Battleground Bodies

Gender and Sexuality in Mozambican Literature

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: An Iron House: Approaching Gender and Sexuality in Mozambique

- Chapter 1: Boundaries, Borderlands and Bodies: Gender and Sexuality in Mozambique’s Long Twentieth Century

- Chapter 2: Unma(s)king Hegemony: Negotiating Masculinities in José Craveirinha and Paulina Chiziane

- Chapter 3: Strategies of Disidentification: Rewriting Femininity in Noémia de Sousa and Ungulani Ba Ka Khosa

- Chapter 4: States of Exception: Suicide, Hunger and Haunting in Lília Momplé and Suleiman Cassamo

- Conclusion: Firing Lines

- Bibliography

- Index

- Series Index

This book began its official life as a PhD thesis, completed at the University of Manchester. The inspiration for it, however, began to emerge the moment I entered the undergrad classroom of one Professor Hilary Owen, whose teaching first introduced me to the histories and cultures that would ultimately shape my career. For this, and for her inimitable intellectual and moral support through eight years of study and beyond, I give her my greatest thanks. My thanks also go to Lúcia Sá and Chris Perriam, both of whom were invaluable sources of encouragement, enthusiasm and evaluation throughout the PhD process.

Warm thanks to Rhian Atkin, who showed me that research was my path, convinced me I had something to contribute, and has supported me to do just that ever since – through degrees, submissions, peer reviews, job interviews and the pitfalls of early career research, and sometimes just through a bottle of wine. I must likewise thank David Frier, Carmen Ramos-Villar and Mark Sabine, all of whom have been endlessly generous with time, advice and opportunities, and my Portuguesistas-in-arms, Anneliese Hatton, Emanuelle Santos and Deborah Madden. For their meticulous review of the manuscript and for offering to publish the book as part of their series with Peter Lang, many thanks indeed to Paulo de Medeiros and Cláudia Pazos-Alonso.

In the summer of 2014 I was lucky enough to travel to Maputo for four weeks to rifle through archives and libraries and to purchase my bodyweight in books, a trip financed by the AHRC and the University of Manchester School of Arts, Languages and Cultures. Professor Nataniel Ngomane of the Universidade Eduardo Mondlane offered fantastic guidance on navigating the city before and during the trip, and the technicians at the Arquivo Histórico truly went above and beyond to help me find what I needed – walking me halfway across the city to find one dusty 1985 copy of Notícias was a particular highlight. For helping me to scratch under the surface of this beautiful city, thank you all. ← vii | viii →

I completed this book during the first year of a lectureship at the University of Southampton, where I have been generously supported by my colleagues; in particular, I wish to thank Sophie Holmes-Elliott, Dan Finch-Race, Mimie Morin, Jaine Beswick, Tony Campbell, Marion Demossier, Scott Soo, Aude Campmas and Vivienne Orchard, and honorary department member Lucy Holmes-Elliott.

For the company, gossip, lunch breaks and celebrations, many thanks to the extended family of the Ellen Wilkinson building – especially, in no particular order, Joe, Kaya, Janek, Nikki, Jess, Gwynne, Lynda, Joaquín and Lucía. Also responsible for keeping me sane, with (variously) cats, wine, sitcoms, visits, phone calls and Travelodge trips, are Lou, Simon, Ellie, Zoë, Katherine, Jules and Wadoud.

Thanks to all at Peter Lang Oxford for making the publication of the book such a smooth process.

Finally, I must thank my wonderful family – Sal, George and Max – for their unconditional love, support and motivation.

This book is dedicated to my favourite bruxas, Mary Farrelly and Maria Montt. Thank you for everything.

An Iron House: Approaching Gender and Sexuality in Mozambique

In the heart of urban Maputo, halfway between the modern skyline of downtown and the uphill sprawl of residential neighbourhoods, stands an unusual building. At odds with the colonial grandeur, Soviet minimalism or capitalist gleam that characterize the bulk of the city’s architecture, the building is unique, made not from stone, concrete or weatherboard, but of neatly stacked geometric iron panels. The popular legend behind Maputo’s ‘Casa de Ferro’ [Iron House], repeated ad libitum by tourist guides online and in print, is that it was designed by Gustave Eiffel himself, and commissioned in the early 1890s by Mozambique’s Governor General to serve as his place of residence in the city, then known as Lourenço Marques. Having never set foot in Mozambique, however, Eiffel had failed to take the country’s tropical climate into account, and the newly constructed Iron House turned out to be too hot inside to inhabit (Briggs n.d.; Fitzpatrick et al. 2013: 149; Slater 2013: 39).

The House’s official history is both more complex and less certain. An 1895 study by Eduardo de Noronha, tasked with organizing the district’s governmental archive in 1880, states that the House was indeed commissioned by the Portuguese colonial government as a place of residence (108). The reason for choosing the design, Noronha affirms, was one of fashionable caprice, inspired by the craze for Belgian-manufactured prefabricated iron houses in the Congo (108). It was brought in pieces from Belgium to Mozambique, along with two construction workers to put it together (108). Eiffel, meanwhile, is nowhere to be seen. He is similarly absent from the 1966 account of Lourenço Marques’s historical buildings authored by historian and travel writer Alfredo Pereira de Lima, who concurs with Noronha’s implication that the House, once built, was rejected as ← ix | x → a governmental residence on the basis of aesthetics rather than pragmatics (59); neither account mentions the climate as a deciding factor.

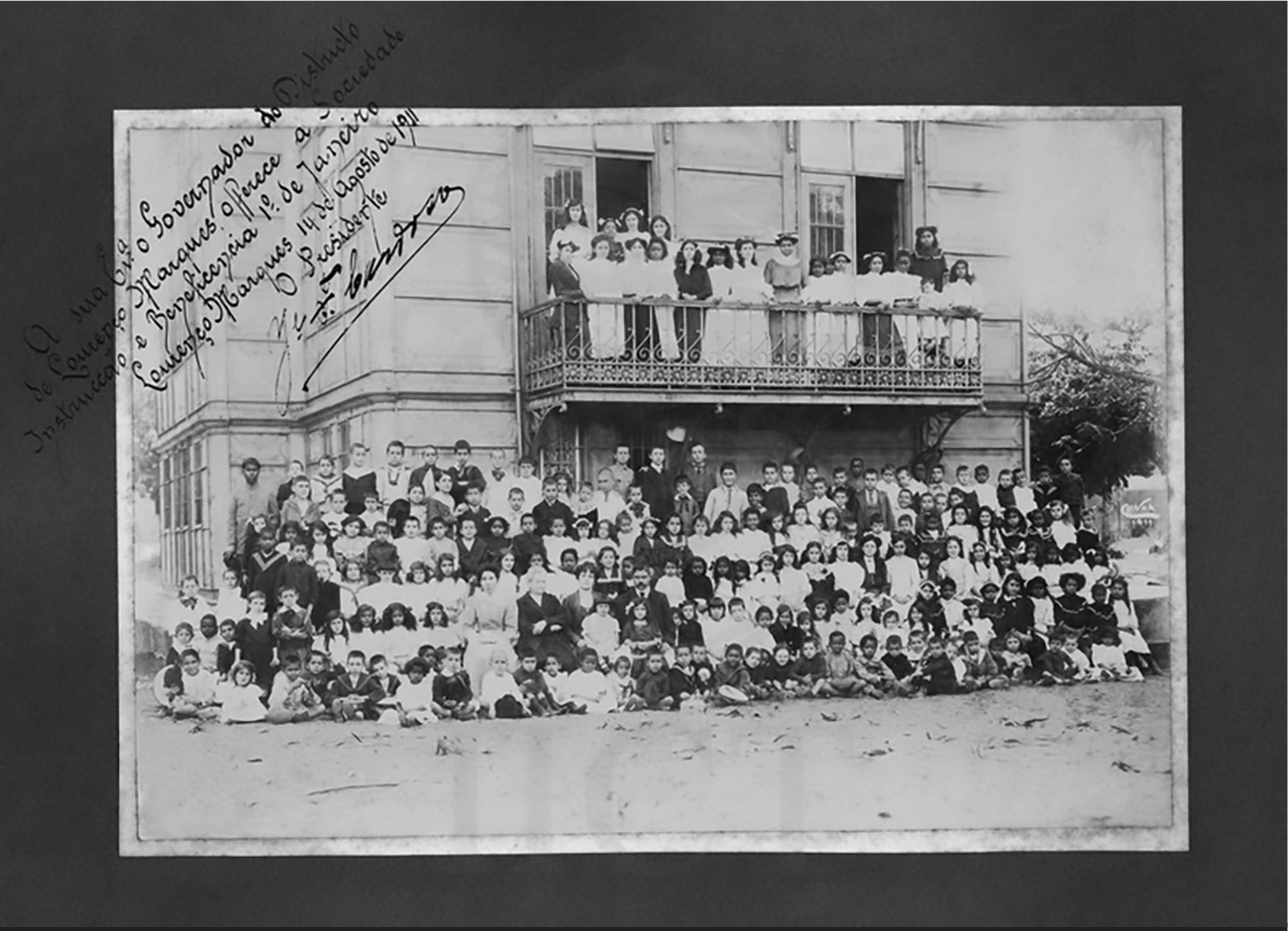

Following its abandonment as a place of residence, both sources agree that in 1893 the Governor-General, Rafael de Andrade, donated the unwanted building to the Bishop of Mozambique António Barroso, who repurposed it as a girls’ school run by missionary nuns: the Instituto de Ensinho Rainha D. Amélia. Noronha waxes lyrical about the institution, lauding the nuns for their ‘affectuoso trato, que não conhece raças nem distingue cores’ [affectionate demeanour, which knows neither race nor colour] and for saving their young charges from a hitherto inevitable lifetime of ‘boçal ignorância’ [rude ignorance], transforming them into ‘seres aproveitáveis, que serão um dia mães, e que ensinarão aos filhos o amor por nós, amor que lhes foi inoculado pela catequese sensata e meiga das caritativas senhoras’ [productive beings, who will one day be mothers, and who will teach their children love for us, a love instilled in them through the sensible and kindly catechism of these charitable ladies] (167).1

Upon entering the school, Noronha describes with some enthusiasm the diverse ethnicities of its pupils, whose faces appear as ‘um tapete matizado das mais caprichosas cores; ali uma pretinha retinta, aqui uma mulata, acolá uma mestiça, alem uma india, mais perto uma chineza’ [a carpet dotted with the most whimsical of colours; there a little dark black girl, here a mulatta, over there a mestiça, over yonder an Indian girl, nearby a Chinese girl] (167). He experiences ‘uma recordação vaga da familia, uma saudade intensa das caricias que nos fizeram a pequenos’ [a foggy memory of family, an intense nostalgia for the caresses that are given to us as children] (167), and leaves the school convinced that the women in charge, ‘tendo por norma o progresso, por bordão a crença, por alvo a civilisação, valem mais do que todo um exercito’ [having progress as their rule, faith their tool, and civilization their aim, have more worth than an entire army] (168).

This saccharine vision of racial harmony is where the story of the Iron House ends for Noronha. Thanks to Lima, we learn that following the fall of the Portuguese monarchy in 1910, the school was shut down and ← x | xi → passed over to the Sociedade de Instrução e Beneficiência 1º de Janeiro, who reopened it as a mixed-sex school (1966: 65), a point confirmed by a 1911 photograph of the House marked with the school’s name, held by the Instituto de Investigação Científica Tropical (see Figure 1). In 1912 the school moved buildings, and in a later volume, first published in 1968, Lima notes that its erstwhile home now belongs to the government’s Geography and Mapping Department (67). An unpublished doctoral thesis by Pedro Guedes includes a photograph of the House, taken in 1972, still in its original location. By 1987, the date given for another photograph appearing in a 1997 Nelson Saúte text commemorating Portuguese expansionism (39), the House has been dismantled and moved to where it stands today: within sight of the colossal statue of Samora Machel that looks out on downtown Maputo, and just off the busy avenue that bears his name. It houses some archival material, and serves as a tourist curio.

Figure 1: Children standing in front of the Iron House, which by now (1911) housed a mixed-sex school known as the ‘Sociedade Instrução e Beneficiência 1.º Janeiro’. Author unknown; held by the Instituto de Investigação Científica Tropical, Lisbon. ← xi | xii →

The story of the Iron House functions as an unexpected yet rich starting point for approaching the role of gender and sexuality in the history and cultural output of late colonial and post-independence Mozambique. On a pragmatic level, it underscores the necessity, for those wishing to understand recent Mozambican history, to return to a broad patchwork of primary sources, to interrogate historical narrative, and to pay attention to silence and absence. From a perspective of cultural history, Noronha’s account in particular provides vital insights into the romanticization of the Portuguese colonial presence in Mozambique by those who upheld it. His portrayals of the pupils at the Instituto de Ensinho Rainha D. Amélia additionally exemplify the enduring colonial fantasy of the female body as the site of regenerative national unity, which itself anticipated the racialized permutations of that vision that would emerge following the Portuguese government’s espousal of Lusotropicalism five decades later.

Details

- Pages

- XXXVI, 214

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781787075979

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781787075986

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781787075993

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781787073173

- DOI

- 10.3726/b11524

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2017 (May)

- Keywords

- Mozambican literature Gender and sexuality Critical theory

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, New York, Wien, 2017. XXXVI, 214 pp., 3 b/w ill.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG