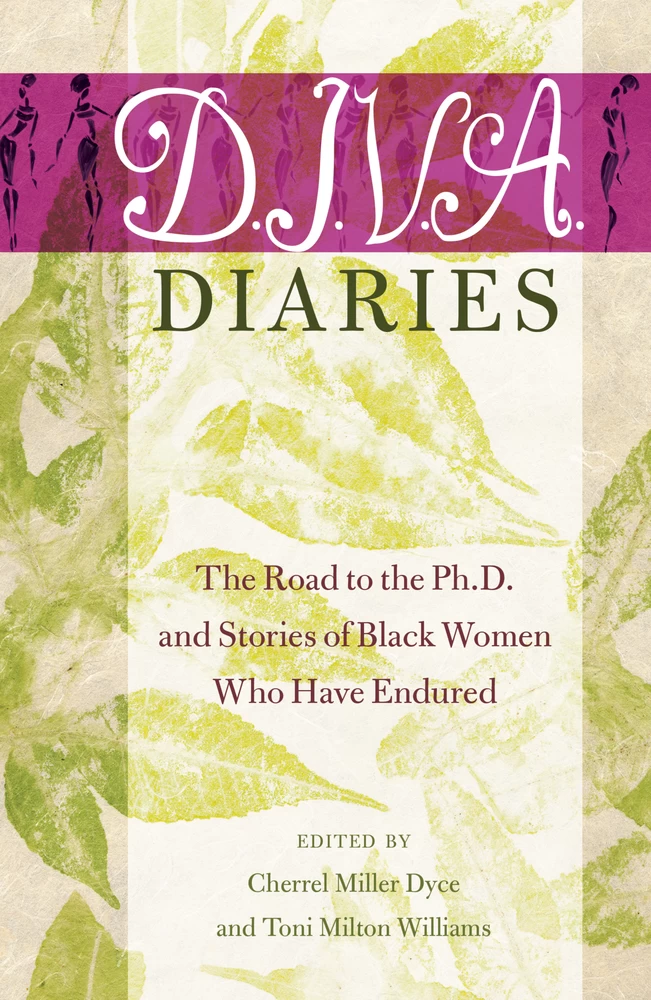

D.I.V.A. Diaries

The Road to the Ph.D. and Stories of Black Women Who Have Endured

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Inception of the Distinguished, Intellectual, Virtuous, Academic Sistas (DIVAS) Collective

- Meditations and Deliberations on DIVAS

- 1. Standing in the Gap as the Academic Intercessor

- 2. Putting on the Garment of Theory: Now You See Me, Now You Don’t

- 3. Collaboration and Encouragement as Mile Markers: Running for the Prize of PhD

- 4. Black Wonder Woman: Demystifying the “Supernatural” Powers of the Black Female Doctoral Student

- 5. Invisible Woman: A DIVA Seizing Visibility

- 6. Tales from a Hip-Hop DIVA: One Girl’s Journey from the Bronx to the PhD

- 7. Transition—“Changing the Game”: The Role of Qualitative Narratives in Research and Knowledge Construction

- 8. The Liberatory Educator: Transforming Lives, One Student at a Time

- 9. An African American Woman’s Continued Fight for a Pedagogical Education Inside of the Classroom

- 10. Present, but Not Present: The Personal and Educational Journey of a Doctoral Student Experiencing Deployment and Divorce

- 11. Through the Fire: Marked, but Not Burned—A Doctoral Journey Transformed by Life’s Obstructions

- References

- Contributors

- Series Index

We would first like to acknowledge the women in our families who have gone before us and paved the way. If not for your wisdom, persistence, support, passion, and love we would not be the women we are today.

We would like to thank all those who have supported DIVAS and our mission. Special thanks to Dr. Jean Rohr, for planting the seed for this narrative. ← ix | x →

← x | 1 →

The Courage

By Cherrel Miller Dyce

The beating of my heart reached a rhythm that produced an unsteady gait

My eyes became enlarged as I search the openness for your presence

Unconsciously we connect in shared silence with our pain as our thread

How could this be, this should have never happened, overflowing sorrow

Gather ourselves to a place in the spirit; gather ourselves to the plains of tomorrow

Victory is upon the horizon, the sun leading us onward to glory

Not now, not ever will we succumb

Never will we relinquish our grace, hopes, our joys, our heritage

Call yonder for our courage, as we press onwards for the sisters of tomorrow.

There is myriad research recently conducted about the success of Black women who are completing graduate programs. According to Holmes, Land, and Hinton-Hudson (2007), “the journey to higher education for many Black women has been long and arduous” (p. 106). The extant research literature is saturated with studies discussing doctoral student experiences. Studies have highlighted the role of social and cultural expectation (Golde, 2000), marginality (Gay, 2004), and identity development (Gardner, 2009). While African Americans only account for 14% of those enrolled in post-baccalaureate study, 65% of all doctoral degrees conferred to African Americans are earned by Black women (Aud et al., 2012). These studies are foundational because they intersect the current crises in doctoral education. According to the Council of Graduate Schools (2012): ← 1 | 2 →

Increasing demand for workers with advanced training at the graduate level, an inadequate domestic talent pool, and a small representation of women and minority graduates at all education levels are among some growing concerns over workforce issues that relate to the vitality and competitiveness of the U.S. economy. Improving completion rates for all doctoral students, and particularly for those from underrepresented groups, is vital to meeting our nation’s present and future workforce needs. (para. 1)

For Black women in academe, the issue of persistence and completion is compounded by factors such as race and racism (Patton, 2004), self-efficacy and marginality (Hinton, 2010), and socialization and gender (Ellis, 2001). From its inception, DIVAS (Distinguished, Intellectual, Virtuous, Academic Sistas) has allowed Black women doctoral students and new professionals to “stand in the gap” and become the “othermother” (Case, 1997; Foster, 1993; Guiffrida, 2005) as well as become fictive kin (Cook, 2010; Ebaugh & Curry 2000; Fordham, 1996) for Black women during their PhD process and into the academy.

In an early study of African American women scholars at predominately White institutions conducted by Moses (1989), among the problems typical of African American women faculty and administrators were lack of professional support and denial of access to power structures normally associated with their positions. Given these realities, DIVA Diaries presents the collective experiences of Black women doctoral students and emerging professionals as we navigated intersecting identities as not only Black women but also as wives, mothers, daughters, teachers, students, and novice researchers. DIVAS was formed in 2009 as a collective to address the unique concerns, hidden rules, and perspectives of Black female PhD students attending a public predominately White institution in the southeastern United States. After being told by DIVA Cherrel at our first meeting that “we are the Black face of education for tomorrow,” we immediately established a critical community and decided to continue meeting to support one another. According to Bettez (2011), fostering critical community among graduate students can help alleviate negative feelings and difficulties brought on by graduate studies. As institutions of higher education are grappling with the high percentage of students not completing the PhD, the DIVAS collective and our book DIVA Diaries provides stories from Black women of triumph through resilience, courage, community, and faith. We introduce the term “Black-centric critical consciousness” to name this collective experience. Furthermore, it provides awareness for Black women of their retention and needs while undertaking the PhD process. ← 2 | 3 →

A DIVACentric Epistemology: Conceptual Foundation

Othermothering

Conceptual foundations of DIVAS are twofold. The primary concept upon which DIVAS is built is othermothering. The practice of othermothering is a long-standing tradition in the African American community (Case, 1997; Guiffrida, 2005). Through othermothering, extended family and community members would come alongside a child to supplement the childrearing efforts of the biological mother (Guiffrida, 2005). When applied to the academy, othermothering becomes a means through which students are mentored, advised, challenged, and supported throughout their educational journey by others who have advanced standing in the institution. The DIVAS embrace this practice and incorporate it in to each of our activities. We are a sisterhood of Black women who value our shared history and understand the threads of ancestry that have othermothered, and now othersistered us. In highlighting our common African-centered lineage, Collins (1989) asserts that:

Moreover, as a result of colonialism, imperialism, slavery, apartheid, and other systems of racial domination, Blacks share a common experience of oppression. These similarities in material conditions have fostered shared Afrocentric values that permeate the family structure, religious institutions, culture, and community life of Blacks in varying parts of Africa, the Caribbean, South America, and North America. This Afrocentric consciousness permeates the shared history of people of African descent through the framework of a distinctive Afrocentric epistemology. (Collins, 1989, p. 755)

Details

- Pages

- VIII, 152

- Publication Year

- 2015

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433123856

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781453915219

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781454197799

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781454197805

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433123849

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-1-4539-1521-9

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2013 (June)

- Keywords

- DIVA Education race doctoral journey

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, Oxford, Wien, 2015. VIII, 152 pp., num. ill.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG