior

- 6. Discussion

- 7. Conclusions

- References

- Regulatory Changes of the Financial Industry in the E.U.

- 1. Introduction

- 2. The origins of the 2007-2009 financial crisis in the United States

- 3. The European Union’s Financial Regulation Framework: Some Antecedents

- 4. The First Bank Directive

- 5. The Second Bank Directive

- 6. The Investment Services Directive

- 7. The Capital Adequacy Directive

- 8. Financial Services Action Plan

- 9. The Commission of Wise Men and the Lamfalussy Report

- 10. Why did the existing regulations fail in 2007-2009?

- 11. The integration of the financial markets in Europe, national regulations and the convergence efforts

- 12. The Larosière and Turner Reports

- 13. Lord Turner’s Report

- 14. Concluding Remarks

- References

- An Approach to the CSR of European Companies Operating in Mexico

- 1. Introduction

- 2. European and Mexican Conceptions of CSR

- 3. The Millenium Development Goals (MDG) as Reference for CSR in Mexico

- 4. The Stakeholders’ Role in Defining CSR Objectives

- Spanish Companies in Mexico and their CSR

- 5. BBVA

- 6. Santander

- 7. Gas Natural Unión FENOSA

- 8. Gas Natural Mexico

- 9. Telefónica

- 10. Sol Melia

- 11. CSR of Spanish Companies in Mexico in the EUMFTA framework

- 12. Conclusion

- References

← 60 | 61 → Mexican-European Union Free Trade Agreement: Liberalization Process and Mexican Export Performance

Sergio Ortiz Valdés

1. Introduction

In recent years, Regional Trade Agreements (RTAs) have been multiplying and becoming an important trend in world economy (Ghosh C. & Yamarik. 2005). According to WTO, in 1990 only 107 RTAs were registered at the organization and by December 2008, 421 RTAs were notified. Of this number, 90% are partial-scope free trade agreements (FTA) and approximately 10% accounted for customs unions1. This proliferation of RTAs is influenced by the lack of substantial advances in the Doha Round of the World Trade Organization (WTO), given by the complexity processes to negotiate bilateral agreements as opposed to multilateral agreements.

The proliferation of RTAs has led to discussion based on the real impact on trade and well-being effect of these treaties. Robinson and Thierfelder (2003) argue that RTAs have had a positive effect on welfare, besides there is supporting evidence submitted by investigations that showed a dominance of trade creation over trade diversion. In contrast, Bhagwati and Kruger (1995) and Bhagwati and Panagariya (1996) question the efforts to negotiate increasing RTAs, but the real outcomes seem to be uncertain. This argument is consistent with the vision of Economics Nobel Laureate, Joseph Stiglitz who holds that Free Trade Agreements are meant to eliminate tariffs, quotas, restrictions and subsidies, but in reality things are different, and they are affecting some sectors in developing countries that benefit from other countries sectors as well.

In addition, he states that the real consequences in Latin America, are quite negative, because of the fundamental principle of non-discrimination that has been neglected, causing that Free Trade Agreements in the continent are neither free, nor fare (Stiglitz, 2006).

← 61 | 62 → On the other hand, 2009 Economic Nobel Laureate, Paul Krugman argues that RTAs increase well-being and improve consumption capacity. They are crucial strategies to increase business competitiveness and therefore substantial improvements in industrial specialization in the countries involved (Krugman 1993). RTAs represent a “new regionalism” that complements the multilateralism where developing countries enter trade schemes traditionally dominated by developed countries (Ethier, 1998).

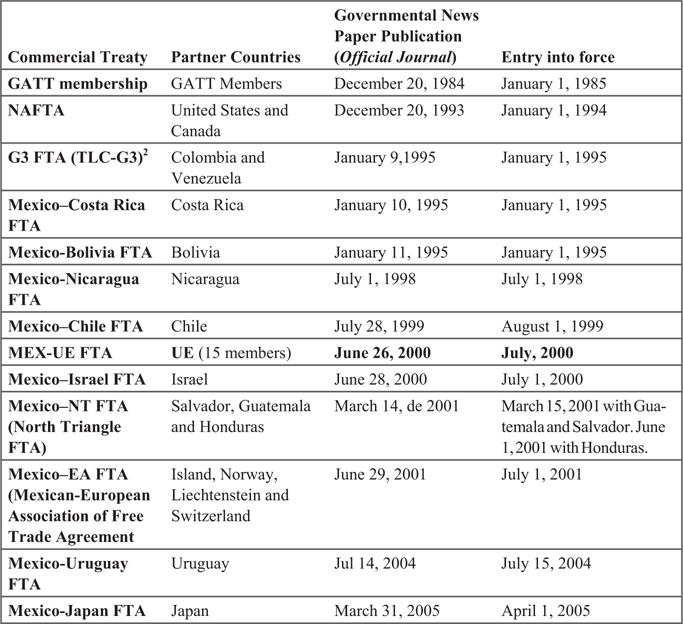

Mexico has been one of the countries particularly prolific in the negotiation and implementation of free trade agreements (FTA), transforming from one of the closest economies in the world, practically without any commercial agreements, to one of the economies with more free trade agreements worldwide. During the period of 1994-2005 Mexico signed 12 FTAs, including the Mexican-European Free Trade Agreement.

In terms of Mexican diversification exports, FTAs have not been successful tools as expected. The present chapter includes a portrayal of the Mex-EU FTA characteristics, including a description of the liberalization process for industrial and agricultural industries. Besides it is also analyzed the real commercial benefits for Mexico and trend examination of the Mex-EU FTA before and after the commercial agreement. Finally, this chapter will focus on detail in the agricultural sector.

2. General Characteristics of the Mexican – European Union Free Trade Agreement

According to the original text “Globalization for All: The EU and World Trade: Europe in Movement”, published by the Directorate General of Press and Communication for the European Commission in 2002, the EU first 15 Members represent only 6 % of world population, and more than 20 % of international trade, making the EU one of the major commercial players in world trade. Given the economy’s size and its consumption capacity, it is easy to visualize the importance of this region for Mexico.

In Brussels, on December 8 of 1997, the “Economic Association Agreement and Political Cooperation (Acuerdo de Asociación Económica, Concertación Política y Cooperación) was signed between Mexico and the 15 members of the European Union. However, it was not until February 23 in Lisbon and on February 24 in Brussels of 2000, that the European Council approved the agreement. In Mexico, the agreement was signed by the Senate Chamber on March 20 of the same year. In this document was stated that the Mexican-European Free Trade Agreement (Mex-EU FTA) would enter into force on July 1, 2000. This agreement replaced the Framework Cooperation Agreement (Acuerdo Marco de Cooperation) between Mexico and the European Community signed in Luxembourg on April 26, 1991.

← 62 | 63 → By 2000, Mexico had already signed six FTAs including the North America Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). However, with the European Union, Mexico negotiated a much broader agreement. Besides there are some aspects usually negotiated in FTA’s such as the removal of trade tariffs, investment and the movement of capital, competition, national treatment to service providers, intellectual property, among others; this FTA included other features like economic and political cooperation topics, cooperation for scientific and technological research in different sectors, cooperation for the establishment and strengthening of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), including the creation of funds for this purpose, also cooperation in the field of training and education and social affair, strategies to overcome poverty and finally cooperation on human rights, democracy and health.

Unlike previous FTAs signed by Mexico, this agreement dealt with economic and politic cooperation in an attempt for a stronger Mexican integration with the world. The negotiations of this agreement, contemplated three elements: (1) trade of goods and services, (2) economic cooperation for development, and (3) political cooperation and democracy. Because of the latter two elements, this agreement is considered an “Agreement of Economic Partnership” (Acuerdo de Asociación Económica) in which, the FTA is only one of the three components of the Mexican-European Union Agreement of Economic Partnership. Nevertheless, the purpose of this work is to describe and analyze the commercial component, focusing on the analysis of the commercial performance, particularly the Mexican Exports to the EU.

Mexican and European Union representatives, agreed to establish a free trade area within a maximum of ten years since the entry into force of the agreement. In spite of this period established in the Mexican-EU FTA negotiation, the EU eliminated most of the customs tariffs on imports from Mexico in 2003, while Mexico eliminated most of the custom tariffs on imports from the EU in 2007. For the European Union, the benefits of the agreement should be the same, as those established with the NAFTA partners.

Source: Mexican Secretary of Economy (Secretaría de Economía de México), 2009

← 63 | 64 → Nonetheless, in other cases of FTAs, a Joint Council (JC) was established between the two governments of this agreement; it was charge of negotiating and monitoring processes. In addition, the JC elaborated eleven chapters as core references for different interest groups in Europe and in Mexico. These chapters became the main framework for the negotiation process due to the domestic concern expressed by both parts involved. It is important to mention, that the JC also established different bi-national commissions, such as agriculture, auto parts and electronic among others. Nevertheless, in any other FTA, the Commission based the product liberalization process on the Harmonized System (HS)3.

← 64 | 65 → Here are presented the chapters of the Mexico-European Union Free Trade Agreement:

1. Market access

2. Rules of origin

3. Technical norms

4. Sanitary norms and certification

5. Safeguards

6. Investment and related payments

7. Services trade

8. Government purchases

9. Competitiveness

10. Intellectual property

11. Dispute settlement

For the trade liberation process, the Mexican-European bi-national commissions conducted an analysis of the Harmonized System (HS) classification to address categories for each product. These categories were represented by numbers and letters for all products subject to trade between the European Union and Mexico. Industrial products were categorized by letters; and agricultural, farming and fishery products by numbers. Depending on the situation, this classification and product analysis was made according to economic and political interests of the parties, besides it serves as the basis to negotiate the tariffs and in most cases its elimination. In the case of Mexico, its representatives established letters “A”, “B”, “B +” and “C” to categorized all industrial, manufactured and mineral products; in other words, this classification was used for all those products that are not cataloged ad agricultural and fishery products.

For those products (industrial, manufactured and mineral products) European representatives established only two categories: “A” and “B". Therefore, in the European market, all products not classified as agricultural, farming or fishery goods, have only two schemes of tariff reduction, while in Mexico they have four.

The first four sections of the HS refer to agricultural and farming products, including chapters 1 to 24. These products were classified into seven categories, also listed by numbers. As it can be seen there are more categories in this kind of products due to their important political influence, complex negotiation process, and classification possibilities that respond to different economic and political sensitivities.

Details

- Pages

- 242

- Publication Year

- 2014

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783653037340

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783653991314

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783653991321

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9783631648315

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-3-653-03734-0

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2014 (June)

- Keywords

- Freihandel North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) geopolitische Interessen Handelsverkehr Wirtschaftliche Integration Geldverkehr

- Published

- Frankfurt am Main, Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Wien, 2013. 242 pp., 35 tables, 34 graphs

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG