Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author(s)/editor(s)

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Section One: Introduction

- Chapter One: Facilitating School Renewal via the Learning-Centered Leadership Development Program: An Introduction

- Section Two: School Renewal in Nine Schools

- Chapter Two: Kindergarten Discovery Center’s School Renewal Activities

- Chapter Three: Urban School Finds Stronger Coherence and Better Understanding about Learning and Leadership via the Renewal Matrix

- Chapter Four: Use Data Notebook for School Renewal

- Chapter Five: School Renewal for Shared Leadership and Improved Student Results in a Persistently Low Achieving School

- Chapter Six: Implementing and Sustaining School Renewal Activities: Lessons Learned from Howard-Ellis Elementary School

- Chapter Seven: Sam Adams Elementary School Renewal Activities

- Chapter Eight: Two Closed Urban Schools = One New School: Using the Renewal Matrix Dimensions to Guide Success

- Chapter Nine: Zilwaukee School Culture Renewal: Implementation of The Leader in Me® Process

- Chapter Ten: Learning-Centered Digital Leadership

- Section Three: Summary and Reflection

- Chapter Eleven: Lessons from Eight Schools: Leadership Teams and Direction from a School Renewal Activities Matrix

- Chapter Twelve: Summaries and Reflections: Toward School Renewal

- Contributors

- Index

| vii →

We want to thank the publishers for permission to use the materials in the following sources:

Reeves, P., Palmer, L. B., McCrumb, D., & Shen, J. (2014). Sustaining a renewal model for school improvement. In Z. Sanzo (Ed.), From policy to practice: Sustaining innovations in school leadership preparation and development (pp. 267–292). Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publication.

Shen, J., & Cooley, V. E. (2012). Learning-centered leadership development program for practicing and aspiring principals. In K. L. Sanzo, S. Myran, & A. H. Nomoore (Eds.), Successful School Leadership Preparation and Development: Lessons Learned from US DoE School Leadership Program Grants (pp. 113–135). UK: Emerald Group Publishing.

| 1 →

| 3 →

Facilitating School Renewal VIA THE Learning-Centered Leadership Development Program

INTRODUCTION

How to improve our schools, particularly those high-needs schools, is a challenge for our nation. With the support from the US Department of Education’s School Leadership Program, Western Michigan University (WMU) and about a dozen high-needs public school districts in Michigan collaborated to conduct the Learning-Centered Leadership Development Program for Practicing and Aspiring Principals. Our effort on school improvement focuses on leadership, an underutilized approach to school improvement. We also emphasize both the content and process of the school improvement process. As far as content is concerned, we synthesize the literature and develop seven dimensions of school leadership that are associated with student achievement. The seven dimensions are (a) data-informed decision-making, (b) safe and orderly school operation, (c) high, cohesive, and culturally relevant expectations for all students, (d) distributive and empowering leadership, (e) coherent curricular programs, (f) real-time and embedded instructional assessment, and (g) commitment and passion for school renewal. In terms of process, we advocate the “renewal” model, rather than the “reform” model. In this chapter, we will introduce the seven dimensions for school renewal, the renewal model, and some details on how the Learning-Centered Leadership Development Program (LCLDP) is conducted. ← 3 | 4 →

LCLDP’S TWO KEY ELEMENTS: CONTENT AND PROCESS

LCLDP has a conceptual framework which consists of two key elements. The first key element is the content—the seven dimensions of school principalship that are empirically associated with improving student achievement. The second element is the process—the theory of learning and practice for adults in a complex organization. Learning activities range from knowing what is important and why (experiential), to what to do (declarative), to how to do it (procedural), to when to do it (contextual), and to what to look for as to results and how to make adjustments (evidential) (adapted from Waters, Marzano, & McNulty, 2003). From the process standpoint, principals, aspiring principals and school improvement team members are engaged in “renewal activities” aligned with the seven dimensions that will ultimately improve student achievement. Renewal activities are school-based improvement initiatives developed by principal, aspiring principals and teacher leaders to address an identified weakness or shortcoming related to the seven dimensions.

The first element of the conceptual framework for LCLDP: The Seven Dimensions as the Content

The program is based on current knowledge from research and effective practice. Principals, particularly those in high-need schools, face intensive pressure to raise student achievement. It has been increasingly argued that the main responsibility of school leadership is the improvement of teaching and student learning (Spillane, 2003).

Principals make a difference in student learning (e.g., Bossert, Dwyer, Rowan, & Lee, 1982; Goldring & Pasternak, 1994; Hallinger & Heck, 1996; Heck, Larson, & Marcoulides, 1990; Heck & Marcoulides, 1992; Knuth & Banks, 2006; Leithwood, Louis, Anderson, & Wahlstrom, 2004; Marcoulides & Heck, 1993; Marzano, Waters, & McNulty, 2005; Owings, Kaplan, & Nunnery, 2005; Waters & Kingston, 2005). However, the validity of the existing mechanisms for developing, certifying, and credentialing principals needs improvement. One shortcoming of the current paradigm of principal preparation is that the focus is more on general leadership characteristics and management functions than on leadership behaviors related to student achievement (Shen, et al., 2005). Based on the Balanced Leadership study (Marzano, Waters, & McNulty, 2005) and 30 additional high-quality studies (see Table 1 below), as well as our projects funded by the US Department of Education and The Wallace Foundation, we developed the Learning-Centered Leadership Development Program for Practicing and Aspiring Principals. We are using this intervention program to work with participants on seven dimensions of principal leadership. ← 4 | 5 →

Table 1.1. Principal Leadership Dimensions and Elements Empirically Associated with School Improvement and Student Achievement.

| Dimensions | Elements in Marzano’s Balanced Leadership | Elements in Other Research |

| A. Data-informed decision-making | • Monitors/evaluates | • The practice of teachers; student opportunity to learn; academic learning time (Hallinger & Heck 1996; Shen & Cooley, 2008; Shen et al., 2010) |

| • Situational awareness | • Supervising and evaluating the curriculum (Witziers, Bosker, & Kruger, 2003) | |

| • Information collection and analysis (Celio & Harvey, 2005; Leithwood & Jantzi, 1999; | ||

| • Organizational learning (Marks, Louis, & Printy, 2000; Schechter, 2008; Schechter & Feldman, 2010). | ||

| • Principals’ data-informed decision-making and its effect (Shen et al., 2010; Shen et al., 2012 a, b; Shen et al., 2015; Shen et al., in press) | ||

| B. Safe and orderly school operation | • Order | • Safe and orderly school environment; positive and supportive school climate; communication and interaction; interpersonal support (Cotton, 2003) |

| • Communication | • Governance (Heck, 1992; Heck & Marcoulides, 1993) | |

| • Discipline | • Planning; structure and organization (Leithwood & Jantzi, 1999) | |

| • Minimizing classroom disruptions (Sebring & Bryk, 2000) | ||

| C. High, cohesive, and culturally relevant expectations for all students | • Culture | • Goals focused on high levels of student learning; high expectations of students; community outreach (Cotton, 2003) |

| • Focus | • Climate (Heck, 1992; O’Donnell & White, 2005) | |

| • Outreach | • Leadership of parents positively associated with student achievement (Pounder, 1995) | |

| • Ideals/beliefs | • School mission, teacher expectation, school culture (Hallinger & Heck 1996) | |

| • Defining and communicating mission; achievement orientation (O’Donnell & White, 2005; Witziers, Bosker, & Kruger, 2003) | ||

| • Culture (Leithwood & Jantzi, 1999) ← 5 | 6 → | ||

| • Collective efficacy (Goddard, 2001; Goddard, Goddard, Kim, & Miller, 2011; Goddard, Hoy, & Hoy, 2004; Goddard & Salloum, 2011; Manthey, 2006; Moolenaar, Sleegers & Daly, 2012; Ware & Kitsantas, 2007) | ||

| • Collective responsibility (Lee & Smith, 1996; Wahlstrom & Louis, 2008) | ||

| • Culturally relevant pedagogy (Boykin & Cunningham, 2001; Dill & Boykin, 2000; Hurley, Alle & Boykin, 2009; Ladson-Billings, 1994, 1995a, 1995b, 1998) | ||

| D. Distributive and empowering leadership | • Input | • Shared leadership and staff empowerment; visibility and accessibility; teacher autonomy; support for risk taking; professional opportunities and resources (Cotton, 2003; Hallinger & Heck, 2010) |

| • Resources | • Cultivating teacher leadership for school improvement; shared instructional leadership (Marks & Printy, 2003) | |

| • Visibility | • Promoting school improvement and professional development (Witziers, Bosker, & Kruger, 2003) | |

| • Contingent reward | • Teacher empowerment (Louis & Marks, 1997) | |

| • Relationship | • Professional community (Louis, 2006; Louis, Marks, Kruse, 1996; Marks & Louis, 1997; Spillane, Halverson, & Diamond, 2001; Wahlstrom & Louis, 2008) | |

| • Social trust (Cosner, 2009; Sebring & Bryk, 2000) | ||

| E. Coherent curricular programs | • Curriculum, instruction, assessment | • Instructional organization (Hallinger & Heck, 1996; Heck, 1992; Heck & Marcoulides, 1993) |

| • Knowledge of curriculum, instruction, and assessment | • The integration of transformational and shared instructional leadership (Marks & Printy, 2003) | |

| • Supervising and evaluating the curriculum; coordinating and managing curriculum (Witziers, Bosker, & Kruger, 2003) | ||

| • Instructional program coherence (Newmann, Smith, Allensworth, & Bryk, 2001; Youngs, Holdgreve-Resendez & Qian, 2011) ← 6 | 7 → | ||

| F. Real-time and embedded instructional assessment | • Curriculum, instruction, assessment | • Instructional leadership; classroom observation and feedback to teachers (Cotton, 2003) |

| • Knowledge of curriculum, instruction, and assessment | • Instructional organization (Hallinger & Heck 1996; Heck, 1992; Heck & Marcoulides, 1993) | |

| • The integration of transformational and shared instructional leadership (Marks & Printy, 2003) | ||

| • Monitoring student progress (Witziers, Bosker, & Kruger, 2003) | ||

| • Instructional program coherence (Newmann, Smith, Allensworth, & Bryk, 2001) | ||

| G. Commitment and passion for school renewal | • Affirmation | • Self-efficacy (Smith, Guarino, Strom, & Adams, 2006), self-confidence, responsibility, and perseverance; rituals, ceremonies, and other symbolic actions (Cotton, 2003) |

| • Change agent | • Influence of principal leadership on school process such as school policies and norms, the practices of teachers, and school goals (Hallinger & Heck, 1996) | |

| • Optimizer | • The integration of transformational and shared instructional leadership (Marks & Printy, 2003) | |

| • Flexibility | • Visibility (Witziers, Bosker, & Kruger, 2003) | |

| • Intellectual stimulation | • Purposes and goals (Leithwood & Jantzi, 1999) | |

| • Encouraging teachers to take risks and try new teaching methods (Sebring & Bryk, 2000) |

Table 1.1 illustrates that the seven dimensions of the Learning-Centered Leadership Development Program represent current knowledge from research and best practices. The seven dimensions of principal leadership are based on two streams of literature. The first stream includes large-scale meta-analyses, such as those by Marzano, Waters, and McNulty (2005) and Cotton (2003). These meta-analyses consist of syntheses of the literature on the relationship between principal leadership and student achievement. However, the meta-analyses used original studies as data sources and, accordingly, there are additional requirements for studies to be included in the meta-analyses. In other words, meta-analyses have limitations in terms of what studies are included. For example, the meta-analysis by Marzano, Waters, and McNulty (2005) set criteria such as “The study involved K–12 students,” “effect sizes in correlation form were reported or could be computed” (p. 28). Thus, the second stream of our literature includes those recent, influential ← 7 | 8 → studies that were not included in the meta-analyses. We included research ideas such as

- • integration of transformational and shared instructional leadership (Marks & Printy, 2003; Hallinger & Heck, 2010),

- • collective efficacy (Goddard, 2001; Goddard, Goddard, Kim, & Miller, 2011; Goddard, Hoy, & Hoy, 2000; Goddard & Salloum, 2011; Manthey, 2006; Moolenaar, Sleegers & Daly, 2012; Ware & Kitsantas, 2007),

- • collective responsibility (Lee & Smith, 1996; Wahlstrom & Louis, 2008),

- • culturally relevant pedagogy (Boykin & Cunningham, 2001; Dill & Boykin, 2000; Ladson-Billings, 1994, 1995a, 1995b, 1998; Hurley, Alle & Boykin, 2009),

- • instructional program coherence (Newmann, Smith, Allensworth, & Bryk, 2001; Youngs, Holdgreve-Resendez & Qian, 2011),

- • professional community (Louis, Marks, & Kruse, 1996; Marks & Louis, 1997; Louis, 2006; Wahlstrom & Louis, 2008),

- • social trust (Sebring & Bryk, 2000; Cosner, 2009),

- • organizational learning (Marks, Louis, & Printy, 2000; Schechter, 2008; Schechter & Feldman, 2010), and

- • using data for decision-making (Celio & Harvey, 2005; Leithwood & Jantzi, 1999; Shen & Cooley, 2008; Shen et al., 2010; Shen et al., 2012; Shen et al., in press).

By utilizing the research findings from the empirical studies, LCLDP reflects comprehensive, up-to-date knowledge from research and effective practice.

The second key element of LCLDP: The five-levels-of-learning process to engage practicing and aspiring principals in school renewal in a complex system

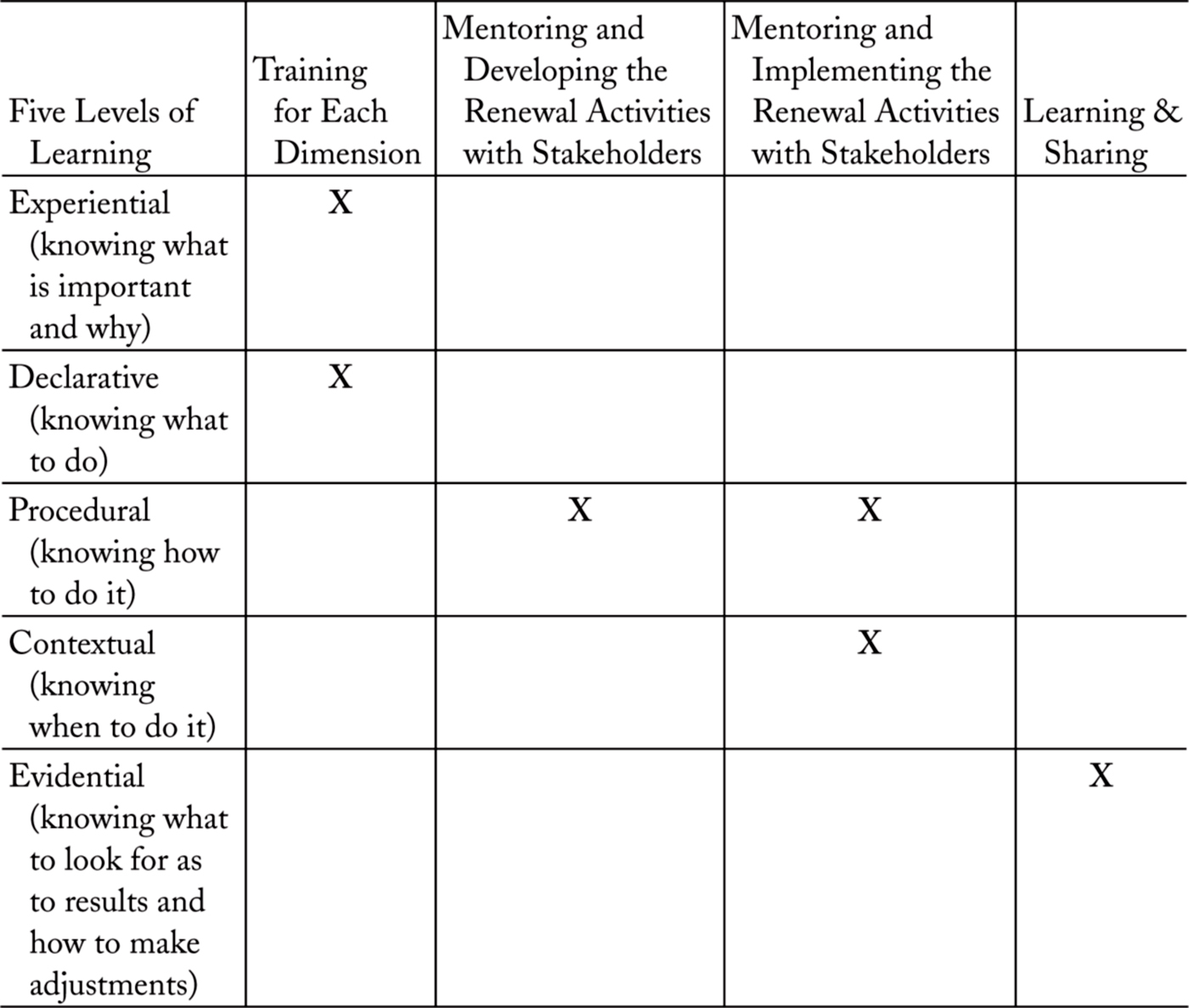

In the foregoing, we presented the seven dimensions as the content for LCLDP. In this section, we discuss the five-levels-of-learning process to conduct the learning activities, which is LCLDP’s second key element. The process focuses on “renewal,” rather than “reform”. The following table illustrates how we conduct the program.

There are four major groups of learning activities for participants. First, each participant participates in a workshop for each of the seven dimensions of principal leadership (each workshop is a distinct module focusing on one leadership dimension). The workshops utilize the theories of adult learning to emphasize job-embededness and reflection on participants’ practices (Darling-Hammond, 1998; Darling-Hammond & McLaughlin, 2011). Second, as an extension of each workshop, each pair of practicing and aspiring principals (from the same school), together with a mentor and the school’s stakeholders, examine and reflect upon ← 8 | 9 → current and desired practice of leadership dimensions in the school. Practicing and aspiring principals, together with teacher leaders in their school then develop a minimum of one renewal activity related to each dimension. For example, in relation to the dimension of data-informed decision-making, a pair of practicing and aspiring principals might begin or modify the use of data while observing teachers as part of the instructional supervision and evaluation process. Third, based on the development work in the previous point, the pair of practicing and aspiring principals implements, in partnership with the school’s stakeholders and the mentor, designs and implements at least one renewal activity for each of the seven dimensions. Finally, the participants and the LCLDP staff form a learning community to facilitate the sharing and reflecting upon their collective thinking and actions.

Table 1.2. Levels of Learning: A Seamless, Actions-oriented Approach (the Second Key Element of the Program).

As illustrated in Table 1.2 and the four learning activities discussed in the previous paragraph, the continuum of four major learning activities differs from the usual professional development practices. First, LCLDP activities focus on knowledge and skills at different levels, ranging from (a) experiential, to (b) declarative, (c) procedural, (d) contextual, and (e) evidential. Second, proposed activities are ← 9 | 10 → action-oriented and job embedded. With the support of a mentor, the school’s stakeholders and the LCLDP staff, each pair of practicing and aspiring principals plans and actually implements renewal activities in their school. Finally, LCLDP activities are results-oriented. Working with participants, LCLDP’s evaluation component investigates the outcome of renewal activities participants choose to implement.

Details

- Pages

- VI, 238

- Publication Year

- 2015

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433130922

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781453917107

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781454189442

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781454189459

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433130939

- DOI

- 10.3726/978-1-4539-1710-7

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2016 (February)

- Keywords

- K-12 School Digital Learning

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Frankfurt am Main, Oxford, Wien, 2015. XI, 238 pp., num. ill.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG