Decolonizing Environmental Education for Different Contexts and Nations

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

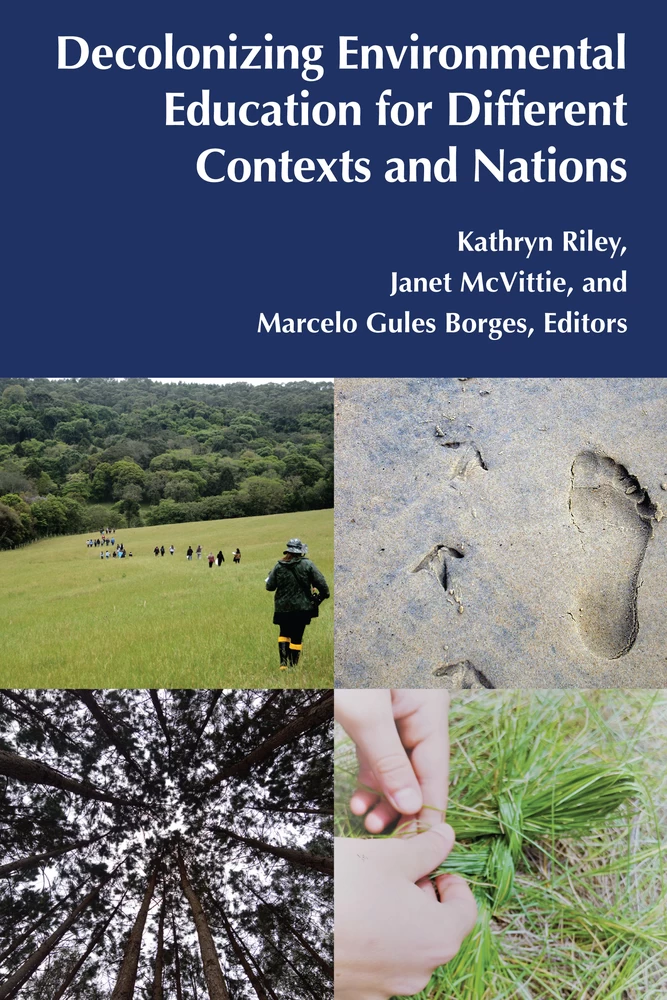

- Cover

- Advance Praise

- Title

- Copyright

- About the editors

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures

- Note from the Series Editors

- Acknowledgments

- Abbreviations

- Decolonizing Environmental Education for Different Contexts and Nations (Janet McVittie)

- A Global Assemblage (Zuzana Morog)

- 1. Integrating Social and Ecological Justice Inquiry (Vince Anderson)

- Water Deep (Sky McKenzie)

- 2. Mutually Entangled Futures in/for Environmental Education (Kathryn Riley)

- Ahora Adentro (Araceli Leon Torrijos)

- 3. Decolonial Pedagogy, Agroecology, and Environmental Education: Repositioning Science Education in Rural Teacher Education in Brazil (Marcelo Gules Borges)

- 4. Taking Learning Outside (Alice Johnston)

- Walking Gently … Through a Cultural Lens … (Kylie Clarke)

- 5. Decolonizing Education for Sustainable Development (Roseann Kerr)

- 6. Decolonizing Environmental Education in Ghana (John B. Acharibasam)

- Earth Sorrow (Elsa McKenzie)

- 7. Naturalized Places, Indigenous Epistemology, and Learning to Value (Janet McVittie & Marcelo Gules Borges)

- 8. Environmental Education through Indigenous Land-Based Learning (Ranjan Datta)

- Escolas Marginalizadas e Educação Ambiental/Marginalized Schools and Environmental Education (Julio Karpen)

- 9. “From the Stars in the Sky to the Fish in the Sea” * (Kai Orca)

- Epilogue

- About the Authors

- Index

List of Figures

Figure 2.1:Buddy at the Saskatoon Zoo and Forestry Farm

Figure 2.2:Cartesian Representational Knowing

Figure 2.3:A Rhizomic Assemblage of Relations

←ix | x→

Note from the Series Editors

We are very pleased to introduce Decolonizing Environmental Education for Different Contexts and Nations, the third volume of the book series (Post-) Critical Global Childhood & Youth Studies. This edited volume pushes us to expand existing theories and approaches to environmental education and to consider new possibilities for exploring, understanding and embracing situated knowledges across diverse contexts in countries such as Canada, Australia, Brazil, Ghana and Bangladesh. This investigation supports an important debate on our mutually entangled futures—in Kathryn Riley’s words, which is crucial at a time when environmental and public health crises are destroying the livelihoods of those least responsible for these. As the authors of this volume argue, there is an urgent need to trouble and challenge the Western worldview that dominates science, society and education in the twenty-first century.

We hope that this third volume of (Post-)Critical Global Childhood & Youth Studies highlights the importance of the exchange of ideas on contemporary issues affecting children and young people around the world while exploring possibilities for local and global social change, which is indeed the focus of the Series. The Series encourages novel approaches to co-producing knowledge in fields such as: urban, rural and Indigenous childhood & youth; children’s rights; social policy, ecology and youth activism; faith communities; immigration and intersectionality; mobile Internet, digital futures, and global education. It discusses the geopolitics of knowledge, and decolonial and anthropological perspectives, among others. (Post-)Critical Global Childhood & Youth Studies is addressed to relevant scholars from all over the world as well as to global policy makers and employees at international organizations and NGOs. This book is indeed an invitation to draw upon such different fields of expertise and areas of activity, and to co-develop a ←xi | xii→different environmental education from within the most diverse cultural and geographic contexts.

São Paulo, Shanghai, Toronto, Buenos Aires & Leeds, October 2021

Series Editors

Acknowledgments

This book is a collective process of decolonizing ourselves. It emerged as a result of sharing our experiences, listening, and standing in solidarity with Others, despite our often-diverging perspectives as situated in different contexts and nations. Decolonizing Environmental Education for Different Contexts and Nations describes individual and collective paths of reflection, animated by history and stories that connect environment and education through, and from, different lands and territories. Over the last two years we have organized meetings and have exchanged thoughts, materials, arguments, challenges, and hopes through our work and actions in our contexts. Based on these conversations, we connected contexts and nations, proposing not to produce a guide on how to decolonize environmental education, but, above all, make explicit our effort to change priorities and decenter human cultures in, and for, environmental education. Most of the authors in this book contributed throughout the meetings, others contributed through their connections with authors in the book.

First, we would like to acknowledge the work from Márcia Mascia, Silvia Grinberg and Michalis Kontopodis in editing this series. We are especially grateful to Michalis Kontopodis for helping us with our book proposal and moving us forward to conclude the book. Our thanks to Juliano Camillo for first connecting ideas of this book with Peter Lang. Thanks also to Dani Green, our primary contact at Peter Lang.

We are grateful to all of you from our contexts that helped us in the process of decolonizing our philosophies, theories, and practices: Rodrigo Ramirez (in memoriam), Buddy, the grey wolf, the doctoral research award from the International Development Research Centre (IDRC), the Dr. Rui Feng Geological Sciences Graduate Studies Award (University of Saskatchewan, Canada), and The University of Saskatchewan Ph.D. Fellowship. Thank you ←xiii | xiv→to the Laitu Khyeng Indigenous Elders, knowledge holders, leaders, and youth participants and to the Campesinas and Campesinos for your warm welcome into your communities and for patiently sharing your stories and knowledge about sustainability and land and water management. Thank you to Marla Guerrero Cabañas, the coordinator of the Calakmul field team of Fondo para la Paz for your trust, openness, time and friendship, and the facilitators and community technicians of Fondo para la Paz: Reynaldo Zepahua Apale, Ezequías Hernandez Torres, and Gelasio Maldonado de Paz for your accompaniment, kindness, patience, and humor. Thank you to the community of La Loche for your trust in the education of your youth, and for your compassion, humor, forgiveness, and kindness. Marci Cho!

We are also grateful for the authors and artists that contributed to this book. We would like to especially thank Juliano Camillo, Zuzana Morog, Vince Anderson, Sky McKenzie, Araceli Leon Torrijos, Alice Johnston, Kylie Clarke, Roseann Kerr, John B. Acharibasam, Elsa McKenzie, Ranjan Datta, Julio Karpen, and Kai Orca. We also thank Jebunnessa Chapola for her insightful contributions to our conversations. We also extend our deepest thanks and love to our families: Trevor, Zuzana, and Charlie Morog, Erin and Natalie McVittie, Iain, Ragnar, Rowan Phillips, and, also, Daisy, Francisca and Samuel Sampaio, and the four-legged friends that make our family complete. Lastly, but certainly not least, we extend our heartfelt gratitude to the Earth that sustains us: the critters of land and sea, the energies, sky, land, waters, and First Peoples that teach us there is a more gracious and reciprocal way of living on, and with, this finite planet.

Abbreviations

| CaC: | Campesino-a-Campesino |

| CHT: | Chittagaong Hill Tracts |

| DW-K: | Dominant Western Knowledges |

| DWW: | Dominant Western Worldview |

| ECEE: | Early Childhood Environmental Education |

| EE: | Environmental Education |

| EfS: | Education for Sustainability |

| ESD: | Education for Sustainable Development |

| IK: | Indigenous Knowledges |

| KG2: | Kindergarten 2 |

| LEdC: | Licenciatura em Educação do Campo |

| MST: | Landless Workers Movement |

| NAAEE: | North American Association of Environmental Education |

| PHG: | Prairie Habitat Garden |

| RCAP: | Royal Commission on Aboriginal People |

| TC: | Community Time |

| TEK: | Traditional Ecological Knowledges |

| TRC: | Truth and Reconciliation Commission |

| TU: | University Time |

| UFSC: | Federal University of Santa Catarina |

| UCC: | United Church of Christ’s Commission for Racial Justice |

| UN: | United Nations |

| UNEP: | United Nations Environment Program |

| UNESCO: | United Nations Education, Scientific, and Cultural Organization |

Decolonizing Environmental Education for Different Contexts and Nations

Janet McVittie

Be good to the planet. It is where I keep all my stuff. (Anonymous)

Introduction

Environmental Education (EE) as a discipline has its roots within the Dominant Western Worldview (DWW). The release of Rachel Carson’s book, Silent Spring, in 1962 (1962/2002), affected the way White, Western people thought about humanity’s interventions in ecosystems. Until then, White, Western people acted, in general, as if they were the only members of the only species that mattered, and the planet’s resources were for their consumption.1 This relatively small and wealthy set of humans did not include even those marginalized within their nations, such as Indigenous peoples; it certainly did not include those from outside of Euro-America (which includes those parts of North and South America where people of European ancestry form the majority of the population), Australia, and New Zealand. Interestingly, now that more researchers are examining Indigenous Knowledges (IK), there is more clarity about what it means to live sustainably, in recognition that the planet is finite. Carson’s book should have pushed people to examine their world views, but this examination has taken some time.

Seawright (2014) argued that DWW (he used the term “settler epistemology”) has created injustices. He noted: “The dominant epistemology of settler society provides racialized, anthropocentric, and capitalist understandings of place” (p. 554). He goes on to argue that without an understanding of settler epistemology, a person will be unable to resist appropriately. DWW is characterized by the belief that humans (particular humans—male, heterosexual, White) are superior to all other entities (an anthropocentric view), that ←1 | 2→the planet and its resources are here for the particular use of these humans, that land should be privately owned (a particular focus of Seawright’s is on the claiming of land), that capitalism and democracy are the only appropriate approaches to human politics and economy, that the economy must be constantly growing, that most things can be organized into dichotomies—good & bad, female & male, black & white, night & day, nature & culture, wild & domestic, etc. Responding to these binary logics, Kai Orca, in Chapter 9, focuses on the damage done by dichotomies, connecting the violence done to children by assigning gender to them at birth, to the violence done to nature by naming it as separate from humans. Further, Kathryn Riley, in Chapter 2, draws on posthumanist perspectives to generate an interactive relationship, an assemblage, with Buddy the grey wolf. In this way, she works to (re)configure oppositional and dualistic difference and (re)draw subject/object boundaries, while also challenging the subsequent hierarchical ordering based on this difference.

The authors of the chapters in this book are a group of educators with a common interest in environmental education (EE), coming together through different wayfaring routes from different points of origin, including Africa (Ghana), Asia (Bangladesh), Australia, North America (Canada, Mexico, United States), and South America (Brazil). As a multi-dimensional group, we are learning about different places and contexts. In all locations we derive from, there are social and ecological issues that need to be resolved.

Details

- Pages

- XVIII, 254

- Publication Year

- 2022

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781433191831

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433191848

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781433191855

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433191749

- DOI

- 10.3726/b18830

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2022 (May)

- Keywords

- Environmental Education Decolonization Settler/Indigenous Relations Dominant Western Worldviews/Situated Knowledges Indigenous Knowledges Socio-ecological Justice Two-Eyed Seeing Land-based Learning Agroecology Food Sovereignty Transecology Transgender

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Oxford, Wien, 2022. XVIII, 254 pp., 7 b/w ill.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG