Black Magic Woman

Gender and the Occult in Weimar Germany

Summary

The book investigates the significance of the occult in the Weimar period by drawing on popular, scientific, and legal writings of women’s involvement in the occult. In addition to examining reports of women engaging in actual occult practices (expressive dance, mediumism, and witchcraft), this book also considers various fictional depictions of women as demonic or as possessing supernatural powers (ghosts, vampires, and monsters). The author contends that both actual practices, as well as fictional depictions, constructed an imaginary female identity as a dangerous and grotesque monster.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: The Occult Woman as Metaphor for Weimar’s New Woman

- Chapter 1: The Ghost

- Chapter 2: The Vampire and the Monster Double

- Chapter 3: The Witch and the Gypsy

- Chapter 4: The Trance-Dancer and Medium

- Works Cited

- Index

- Series Index

Figures

←vii | viii→Figure 12. Vampyr. Scene from Vampyr. Producer Carl Theodor Dreyer; director Dreyer, 1932.

←viii | ix→Figure 14. Max Schreck in Nosferatu. Producer Albin Grau; director F. W. Murnau, 1921.

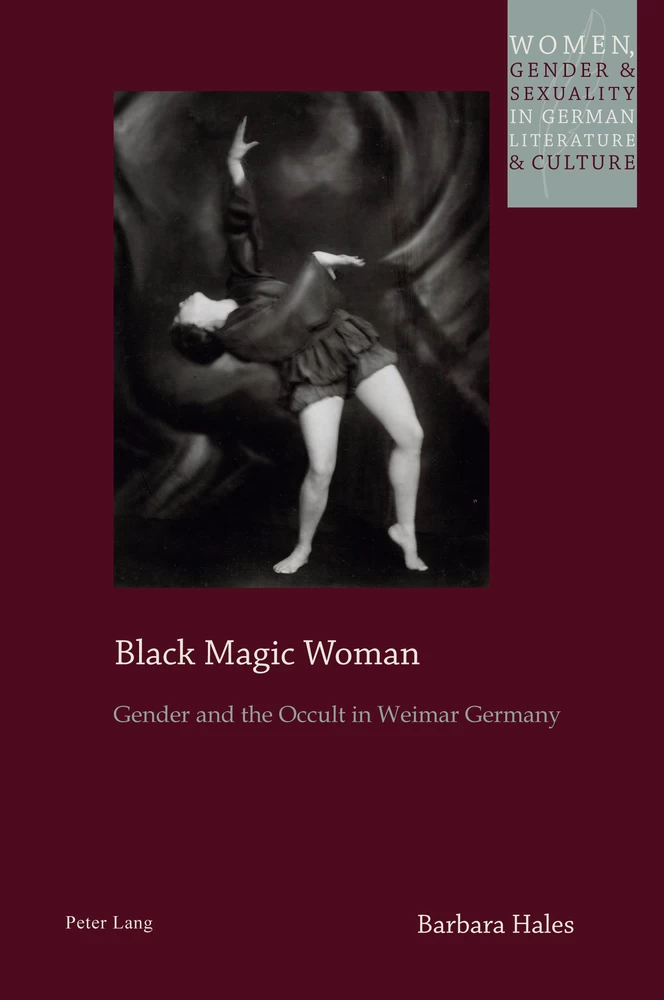

Figure 15. Mary Wigman performing Hexentanz (Witch Dance, 1926). Photo by Hugo Erfurth.

Figure 16. Mary Wigman performing Hexentanz II (Witch Dance II, 1926).

Figure 18. Pola Negri and Harry Liedtke in Carmen. Producer Paul Davidson; director Lubitsch, 1918.

Figure 19. Pola Negri in Sumurun. Producer Paul Davidson; director Lubitsch, 1920.

Figure 21. Brigitte Helm in Metropolis. Producer Erich Pommer; director Lang, 1927.

←ix | x→Figure 24. Totenmal (Call of the Dead, Wigman, 1930). Unknown photographer.

Figure 25. Schicksalslied (Song of Fate, Wigman, 1935). Photo by Charlotte Rudolph.

Acknowledgments

This project is the culmination of many years of research spurred on by lively discussions with colleagues. I am especially grateful to those scholars with whom I have had the pleasure of working, including Mila Ganeva, Sara Hall, Anjeana Hans, Barbara Kosta, Barbara Mennel, Ingeborg Majer O’Sickey, Mihaela Petrescu, Christian Rogowski, Philipp Stiasny, Regine Wagenblast, and Cynthia Walk. Irene Guenther’s generous contribution of her father Peter Guenther’s library on expressive dance (Ausdruckstanz) was essential in realizing my vision. I moreover thank my coeditor, and friend, Valerie Weinstein for her feedback and support. Her close reading and regular comments on the manuscript helped to refine my writing and enrich my thesis. I am also thankful to the anonymous peer reviewers and editors at Peter Lang for their valuable feedback. My thanks in particular go to Laurel Plapp for shepherding the book through all phases of publication. Additionally, I would like to thank my home institution, University of Houston Clear-Lake, for Faculty Development leave to work on the project, as well as financially supporting its production.

Some of the material used in the book first appeared in “Dancer in the Dark: Hypnosis, Trance-Dancing, and Weimar’s Fear of the New Woman” Monatshefte 102.4 (Winter 2010): 534–49.1 Aspects of the work herewith likewise made their first appearance in “Mediating Worlds: The Occult as Projection of the New Woman in Weimar Culture” German Quarterly 83.3 (Summer 2010): 317–32.

I would further like to recognize Louise Chapman for the editing help and indexing. She did an amazing job with the manuscript in preparation for publication. I would also like to thank my graduate students, James Dillard and Christen Symmons, for assistance with the images. For minting in me a love of learning, I thank my mother: Marjorie Hales.

←xi | xii→Finally, I am grateful to my wonderful husband and colleague, Daniel Silvermintz, who has patiently read and commented upon several versions of the entire manuscript. Without question, his enthusiasm about the project has not only improved the manuscript in countless ways: he has helped to bring it to fruition.

1 © 2010 by the Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System. Reprinted by courtesy of the University of Wisconsin Press.

INTRODUCTION

The Occult Woman as Metaphor for Weimar’s New Woman

If you are a woman and dare to look within yourself, you are a Witch. You make your own rules. You are free and beautiful. You can be invisible or evident in how you choose to make your witch-self known. You can form your own Coven of sister Witches (thirteen is a cozy number for a group) and do your own actions. […] You are a Witch by saying aloud, “I am a Witch” three times, and thinking about that. You are a Witch by being female, untamed, angry, joyous, and immortal.

Details

- Pages

- XII, 206

- Publication Year

- 2021

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781789976816

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781789976823

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781789976830

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781789976847

- DOI

- 10.3726/b17711

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2021 (March)

- Keywords

- Gender Occult Weimar Germany Barbara Hales Black Magic Woman

- Published

- Oxford, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, New York, Wien, 2021. XII, 206 pp., 5 fig. col., 20 fig. b/w.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG