The Antiglobalist

A Central European Leftist Perspective

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

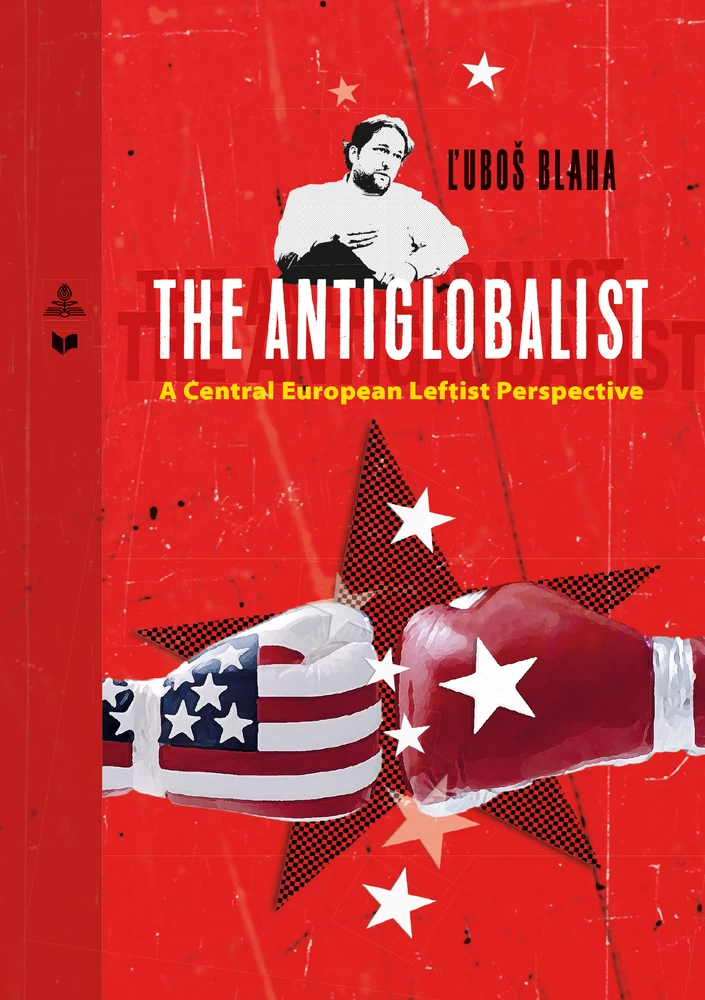

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgement

- 1. Introduction: A spectre of antiglobalism

- 1.1 Globalization and resistance movement

- 1.2 Perspective of the Central European Left

- 1.3 Marx is back!

- 1.4 New problems, new Marxism

- 2. The problem is global capitalism

- 2.1 It’s class, stupid!

- 2.2 Neoliberalization as an artificial product

- 2.3 Globalization or Americanization?

- 2.4 So far from God, so close to transnational corporations

- 2.5 Crisis of capitalism and the roots of inequality

- 2.6 Escape from responsibility

- 2.7 Individualism, racism and militarism

- 3. Deglobalize or perish

- 3.1 Anti-globalists v. alter-globalists

- 3.2 Cosmopolitanism as a dead end

- 3.3 What is wrong with the cultural Left?

- 3.4 Neo-fascism is the child of global capitalism

- 3.5 Back to Bretton Woods?

- 3.6 Deglobalization as a leftist alternative to global capitalism

- 3.7 Classical Left and its socialist projects

- 4. Conclusion: Socialism, not liberalism

- 4.1 The limits of universalism: Neither chauvinism nor parochialism

- 4.2 The trap of the postmodern Left

- 4.3 Socialism or barbarism – it’s already here again!

- Literature

I would like to thank especially my family: my wife Zuzana and my children Adam and Lilliana for the immense patience they had with me during the preparation (not only) of this book. They are my greatest supporters together with my mother Jana, my father Milan and my sister Nataša, whom I also thank for everything.

Many of my friends influenced and inspired me, among whom I would like to highlight the late Branislav Polách, who was my exemplar and mentor in many respects and guided my life philosophy the most, together with my closest family.

I appreciate all the advice from colleagues in the field of science and politics; in the dispute over globalization and the character of the modern Left, Jan Keller, Ilona Švihlíková, Oskar Krejčí, Josef Skála, Karel Klimša, Miro Číž and Míla Ransdorf (honour his memory) have been a great support to me recently. For a long assistance, I thank also Miroslav Pekník, Ladislav Hohoš, Jozef Lysý, Peter Dinuš, Martin Muránsky and Peter Daubner.

I especially appreciate the support of those, who have contributed financially to the translation of this book, thanks to which The Antiglobalist is published in English. My thanks go to Jan Keller, Viliam Jasaň, Institute of A.S.A. (in particular Vlado Faič), trade union KOVO (especially to Emil Machyna), Dušan Muňko, Vladimír Baláž and other people who, although they do not necessarily share my Marxist views on social development, they have contributed to the publication of a book that offers an alternative world view and which can be provocative and radical in the Slovak society. I respect people with open mind and courage to go against a tide.

The need for a constantly expanding market for its product chases the bourgeoisie over the entire surface of the globe. It must nestle everywhere, settle everywhere, establish connections everywhere. The bourgeoisie has through its exploitation of the world market given a cosmopolitan character to production and consumption of every country.

Karl Marx

Under the word “antiglobalist,” many people will imagine a furious nationalist, who rejects not only international solidarity, and the existence of cross-border or global problems, but who surely finds even high-speed internet and trans-oceanic flights disgusting. In short, a complete dimwit. Others will imagine a violent anarchist with a hood on his head, leading an enraged crowd and throwing Molotov cocktails at cops. Not just dimwits, but also hooligans!

The mainstream media depict antiglobalists as sheer evil, as idiots, extremists, criminals and fanatics. Yet, everything is different. The position I am going to present and advocate in this book is to some extent antiglobalist, but it is not nationalistic, and not in the least violent. On the contrary, it is internationalist, radically left-wing and peaceful.

My approach is engaged. I base my theory primarily on leftist inspirations, and I do not hide this fact in any way. Many of my considerations are inspired by Karl Marx and by modern Marxism, or neo-Marxism. However, alongside Marxism, I utilize other left-wing political concepts, from social liberalism to anarchism. My other inspirations include communitarianism and realism in the field of international politics. The political values that I am trying to defend have their source in left-wing anti-capitalism, and I state this without fear that my value profile might weaken the strength of my arguments. Like Immanuel Wallerstein, I am convinced that the only possible way to objectivity is an open-minded and engaged approach of social scientists who mutually dispute. It is a prerequisite to play a fair game and not to pretend that there is something like valueless social sciences. Wallerstein described it exactly: “Every choice of conceptual framework is a political option. Every assertion of ‘truth’, even if one qualifies it as transitory truth, or heuristic theory, is an assertion of value.”1

Even in theories that claim neutrality, objectivity and strict political non-engagement, some value judgement – at least the value of non-engage←15 | 16→ment – is always present. Such attitude is rarely banal. Let’s imagine that somebody was investigating Nazism during the World War II and was describing the horrors of concentration camps and racist murders. If he did this without expressing his attitude towards Nazism, his research could contain features of silent approval. If someone cannot express a moral attitude when people are dying and wrongs are inflicted, his theory could implicitly communicate that there is no need to engage in an effort to change the circumstances; it is enough to describe them from a distance. Even if there were no outbursts of immoral action, such as Nazism, such theories always bear conservative tones – they do not problematize the system they are analysing, therefore they are in implicit agreement with it. This also applies to social sciences that try to resolve different manifestations of the political or economic system, starting with the electoral systems and ending with the market economy, without explicitly expressing political or moral attitude. They implicitly confirm the basic ideological notions of liberal democracy or the capitalist economy, but the authors usually do not feel obliged to announce these value preferences at the beginning of their investigations. It’s not a fair game. Objectivity in this field presupposes a battle of ideas, not pretending that our ideas are robotic manifestations of the sociopathic mind that has managed to get rid of all prejudices, values, moral judgements and opinions, and is able to pour out sheer objectivity. This book is not an expression of such hypocrisy. It is leftist and does not hide it. The arguments I use cannot be weakened by this fact: the only thing that can weaken them is a rational counter-argument or empirical proof of the opposite of my claims.

Jean-Paul Sartre argued that an intellectual should be a permanent critic. They can never stop with their criticism, they have to throw away their “provincial reflexes”, they are the guardians of fundamental values. Sartre understands social criticism as a militant engagement in the interests of revolutionary social changes. The approach of a social critic is unconditional and radical. This does provoke negative reactions, contempt and scorn, but the social critic must persist in the criticism of society and promoting universal values regardless of the resistance of conservative forces. The assumption of Sartre’s social criticism is not disinterested distance, but radical engagement.2 Such understanding of social criticism is typical for radical social theories that will be dealt with in this book in defining what is called leftist antiglobalization or antiglobalist Left.

←16 | 17→The forms and approaches of social criticism vary, but in general it can be said that it is trying to create the preconditions for reforms or revolutionary changes in society. The reflections of social critics also differ in the methods of analysis they use. Social criticism can be based on political philosophy, sociology, ethics, social theory, psychoanalysis or economics; in short, various social disciplines can be used for analysis. One can go even further, beyond academic debates where social criticism is conveyed via art and culture, as evidenced, for example, by various radical musical styles ranging from punk rock to rap and hip-hip up to thrash metal. Social criticism is a society-wide phenomenon that is not limited to the academic sphere, but in my work, I will deal with selected problems of social criticism that are part of the academic discourse on globalization.

The reference point of this book is global capitalism3, which brings dramatic negative consequences to the social, economic, environmental, political and cultural spheres. The role of the engaged political theory is not to ignore these negatives. On the contrary, its role is to look for alternatives of development that would allow a more socially just, emancipated and sustainable future. This idea is best expressed by Marek Hrubec: “In the 1960s, the generation of young people in Germany began to ask their parents what they were doing during World War II and how they responded to the existence of Nazi concentration camps. How will we react to the question of how we responded to the current global order, which gives rise to more casualties per year than every year did during World War II? According to statistics, every year about 18 million people die due to poverty and the causes connected with it.”4

There is no time for valueless science. It is time to look for progressive alternatives to global capitalism.

←17 | 18→1.1 Globalization and resistance movement

At the most general level, globalization can be characterized as the emergence of a complex network of interconnections, which means that our lives are increasingly influenced by events and decisions that take place and are approved far from us. The main feature of globalization is that geographical distances are losing meaning and that territorial boundaries, such as borders between nation states, are losing their importance. Globalization emphasizes that the political process is deepening and expanding in the sense that local, national and global events are interconnected in a constant fluid relationship. Like Stanley Hoffman, we can distinguish three basic forms of globalization: political, cultural and economic.5

Political globalization is most evident in the growing importance of international organizations. They are transnational in the sense that they apply they jurisdiction not within a single state but within the international space of several states. These include the United Nations (UN), the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), the European Union (EU), the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the World Trade Organization (WTO), the World Bank (WB) or the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Negative to this process may be the weakening of the nation states’ sovereignty, and hence the ability of national governments to pursue their own social and economic policies. This is related to different forms of imperialism, in which the superpowers expect from smaller and weaker states – under a threat of sanctions or military attacks – that they will adopt such policy, which is in the interest of the big and powerful players in world politics and economics.

In the case of cultural globalization, we are talking about the process, by which, according to Andrew Heywood, “information, goods, and pictures produced in one part of the world are entering into a global flow that wipes off cultural differences between nations, regions and individuals.”6 Such process, which has negative impact on national cultures, is critically named as mcdonaldization. The result is the breakdown of traditional cultures and the replacement of traditional values by Western values of careerism, individualism or consumerism, which are usually concealed by noble values such as freedom, democracy or human rights.

←18 | 19→In traditional communities, an individual is considered as part of the whole, and thanks to their affiliation with the community, they feel secure. The community fulfils social functions. The breakdown of communities, the destruction of traditional cultural patterns and coarse replacement of time-tested experience with the glib Western trade culture has devastating consequences for many communities in the world: it does not bring more freedom to the individual, only more vulnerabilities, alienation and isolation.

However, in the presented monograph, we will mainly be interested in the third form of globalization – the economic one. It is – at the most basic level – expressed by the notion that today no national economy is an island and all economies have been more or less integrated into the interconnected global economy. It has, of course, dramatic effects on the character of the world economy as well as the nation states’ economic strategies. Economic globalization is the primary target of the criticism of the anti-globalization movement.

In the last decades, globalization has been characterized by the gradual opening of economies and introducing the free movement of goods, services and capital. According to Eric Hobsbawm, this process was accompanied mainly by these three economic phenomena:

- the creation of multinational (transnational) corporations;

- the emergence of the so-called offshore companies and tax havens, into which transnational capital has been relocating its headquarters to avoid paying taxes;

- a new international division of labour, i.e. the massive use of cheap labour, especially in Third World countries (after 1989 in the post-communist countries as well) by transnational corporations. The beginning of this process took place after World War II, but it has been in full acceleration since the 1960s.7

This development has brought negative consequences primarily for the institute of the welfare state, which has been one of the fundamental attributes of post-war Western societies. This leads to the deepening of inequality, rising of poverty and unemployment and to the decrease of solidarity in society in general.

As William Robinson explains, the post-war welfare state project was built on three pillars. The first pillar was Keynesian regulation based on the ←19 | 20→assumption that the nation state should intervene in the national economy and redistribute economic benefits to increase the purchasing power of the population, to maintain full employment and to strengthen monetary stability. The second pillar was a Fordist business model, which was based on the fact that the relationship between labour and capital was built on mass production, strong trade unions and tripartite collective bargaining. It was later dubbed social (democratic) corporatism. The third pillar was the Beveridgian social security system, which provided universal social rights for all who happened to live in poverty.

Globalization has disrupted all three pillars of the post-war welfare state:

- the state has lost control over investment flows, therefore the Keynesian regulation of the economy has been considerably hindered;

- due to unlimited mobility, capital has gained a trump card in collective bargaining - it can blackmail states and trade unions by threatening to relocate to other countries with cheaper labour, more liberal labour codes and lower taxes;

- transnational capital has been increasingly successful in avoiding tax payments via “tax optimalization” allowed by the deregulated global economy. The result is a lack of resources in public budgets, which makes the welfare state to become unsustainable.8

The environmental consequences of globalization are also serious. In a society, where social responsibility is disappearing due to the shift of authority from public to private actors, they reach the level when we are struggling for the survival of the planet. As Ulrich Beck noticed, globalization describes the process in which global markets suppress or replace political action and thus refers to the ideology of world market governance, the ideology of neoliberalism, which progresses in many ways, economically, limits the multi-dimensionality of globalization to the economic dimension, that is meant only linearly and all other dimensions – ecological, cultural, political, civic-social globalization – get to language, if at all, only in the subordinate dominance of the world market system.9

Economic globalization is mainly related to the liberalization of international trade, the parameters of which were set in the 1990s by the so-←20 | 21→called Washington Consensus. As Joseph Stiglitz states, the net result of the Washington Consensus policy has too often yielded profit to a few rich at the expense of many poor. Business interests and values have so far too often pushed the interests of the environment, democracy, human rights and social justice to the background.10

However, not only economists take into account the problems that arise from the process of globalization. Philosophers talk about globalization as a variant of the hazardous society from which transnational companies gain their power.11 As Beck points out, there is an increasing risk in a globalized world that is not immediately visible. Radioactivity, greenhouse gases, microbes and pollutants of all sorts are not as visible as natural threats like hurricanes, floods or earthquakes. Risks are mostly depersonalized; they are isolated from specific social actors and it is difficult to pinpoint blame to anyone. However, these risks are global and do not fall within the competence of national governments.12 In this context, Beck writes, that the definition of global risk society goes: the very power and the characteristics that are to create a new quality of security determine the absolute uncontrollability.13

Globalization consequently means a world without control, in which the whole world is being constantly exposed to new risks, stemming from the stern logic of the global market economy. The ideology of neoliberalism tries to present the idea of a free market as the only right solution in the era of globalization. However, as many social critics argue (David Held in this case), this opinion can be criticized in several points:

Details

- Pages

- 342

- Publication Year

- 2019

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9783631775103

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783631783160

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783631783177

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9783631783184

- DOI

- 10.3726/b15687

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2021 (March)

- Keywords

- Global capitalism Marxism Deglobalisation Anti-globalism Alter-globalism Globalisation Communitarianism Liberalism Neoliberalisation Democratic Socialism

- Published

- Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Warszawa, Wien, 2019. 342 pp.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG