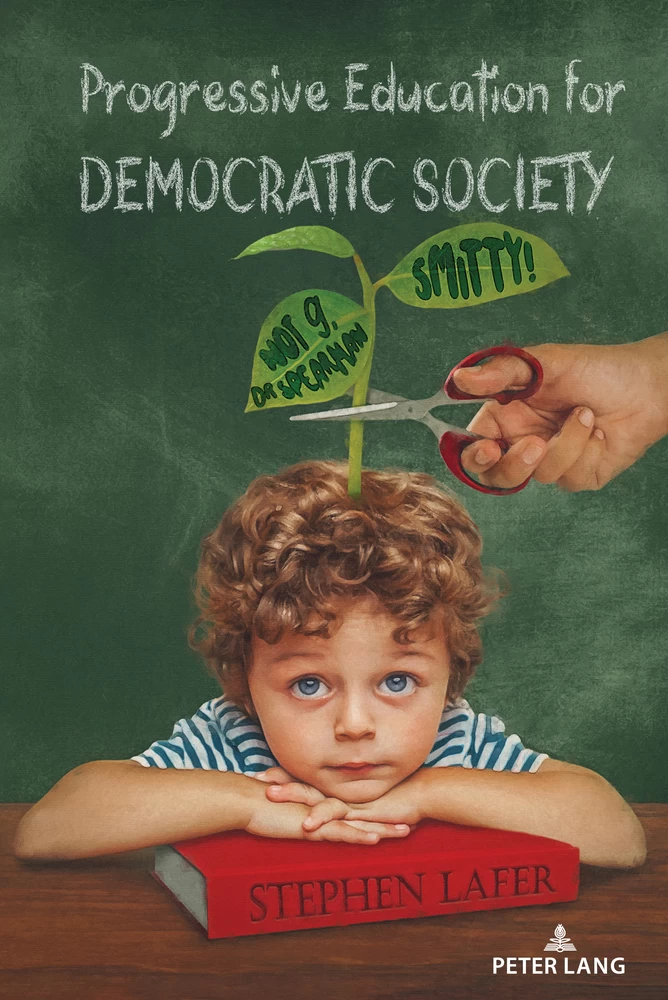

Progressive Education for Democratic Society

Smitty! Not g, Dr. Spearman

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- 1 A Rationale and Evidence

- 2 Ortega y Gasset. Ant-man and the Wasp

- 3 Autobiographical

- 4 Smitty Appears to Labor

- 5 Psychology, Statistics, Reals Students, and Real Democracy

- 6 Truthful Elegance in Science and Truth in Fiction

- 7 Mind

- 8 Trained to Be Predictable

- 9 Chronic Psychology

- 10 Spearman and the Reduction of Mind to g. Psychometrics and the Court

- 11 Basic Humanity and the Inhumanity of the “Basics”

- 12 Progressivism and the Reactionary Response

- 13 Conservatively “Effective Schools.” Moving Progressively

- 14 No Child Left Behind versus The New Standards

- 15 On Writing and Thinking

- 16 A Better Classroom Environment

- 17 Huckleberry and Holden and the Sane and Humane Democracy

- Index

1

A Rationale and Evidence

I have been a student of education for a lifetime. I have been a subject of my own studies since I can remember. Nursery school. Fairfax Boulevard, a few doors down from Harry Bennet’s barbershop where Harry, an old friend of my father from Detroit, cut my hair when I went to Fairfax Boulevard in those days. Haircuts meant sitting still for what seemed a very long time. Nursery school meant sitting for very long stretches of time, too. Harry’s was a short wait for freedom. Harry and my dad would entertain with stories of their youthful adventures. At nursery school nothing done for me helped much to pass the time, and, worst of all, they made me take naps every day, at an appointed time, whether I was tired or not. I usually did not fall asleep. I can still recall, with some discomfort, what it was like being awake in the dark. I remember the inescapable boredom. They controlled every aspect of my being, and they, though always nice, were my keepers. They managed me and my time. They sapped my energy to keep me calm, and so I became listless and detached. I learned daydreaming as a means for getting through the sixty minutes of each hour and the five hours each school day. I did learn to count seconds.

Of kindergarten, I remember only too well the heat through the high windows that warmed the smell of the thick grey braded carpet on which we sat cross-legged every day and on which some of us peed fearing for some reason to ←1 | 2→raise a hand to ask permission to go to the bathroom. The sun warmed the pee in the rug. I counted dust particles then and easily forgot to listen to what the teacher was saying after hearing so much that did not interest me. I wanted to be home. Sherriff John and Engineer Bill were interesting. The holes I was digging on the side of our apartment building for a swimming pool, the rocks in the alleyway, the bees on those sweet-smelling flowers, the water running down the street below the curb, the stick dams and the sand dam and dams made with my finger to change the course of the flow were interesting.

I did get to the junior high school and through high school, reluctantly, as I will later explain, and without enthusiasm enough to gain value from study in which I hardly engaged. Value came later as those early experiences with the tedium school authorities forced me to tolerate led me to thinking about school and why it was ever devised, why it was as it was, and what could be done to make it better or whether it should exist at all. I have thought a lot too about me, as a student-nonstudent and how I was and who I was, who I thought myself to be, as my experiences with school taught me to think of that self. School, in our society, influences a student’s sense of who he or she is and what it means to be the particular me one understands oneself to be.

I did become an educated person, in spite of the system, I believe, and I went on to earn higher degrees from good schools despite many warnings that my low grades and bad behavior would likely prevent such from happening. I studied English as an undergraduate because in my last years of high school I met characters in books who were at least as bad as I had come to think myself to be, but really good deep down in their souls. They introduced me to the possibility of looking at the world academically in ways that were liberating, that upheld liberation as a path to being not just good but very good. I became an academic of, and for the possibility of, liberation, and my purpose was to offer the gift of liberation to others from a repressive system of education that serves a repressive society that could be a democratic one with the help of a decent system of education.

I earned a certificate to teach English and, at the same time, a master’s degree in English education with an emphasis on the teaching of writing, this because I had come to find writing to be a way into self for the purpose of clarification of individual worth and value in society, a means for exploring the kind of thought of which one was capable of if he or she allowed him or herself to go deep in to understand the reality that existed around and beyond—possibilities. I took the degree and the certificate, and I left Humboldt State University with a strong sense that I could and ought to change things so that those in the schools could receive an education that would allow them to grow up as themselves to know ←2 | 3→themselves as meaningful in the universe and with power to shape society at least as much as it shaped them. I took a job as an English teacher at Glide High School in Glide, Oregon, a very small town in the hills above Roseburg, a town in the woods where for generations its citizens made their livings as lumberjacks and workers in the mills nearby. I took the job because I was sold on the setting, in the western Cascades at a place where the Umpqua River and the Little Umpqua River crashed wildly into one another. The spot is aptly named Colliding Rivers, and it is spectacular to see and hear.

The school is on the river, but feet from that magnificent spot, a school situated in a setting of natural beauty but, at the time I was there, serving a community in considerable stress. The timber industry was in rapid decline, and good numbers of people who live in Glide and the surrounding hills were either out of work or on notice that they might soon be out of work. It was a place filled with fear and resentment, the fear reasonable, the resentment somewhat misdirected to blame those trying to save what was left of the forests instead of the huge lumber companies that had greedily cut as quickly as possible without concern for the demise of the forest. Even without the rules government was beginning to impose, the end of the logging industry as a bonanza business for the lumber corporations and a provider of living-wage work for residents was eminent. The near future hung over Glide parents and Glide students as a dark cloud that no one could escape from being under. There was a monumental transition taking place there, and the students, sons and daughters of lumberjacks and millworkers, were coming to realize that their futures would not be what they had always expected they would be. Few who lived in Glide and around Glide—some students spent hours on busses to attend, the Glide school district being, geographically, the largest in the country—because of their histories, took seriously what the school had to teach, not very important to the lives they had lived, were living, or expecting to live.

There was effort spent at Glide High School to impress upon students and parents the idea that school was more essential than ever in a place where few had ever seen school to be worthwhile at all. What was being taught at the school was not much different than what it was two or three generations back, and most everyone in the community experienced school as something to be endured because the state penalized non-attendance. Basketball and football made the school relevant to many, but the relevance of sport did not help to make work in the classroom meaningful to the citizens of Glide. Teachers at Glide were told by the principal to teach as the school board demanded, the board of Glide citizens working to satisfy, as they understood them, the state’s requirements upon which ←3 | 4→funding was contingent. Teachers worked for a board of citizens who had, most of them, endured mandated education without developing anything that could be called affection for school learning. They served, too often, to keep down costs and make sure that nothing they considered to be too radical would be taught in the classrooms for which they paid. They did believe that certain ideas were dangerous and that certain others were so righteous as to be acceptable, without a doubt.

I taught English and was told to do so carefully. English was a subject that, more so than math or home economics, was understood to have the potential to introduce suspect ideas. Science, at the time, was another because it was known to most in the region that it was being used to support initiatives that were or could affect life in Glide in unpleasant ways, politically and religiously. Those teaching in the controversial disciplines knew well of the sentiment and were warned regularly by the administration to avoid the kinds of controversies that the board and community communicated loudly were to be avoided. The community-friendly approach took the heat out of the curriculum and enforced a dullness that made excusable students’ lack of engagement with what was going on in their classrooms and an unwillingness to spend time outside of school doing the work assigned them. The state curriculum, always designed to be teachable using the commercial texts, was, for the most part, safe enough to satisfy most communities and, therefore, dull enough to deny students across the state any kind of deeply relevant and exciting learning experience.

Most of my students did not like English. Students coming to me from the junior high school knew from the first day that they would have to find ways to survive the boredom they expected to experience during the fifty minutes each school day they would have to be with me. They knew this before they met me, and a good part of the work I would have to do would be to convince them there was reason to stay awake and pay attention. It was no easy task, in part because so many did not want to be convinced, they having spent years finding more or less effective ways to cope with what years of school had led them to expect. They had taken a lot of English during their time in school, and much of what they did not like about the English they had been taught, I did not like either. “Good grammar,” for example, they felt, was of no use to them and in terms of the reality they knew, and they were right to think that grammar, as mandated by the curriculum, did them no good in the immediate as they were experiencing it. There was no convincing them that speaking or writing grammatically would help them in the world beyond Glide when they had hardly any familiarity with that world. That sanctioned proper language, they knew, was not the Glide standard. ←4 | 5→They could talk to and be heard, they could understand and be understood by those who mattered in their lives, and none of what was being taught to facilitate the growth of language skills had anything to do in their lives with using language better and more effectively.

They struggled and I struggled. Shakespeare was mandatory, of course; the words of the Bard are absolutely meaningless unless one is willing to do the work necessary to understand them. My students had nothing they could come close to liking in the content, works of Shakespeare, taught to them; no matter how hard I tried to help them develop it, no matter what devices I employed to make Shakespeare relevant. I knew the tricks published with great frequency in the English journals, tricks created in such abundance because of the problems most English teachers knew Shakespeare to present, of how to make it interesting enough for students to engage in a very difficult process of interpreting archaic language by helping them to understand the value of stories that were, to them, considerably less compelling than the stories available everywhere around them, told in language they already understood. My students insisted on being their stubborn selves, willing only to do the work if the work was meaningful to them, not in the abstract for an abstract future, but in and for the here and now. They had little use for what seemed to them, and often to me, sappy moralistic textbook stories. I knew of better works, better at getting at the same or better morals, but was prohibited from sharing them. They lived in Glide, Oregon where Ken Kesey could not be taught! They could be assigned Emerson and Thoreau but never poems with such lines as

I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness, starving, hysterical, naked,

dragging themselves through the negro streets at dawn looking for an angry fix,

angelheaded hipsters burning for the ancient heavenly connection to the starry dynamo in the machinery of night,

who poverty and tatters and hollow-eyed and high sat up smoking in the supernatural darkness of cold-water flats floating across the tops of cities contemplating jazz.

Ginsberg was not exactly their lives, but their lives enough, enough that I could help them see relevance in the most detested literary form—poetry. With a few hard-hitting writers, I could have shown them the real power of poetry and prose to convey deep and powerful feelings to make them meaningful to others, their poverty and pain experienced by others elsewhere in many different forms.

←5 | 6→I did reach some of my students, sometimes, but not often enough to feel that I had succeeded with them or for them. I took chances, tried to reason with administration and sometimes with their parents. I did bring in unsavory literature that some came to savor, and I pointed many to books and newspapers and films and such that they could access if they wanted to on their own. Some came back with stories, their own and found ones, that were told in class for the sake of showing what they thought to be good stories, stories they wanted to tell or have told but had never been made comfortable enough in school to tell them, stories they understood to be of a kind not acceptable for telling in school. Stories of their own experiences and of their own imaginations they understood would get them in trouble for the telling.

I have asked myself continuously, or at least time and again, throughout my educator’s career, what I could have done differently and understood then and henceforth that much of what I could have done and should have done would have gotten me fired.

I needed to think about the problem that was mine as a teacher and for those I taught, and I couldn’t do this at Glide. I quit and enrolled at University of Oregon doctoral program in education. I wasn’t there primarily to become a professor. I wanted to study the problem and find a way to do what was necessary to make school good for all students, good enough to get them involved deeply enough into the process of becoming educated so that they would understand it well enough to use effectively to get meaning from their experiences in life, those in school included, that would allow them to live better, as well-informed and highly thoughtful human beings. Most of the courses I took at Oregon, those required for the degree, helped a little to answer the questions I needed answered, and some, exhilaratingly, pushed me deeply into theory and philosophy to ground the rest of my life’s work. Chet Bower’s course was one of these, and my reading of his book, The Promise of Theory: Education and the Politics of Cultural Change (Bowers, 1984), was a journey into the kind of thinking I needed to be doing to get where I wanted to be. I also took enlightening courses from Christine Chaille, an early-childhood-education professor who became my doctoral program advisor even thought my stated area of interest was secondary education.

I found through Chaille’s courses, our long conversations, and her books, The Young Child as Scientist and Constructivism Across the Curriculum in Early Childhood Classrooms: Big Ideas as Inspiration, a perspective on education that considered the student to be a whole rather than incomplete person and an approach to research and the development of instructional programs grounded in a profound respect for mindfulness. The cognitive developmentalist educators, ←6 | 7→I found, were motivated in their work by a sincere desire to understand the minds of those who were students. Christine had developed incredible means to tap into children’s thinking by listening intently as they used their own sensibilities to make sense of information coming their way as they experienced the world. She and others of like mind had the patience to hear them out and the desire to speak with them in ways that showed them respect for their thoughts, a sincere desire to learn of them from them.

Dr. Chaille created an early-childhood center where kids played the day away constructively, using their minds to figure out how to get interesting things done by their own means in collaboration with others whose thoughts and actions they came to appreciate and respect because they were useful in getting those interesting things done. As a result, I came to think about secondary education in a very different way. I came to consider how instructional practices in terms of how they would affect how students learned what was taught, but, more importantly, I was keen to study the way students thought, not only about the material being taught but also about how students thought of about themselves as thinkers. I came to understand that those who learned well knew themselves to be good enough thinkers to do what was necessary, thought wise, to learn well. Chaille’s colleague and good friend, Christine Pappas, served too as a mentor, she is the author of the book, An integrated Language Perspective in Elementary School: An Action Approach. She too was directed in her thinking by what she learned from paying attention to children, and the English language arts methods she advocated were very much like those I considered best for older students—student-centered and problem-solving-based methods.

Details

- Pages

- X, 288

- Publication Year

- 2022

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781433189951

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433189968

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781433189975

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433189982

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433189999

- DOI

- 10.3726/b19666

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2022 (October)

- Keywords

- Education philosophies methodologies mind democracy progressivism Progressive Education for Democratic Society Smitty! Not g, Dr. Spearman Stephen Lafer

- Published

- New York, Berlin, Bruxelles, Lausanne, Oxford, 2022. X, 288 pp., 1 b/w ill.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG