Buffers beyond Boundaries

Bridging theory and practice in the management of historical territories

Summary

Using buffers as the main connection thread, this book is a collection of complementary studies that explore the contemporary challenges in heritage definition and management. With a focus on European and Asian historical territories, this book tracks umbrella terms, from their genesis inside international discussions and cultural exchanges, to their specific interpretation in top-down on-site strategies. Then, it originally complements and verifies these official management models with the study of local realities and parallel bottom-up actions that have emerged to fill major gaps in this system. With this, the book underlines the negative impacts of isolated biased strategies, and addresses the call of local intermediate groups and communities for integrated efforts.

Finally, buffers are presented as an intermediate heritage management model that could help integrate both, protection and development, territorial and community scales.

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Acknowledgements

- About the author

- About the book

- Citability of the eBook

- Table of contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Buffer problems

- 1.2 Contemporary problems of buffers

- 1.2.1 Problem of “heritage” theoretical definition

- 1.2.2 Problem of “buffer” theoretical definition

- 1.2.3 Problem of physical definition

- 1.2.4 Problem of practical and legal significance

- 1.2.5 Problem of heritage governance and awareness

- Chapter 2: Study n1. Cultural implications of buffers20

- 2.2 Cultural dimensions of heritage and space

- 2.2.1 The monument and the origins of heritage boundaries

- 2.2.2 Cultural notions of space

- 2.2.3 The nature-culture divide

- 2.2.4 The cultural implications reflected in heritage management in Eastern countries

- 2.3 Exchanges East-West in the UNESCO context

- 2.3.1 Evolution until 1995

- 2.3.2 Evolution until 2010s

- 2.3.3 Recent approaches

- Chapter 3: Study n2. Conceptual roles of buffers

- 3.2 Conflicts in world heritage “buffer” definition

- 3.3 Different buffer characteristics and dimensions

- 3.3.1 Theoretical types by analysis of “World Heritage and Buffer Zones”44

- 3.4 Complementary simultaneous buffers

- 3.4.1 The natures of the different buffer types

- 3.4.2 Simultaneity of buffer types

- 3.5 Expanding or restricting the notion of buffer: the dilemma

- 3.5.1 The “buffer” in the HUL approach

- Chapter 4: Study n3. The morphology of buffers51

- 4.2 The shapes of heritage zones

- 4.2.1 Physical elements defined by heritage zones

- 4.2.2 Defining just one heritage site

- 4.2.2.1 Boundary basic types

- 4.2.2.2 World Heritage area definition strategies

- 4.2.3 Defining sites composed by multiple heritage areas

- 4.2.4 Section conclusion

- 4.3 The evolution of heritage boundaries

- 4.4 The simplification of heritage physical identification

- Chapter 5: Study n4. Buffers in practice62

- 5.2 The management of the historical territory

- 5.2.1. Case A. Aranjuez, reliance on municipal boundaries72

- 5.2.2. Case B. Ferrara, a city and a natural park connected by the rural77

- 5.2.3. Case C. Val d’Orcia, a shared territory91

- 5.2.4 Case D. Thua Thien Hue, monuments over landscapes102

- 5.2.5 Case E. Angkor, an archaeological park isolated from its regional context108

- 5.2.6 Case F. Bali, enclosed sacred agricultural landscapes114

- 5.3 Extensive weak areas or narrow control zones

- 5.4 Disconnection of heritage zones, strategies and tools

- Chapter 6 Buffers vs. heritage management boundaries

- 6.2 Theory vs. practice: The dominance of static restrictive zoning

- Chapter 7: Study n5. Buffers and intermediate groups117

- 7.2. “Ferrara, city of renaissance, and its Po delta”

- 7.2.1 The evolution of the WH site and its partial legislation123

- 7.2.2 Strategies and projects developed with or by intermediate actors in Ferrara

- 7.2.2.1 A creative historical city

- 7.2.2.2 The interpretation of the territory

- 7.2.2.3 Awareness raising

- 7.2.3 Evaluation and future for Ferrara, towards a shared territorial strategy

- 7.2.4 Reassessment on common reflections for Ferrara

- 7.3. “Complex of Hue monuments”

- 7.3.1 Static protection of monumental heritage141

- 7.3.2 Evolution of parallel strategies

- 7.3.3 Evaluation and future for Hue

- 7.3.4 Reassessment on common reflections for Hue

- 7.4. Pending points

- Chapter 8: Study n6. Buffers and communities

- 8.2 The historical ecosystem of the Nguyen Royal Tombs

- 8.2.1 The historical structure of the Nguyen Royal Tombs

- 8.2.2 Tomb protection and management

- 8.2.3 The role of local communities

- 8.2.4 The villages surrounding the Nguyen Royal Tombs

- 8.2.5 The study of culture-nature links

- 8.3 Visualizing tomb-village ecological and cultural links

- 8.3.1 Characterization of the environment of each tomb and neighbouring villages

- 8.3.2 Comparative analysis

- 8.3.2.1 Tomb-village symbiosis before World Heritage registration

- 8.3.2.2 Present tomb-village ecosystems

- 8.3.3 Partial conclusions

- 8.4 “Living buffers”, linking heritage protection and traditional livelihoods

- Chapter 9: A new approach towards buffers

- 9.2 Potential roles of buffers

- 9.3 Prospective of the research: Towards the identification of soft spaces and creative tools

- References

What is a buffer? Is it a boundary, a threshold space or an action area? Trying to answer these questions, this book proposes a shift in approach towards buffer zones, in line with the contemporary transition from the traditional heritage preservation paradigm to the newer ones, which aim at channelling acceptable change in a rapidly transforming world.

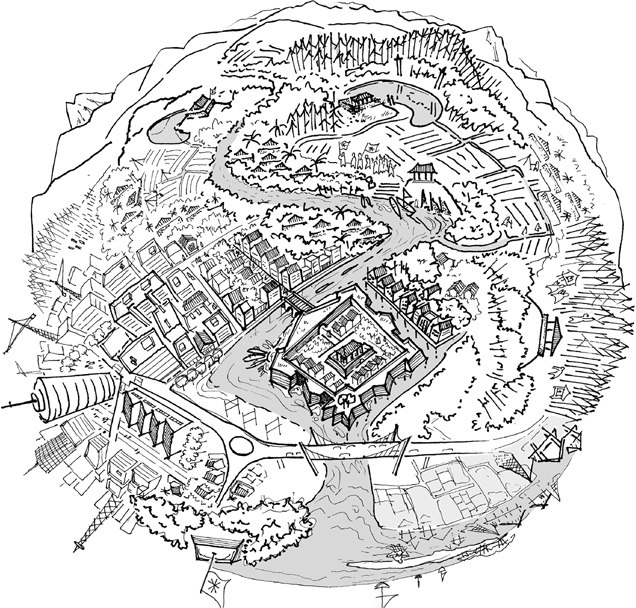

I encourage you to imagine that you are both a manager and an inhabitant of a rich heritage site. It is composed of an old fortified city, which is now inhabited. A wide river crosses the city shaping the physical setting. The old streets face symbolic mountain peaks in the distance and, on the ground, host the daily activities of lively local communities. Upstream, lovely vernacular villages continue their traditional agricultural activity, shaping the mountainous landscape in which they are carefully pierced. Nearby, important monumental scenic groups include water reservoirs, which also support rural productive ecosystems. Farmers manage water and sacred forests surrounding these monuments, exerting strong two-way practical and ritual connections with them. These activities influence soil water retention and the water flow and quality of the river that shapes the city’s close setting downstream. At the same time, in our ideal region, strong urban development and urban-rural migrations have been damaging these traditional systems in recent years. The living conditions in rural areas are harsh, young people prefer jobs in the new urban areas that are emerging next to the historical city, and natural and touristic resources have become important commodities for the regional government that reflect in better infrastructures (Fig 0.1).

Here, you are in charge of defining a comprehensive management strategy that protects all these unique assets while also giving people space to improve their life quality. At this point:

– What would you define as “heritage”?

– Can you define clear boundaries for it? How can you use them in practice?

– How can you protect different heritage values and layers with the local existing tools?

– You want to allow and boost sustainable development, but how do heritage protection tools and zones help/affect your strategy? Who would you partner with?

– How can you address the management of change in regional systems? Inside communities? Where would you limit growth?

– You want to protect and engage local people, but how does your heritage protection strategy affect local communities?

These are just some of the problems I encountered while working as part of the Waseda University (Japan) team, an academic group that ←12 | 13→works as advisor to the Hue Monuments Conservation Centre, in Thua Thien Hue, Vietnam. The case of Hue is a unique example of culture-nature links at small and regional scales. The region is experiencing fast development and demographic changes in recent years, which presents great challenges for conservation. This project confronted me with the task of proposing new management areas and strategies for a rapidly developing cultural landscape. Our team has been looking for solutions that could serve to protect heritage values and assets while also supporting sustainable development based on local unique resources. Thus, our challenge is to integrate protection and positive development. However, traditionally, a strong division of ideas exists: protection opposed to development, culture opposed to nature, urban opposed to rural, which is emphasized by traditional planning tools. Now, we require tools that can go beyond these boundaries.

Fig 0.1 The heritage regional whole (by author)

This journey originates around March 2013. As part of an academic workshop, I was confronted with the task of rethinking a territorial management strategy based on the historical and natural assets of the Hue region. At this stage, all the researchers involved considered issues such as environmental measures, local livelihoods and cultural routes and made great cutting-edge multidisciplinary management proposals. Later, as my participation in the project consolidated, the team began discussing with the local heritage protection agency the redesign of the official management model for the UNESCO World Heritage site in the region. Here, facing the definition of official tools, with the official heritage management bodies, our first thoughts went to protection zones.

Even if we are aware of the multiple intertwined management layers and values in our heritage areas, materializing these connections in a management model is rather difficult. When heritage experts and site managers face the definition of heritage management proposal for the first time, the definition of well-established protection zones and legal and urban measures usually comes up. Even when there is no connection with UNESCO World Heritage and buffer zones, we might find ourselves discussing heritage zoning. However, if I had accepted the generalized idea of buffer as a restrictive zoning tool, this book would have been condemned to limit its discussion to physical limits and legal aspects of heritage management. Luckily, we were aware of some main problems that restrictive buffers presented, which we wanted to avoid.

←13 | 14→At a first glance, I could not see any law or local measure that allowed our team to include the natural and social values in the new heritage strategy. Rather, the only available tools were the monumental heritage protection law and urban development restrictions applied within the defined protection areas. Both referred only to the built environment, creating a strong imbalance between what was inside the protection areas and what was outside. Thus, an extension of the traditional monumental protection zones would be insufficient to protect regional scale cultural landscapes and traditional community links with the heritage sites.

I looked for alternative management models. As a reaction to functional problems of heritage management, new visions have been tested in recent years. One strong emerging model is the Historic Urban Landscape approach (UNESCO, 2011). It presents the historical territory as a layering in which different aspects and disciplines mix to create a whole system. This idea is easily understandable for the case of Hue. But then, concerning management of this layering, it recommends using four generic types of tools simultaneously: civic engagement tools, knowledge and planning tools, regulatory systems tools and financial tools, which have to be adapted for local application (UNESCO, 2016). To understand the on-site application of these tools, we can take other case studies as a reference, but at the time, there was not clear model I could follow. Thus, thinking of an official management proposal transferrable to local management bodies, I could not escape defining core and buffer zones, which were the clearest available tools contemplated in legal systems.

Thus:

– How could I address complex problems with these tools?

– How could I integrate the different recommended tools in my system?

– How could I propose a more inclusive buffer?

– Can this buffer respond to both protection and development?

At this point, I knew I was looking for a model strong enough to control negative pressures but flexible enough to include local culture-nature links and activities. I also knew this model had to match international ideas and have enough recognition to be presented inside an official management strategy. The word “buffer” sounded capable of ←14 | 15→addressing these issues despite the generalized connection of “buffer zones” to restrictive measures. Thus, in parallel to the project, I tried to look for alternative approaches to the definition of buffer. I considered the ones that resulted from literature review, desk work, and analysis of policy documents for other case studies, but also from experiencing diverse buffer definition problems on-site, interviewing regional stakeholders and communities, and putting myself in the position of potential manager and user of such areas.

At the time, I took up the task of developing a comparative analysis of buffers in Eastern and Western heritage territories, traditionally at the two poles of the heritage debate. My aim was to create a reference collection of cases, under similar circumstances, to use as resources for my personal project. Many topics intertwined, so I organized the research as a series of complementary multidisciplinary studies on the application of buffers in historical territories in both world areas. The studies are divided in three main blocks (Fig 0.2) that analyse theoretical, practical and experimental dimensions as follows:

First, the main problems of buffers are summarized and presented in Chapter 1. Chapters 2 and 3 focus on theoretical buffers. In this block, Chapter 2, “Cultural implications of buffers”, studies the dimensions of heritage in European and Asian contexts, and how the idea connects to the use of zoning and management boundaries. It examines the different definitions discussed inside the UNESCO context to highlight the mutual influences of the two world areas in the formation of the actual “heritage” and “buffer” concepts. Then, in contrast to UNESCO’s official definition of heritage buffer, Chapter 3, “Conceptual roles of buffers”, finds diverse complementary ideas on buffers proposed by international experts that could better portray the problems of on-site complex practice.

Chapters 4 and 5 discuss the actual use of buffers. From here, the book presents a critique of the practical use of buffer by decision makers. Chapter 4, “The morphology of buffers”, makes an exhaustive evaluation of the morphology of World Heritage zoning in Europe and Asia. It addresses the evolution of morphological typologies and questions the capacity of the zones to adapt to new heritage concepts. This analysis sets out some new hypotheses. For example, in heritage regions, using simple scattered serial zones rather than identifying bigger regional structures might suggest problems in heritage identification and management. Here, it is necessary to contextualize the typologies in order to contrast these ideas and evaluate their adequacy.

To cover as many heritage layers and possible buffer meanings as possible, this study next focuses on big heritage regions, which are more likely to contain different heritage elements and scales. Chapter 5, “Buffers in practice”, presents six case study sites (Ferrara, Aranjuez and ←15 | 16→←16 | 17→Val d’Orcia in Europe, and Hue, Angkor and Bali in Asia) to examine the practical and legal roles of buffer zones; the case studies represent each one of the tendencies for regional heritage definition identified in Chapter 4. Then, legal and strategic actions for the protection of the historical territory defined in the official reports are reviewed. With this, I was able to understand the ways in which WH boundaries match regional management zones and tools. Based on the results, Chapter 6, “Buffers vs. heritage management boundaries”, forms a critique of the actual definition and uses of buffer zones.

The final block focuses on the heritage dimensions that, although not part of official protection systems, play an essential role in the sustainable development of historical regions. Thus, Chapters 7 and 8 present experimental buffers.

Chapter 7, “Buffers and intermediate groups”, focuses on protection of cultural, natural, agricultural and productive activities. It presents field surveys and interviews with local academic experts, NPOs, site management bodies and government officials that were conducted in Ferrara, Italy, and Hue, Vietnam, and compares them with the management models reported to UNESCO (in Chapter 5). This helps identify complementary actions and support groups that fill the gaps of the official heritage protection models beyond site boundaries.

The final study, in Chapter 8, “Buffers and communities”, uses the case of the Royal Tombs and surrounding villages in Hue to understand the mutual impacts of standard monumental protection buffers and local communities. To do so, a series of group interviews with village leaders were conducted, cultural and activity links identified and the evolution of the areas evaluated.

Details

- Pages

- 272

- Publication Year

- 2019

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9782807612716

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9782807612723

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9782807612730

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9782807612747

- DOI

- 10.3726/b16095

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2019 (October)

- Published

- Bruxelles, Bern, Berlin, New York, Oxford, Wien, 2019. 272 p., 61 b/w ill.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG