Teaching the Struggle for Civil Rights, 1977-Present

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the editors

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Foreword (Paula Groves Price)

- Preface to the Book Series: Teaching Critical Themes in American History (Caroline R. Pryor)

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction (John A. Moore, Adam I. Attwood, and Matthew R. Campbell)

- Section 1: Historical Analysis and Pedagogical Issues

- Chapter One: An Historical Inquiry into the Origins of Dr. Martin Luther King Day (John H. Bickford)

- Chapter Two: The Case for Reparations: Breathing New Life into an Old Idea (Gregory Simmons, LaGarrett J. King, and Molly Pozel)

- Chapter Three: Toward a New Frame: Teaching Reparations as a Civil Rights Struggle (Amelia Wheeler and Chantelle Grace)

- Chapter Four: Visibility Narrative Approach to Civil Rights Instruction: One Educator’s Story (Alana D. Murray)

- Chapter Five: Black Economic Self-Determination in the Struggle for Civil Rights: Teaching Black History in Age of High-Stakes Standardized Testing (Jenice L. View and Andrea Guiden Pittman)

- Chapter Six: An Inquiry Model for Teaching the Black Lives Matter Movement Using the Culturally Relevant Community of Learners and Educators (CRCLE) Approach (Chrystal S. Johnson and Cornelius Bynum)

- Chapter Seven: “We Don’t Share the Same Values”: Teaching About Commissions on Police Misconduct (Mark Pearcy)

- Chapter Eight: Matthew Shepard and the Struggle for Civil Rights, 1998 and Today (John H. Bickford and Autumn Frykholm Damann)

- Chapter Nine: Social Justice in the Eye of the Storm: Strategies for In-Service Teachers to Address Social Issues Affecting Students in 6–12 Classrooms (Zakia Y. Gates)

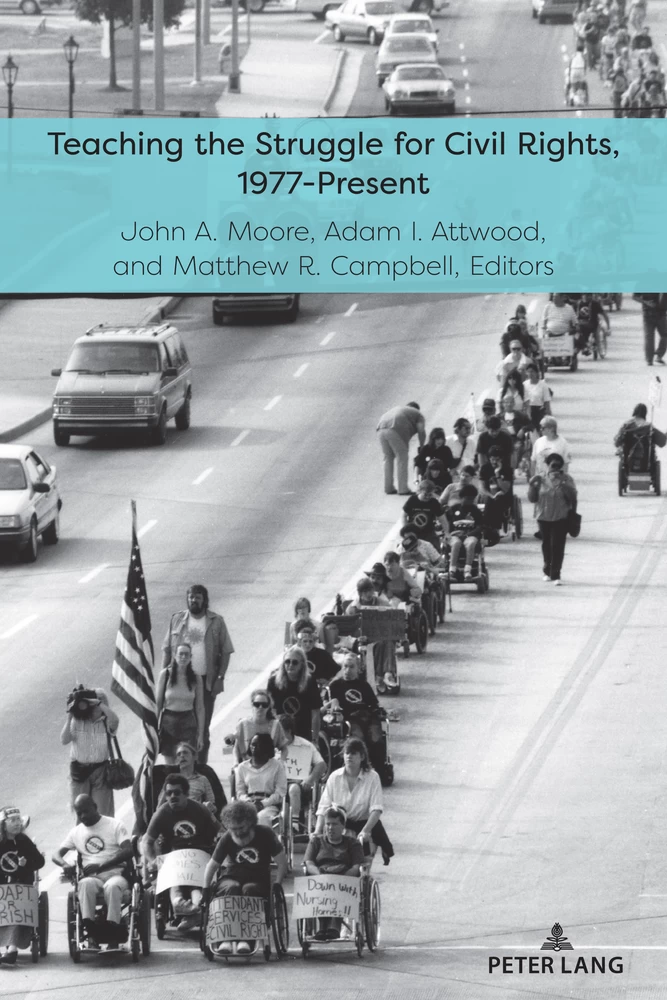

- Chapter Ten: The Civil Rights Movement’s Oft-Forgotten Element: Civil Liberties of Citizens with Disabilities (John H. Bickford and Dalani Little)

- Chapter Eleven: The Economics of Illegal Immigration: Can We Afford to Shut Our Southern Door? (Michael McDonald and John A. Moore)

- Chapter Twelve: A Call to Action: Pedagogical Strategies to Address the Modern Civil Rights Movement in the Secondary Science Classroom (Nancy Nasr)

- Chapter Thirteen: AmeRícan Storytelling: Puerto Rican Civil Rights Artist and Activist Jesús Abraham “Tato” Laviera (Elizabeth Taveras Rivera and Raquel M. Ortíz Rodríguez)

- Chapter Fourteen: Teaching Civil Rights Law in Middle School and High School Civics Curriculum (Adam I. Attwood)

- Section 2: Resources

- Chapter Fifteen: Resources (Caroline R. Pryor, Whitney Blankenship, Charlotte Johnson, James Mitchell, and Amy Wilkinson)

- Chapter Sixteen: Exploring Methods for Teaching Modern Civil Rights (Matthew R. Campbell)

- Note on Contributors

- Index

- Series Index

Foreword

Paula Groves PriceDean and Professor, College of Education, North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University

Today is February 1—a day of great significance to my university. It is the day that we pay homage to the legacy of the North Carolina A&T “Greensboro 4.” It is the day that four freshmen students in 1960 sparked a national sit-in movement by sitting at the “whites only” lunch counter in Woolworths, refusing to leave until the store closed. Their courage to stand up against injustice by taking action is utilized as a reminder to current students that they have great power to instigate change.

It is also 2021. A time where social studies standards are being revised and debated in many states. At the core are questions about the inclusion of the voices, cultures, and perspectives of Black, Indigenous, and people of color and the civic mission of schools to develop thoughtful and informed citizens. While conservatives have always argued for sanitized versions of US History, where truth-telling and multiple perspectives are sacrificed for a single narrative to propagate patriotism, the assault of the Capitol building on Jan 6, 2021 is a stark reminder of the dangers of lies and untruths. Teaching truths and facts are important as ever. Democracy is fragile and an informed citizenry capable of critical thinking, civil and civic engagement, and an ability to understand multiple perspectives is essential. The reality is, today’s middle and high school students have grown up in, witnessed, and in some cases participated in the March for Our Lives, Black Lives Matter protests, marches to save the environment, and women’s marches with their peers and families. They see violent viral videos of systemic ←xi | xii→and institutional racism and discrimination, and they are connected to each other virtually in almost all aspects of their lives. They are learning and surviving in a pandemic, and engaged in social media where they exercise their voices daily. They demand nuanced narratives and have a desire to understand deeper how systems and structures of inequality were developed, and how they can be agents of change.

Teaching the Struggle for Civil Rights, 1977-Present is a timely volume that helps students recognize that the history they are currently living is part of a larger legacy of civil rights. Providing intersectional topics that span a number of diverse historical and contemporary issues, teachers are encouraged to provide opportunities for students to take informed action. Expanding discussions of Civil Rights to include struggles for immigrant rights, students with disabilities, gender identity and expression, the law, and race, the chapters offer teachers concrete ways to teach students to be critical consumers and producers of history.

Working from home while my children engage in school virtually during this pandemic has afforded me many opportunities to see elementary and middle school teaching and learning. While I work on reports and proposals, they often gather nearby and work on their respective assignments. My 13-year-old pays close attention to what is happening in the world, especially in politics. Much like her mother, she is a critical race feminist, and is passionate about issues of racial and gender equality, especially LGBTQ+ rights. Her schooling experiences, as often one of the only or few African American children in all white classroom spaces, has required us to engage early in deep conversations about race, to help her make sense of her experiences and feelings. She is still learning to find her voice in the classroom, but she has developed the critical thinking skills to question narratives.

Teaching the Struggle for Civil Rights, 1977-Present is a gift for teachers and students like my daughter. The chapters provide context, understanding, multiple perspectives, and more formalized ideas for students to discuss the topics and issues that are relatable to their lives. Perhaps more importantly, they call young people to take informed action in support of humanity.

Preface

Caroline R. Pryor, Series Editor, on behalf of the Editorial Team, Erik Alexander, James Mitchell, Whitney Blankenship, Char Johnson, Jenice View and Michael Karpyn

About the Book Series Teaching Critical Themes in American History

In working with teachers who had developed lesson plans for our earlier publication on Abraham Lincoln, the theme that we (Pryor & Hansen 2014) most often discussed was the nature and embodiment of civil rights and civil liberties. We learned from teachers who participated in our workshops that the challenges of teaching main events of the Lincoln era were many—however, the larger challenge was how to teach critical themes of this era, such as the topic of slavery—and civil liberty. A challenge for these teachers had been how to address critical issues emanating from Lincoln’s announcement of the Emancipation Proclamation. What role would newly free slaves have? Would they be citizens? If citizens, what rights would they have (e.g., the right to vote). From this experience, we wondered what content and pedagogical resources teachers might need to more deeply address the critical issues of all of American history—civil liberties and civil rights.

These and other questions continued to emerge as we developed the volume topics for this series. Our goal was to provide students a more robust experience when learning about historical events. As the editorial team developed the topic for each volume, we also noticed numerous challenges of teaching topics embedded within each of these themes. Then, as early volume proposals were submitted ←xiii | xiv→to us, prospective editors pointed to the lack of attention most school textbooks place on the theme of human need and social response. We drew from this pedagogical challenge the need to describe the political philosophies underlying the American historical narrative, a journey of personal freedom.

Book Series Organization

The series was initially composed of ten separately titled books examining a different significant problem/critical themes in American history. Having published the first few of these titles, we expanded the series to include additional titles such as Women’s History and two volumes on the United States Constitution. Each volume contains disciplinary content in American history, a discussion of disciplinary connectedness linking past and present thematic issues, a discussion of the pedagogical challenges in teaching that content, examples of lesson plans, and resources teachers could use in the classroom. Each volume address the Common Core Standards (CC) adopted by forty-six states (http://www.corestandards.org), the C3 Framework (C3.ncss.org) and the National Curriculum Standards (NCS) of the National Council of the Social Studies (ncss.org).

This series provides teachers an examination of critical themes in American history with resources to teach these themes. The resources found in this series are: (a) historical content for exploring critical themes (b) historical context for addressing the themes of civil liberties and rights, (c) examples of how to use national standards to augment lessons, and (d) primary and secondary source material to support the investigation of critical themes in American history.

Moreover, the Peter Lang website provides links to the Series website—which contains a range of teaching resources such as links to primary documents, secondary literature, and projects that the teacher can assign to students.

Teaching the Struggle for Civil Rights, 1977 to Present

This series of volumes began as an introspective on themes often less discussed in public schools, grades 7–12. As the series progressed, the theme of civil rights emerged from the contributors’ essays, lesson plans and resources and served to focus the approach to our series. It appeared to us (the editorial team), that we truly are a nation that began our exploration of civil rights much earlier than is typically taught in schools. In part, as John Marshall Harlan chided in his discussion [dissent] from Plessy v. Ferguson (see Thernstom & Ravitch, 1992)—the nation’s forging was grounded in civil liberty and codified, albeit imperfectly—in ←xiv | xv→civil rights. It is to this end, the exploration and importance of the historical journey of civil rights that we present the editorial leadership of John Moore, Adam Attwood and Matthew Campbell and their volume authors.

More deeply, we present, as does John Moore in his dedication to the late Congressman John Lewis, and Paula Groves Price in her Foreword to this volume, a compendium of ideas generated by those who have long shouldered the work of civil rights. While the ideas presented in this volume are but a part of a larger historiography, they are a beginning—a foundational discourse on generating conversations with and for our students.

We begin by seeking guidance about a definition of civic order, that is what ideas guide interactions within our communities, such as voting, and what could be thought of as residing in a more personal realm, such as personal speech or writing. In many cases, these ideas meld or appear so integral that they might not be thought of as separate constructs.

For simplicity, we draw on the presentation of Diane Ravitch and Abigail Thermston (1992) who write that John Locke’s 1690 Second Treatise of Civil Government, was foundational to [democratic] civic order in its repudiation of absolute monarchy. Here then we see the case for what we term in this book series as civil liberty, a vision of social construct under law, rather than domination by reign (see the Massachusetts’s Body of Liberties, 1641).The focus of Locke’s discussion of liberty encompassed the need to codify personal freedom (civil rights).

Cornell University’s School of Law’s Legal Information Institute offers this definition:

Civil rights refer to legal provisions [emphasis added] that stem from notions of equality. Civil rights are not in the Bill of Rights; they deal with legal protections. For example, the right to vote is a civil right. A civil liberty, on the other hand, refers to personal freedoms protected by the Bill of Rights. For example, the First Amendment’s right to free speech is a civil liberty (https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/civil_rights).

In this brief preface, we note two themes that emerged in the struggle for civil rights in the era of 1977 to present. First, we note the importance of currere—looking back in order to look forward (Pinar & Grumet, 1976) as we read the foundational work of Whitney Blankenship, editor of the preceding volume in this series, Civil Rights, 1948–1977, and her authors as they proffer discourse on historical and philosophical void. Here Dr. Blankenship and colleagues explain civil liberties—political and communal social freedoms that lacked the national codification needed to promote equitable standing among our citizens. In her volume, Blankenship provides an overview of a range of civic gaps, many emanating from legal restrictions such as those imposed on participation in voting.

Second, we note that this current volume scaffolds the theme of civic restrictions to illuminate the rationales for their (albeit incremental) erasure. This ←xv | xvi→volume provides insight on the expansion of liberty exemplified by the codification of personal civil rights. In the early to mid-1960s personal right had not yet been extended to a range of inequities such as gender or disabilities. The late 1960s however, began an era in which the grip of entrenched inequities was slowly eradicated (e.g., the Elementary and Secondary Act, 1965; the Bilingual Education Act, 1968; the Federal Title IX legislation, 1972, and the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, 1975–2004).

In this current volume the authors provide perspective on historical events from the late 1970 era to present, and suggest that many public school textbooks lack the narrative to broadly present the topic of civil rights in the “available light” (Gertz, 2000) of contextualized controversy and public resolve. The discussions in this volume begin with the mid to late 1970s which sought both social collaboration and notable confrontation as seen for example in John Bickford’s chapter on historical inquiry on Dr. Martin Luther King Day and Elizabeth Taveras Rivera and Raquel Ortiz Rodriquez’s chapter on Puerto Rican culture and art as inquiry.

Examples of the history of these foci are seen in Alana Murray’s chapter on making civil rights history and instruction a visible story. Additional chapters illuminate these themes, which over the course of fifty years, have provided deep scholarly examination.

As an editorial team, we offer the work of John Moore, Adam Attwood and Matthew Campbell and authors of the volume’s essays, lesson plans and resources in the spirit of academic inquiry into how teachers might exempt students from propositional certitude and historical narrowness.

Acknowledgments

With appreciation and acknowledgment to the Series Editorial Advisory Board for their work, insights and dedication to teachers, students, and the production of this series.

Whitney Blankenship, Laura Milsk Fowler, Brian Gibbs, Michael E. Karpyn, Julianna Kershen, Jack Sevin, Mary Stockwell, and Dennis U. Urban Jr.

We also appreciate and acknowledge:

Stephen L. Hansen for his vision in bringing critical historical issues to the forefront of how teachers and students might discuss history.

Patricia Mulrane, Peter Lang Publishing, for her flexibility and openness in testing new constructs and her helpful suggestions to bring these about. To our respective universities for their support of our academic endeavors.

Introduction

John A. Moore, Adam I. Attwood, and Matthew R. Campbell

This book is a collection of points of view from teachers, school administrators, and professors from across America who have come together here to share perspectives on civil rights education. These chapters are written in themes to the legacy of the late Congressman John Lewis. As John A. Moore explained in the Dedication of this book to the late John Lewis, Congressman Lewis is quoted as saying: “When historians pick up their pens to write the story of the 21st century, let them say that it was your generation who laid down the heavy burdens of hate at last and that peace finally triumphed over violence, aggression and war. So I say to you, walk with the wind, brothers and sisters, and let the spirit of peace and power of everlasting love be your guide.”

Details

- Pages

- XVIII, 296

- Publication Year

- 2022

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781433189616

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433189623

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781433189630

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433189609

- DOI

- 10.3726/b19674

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2022 (May)

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Oxford, Wien, 2022. XVIII, 296 pp., 4 b/w ill., 7 tables.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG