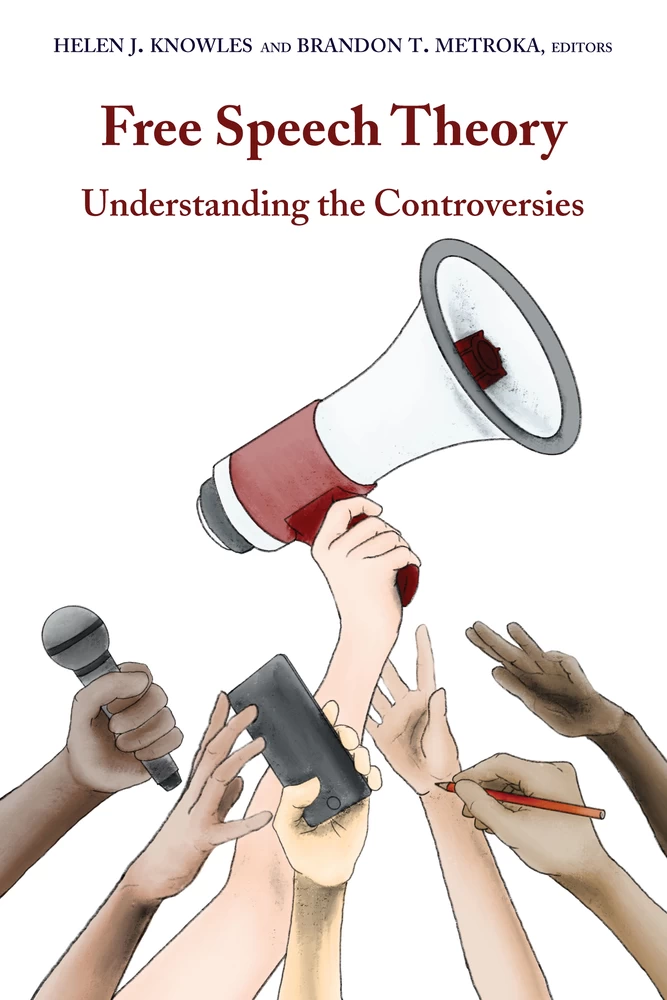

Free Speech Theory

Understanding the Controversies

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the editors

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Why Free Speech Theory Matters (Helen J. Knowles and Brandon T. Metroka)

- 1. No Neutrality: Hobbesian Constitutionalism in the Internet Age (James C. Foster)

- 2. Freedoms of Speech in the Multiversity (Mark A. Graber)

- 3. Free Speech, Free Press, and Fake News: What if the Marketplace of Ideas Isn’t About Identifying Truth? (Keith J. Bybee and Laura E. Jenkins)

- 4. Free Speech and Confederate Symbols (Logan Strother and Nathan T. Carrington)

- 5. Speech and National Past Times: The NFL, the Flag, and Professional Athletes (Aaron Lorenz)

- 6. The Slants and Blurred Lines: The Conflict Between Free Speech and Intellectual Property Law (Jason Zenor)

- 7. Free Speech Debates in Australia: Contemporary Controversies (Katharine Gelber)

- 8. Parliamentary and Judicial Treatments of Free Speech Interests in the UK (Ian Cram)

- Conclusion: It’s Still Complicated (Helen J. Knowles and Brandon T. Metroka)

- Contributors

- Index

- Series index

“Variety’s the very spice of life, That gives it all its flavour.”1 Without our dedicated contributors, this volume would not exist. Just like the proverb suggests, they have given this book life by providing us with an eclectic and engaging variety of perspectives on using theories of expressive freedom to understand contemporary free speech controversies. There is no one (right or wrong) way to approach the subject, and the chapters that follow reflect that belief. They do not obey a specific pattern or appropriate one single method of organization, and they do not apply the same theories in the same manner. This, we believe, is one of the strengths of this book. The diversity of the chapters embraces and reflects the truth of Archie Bland’s words, the words of the epigraph with which we open this book: “Practical freedom of speech, graduate-level freedom of speech, is not a black-and-white issue, not just a matter of misquoting Voltaire; it is a subtly calibrated scale. It involves questions about social context, and discretion.”2 Our contributors ask many questions, and provide some theory-grounded answers, all of which take social context and discretion very seriously. We are exceptionally grateful for their hard work.

The gratitude of the editors and contributors alike extends to Nick Stubba and Linda Tettamant for the work they undertook for us. Nick is a very talented SUNY Oswego alumnus (‘19) who did the detailed, laborious, and absolutely essential work (all while completing his undergraduate studies) of checking the accuracy of all of the quotations included in the book. Linda performed the Herculean task of casting her careful copyediting eye over the entire manuscript. Whatever errors remain are, of course, the sole responsibility of the editors and contributors alike.

We also extend our very sincere thanks to the Institute for Humane Studies for awarding us a Hayek Fund for Scholars Grant that enabled us to ←xi | xii→hire Nick and Linda. In particular, we are grateful to Tommy Creegan at the IHS, and Julie Marte and Michele Frazier at SUNY Oswego, for helping us with the paperwork related to the administration of this grant.

Although Helen daily finds herself herding four cats (and one horse), she considers that task infinitely easier than editing a book. Therefore, she is exceptionally grateful that Brandon agreed to sign on to this project. He truly picked up the slack when she could not (especially after emergency surgery left her without the normal use of her dominant hand for an extended period of time). Thank you, Brandon, for being a wonderful co-editor. I have enjoyed this journey!

Of course, it would be remiss of Helen not to mention, very quickly, that she is also very grateful to the aforementioned menagerie—Doc (neigh), Clementine, Smokey, Faith, and Toffee (meow, meow, meow, meow)—for their love and support (special credit goes to Toffee who repeatedly donned the editor-in-chief cap when he thought Brandon and Helen were going astray). Last, but by no means least, Helen owes everything to John, who is never short of something to say about free speech, and is never short of love to give to Helen. She dedicates this book to John, and to the memory of Jenny, the stepdaughter, who on July 5, 2019, was taken from this world far, far, far too soon.

Brandon extends his appreciation and gratitude to his family for their love, laughs, and encouragement: Cynthia & Sean; Robert & Sue (and Dalton); Ryan & Christen; Blaise & Brittany; Riana (and Brydon!); Kathy & Gary; Donna & Charlie; and many others. He is also appreciative of the support of numerous individuals who influenced and supported work contributing to this volume’s completion, including incredible colleagues Lydia Andrade and Scott Dittloff at the University of the Incarnate Word; Robert & Lisa Matson, Jim Alexander, and Ray Wrabley at the University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown; Tom Keck and Keith Bybee at Syracuse University; Craig Warkentin and Helen Knowles at SUNY Oswego; the talented staff at each of these institutions (including Candy Brooks, Jacquie Meyer, Sally Greenfield, Kelly Coleman, and Bethany Walawender at Syracuse; Lisa Teters and Patti Tifft at Oswego; and Lorraine Ewers, Rosalinda Villarreal, Kathy Allwein, and Matt Gonzalez at Incarnate Word) and Peter Lang Publishing; those offering critiques and feedback at regional conferences on earlier work on this subject; the contributors to this volume; and the many students he continues to teach and learn from. Most importantly, completion of this project would not have been possible without the friendship, love, and support of Adam E. Brnardic ←xii | xiii→(and Katie!); Zachary R. Cacicia (and Kayla!); Ron J. Gathagan (and Linh!); Brandon M. Miller; Brad S. Penrose (and Tiff!); and Jason A. Piccone.

HJK, Clinton, NY

BTM, San Antonio, TX

Note←xiii | xiv→ ←0 | 1→Notes

1 1. William Cowper, The Task and Other Poems (1899), last accessed July 13, 2019, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/3698/3698-h/3698-h.htm

2 2. Archie Bland, “Freedom of Speech: Is It My Right to Offend You?” Independent, February 2, 2014, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/freedom-of-speech-is-it-my-right-to-offend-you-9101650.html

Introduction: Why Free Speech Theory Matters

Helen J. Knowles and Brandon T. Metroka

As David Gilmour’s iconic Pink Floyd song, “Lost For Words,” suggests, it is neither healthy nor productive to try and respond to the words and ideas with which one disagrees by developing a “tunnel vision” of “spite.”1 If we simply attempt to shut (or, perhaps, shout) down our opponents by labeling them as “wrong” or “fake,” we ultimately create an impoverished, unproductive, and undemocratic dialogue. This is because when we allow ourselves to become cocooned within a world of free speech defined by nothing more than speech on our terms, we rarely (if at all) stop to think (because we do not have to) about why we value our particular viewpoints or why we are free to hold and express them. Consequently, we believe we are at liberty to ignore the effects of our speech on those around us.

If we do stop to consider those effects, we will not be able to fully comprehend their origins and meanings unless we acknowledge the value of the competing perspectives. Indeed, invoking “free speech” as an authority for a preferred political position is a form of question begging, because it assumes that a rhetorical appeal to a value alone (here, free speech) somehow decides a particular issue. The contributors to this volume provide analyses of particular “free speech” conflicts with the specific goal of critically assessing why and how “free speech” might resolve a particular conflict. Their chapters are united by the belief that the incantation of “free speech” is a starting point rather than the end game of any argument, and that normative inquiries—establishing “rules or ideal standards” for deciding what ought to be—need to be part of the expressive freedom conversation.

Within the realm of free speech, all of the chapters address the following inquiry: “How can we answer the question of how things ought to be?” ←1 | 2→Jonathan Wolff provides an answer to this question that speaks to the goal of this volume:

The uncomfortable fact is that there … [are] no easy answer[s]. But, despite this, very many philosophers have attempted to solve these normative political problems, and they have not been short of things to say … philosophers reason about politics in just the way they do about other philosophical issues. They draw distinctions, they examine whether propositions are self-contradictory, or whether two or more propositions are logically consistent … In short, they present arguments.2

The contributors to this volume pick up where too many citizens and pundits have left off—they present arguments that examine modern political controversies through different normative lenses, magnifying the assumptions that underlie shouts of “free speech!” They share a belief that in order to appreciate why free speech is relevant when deciding political controversies, one must first examine why free speech is valuable.

We view this problem on two different levels. First, such considerations get lost in the shuffle when one rejects the value of “disapprov[ing] of what you say, but … defend[ing] to the death your right to say it.”3 In the United States in the 21st century, there are disturbing signs that many in society are indeed willing to distance themselves from a commitment to tolerate diverse views. They seem ready to reject the profound statement made by Justice William J. Brennan, Jr. in his opinion for the U.S. Supreme Court in Texas v. Johnson (1989). Striking down a state law prohibiting flag desecration, Brennan wrote: “We can imagine no more appropriate response to burning a flag than waving one’s own, no better way to counter a flag burner’s message than by saluting the flag that burns…”4 This message of tolerance appears to have fallen on deaf ears, across the political spectrum. It is our collective belief that the true value of expressive freedom—which means more than just having the freedom to shout loudly at (or over) one’s perceived opponents—can best be understood by using prominent philosophical approaches to unpack contemporary free speech controversies (controversies which all too frequently involve inadequate doses of tolerance).

An example of a controversy which has developed in recent years, and which would benefit from being put under this free speech theory microscope, is the propensity of many (predominantly liberal) administrators on college campuses to (strongly) encourage their faculty to use “trigger warnings” to alert students to the presence, in course material, of controversial subject matter that might offend and/or psychologically injure students. Rather than defend the concept of a classroom as a vibrant debate forum, it is suggested to educators that they either eradicate (aka censor) ←2 | 3→certain “non-conforming” viewpoints, or discuss them with caution and/or disdain. In his welcoming letter to incoming students, John Ellison, dean of students at the University of Chicago, denounced this practice as a threat to “our commitment to freedom of inquiry and expression.”5 Other conservatives and self-described “classical liberals” have expressed this concern less kindly, indicting American universities for subverting a value long thought to be a “lodestar” of democracy. Terms like “regressive left” and “authoritarian” have been wielded as scythes against various constituent parts of this nebulous evil that seeks to destroy the lifeblood of a democratic body politic.6 Take, for example, the words of Dennis Prager, a conservative commentator and talk show host, who lambasts the idea of campus “safe spaces”:

The worst offenders in protecting free speech are professors, and deans, and presidents of colleges. It’s a moral cesspool, our university. And unless we are prepared to say that over and over, because just like big lies get believed, so do big truths. This is a big truth: the university in America is a wasteland—it is a moral and intellectual wasteland. It is the center of American hatred, of Western civilization hatred.7

Critics like Prager see political correctness run amuck; they believe that academics and others are either systematically or unwittingly (it is tough to tell which, at times) allowing good intentions to guide society down a primrose path to totalitarian hell.

Blind spots abound in this free expression debate. While vociferously denouncing the perceived elevation of “liberal” ideas in the university, many members of the “conservative” vanguard were noticeably silent over such matters as the suspension and subsequent resignation of Drexel University Associate Professor George Ciccariello-Maher, who first came under fire in 2016 for a “tweet” (that he described as satirical) which said “All I want for Christmas is white genocide.”8 A 2018 article in the Chronicle of Higher Education provides a number of examples of conservative efforts to silence or deter liberal speakers on college campuses, suggesting the double-standard accusation levied against the political left could apply in equal force to the political right.9 Similarly, there has been a remarkable lack of outrage from self-appointed free expression guardians in light of some local efforts to have books featuring LGBTQ characters removed from libraries, and in the aftermath of a Florida law that, until struck down by the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals, prevented doctors from discussing guns with patients in the course of standard inquiries about risks to safety and health.10 This sort of tunnel vision gets us nowhere. If we stop to ask why people engage in such expressions (and use theories to structure that inquiry), rather than uncritically ←3 | 4→embracing or rejecting their positions, our understanding of the dialogue will be that much richer.

We do caution, however, that as much as we believe such theoretical inquiries are needed, we do not believe that the sky is falling. The United States is no stranger to private and public challenges to expressive freedom. From the Sedition Acts of 1798 to the anti-communist sentiment of World War I, from the southern gag orders on discussions of slavery in legislatures to the tarring and feathering of Jehovah’s Witnesses during World War II (and beyond), the graveyard of American history is littered with tombstones that say “here lie the bones of yet another (primarily unsuccessful) challenge to free speech.”11

However, one cannot ignore the fact that much of this divisive rhetoric—which is frequently defended in the name of “Free Speech!”—either emerged in its current form, or intensified in volume (spatially and audibly) during Donald J. Trump’s presidential campaign in 2016, a trend that showed no signs of abating (quite the opposite, in fact) once Trump became the 45th President of the United States. Eschewing press conferences in favor of 140-character Twitter missives,12 and engaging in actions that suggest an insatiable desire for widespread public dissemination (although not necessarily approval) of his actions, Trump has taken the “rhetorical presidency” to a whole new level.13 This level has, most prominently, featured a constant clarion call condemnation of “fake news.” Admittedly, Trump is not the first politician (American or otherwise) to rail against news reports by decrying their accuracy. However, his accusations of “fake news” play an unprecedented role in his presidential rhetoric. Polls conducted at the end of Trump’s first year in office showed a disturbing increase in the percentage of Americans distrustful of the media.14 And those accusations are issued in a hyper-partisan manner.15 Therefore, in many ways Trump’s exhibitions of expressive intolerance are no different from those of the aforementioned college campus administrators and trigger-warnings-implementing educators. After all, one rarely finds the President seeking to suppress (via Twitter or other media mechanisms) conservative news outlets. Conveniently, the “fake” news comes from the President’s opponents, such as “the failing @nytimes” (the President habitually refers to the New York Times this way in his tweets). As Lara Trump observed, when “Real News Update” was created by her father-in-law’s 2020 presidential reelection campaign, it was intended to be an online news program which would “bring you”—“you [who] are tired of all the fake news out there…nothing but the facts.” What would these “facts” be? They would be “about all the accomplishments the president had this week,” accomplishments which had not received the coverage they were entitled to “because there’s so much fake news out there.”16

←4 | 5→Although one can point to these incidents as examples of societal intolerance, we must remember that they are also examples of free speech in action. For example, when the former San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick took a knee during the playing of the national anthem to protest the state of race relations in America, he was just as much exercising his expressive freedom as was Vice President Mike Pence when he decided to walk out of an NFL game in condemnation of the players who had chosen to follow Kaepernick’s lead.17 And when Heather Heyer gathered with counterprotesters in Charlottesville, Virginia, on that fateful day in August, 2017, she was in one sense exercising the very same freedom as the “Unite the Right” white nationalists to whom she stood vehemently opposed.

It is just as important to remember, though, that words can have powerful consequences that are oftentimes non-expressive. Words sometimes speak louder than actions, and words sometimes beget actions that ultimately drown out those words. Kaepernick’s efforts to draw attention to racial inequality have made him a prominent national spokesman on the subject, but at what cost? In response to his expressive actions the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) awarded him its 2017 Eason Monroe Courageous Advocate Award and in 2018 Nike made him the face of its “Just Do It” campaign.18 However, he has not played in the NFL since 2016, and his unemployment is widely perceived to be the result of the controversy surrounding his anthem protest. Tragically, for Heather Heyer the price that she paid for exercising her expressive freedom was far greater; when an individual drove his car, at high speed, into a crowd of the counterprotesters, he killed Heather and wounded dozens more.19 Thus, the situation is complicated by the fact that there is no clear line between what constitutes speech and what constitutes conduct.20 If we stand on the street corner and wave United States flags as the Labor Day parade goes by, is that speech or conduct? The answer is probably a higgledy-piggledy mess of “speech,” “conduct,” and “it depends.”

How do we make sense of all of these controversies? This brings us to our second argument. The irony is that while “Free Speech!” is increasingly in the news, and bandied about as something of value, that value remains under-theorized and, perhaps as an unintended consequence, is under threat; it is in danger of existing exclusively as a political slogan without substance. At best, it has become a rhetorical flourish in the spirit of political arguments, but at its worst it is a disingenuous mask for advancing extreme agendas and delegitimizing entire vocations, political factions, and positions about which reasonable people can (and do) disagree. If we agree that free speech is worth protecting, the next logical step is to examine its value to society. Some proponents may view expression as intrinsically valuable; this non-consequentialist ←5 | 6→conception of free expression tends to view speech as an end in and of itself rather than a particular avenue for achieving other social values. On the other hand, proponents may argue that free expression is valuable for its effects. The role of free expression in realizing other social values is also known as a consequentialist defense.21 All of the contributors to this volume share the goal of more carefully examining how and when free expression is valuable to civic society, and they also explore what we believe is a less discussed issue: how and when free expression is complementary to or in conflict with other social values. Whether one agrees with the idea of free speech being valuable for its consequences and effects or not, anyone who believes speech has social value should take responsibility in explaining how that value can or should be balanced against competing values, or integrated so as to achieve a wider range of social commitments. This is not merely the province of courts, which make difficult decisions on this front on a case-by-case basis.

Two circumstances—a failure to engage with foundational assumptions about the value of free expression, and uncritical, partisan sloganeering drawing on the exalted status of free expression in the pantheon of fundamental rights—have contributed to an impoverished civic discourse that obscures more than it illuminates. We instinctively know that driving a car into a crowd of protesters because one disagrees with their views is not something that can legitimately be welcomed under the umbrella of “free speech.” Similarly, although the hijackers of American Airlines flights 11 and 77, and United Airlines flights 175 and 93 probably operated under some belief that their actions were expressions of their opposition to American values, there is nothing controversial about saying that these “expressions” were not protected “free speech.” The harm associated with the terrorists flying those planes into buildings on September 11, 2001, is categorically different from, and far greater than that which is associated with, for example, glimpsing someone walking through a courthouse wearing a jacket emblazoned with the words “Fuck the Draft.”22 Consequently, there is a far greater, and far more legitimate governmental interest in preventing the “expressive” actions of the terrorists than there is in clamping down on profane sartorial choices. And the law recognizes these differing governmental interests.23 However, for every easy case there are hundreds of far harder ones. Is the creation of a wedding cake by a Christian baker a form of individual, artistic expression? Must that value supersede all others, such as an equality commitment that businesses serving the public avoid discriminating against same-sex couples? Look no farther than oral arguments in Masterpiece Cakeshop, Ltd. v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission for examples of U.S. Supreme Court justices struggling with this exercise in line-drawing.24

←6 | 7→The goal of this volume is to try and make sense of contemporary free speech controversies by engaging in critical analysis of them using theories of expressive freedom. One could simply say that the expressive actions and words of Colin Kaepernick, Heather Heyer, President Trump, and Professor George Ciccariello-Maher were examples of a “preferred” freedom being exercised. However, in terms of understanding their actions and words, that empirical statement does not get us very far, and certainly does not help us to understand why their actions and words should (or, perhaps, should not) be tolerated. Rather, if we use expressive freedom theories to engage in the normative inquiry that asks why, we are able to reach a far greater level of understanding of these contributions to the current societal dialogue. Indeed, if we do not, the dialogue ultimately looks more like a monologue.

Taking Free Speech Theory Seriously

Of course, at first blush many readers might seek to situate the idea of engaging in discussions using specific free speech theories and the works of philosophers somewhere along a continuum that runs from daunting, through frightening, to damn nigh impossible. The authors of the chapters in this volume are united in a belief that free speech theories do not have to be scary. We all encourage you, the reader, to “open your door” to theories, and not to view them as “enemies.”25 After all, whether you (the reader) know it or not, you have almost certainly already encountered many of the theoretical concepts that the contributors will discuss. Does a “marketplace of ideas” sound familiar? Or perhaps the “harm principle”?

Indeed, college students—who have sometimes been characterized as “snowflakes” seeking “safe spaces” from expression—appear to have found the proverbial treasure without a map, and may be in the vanguard in this “open door” effort. A recent New York Times article reported the results of a national survey of over 3,000 undergraduates who were directly asked about attitudes toward open and free debate and what is often framed as a competing, mutually exclusive concern for inclusivity and tolerance. The results of the survey are striking, and indicate students are actively wrestling with the normative questions we seek to expand upon in this volume. Among other findings, the survey found that “[c]ollege students believe about equally in free expression and pluralism, with nearly 90 percent saying that free expression protections are very or extremely important to democracy and more than 80 percent saying the same of promoting an inclusive and diverse society.” And while majorities across survey subgroups (except for men and Republicans) tended to rank the importance of the latter over the former in the abstract, ←7 | 8→the survey also found that “the vast majority of students say they would rather have a learning environment that is open and permits offensive speech to one that is positive but limits it.” This sentiment holds across all demographic and partisan subgroups of those surveyed. The survey and New York Times report also noted that majorities of students surveyed are willing to support restrictions on “hate speech” while also allowing for “free speech zones” to exist on campuses, and that students—contra some conventional accounts—do worry about the erosion of First Amendment protections.26 Looking beyond this survey, the advocacy of David Hogg, Emma González, Cameron Kasky, Kyle Kashuv, and other survivors of the February 14, 2018, mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, suggests that the next generation of undergraduates is not at all shy about exercising First Amendment rights (just ask Fox News personality Laura Ingraham).27 Taken together, these empirical findings strongly suggest to us that the “snowflake” claim is more slogan than substance, and that undergraduates are engaged in something more than recreational outrage.

In sum, there is good reason to believe that the spirit of philosophical inquiry is alive and well on college campuses, and is ripe for continued flourishing. We collectively view this volume as the next step in this robust philosophical debate. The chapters in this volume examine contemporary controversies concerning freedom of expression through a critical, theoretical lens. Each author walks the reader through the positions taken by commentators, ideologues, and partisans in recent controversies featuring cries of “Free Speech!” via assessments of competing justifications for freedom of expression. We use the reasons why polities value freedom of expression in the first place to engage in critical assessments and analytical explanations of contemporary controversies both in America and abroad. By the end of each chapter—and, for those brave souls, by the end of this volume—the reader will have a newfound appreciation of the underlying assumptions about human nature and the goals freedom of expression are meant to achieve.

Although this volume is a broad exercise in normative reasoning, we hope it is obvious that we do not seek to give primacy to any one theoretical justification for freedom of expression. It does not make an unqualified claim that free speech “absolutism”—freedom of expression must always trump all other fundamental commitments in any and all possible contexts—is the normative baseline against which all other positions are to be judged. Indeed, far too many of the current debates assume, without carefully examining, the value of freedom of expression, and assume there is only one value served by freedom of expression—a negative liberty on behalf of the individual—without sufficient attention to competing justifications that may be in substantial tension ←8 | 9→with one another. Freedom of expression is one important value among many, and its antecedent assumptions deserve more critical scrutiny and discussion than they currently receive in the modern political culture.

This survey of the theoretical landscape should not be interpreted as privileging some writers and thinkers over others. Far more has been written about normative philosophies of freedom of expression than we could ever hope to fit in a single introductory chapter (or perhaps single book). As such, the illustrative examples that follow were chosen because they represent “ideal types.” They are canonical—any survey of the free speech theoretical landscape would be noticeably barren without them. For readers interested in additional readings touching upon the theories surveyed, citations are provided in the endnotes to this chapter. Ultimately, while the contributors to this volume may or may not adopt these particular normative lenses, each chapter points to our general thesis: If “free speech” is to be more than a rhetorical flourish in political debate, substantive rather than blind authority, we must first attempt to answer the question of why free speech is valuable.

Beyond the First Amendment and the Supreme Court

Before perusing that theoretical landscape, however, it behooves us to say a few words about the explanatory paths not taken in this book. This is because speech theories are by no means the only way to understand expressive freedom controversies. When attempting to sort through such controversies, in the United States one might be inclined to consult the pages of the U.S. Reports for the First Amendment decisions and opinions of the U.S. Supreme Court, and accompanying commentary. There is no shortage of material to choose from. Many forests have fallen in the service of producing texts that describe and attempt to explain the evolution of freedom of expression doctrine generated by that Court.28 However, there are a number of problems associated with following the First Amendment path to the imposing bronze doors of the Court’s building on First Street NE in Washington, D.C.

Details

- Pages

- XIV, 256

- Publication Year

- 2020

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781433155963

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433155970

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781433155987

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433155956

- DOI

- 10.3726/b13431

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2020 (July)

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Oxford, Wien, 2020. XIV, 270 pp., 1 b/w ill.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG