From Education to Incarceration

Dismantling the School-to-Prison Pipeline, Second Edition

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

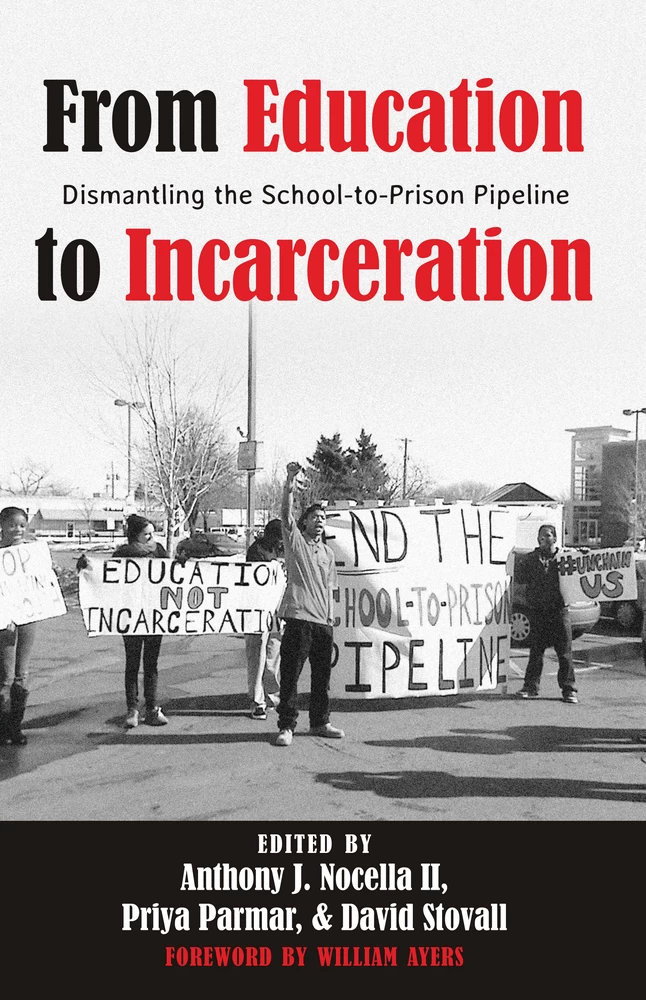

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author(s)/editor(s)

- About the book

- Advance Praise for From Education to Incarceration

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- Foreword (William Ayers)

- Preface (Frank Hernandez)

- References

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Every Day Is Like Skydiving Without a Parachute: A Revolution for Abolishing the School to Prison Pipeline (Anthony J. Nocella II / Priya Parmar / David Stovall)

- It Still Ain’t Good For Most Folks

- About the Book

- Summary of the Book

- Reference

- Part One: The Rise of an Imprisoning Youth Culture

- Chapter One: Criminalizing Education: Zero Tolerance Policies, Police in the Hallways, and the School to Prison Pipeline (Nancy A. Heitzeg)

- The School to Prison Pipeline Defined

- The School to Prison Pipeline: The Context

- Media Construction of Crime and Criminals

- The Rise of the Prison Industrial Complex

- The School to Prison Pipeline: Zero Tolerance and Policing in The Hallways

- Racial Disproportionality

- Increased Rates of Suspensions and Expulsions

- Elevated Drop-Out Rates

- Legal and constitutional Questions

- Interrupting the School to Prison Pipeline

- References

- Chapter Two: The Schoolhouse as Jailhouse (Annette Fuentes)

- Zero Tolerance, Zero Logic

- The Security State Goes to School

- A Different Approach

- References

- Chapter Three: Rethinking the School to Prison Pipeline (David Gabbard)

- From "School to Prison” to "School as Prison”

- References

- Chapter Four: Changing the Lens: Moving Away from the School to Prison Pipeline (Damien M. Sojoyner)

- Part 1—Black Los Angeles, Organizing, and Police Violence

- Part 2—Soft Hand Discipline

- Part 3—A New Model

- References

- Part Two: Targeting Youth

- Chapter Five: Punishment Creep and the Crisis of Youth in the Age of Disposability (Henry A. Giroux)

- The War Against Youth

- The Youth Crime-Control Complex

- Defending Youth and Democracy in the Twenty-First Century

- References

- Chapter Six: Targets for Arrest (Jesselyn McCurdy)

- When did Our Children Stop Being Sent Home with Homework and Start Being Sent to Jail in Handcuffs?

- J.D.B v. North Carolina

- Arresting Development

- Kindergarteners in Handcuffs

- Chaquita Doman (1998)

- St. Petersburg, Florida, Kindergartner (2005)

- Desre’e Watson (2007)

- Salecia Johnson (2012)

- Stories of Older Youth

- Student Arrested for Texting (2009)

- Tyell Morton: Senior Prank Gone Horribly Wrong (2011)

- Jacob Fleener: Principal Did Not See the Humor in a Facebook Parody (2011)

- Seventh-Grader Arrested for Burping in Class (2011)

- Consequences of Being a Target for Arrest

- The Data Do Not Lie, But They Do Confirm Our Fears

- Conclusion

- References

- Chapter Seven: Race and Access to Green Space (Carol Mendoza Fisher)

- Structural Racism

- Intersectionality of policies that support an eco-racist structural system

- General Demographics of San Antonio

- Environmental Risks and Regulatory Environment

- Water Quality Degradation

- Ozone

- Coal Burning Plants

- Rail Traffic

- Urban Compared to Suburban Pollution Sources

- Intersection of School to Prison and Eco-Racism

- Green Space

- Eco-racism and Green Space

- References

- Websites

- Part Three: Pushout Not Dropout of Marginalized Youth

- Chapter Eight: Red Road Lost: A Story Based on True Events (Four Arrows)

- References

- Chapter Nine: Emerging from Our Silos: Coalition Building for Black Girls (Maisha T. Winn / Stephanie S. Franklin)

- Why Collaboration? Why Now?

- Historical Educational and Legal Analysis—Silencing and Dismissing Black Girls

- Right to Education

- Zero Tolerance Policies: An Attempt to Destroy the Black Girl

- Where She Finds Her Power

- Who Am I? Black Girls' Stories of Triumph and Resilience

- You Don’t See Us But We See You

- Initiating a Dialogue that Focuses on the Needs of Black Girls

- References

- Chapter Ten: Messy, Butch, and Queer: LGBTQ Youth and the School to Prison Pipeline (Shannon D. Snapp / Jennifer M. Hoeing / Amanda Fields / Stephen T. Russell)

- Method

- Procedure and Participants

- Coding Analysis

- Results

- The "Problem” Youth Who Constitute the Pipeline Population

- Youth are Punished for PDA and Self-Expression

- Youth Who Protect Themselves are Punished

- Multiple Factors that Propel Push-Out

- Discussion and Conclusion

- References

- Part Four: Special Education Is Segregation

- Chapter Eleven: Warehousing, Imprisoning, and Labeling Youth “Minorities” (Nekima Levy-Pounds)

- Introduction

- The School to Prison Pipeline is Alive and Well in America

- Public Perception of Young Black Men as Criminals

- African American Males are in Need of Equitable Enforcement of Current Protections in Public Schools

- Conclusion

- References

- Chapter Twelve: Who Wants to Be Special? Pathologization and the Preparation of Bodies for Prison (Dean L. Adams / Erica R. Meiners)

- The School to Prison Pipeline

- New Frames and Old Stories of the Segregation of Students of Color

- Who Benefits? Assessing the Impact of Special Education Classification

- Building Power: Organizations Working for Change

- References

- Chapter Thirteen: The New Eugenics: Challenging Urban Education and Special Education and the Promise of Hip Hop Pedagogy (Anthony J. Nocella II / Kim Socha)

- Introduction

- Urban Education: The New Special Education

- Challenging White Supremacy

- Abolishing Special Education and Segregation

- Conclusion: Ending the New Eugenics and the Rise of Hip Hop Pedagogy

- References

- Part Five: Behind the Walls

- Chapter Fourteen: Prisons of Ignorance (Mumia Abu-Jamal)

- References

- Chapter Fifteen: At the End of the Pipeline: Can the Liberal Arts Liberate the Incarcerated? (Deborah Appleman / Zeke Caligiuri / Jon Vang)

- Introduction

- Locating Our Authorial Stances

- Education and Recidivism

- The State of Prison Education Programs

- What is a Liberal Arts Education?

- The Value of a Liberal Arts Education for the Incarcerated

- Reading and Writing in Prison

- Changing Personal Narratives

- Conclusion

- References

- Chapter Sixteen: Transforming Justice and Hip Hop Activism in Action (Anthony J. Nocella II)

- Culture of Violence

- Thinking About Alternatives

- What is Hip Hop?

- Transformative Justice

- Grassroots Activism

- References

- Part Six: Transformative Alternatives

- Chapter Seventeen: Back on the Block: Community Reentry and Reintegration of Formerly Incarcerated Youth (Don C. Sawyer III / Daniel White Hodge)

- Introduction

- Images of Black-Maleness in the American Psyche

- The Path to Prison: School to Prison Pipeline

- Real Lives, Real is Sues, and Reentry: Case Studies of Jason, Mike, and Larry

- Jason

- Mike

- Larry

- Reentry Problems

- Moving Forward

- References

- Chapter Eighteen: Youth in Transition and School Reentry: Process, Problems, and Preparation (Anne Burns Thomas)

- The Need for School Reentry Policy

- Transition from What to What? Defining the Process

- The Transition Process at School

- Working the Transition: Teachers and Court-Involved Youth

- Processing the Process: Concluding Thoughts

- References

- Chapter Nineteen: A Reason to Be Angry: A Mother, Her Sons, and the School to Prison Pipeline (Letitia Basford / Bridget Borer / Joe Lewis)

- Background on the Writers

- The School to Prison Pipeline

- Disproportionate, Exclusionary, and Repressive Discipline

- Zero Tolerance Policies

- Fostering Meaningful Relationships in Schools

- Toward Culturally Responsive Communities of Learning

- References

- Part Seven: Building Alternatives to Punitive Justice

- Chapter Twenty: Ending the School to Prison Pipeline/Building Abolition Futures (Erica R. Meiners)

- Departures

- The Carceral Nation and Why Abolition

- A State of the Field

- Tensions for Scholarship Within the Field

- Exceptionality, or the Difference Difference Makes

- The Shifting State

- Building Safe Communities and Schools

- Negotiating Intersectionality

- Collectivizing for Abolition Futures

- Acknowledgments

- References

- Chapter Twenty-One: A New Choice of Weapon: Activism Through Hip Hop and Restorative Justice (Arash Daneshzadeh)

- It Ain’t Hard to Tell : The Eugenics of Trafficking Eurocentric Lies

- What Goes Around: Implications for School Leadership and Organizational Behavior

- Represent: Hip Hop Activism as Case Studies

- If I Ruled the World: Restorative Justice and Space-Making in Hip Hop

- References

- Chapter Twenty-Two: Youth of Color Fight Back: Transforming Our Communities (Emilio Lacques-Zapien / Leslie Mendoza)

- Introduction to the Youth Justice Coalition, Los Angeles

- Educational Discrimination Against System-Involved Youth: Conditions of the School to Prison Pipeline

- Transformative Justice: Community-Based Models of Justice

- Youth Empowerment

- You Can’t Build Peace With a Piece

- National Statement by Youth of Color: On School Safety and Gun Violence in America

- Conclusion: Steps in Community Organizing

- “From Isolation to Action”

- Finding Our Voice

- References

- Part Eight: Tactics for Abolition

- Chapter Twenty-Three: Tactics and Strategies to Organize for Abolishing the School to Prison Pipeline (Anthony J. Nocella II)

- Problems of the STPP

- Solutions to the STPP

- Martin L . King Jr. Six Steps for Social Change

- Gandhi ’s Four Steps for Social Change

- Elements of Conflict

- Working to Be in Solidarity With Oppressed People

- Twenty-Step Process for Organizing a Public Education Forum

- Ground Rules

- Fighting Repression

- Tactics of Fighting Repression

- Basic Security Culture

- References

- Chapter Twenty-Four: Abolition Strategies for Teachers Fighting Academic Repression in the Corporate-Academic Industrial Complex (Priya Parmar)

- Philosophical Considerations

- Pedagogical Considerations

- References

- Chapter Twenty-Five: Seven Considerations for “School” Abolition (David Stovall)

- Afterword (Bernardine Dohrn)

- Appendix: Organizations and Resources

- California

- Colorado

- Connecticut

- Delaware

- District of Columbia

- Florida

- Georgia

- Illinois

- Louisiana

- Massachusetts

- Michigan

- Minnesota

- Mississippi

- Missouri

- New Jersey

- Nevada

- New York

- North carolina

- Ohio

- Oregon

- Pennsylvania

- Rhode Island

- South Carolina

- Texas

- Virginia

- Washington

- Wisconsin

- Child Defense—Cradle to Prison Pipeline Fact Sheet

- Campaign for Youth Justice—youth Justice Awareness Month: Guide to Passing a Resolution

- Aclu—Locating the School to Prison Pipeline

- Dignity in Schools: Investment in Education vs. Incarceration

- Dignity in Schools—what is School Pushout?

- Contributors

- Series index

We seem somehow destined to be confined for a time in a lockup-state-of-mind. Perhaps because we’ve lived so long in a culture of discipline and punish, or perhaps because the traditional American Puritanism became ravenous once again and demanded to be fed, or perhaps because our go-to-jail complex developed obsessive-compulsive hyper-activity—whatever the reasons, many Americans hardly noticed as we slipped down the proverbial slope that Angela Davis and Ruthie Gilmore, Erica Meiners and Bernardine Dohrn had predicted, and we woke up living in a full-blown prison nation. There’s no sense denying it: we are now marked indelibly as a carceral state (look it up), with mass incarceration the defining fact of life in the United States today (whether acknowledged or not) just as slavery was the fundamental reality in the 1800s (whether acknowledged or not).

And that fact points to the true and deep-seated reason underneath the phenomenon of mass incarceration: white supremacy dressed up in modern garb, structural racism pure and simple. The system has been dubbed “the new Jim Crow” by the brilliant lawyer and activist Michelle Alexander, who notes that there are now more Black men in prison or on probation or parole than there were living in bondage as chattel slaves in 1850; that there are significantly more people caught up in the system of incarceration and supervision in America today—more than six million folks—than inhabited Stalin’s Gulag at its height; that the American Gulag is the second largest city in this country, and that while the United ← xi | xii → States constitutes less than 5% of the world’s people, it holds more than 25% of the world’s combined prison population; that in the past twenty years the amount states have spent on prisons has risen six times the rate spent on higher education; and that on any given day tens of thousands of men, overwhelmingly Black and Latino men, are held in the torturous condition known as solitary confinement. You get the picture.

All of this indicates that we seem destined to be confined in that lockup-state-of-mind for the foreseeable future, or until we change the frame or flip the script, and—fed up—rise up.

That’s precisely the assignment courageously taken on by Anthony J. Nocella II, Priya Parmar, and David Stovall—they want to revolutionize the conversation. And with From Education to Incarceration: Dismantling the School to Prison Pipeline they’ve done just that, leaping into the whirlwind full force and constructing a powerful weapon for the forces of prison abolition, and an essential handbook for educators.

This book maps in devastating detail the treacherous path constructed by the powerful for the children of formerly enslaved human beings, recent immigrants, first-nation people, and the poor—a path that’s earned the colorful metaphoric phrase “the school to prison pipeline.” A pipeline runs in a single direction, and once entered into the mouth, destiny sweeps everything before it to the bottom; a pipeline offers no exits, no deviations or departures, no way out—unless it fractures. From Education to Incarceration is not focused on prison reform or tinkering with the mechanisms of the pipeline to make it “fairer” or more efficient; it’s aimed, rather, at ripping open the pipeline, upending the assumptions that got us where we are, and then throwing every section of pipe and all the braces and supports into the dustbin of history.

Schools for the poor—many urban and rural schools, and increasingly suburban schools as well—share striking similarities with prisons. In each site, discipline and security take precedence over knowledge or human development; in each site, people are subordinated to the will of—and forced to follow a strict routine set by—others, isolated from the larger community, and coerced to do work that they have no part in defining; in each folks are inspected, regulated, appraised, censured, ordered about, indoctrinated, sermonized, checked off, assessed, and kept under constant surveillance, at every turn to be noted, registered, counted, priced, admonished, prevented, reformed, redressed, and corrected. And on top of all this, students and prisoners alike are most often described by their minders through their aggregate statistical profiles: race and ethnicity, occupation or family income, residence, and religion. Schools for the poor are the prep schools for the prisoners of tomorrow.

But in spite of the increasing use of disciplinary techniques in schools, the prison analogy breaks down in one significant way: teachers are not prison guards, and our highest aspiration is not summed up in a single word: control. ← xii | xiii → Teachers are positioned as both subjects and objects of school surveillance, and uniquely, then, situated to help students develop a critical awareness of, and perhaps even some potential lines of resistance to, the technology of power in today’s maximum-security schools. Teachers can take the prison and the analogy, the pipeline and the metaphor, as objects of study.

In schools shot through with mechanisms of disciplinary surveillance, the technology of power itself can constitute part of a humanizing curriculum. Students can think critically about disciplinary power, about how they are being watched, by whom, and for what purpose. They can question, and they can act. By questioning and acting ourselves, teachers can show them how it’s done.

I come from a large Latino family. Including myself, there are six siblings. In all, I have twenty-three nieces and nephews and forty great-nieces and great-nephews. Some of them are just entering school; others have graduated from high school and are now attending institutions of higher education. Several have completed their baccalaureate degree and are entering graduate programs. One great-niece in particular has had her challenges as a student in a school where police officers are present every day. And as a result of a scuffle with another student, my great-niece was handcuffed, given a citation, and placed on file at the local juvenile criminal justice center. The citation, if not paid soon after issuance, will increase over time, and must be paid in full before my great-niece can submit a driver’s license application for consideration.

Recently, this same great-niece decided to skip school for a day. As a result of her decision, the administration, in collaboration with the juvenile system, equipped her with an ankle monitor to track her every move, particularly during school days. This past year, my great-niece completed the eighth grade and cele-brated her 14th birthday—and she is on what some call the “school to prison pipeline.” Unfortunately, the case of my great-niece is not unusual; it is all too common.

Across the United States, police habitually arrest youths and transport them to juvenile detention centers and, depending on the age of the youth, sometimes to the city or county jail. More often than not, these individuals are arrested for ← xv | xvi → minor disruptions. The arrests do not take place in the early weekend morning hours nor do they take place in questionable neighborhoods. Rather, these arrests occur in PK–12 schools, a place where students should feel protected; a place that is often referred to as the “equal playing field”; a place that is often identified as the “gateway” to higher education. Unfortunately for some students, there is a significant divide between what schools should be and what schools are.

Surges in arrests among youths similar in age to my great-niece have occurred for such infractions as scuffles, truancy, cussing, and disobeying directions. And in no other state have these school-based arrests been more prevalent than in Texas, the state where I work as dean of education for a small master’s degree-granting institution. According to the New York Times, (Eckholm, 2013) police officers based in Texas schools write more than 100,000 citations each year for students. And most often, the students receiving the citations lack access to legal counsel, amass huge fines, are required to do community service, or receive a criminal record that may weaken their prospects for future employment or service to country. De’Angelo Rollins, a 12-year-old middle school student, became a statistic in Texas’s growing number of incidents between school-based police officers and students. After he and another boy scuffled, both were given citations. Specifically, Rollins pleaded no contest, paid a fine, was sentenced to twenty hours of community service, and was placed on four months of probation. Our school system is now looking a lot like our criminal justice system. And the students arrested are getting younger.

Take, for example, Salecia Johnson. According to CNN Newswire, (Campbell, 2012) when officers arrived at Creekside Elementary in Milledgeville, Georgia, Salecia was on the floor of the principal’s office screaming and crying. After numerous attempts to calm Salecia down, she pulled away from the officers and resisted them when they tried to pick her up. According to the police report, Salecia was eventually handcuffed and brought to a police station.

This school to prison pipeline has been funneling more and more students over the years. The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) has identified several onerous factors that help clear this path to incarceration. The first factor is students’ attendance at under-performing schools. Low-performing schools are usually located in impoverished communities and have high gaps in achievement when compared with other schools. These low-performing schools tend to have substandard facilities, lack up-to-date books, have high faculty turnover, and more often than not, hire unlicensed or unqualified teachers. It is not unusual for teachers to have low expectations of students, which can contribute to students’ decisions to skip school or even drop out entirely.

The second factor underlying the school to prison pipeline is the rather abstract world of zero tolerance discipline policies, which are in place at many schools and which have very concrete, real-world effects. These policies leave ← xvi | xvii → little room for questions or for consideration of complex circumstances, and usually result in expulsion or suspension from school; that is, zero tolerance is applied across the board for a variety of infractions and circumstances. As a result, students are more likely to get pushed through the pipeline and into the juvenile justice system than would be the case if the students were exposed to tailored, thoughtful interventions.

The third factor is students’ attendance at schools where police staff the hallways and deal with schoolwide discipline. Rather than rely on teachers and administrators to handle school-discipline issues, school districts are enlisting full-time police officers. This means that students are more likely to be arrested for nonviolent behaviors than in the past. The fourth factor is alternative schools where some students enroll after having been expelled or suspended from traditional schools and where the students can expect to receive a sub-par education derived from remedial curriculum. The combination of these factors can have the effect of increasing the likelihood that troubled students will wind up in a local juvenile detention facility.

This school to prison pipeline needs to be cut off and dismantled. That’s exactly what this volume proposes in detail. It reviews and clarifies works by scholars and practitioners who are exploring ways to confront and overcome this dangerous mindset privileging incarceration over education. The volume is divided into five parts whose topics range from the culture of youth incarceration to recommended alternatives to youth incarceration. The writings in this volume uncover important yet subtle relationships between the targeting of youth, incarceration rates, the segregating of youth, and the need for transformation. The volume pushes us to understand not only the devastation of imprisoning our youth but also solutions to the problem.

REFERENCES

Campbell, A., (April 17, 2012). 6-year-old student handcuffed, arrested by police in Georgia. http://www.12newsnow.com/story/17516292/6-year-old0student-handcuffed-arrested-by-police-in-georgia.

Eckholm, E., (April 12, 2013). With police in schools, more children in court. New York Times http://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/12/education/with-police-in-schools-more-children-in-court-.html.

Anthony, Priya, and David would like to give love to our family and friends, who have supported us, challenged us, and laughed with us over the many years on this planet. We would also like to thank everyone at Peter Lang especially Phyllis Korper, Stephen Mazur, Inda Muntu, Chris Myers, Bernadette Shade, Sophie Appel, and the series editor Shirley Steinberg, a wonderful scholar and human being. We would also like to thank the brilliant and powerful contributors to this book, who allowed us to make a radical and critical tool to aid in the dismantling of the school to prison pipeline, prison industrial complex, and the academic industrial complex. We would like to give great appreciation to Bill Ayers for writing the Foreword, Frank Hernandez for writing the Preface, and Bernardine Dohrn for writing the Afterword. We would like to thank Jason Del Gandio, Peter McLaren, Barbara Madeloni, Heidi Boghosian, Mechthild Nagel, Jamie Utt, Joy James, Emery Petchauer, Paul C. Gorski, Ruth Kinna, César A. Rossatto, David Gabbard, Paul R. Carr, John Lupinacci, E. Wayne Ross, Steve Fletcher, and Joanna Lowry for reviewing this book on such a short deadline. Finally, we would like to thank each other, the editors, for the collaboration, creativity, the long talks, many e-mails, and struggle to make this important book come to life! We hope From Education to Incarceration will create consciousness and inspire youth, teachers, professors, community organizers, politicians, and activists to take action against high-stakes tests, standardization, cultural imperialism, normalcy, push-outs, special education, segregated education, youth detentions, police brutality, and continued police presence in schools.

Patience has its limits. Take it too far, and it’s cowardice.

—GEORGE JACKSON

To Hell with Good Intentions

—IVAN ILICH

IT STILL AIN’T GOOD FOR MOST FOLKS …

July 13, 2013: A jury of six (predominantly white) women found George Zimmerman, whose mother is Hispanic and whose father is white, not guilty of manslaughter or second-degree murder in the death of Trayvon Martin, an unarmed African-American male walking home in a gated complex in Florida after purchasing a drink and some candy. Despite the fact that Trayvon was an unarmed minor with no criminal record, a jury of Zimmerman’s supposed peers concluded that Zimmerman believed his life was being threatened and was justified in shooting Trayvon through the chest. Even though law enforcement had told Zimmerman to wait in his car and not to pursue Trayvon, the jury felt that Zimmerman was justified in his pursuit of the teen. Per a law deeply rooted in Florida’s “stand your ground” legislation, armed persons are allowed to use deadly force if they feel their life is in danger. ← 1 | 2 →

August 9, 2014: Ferguson, Missouri, 18-year-old Michael Brown was fatally shot by 28-year-old police officer, Darren Wilson. Wilson claimed he feared for his life as Brown approached him. As a result, Wilson shot the unarmed Brown twelve times. A Grand Jury failed to indict.

July 14, 2014: Staten Island, New York, 43-year-old Eric Garner died as a result of an illegal chokehold performed by 29-year-old NYPD officer, Daniel Pantaleo. Once Garner was brought to the ground, Pantaleo released his chokehold, but kept Garner’s face pressed to the concrete as four other officers attempted to restrain him. As Garner was lying face down on the sidewalk, pleading with them by repeatedly (twelve times) stating “I can’t breathe,” officers refused to release pressure until Garner lost consciousness. Paramedics arrived seven minutes later but failed to administer CPR. Approximately one hour later, Garner was officially pronounced dead at the local hospital. The Medical Examiner ruled Garner’s death a homicide as a result of the chokehold by Pantaleo. A Grand Jury failed to indict.

Details

- Pages

- XXII, 450

- Publication Year

- 2018

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433135170

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781433145100

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433145117

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781433145124

- DOI

- 10.3726/b11313

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2018 (October)

- Keywords

- juvenile justice youth national concern

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Oxford, Wien, 2018. XXII, 450 pp., 18 b/w ill., 15 tables

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG