The Art of Tifo

Identity, Representation, and Performing Fandom in Football/Soccer

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

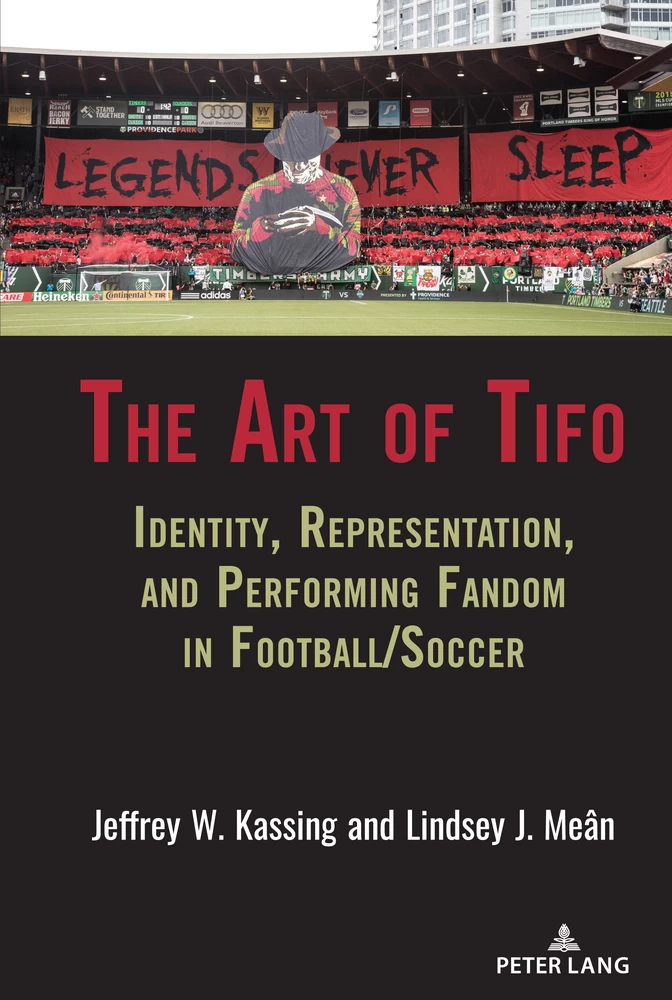

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the authors

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Chapter One: History, Origins, and Evolution of Tifo

- Chapter Two: Football, Identity, and Fandom

- Chapter Three: Demonstrating Dedication and Performing Devotion

- Chapter Four: Memorializing, Commemorating, and Community Building

- Chapter Five: Animating Rivalries and Antagonizing Adversaries

- Chapter Six: Choreographing Politics and Illustrating Social Movements

- Chapter Seven: Commodifying and Commercializing Tifo

- Chapter Eight: Tifo and Modern Sport

- Index

- Series index

Preface

Some years ago, when our daughter first began playing club soccer, we organized an outing to see an upcoming match featuring the U.S. Women’s National Team, which was coming to our hometown. To get the girls excited about the game we introduced them to the tifo tradition. This entailed buying white bed sheets, stitching them together, and outlining a design. The design featured two banners. The first had the club’s name on top (i.e., Inferno) and a giant red heart in the middle, with flames surrounding the heart. The second simply said, in blue font USWNT. It was intended to signify that these girls and their club loved the USWNT. The weekend before the match we hosted a tifo painting party at a local park and the girls completed the banners coloring them in black, red, orange, yellow and blue. We then took the tifo to the game and displayed it, unfortunately without too much fanfare. Nonetheless the girls learned about tifo as a means of demonstrating commitment and support for your favorite team.

Because the tifo included two pieces, we were able to repurpose the larger banner and use it at championship matches for the team. Supported by a large frame constructed out of plastic piping, a small army of parents would hoist it up on the sidelines just before kickoff to inspire the girls. Thus, it appeared several times in the local Phoenix soccer scene, often catching curious glances from opponents and their fans. Years later, a pregame conversation with an assistant referee revealed that she remembered our club because of the “giant sign” we used ←ix | x→to display. So while the original two-panel tifo failed to garner much attention, the subsequent one (featured in the image below) made an impression.

To those unfamiliar with choreographies conducted at football/soccer matches, the spectacle of tifo is captivating and memorable, their origin curious, and the preparation behind them mysterious. This book aims to expose the tradition to a much larger audience, while recognizing and celebrating those who pour their time, energy, and devotion into producing choreographies and displaying tifos.

Partial View of the AZ Inferno Soccer Club Tifo

Source: Author.

Chapter One

History, Origins and Evolution of Tifo

The word tifo means typhus in Italian, a disease characterized by emotional outbursts. In the 1930s, newspapers likened fanatical supporters and their emotional displays to the symptoms of typhus. Over time the term simply came to denote fans and the phrase ‘fare il tifo’ (or ‘doing the typhus’) the active support for their respective clubs (COPA90 Football, 2017). The word subsequently referenced in-stadium displays by ardent supporters. Tifo is often used synonymously with the term choreography, with both connoting organized, pre-planned public spectacles at football matches and soccer games. But tifo also refers to a specific form of stadium display—“handmade, large-scale, and colorful banner displays” (Andon, 2017, p. 165). These are widely “acknowledged throughout the world as helping to create atmosphere and propelling players and teams to perform their best before big matches” (p. 166). And they serve as a means by which supporters can show their unadulterated adoration for their respective clubs “in a grand and material sense” (p. 166). As such, for fans, tifos are a powerful form of visual rhetoric that “use colors, shapes, and images to communicate messages in unique ways” (p. 166). Thus, tifos are an important element of fandom, notably for the performative dimensions of fan culture and the identity claims supporters make (Doidge et al., 2020; Henderson, 2018; Kossakowski, 2017).

Choreography or tifo refer to a class of stadium actions that can include choreos, pyro, flags, small banners, and larger tifo displays or a combination of ←1 | 2→these elements (COPA90 Football, 2017; Doidge et al., 2020). Choreos occur when supporters hold up various colored tiles (i.e., small individual-sized squares or rectangles) to form specific images. This ensues when a predetermined pattern inscribed in the distribution of the tiles becomes evident after they are collectively displayed in unison. These are popular in some of the larger clubs and stadia in Europe (e.g., Barcelona, Inter Milan and Real Madrid). Increasingly, choreos have been produced by clubs rather than by fans. Yet they still require the collaboration of fans and spectators for their execution. Pyro, short for pyrotechnics, refers to the (typically illegal) use of flares and smoke bombs in stadia in many parts of Europe, often in tightly choreographed and organized displays. It is, for example, highly prevalent in Turkish football which has cultivated a reputation for being a tough destination for other European teams in inter-continental competitions (Irak & Polo, 2018). Aware of this tradition, supporters of Russian outfit FC Zenit Saint Petersburg welcomed Turkish club Fenerbahçe with a noteworthy pyro display in February of 2019 for a Europa League fixture (Costa, 2019).1 Zenit supporters stretched for hundreds of yards along both sides of the snow-encrusted boulevard leading to the Krestovsky Stadium as the visitors’ coach arrived. Flames engulfed the Fenerbahçe team as it gradually made the climb uphill as successive supporters lit flares just before the coach passed. This fiery display was impressive not just for the pyrotechnics involved, but also because it extended well beyond the confines of the stadium. This is somewhat unusual given the unwritten expectations governing what constitutes choreographies.

The operating rules for tifos subscribe that traditionally they must be displayed briefly in stadia before matches (although in some cases they get displayed during games), be designed, created, and funded by supporters, and that they avoid corporate sponsorship or promotion. Moreover, they usually take months or weeks of planning to produce and execute, being crafted anonymously and in intense secrecy, to avoid compromising the element of surprise (Dirty South Soccer, 2018). Additionally, they tend to be reserved for pivotal moments like season opening or closing games, cup matches, or important rivalries. While tifo displays can consume entire stadia, especially when they involve large-scale mosaics, it is more customary for them to emerge from behind the goal in the curva or kop end of stadia where the most fervent supporters typically reside (Kennedy, 2013).

An Obscure and Untold History

The history and appearance of tifos has not been well documented. This is perhaps due to their ephemeral nature—disappearing from view before matches, rarely ←2 | 3→reappearing, and usually being destroyed after use. This coupled with the fact that they predate the modern digital media landscape contributes to the lack of information available about when and where they first surfaced and how the tradition spread. Despite a poorly documented past, the tifo tradition has accelerated and amplified in the twenty-first century due in large part to the capacity to document, catalog, grade and preserve tifo images worldwide. These same forces have elevated the power and significance of tifo as a mechanism for identity performance and as a site for social and political commentary—themes revisited later in the book.

Tifos originated in Western Europe in the 1960s and 1970s and spread across the football/soccer playing world (COPA90 Football, 2017). According to some, supporters of Italian club AC Milan birthed both the ultras tradition and the custom of stadium displays. The first large-scale tifo banner, which covered the Curva Sud (the section which came to be associated with the club’s ultras culture), appeared in 1984 and featured black and red horizontal stripes and the words “FORZA VECCHIO CUORE ROSSONERO” or “COME ON OLD RED & BLACK HEART” (COPA90 Stories, 2019a). In 2017, FC Barcelona commemorated the club’s first mosaic display, which featured in a clásico matchup against archrival Real Madrid in 1992. A simple design by today’s standards, the tifo created by 20,000 fans at the north end of the stadium included the club nickname ‘BARÇA’ (FC Barcelona, 2017). In the ensuing 25 years the club produced 69 mosaics, with the majority at the club’s home ground (Camp Nou), but also at other locations in Europe where the team contested European competition finals. The commemorative post asserts that “Barça were the first club in Europe to take the mosaic idea to another level with regards to size, the first examples dwarfing the smaller examples that were common in Italy at the time.” (¶ 2). The club’s choreographies have grown over the years to include more than two dozen that have covered the entire stadium, the first appearing in 1994 (MARCA, 2015)—with a mosaic comprised of the club colors that borrowed a line from the club anthem, which read “Blaugrana al Vent” (Blue and Scarlet in the Wind). While the original mosaic was attributed to the Almogàvers supporter group, the club assumed responsibility for organizing mosaics in 1999.

A Global Phenomenon

Although tifo displays historically emerged in Europe, they can be found in India (Bandyopadhyay, 2020; Roy, 2019), Asia (Swaby, 2015a), Africa (Koundouno, 2019), North and South America (Bachman, 2019; Edwards, 2013a) and Australia (A League, 2015). Across the globe they tend to be far more prevalent at ←3 | 4→professional club matches, but can be seen occasionally at international ones too. For example, Brazil fans displayed a large tifo, shaped and painted to represent the Brazilian national team jersey, before a World Cup match in Durban, South Africa in 2010.2

Details

- Pages

- X, 194

- Publication Year

- 2022

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781433167164

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433167171

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781433167188

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433167225

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433167157

- DOI

- 10.3726/b15379

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2021 (December)

- Keywords

- football soccer supporters fandom ultras identity performance representation politics rivalry commemoration commodification The Art of Tifo Jeffrey W. Kassing Lindsey J. Meân

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Oxford, Wien, 2022. X, 194 pp.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG