Multilingual Education under Scrutiny

A Critical Analysis on CLIL Implementation and Research on a Global Scale

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Dedication

- Foreword

- References

- Acknowledgement

- Multilingual education under scrutiny: A critical analysis on CLIL implementation and research on a global scale

- Table of Contents

- Part I. CLIL as a global trend

- Chapter 1. An international review of multilingual education: CLIL across continents

- 1.1. European CLIL

- 1.2. CLIL beyond the European Union

- 1.3 Influencing factors in CLIL implementation at the international level

- 1.4. The crucible of CLIL

- Bibliography

- Chapter 2. The multiple faces of CLIL

- 2.1. From the theoretical foundations of European CLIL to a multimodal approach

- 2.2. Beyond the 4Cs: Affective factors and attention to diversity in CLIL classrooms

- 2.2.1. Affective factors in CLIL: Authenticity and motivation

- 2.2.2 Attention to diversity in CLIL

- 2.3. CLIL as an ecological phenomenon

- Bibliography

- Part II. Assessing CLIL outcomes: Language and content learning and impact on the mother tongue

- Chapter 3. Empirical studies on the effectiveness of CLIL for language learning

- 3.1. Language learning as the main rationale for CLIL

- 3.2. The debate about the affected and unaffected language competences

- 3.3. CLIL and development of oral skills

- 3.3.1. The case of listening comprehension

- 3.3.2. Oral production as the most evident benefit

- 3.4. Critical views on the contribution of CLIL to language learning

- 3.5. Updated empirical studies on language outcomes and future paths ahead

- Bibliography

- Chapter 4. Content acquisition in CLIL settings: From pedagogical guidelines to empirical outcomes

- 4.1. The role of contents in CLIL

- 4.2. The integrated learning in formal education

- 4.3 Pedagogical frameworks to enhance the integrated learning

- 4.4. Research on content outcomes: Main challenges of the integration under scrutiny

- 4.5. Future lines of study on content learning

- Bibliography

- Chapter 5. Research-based findings on development of the mother tongue in CLIL programmes

- 5.1. Acquisition of literacy in the L1 in immersion programmes: The paradigm of Canada

- 5.2. Lessons learnt from the Canadian immersion experience on mother tongue acquisition

- 5.3. Literacy development in L1 in CLIL: The case of maximal L2 input settings

- 5.4 The case of Spain: Mother tongue and CLIL in bilingual and monolingual settings

- 5.5. Final considerations: Pedagogical guidelines related to the role of languages in CLIL and future lines of work

- Bibliography

- Part III. Preservice and inservice CLIL teacher training

- Chapter 6. Critical analysis of initial teacher education for CLIL

- 6.1. CLIL education at university

- 6.1.1 The repercussions of Bologna on the design of education degrees

- 6.1.2 Postgraduate offer to cater for CLIL education

- 6.2. Meeting the challenges of prospective CLIL teachers: The need for a multivariate analysis

- 6.3 Context analysis of preservice CLIL teacher education in different countries: The case of Spain, USA and Japan

- Bibliography

- Chapter 7. Inservice teacher training: Contentious issues and pending tasks

- 7.1 Conceptualising and defining CLIL teacher training: The “problem” of heterogeneity of profiles and backgrounds

- 7.2 The design of training courses on CLIL: Pre-while-post CLILing

- 7.3 Inservice training initiatives in different contexts

- 7.3.1 Asociación “Enseñanza Bilingüe”, EB Spain

- 7.3.2 National Association for Bilingual Education, NABE

- 7.3.3 Japan CLIL Pedagogy Association, J-CLIL

- Bibliography

Chapter 1. An international review of multilingual education: CLIL across continents

Abstract: The introduction of Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) in European classrooms at the end of the 20th century and its spread beyond its borders in the second decade of the 21st century constitute a complex educational phenomenon that has not been without difficulties, challenges and questions that remain to be answered. Despite its origins, linked to economic, social and linguistic policies envisaged by the European Commission, CLIL has gone beyond the European Union and has made its way into other socio-economic and political scenarios. However, while the US or Canada have the need to develop policies based on the promotion of a multicultural and multilingual education and the European Union pursues the desire to promote the use of multiple languages among their citizens, Asian countries, such as Japan, look at CLIL through pedagogical lens as an alternative to traditional English as a Foreign Language (EFL) methods (Ikeda et al., 2021). This chapter, firstly, describes the witty strategy led by the European Commission in order to increase the number of foreign languages learnt at European schools and, hence, the number of plurilingual citizens all around the EU. This ambitious policy, supported in part by the CLIL approach, has resulted in the introduction of foreign languages as the languages of instruction in mainstream education in the EU countries. Moreover, in order to grasp worldwide CLIL trends, the chapter analyses different scenarios in which this approach has anchored its theoretical foundations and principles due to its alluring nature likely to cater for the idiosyncrasies of different educational policies and institutional purposes that promote the learning of foreign languages or second and third languages through CLIL. The chapter also offers the contextualisation and analysis of the different factors influencing CLIL implementation in those scenarios. Finally, a comparative study of Spain, Japan and US is conducted to outstand how alike and different these versions of CLIL are.

Keywords: European Union, educational policy, bilingual education, multilingualism, language instruction, foreign languages.

←21 | 22→1.1. European CLIL

Education in Europe has gone through many stages and models. This evolution is especially noteworthy in the teaching and learning of languages. At the end of the 20th century, there was an important change in the educational paradigm, promoted by the European institutions, from a linear educational model, which supported a type of education based on the intellectual culture of the Enlightenment, suitable for the industrial society, to a school capable of facing the challenges of the generation gap opened by the speed of changes in the economic, cultural and personal spheres throughout the world.

The paradigm shift has introduced an education model focused on understanding and attention to contextual and individual differences in substitution of a model focused on standards and objective knowledge of hierarchically organised subjects. This new perspective has also modified the teaching and learning of foreign and second languages, which have undergone an important transformation process. There has been a shift from methods focused almost exclusively on grammar and translation, to more eclectic approaches aimed at developing communicative competence in the second language (van Esch & St John, 2003 cited in Coyle et al., 2010). According to Jacobs and Farrell (2001), these changes in second language education can be summarised in eight: “learner autonomy, cooperative learning, curricular integration, focus on meaning, diversity, thinking skills, alternative assessment and teachers as co-learners” (p. 4). They clearly reflect the transition from positivism to post-positivism and from behaviourism to cognitivism.

However, this constructivist approach to language learning has not been fully installed in the classroom. Sometimes it has been introduced gradually, through small innovations in the school (Casanova, 2009) and, in other cases, indirectly, through the development of educational policies that include a constructivist methodology, as is the case of the Bilingual Programmes and the CLIL approach implemented all over Europe. In this vein, critical voices, such as Dendrinos’, are demanding this new didactic paradigm for language education “in Europe and beyond because in today’s interconnected world, the ability to speak multiple languages and communicate across linguistic devices are critical competences” (p. 9).

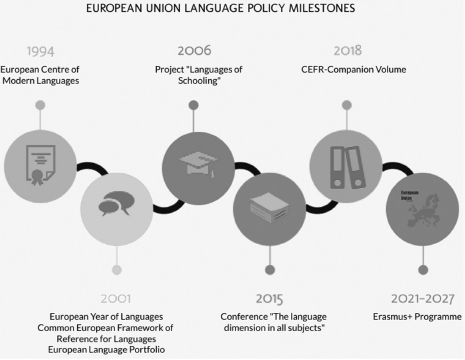

This new paradigm for language education, which is drawn unevenly throughout the European territory (European Commission, 2017; Dendrinos, 2018), not only affects the teaching of second or foreign languages, but it also covers the teaching of the many languages spoken in the continent (European Education and Culture Executive Agency, 2019). Furthermore, this is a change that is happening now (Marsh, 2013). To better understand the interest of the European Union in ←22 | 23→improving language learning methodologies and standards, Fig. 1 shows a selection of milestones of the language policy (1994 to present) in the EU throughout the last decades.

Fig.1: Timeline of the milestones in the language education policy of the EU. Source: own elaboration, based on Council of Europe (2022)

In the course of this educational language policy, the conceptual difference between multilingual, referred to a geographical area, and plurilingual, referred to people, introduced in the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) (Council of Europe, 2001), deserves special attention.

(Plurilingualism is) the ability to use languages for the purposes of communication and to take part in intercultural interaction, where a person, viewed as a social agent, has proficiency of varying degrees, in several languages, and experience of several cultures. This is not seen as the superposition or juxtaposition of distinct competences, but rather as the existence of a complex or even composite competence on which the user may draw. (Council of Europe, 2001, p. 168)

From this definition it is understood that the goal of language learning is not to acquire native-like proficiency but to be competent and be able to communicate and interact in intercultural contexts. Thus, in multilingual areas, some individuals may be monolingual, while others may be plurilingual. That is, the individuals can develop a pluricultural and intercultural competence since they are social agents in a certain context, in which they interact with different languages and cultures from which they create their own meaning. The “CEFR-Companion volume” (Council of Europe, 2018) takes account of this competence and introduces descriptors for mediation and linguistic and non-linguistic resources.

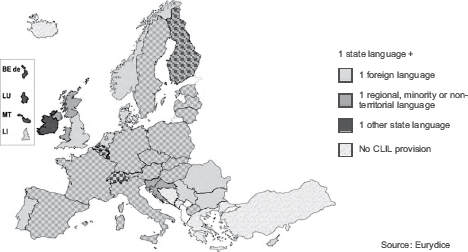

Another important instrument to assist education systems and policies in Europe is Eurydice1, a network of 40 national units based in 37 countries of the Erasmus+ programme2. Its first publication to promote the implementation of CLIL across European schools was “Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) at school in Europe” (European Commission, 2006). Another important publication was the “2017 Edition of Key Data on Teaching Languages at School in Europe”, which pictured the education policies for teaching and learning languages in 42 European education systems (European Commission, 2017). Fig. 2 shows the versatility of the approach to work with different languages in different linguistic contexts.

Fig. 2: Status of target languages taught through CLIL in primary and/or general secondary education (ISCED 1-3), 2015/16. Source: European Commission (2017, p. 56)

←24 | 25→In this context, in which the starting age of the second foreign language has been advanced in a large number of European countries, one of the European Commission’s priorities in linguistic matters is to help these countries to develop new pedagogical tools to guarantee that students have better learning experiences, capable of generating greater linguistic competence when they finish school. To this end, policies to reward innovation in language teaching and learning have been proposed, as well as initiatives to monitor its evolution, in collaboration with the Council of Europe and its European Centre for Modern Languages (ECML)3, an organism launched with the main goal of introducing innovation in language teaching.

Despite the innovative character of CLIL in current education, it is important to remark that using a foreign language for teaching academic content is not new. Bilingual education has a long history, from Ancient Rome, where children were educated in Greek, to the many examples developed in the 20th century in countries where more than one language is spoken such as Luxembourg, Canada, Finland, Ireland or USA (Fernández Fontecha, 2001; Mehisto et al., 2008). Actually, CLIL has been used in border regions and areas in which the multilingual reality has demanded the learning of more than one language (Mehisto et al., 2008) years before the conceptualisation of CLIL. Thereby its novelty lies in its rapid expansion throughout Europe and the implementation and regulation of CLIL in the educational systems of many different EU countries. From the academic point of view, the works by Mohan (1986, 1991), Brinton et al. (1989) or Snow (1990), in bilingual contexts in North America, and Fruhauf et al. (1996) or Marsh and Langé (1999), in non-bilingual contexts in Europe, are clear examples of proposals that introduced the relationship between language and content in the learning of second languages before the conceptualisation and implementation of CLIL by European institutions, among which the ECML has played a key role.

The Council of Europe’s ECML is an instrument to promote collaboration between researchers, experts, teachers and administrations. This centre has been promoting innovative approaches in the field of language teaching since 1995 and helping to develop and disseminate examples of good practice ever since. In the communication entitled “Promoting Language Learning and Linguistic Diversity: An Action Plan 2004-2006”, it is mentioned that “content and language integrated learning (CLIL), whereby students study a subject in a foreign ←25 | 26→language, can contribute considerably to the learning objectives of the Union” (European Commission, 2006, p. 9).

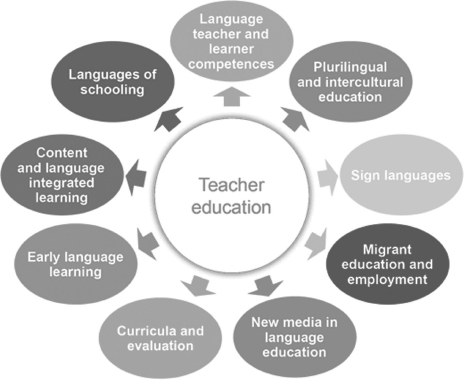

Since then, the ECML has developed numerous actions and activities to promote language education across Europe, which are derived from nine key areas. As can be seen in Fig. 3, CLIL is one important thematic area of the ECML.

Fig. 3: Thematic areas of ECML expertise. Source: Council of Europe (ECML/CELV) (2022). https://www.ecml.at/Thematicareas/Thematicareas-Overview/tabid/1763/language/en-GB/Default.aspx

The future of language education in Europe is clearly oriented to keep on fostering the potential linguistic diversity of the EU and promoting the development of multilingual competences (European Commission, 2020). The EU Council Recommendation on a comprehensive approach to the teaching and learning of languages (adopted in May 2019) constitutes the framework for the development of innovative policies and practices in language teaching, among which CLIL is key to an effective application of an inclusive perspective of all ←26 | 27→languages both in education and in society. The recent publication “The future of language education in Europe: case studies of innovative practices” (European Commission, 2020) explores emerging innovative approaches and strategies of language teaching in Europe supporting learners’ plurilingualism and points out eight projects and tools from the Council of Europe’s ECML, which are focused on promoting plurilingual pedagogies:

Details

- Pages

- 138

- Publication Year

- 2022

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9783631883617

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9783631883624

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9783631873229

- DOI

- 10.3726/b20079

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2022 (July)

- Published

- Berlin, Bern, Bruxelles, New York, Oxford, Warszawa, Wien, 2022. 138 pp., 15 fig. b/w, 7 tables.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG