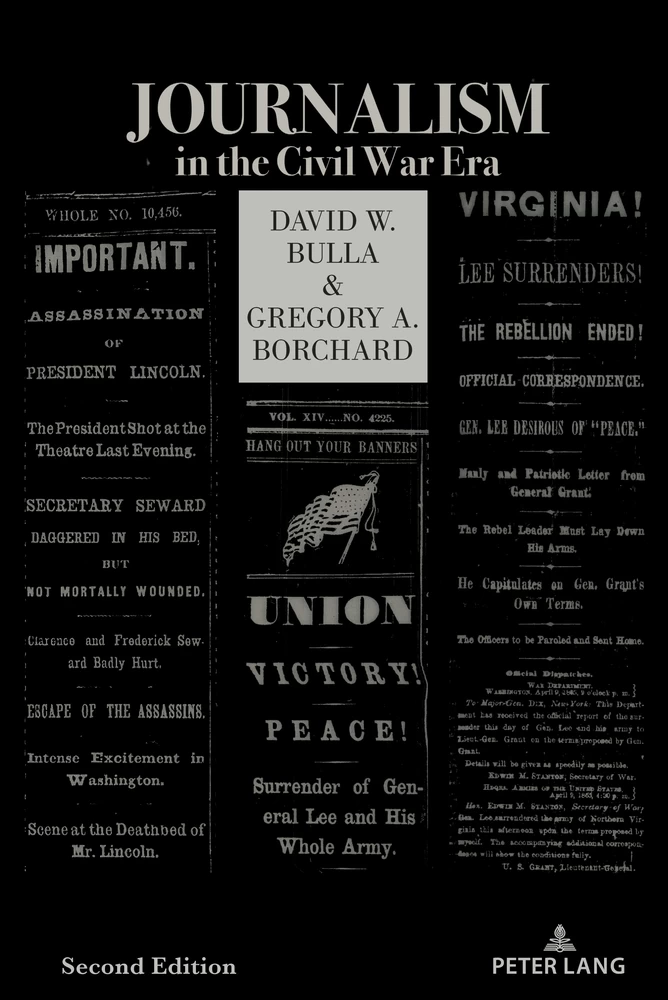

Journalism in the Civil War Era (Second Edition)

Summary

It provides:

An in-depth look at the political press in the 1850s and 1860s, and how it played a major role in the nation’s understanding of the conflict;

Technology’s role in carrying information in a timely fashion;

The development of journalism as a profession;

The international context of Civil War journalism;

The leadership journalists displayed, including Horace Greeley and his New York Tribune bully pulpit;

The nature of journalism during the war;

The way freedom of the press was advanced by polarizing political extremes.

The work is historical, written in an engaging style, and meant to encourage readers to explore and analyze the value of freedom of the press during that very time when it most comes under fire—wartime.

“David W. Bulla and Gregory A. Borchard explore ties between journalism and politics and between New York and the Midwest (then known as the West) before the Civil War. Newspapers shared an increasing emphasis on information over opinion. Facts often tended to fit the editors’ agendas with winners overplaying their triumphs and losers becoming more restrained. Major newspapers, particularly the New York Herald with the largest investment in correspondents, placed news on the front page and interpretation inside, even while publisher James Gordon Bennett initially blamed Lincoln for the war. Major dailies increasingly reported news from the front and smaller papers relied more on opinion and local angles.”—William E. Huntzicker, Minneapolis writer and author of The Popular Press 1833-1865

"Bulla and Borchard have produced what has been long needed in the study of U.S. Civil War journalism: a social and cultural history of the American press that goes beyond anecdotal accounts of war news. They explore the nature of the Civil War-era press itself in all its strengths and weaknesses, ranging from political and economic grandstanding and over-the-top verbal grandiloquence to the sheer bravery and determination of a number of editors, publishers, and journalists who viewed their tasks as interpreters and informers of the day’s news. Using a mix of carefully selected case studies as well as an extensive study of newspapers both large and small, this highly readable work places the Civil War press squarely where it belongs—as a part of the larger social and cultural experience of mid-nineteenth century America."—Mary M. Cronin, Department of Journalism, New Mexico State University

"The study of Civil War journalism has traditionally been treated as a facet of the history of war correspondence, but war reporting does not exist in a vacuum, as David Bulla and Gregory Borchard skillfully show readers in their latest edition of Journalism in the Civil War Era. This new edition freshens the book’s original version by expanding on their insightful examination of the way the American Civil War ushered in the greater reliance on the information model of journalism, which would exist side-by-side with the existing partisan model. Few scholars have attempted the sort of holistic study that examines not only the nature of Civil War journalism but, more significantly, the symbiotic relationship between the press and its culture. Bulla and Borchard have done the hard work of digging out the necessary evidence to paint a full-color portrait of journalism during America’s bloodiest conflict."—Debbie van Tuyll, Professor Emerita, Department of Communications, Augusta University

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the author

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1 A Typical Newspaper of the Era: The St. Joseph Valley Register

- 2 Journalism and Politics: New York and the 1860 Election

- 3 Horace Greeley’s New York Tribune

- 4 News Spin: Fredericksburg, Stones River, and Chancellorsville

- 5 Journalistic Practice and Technological Change

- 6 A Battle of Content: Party Press vs. Informative Press

- 7 Classifieds of the Era: The Case of Ads about Runaway Slaves

- 8 Abolitionism and the Fight to End Slavery

- 9 Beyond the War: Everyday News in Wartime

- 10 The Naval War Mediated in Newspapers and Magazines

- 11 Press Suppression, North and South

- 12 Three Newspapers that Supported the President

- 13 The International Dimension of Civil War Journalism

- 14 Abraham Lincoln’s Legacy Emergent

- 15 Reconstruction Journalism: Two Examples

- Conclusion: Renewing the History of Journalism in the Civil War Era

- Appendix: Journalism and Abraham Lincoln

- Selected Bibliography

- Index

- About the Authors

Illustrations

Image I.1 Statues and Sculpture. Robert E. Lee in Statuary Hall

Image 1.1 Carte d’visite: Schuyler Colfax, 1823–1885

Image 2.1 “The Impending Crisis”— or Caught in the Act

Image 3.1 Horace Greeley statue, Tribune Office

Image 4.1 Virginia. Newspaper Vendor and Cart in Camp

Image 5.1 Rebel Telegraph Operator near Egypt, on the Mississippi Central R.R.

Image 5.2 How Illustrated Newspapers are Made

Image 5.4 Hon. Abraham Lincoln, Born in Kentucky, February 12, 1809

Image 5.5 Reading the War News in Broadway, New York

Image 5.6 A Burial Party on the Battle- field of Cold Harbor, April 1, 1865

←ix | x→Image 5.7 Gettysburg, Pa. Alfred R. Waud, Artist of Harper’s Weekly, Sketching on Battlefield

Image 6.1 New York Tribune, April 4, 1865, front page

Image 8.1 Slave Market of America

Image 8.2 The Hurly- Burly Pot

Image 10.1 The Blockade of Charleston

Image 10.2 The Expedition to Beaufort— Before the Attack

Image 10.3 Submarine Infernal Machine Intended to Destroy the “Minnesota”

Image 11.1 The Copperhead Plan for Subjugating the South

Image 12.1 Our Political Snake- Charmer

Image 13.1 The Right Hon. W. E. Gladstone and the Right Hon. Benjamin Disraeli

Image 15.1 Gen. Grant and Li Hung Chang, Viceroy of China

Image 15.2 Chas. Banks’ Original Spectacular Burlesque

Image C.1 Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, Gettysburg

Image C.2 Dedication Ceremonies at the Soldiers’ National Cemetery, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania

Foreword

By Harold Holzer

Like many American Presidents before and after the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln never shied away from complaining about alleged press abuse—what he called “gas from newspaper establishments.”1 Once, a White House visitor asked Lincoln if he believed the press was reporting on his Administration fairly and accurately. Here was an irresistible chance for the President to vent. He had only recently been subjected to the latest round of what an admirer called “violent criticism, attacks, and denunciations” from both “radicals” and “conservatives,” and Lincoln was no doubt chafing over the opprobrium.2

According to one account of this incident (as spun by White House artist-in-residence Francis B. Carpenter), the President considered the question for only a few seconds before he was characteristically “reminded of a little story.” It seemed that a pair of immigrants “fresh from the Emerald Isle” was traveling West when, one evening, the men were loudly greeted by “a grand chorus of bullfrogs”—a cacophony they had never heard before. Unable to discover the source of the deafening “B-a-u-m!—B-a-u-m!,” one frightened Irishman turned to the other and whispered: “And sure … it is my opinion it’s nothing but a ‘noise!’” As far as Lincoln was concerned, Carpenter insisted, loud criticism was nothing but “noise.” Rebukes “rarely ruffled the President.”3

←xi | xii→And yet his Administration—the Union army—and in at least one documented case, Lincoln himself—censored and shut down more newspapers, and arrested and imprisoned editors more often, and in greater numbers, than any other civilian or military authority in the nation’s history. In personally acting against the New York World and New York Journal of Commerce on May 18, 1864, Lincoln deployed unusually harsh language in commanding the army to “take possession by force, of the printing establishments … prevent any further publication therefrom,” and to arrest the offending editors “until they can be brought to trial before a military commission.” According to Lincoln’s order, the two papers had “wickedly and traitorously” printed a “false and spurious” presidential proclamation “to give aid and comfort to the enemies of the United States, and to the rebels now at war against the government.”4 In truth, the fake proclamation did no such thing; Lincoln and his Secretary of War, Edwin M. Stanton, clearly overreacted, deeply worried that the Administration’s true, secret conscription plans had been leaked to the press. Sometimes, gas and noise proved impossible to ignore.

Here is the enduring anomaly that scholars of Lincoln and the Civil War press have explored in earnest for some four score years—a question repeatedly asked, but never fully answered, by biographers, historians, and political scientists. Why did a war that generated more press coverage, wider readership, and greater journalistic opportunity, than any event to date also ignite the most widespread censorship and suppression? Was Lincoln, the savior of the Union, also the enemy of a free press—indeed, guilty of the very tyranny of which many Democratic editors accused him at their peril?

The response is usually straightforward: partisanship transformed the press into enemies of the people. Observers have convincingly demonstrated that the Civil War era press largely covered the war and the White House through the lens of politics, for newspapers of the era were deeply enmeshed in political organizations, Democratic and Republican. Many editors served as politicians, and many politicians as editors. Several members of Lincoln’s initial Cabinet had run newspapers, including Simon Cameron and Gideon Welles. Lincoln’s crackdowns targeted only Copperhead journalists, and were often applauded by pro-war, anti-slavery Republican editors.

But as this new book shows, the story is far more complicated. Politics was only one of the factors animating wartime newspaper coverage. To those who think the press differed only politically, or by region—North and South—this study will come as a revelation. It explores both small-town and big-city papers, civilian and military publications, and not only the unsurprising difference in ←xii | xiii→coverage in the North and South, but unanticipated differences East and West. It addresses the influence of personal, if sometimes pseudonymous journalism, and probes the power of advertising to encourage positive policy change, or in the case of slave-auction and runaway-slave ads, to perpetuate policy of the inhumane variety.

The book also explores the technological changes that brought news to Americans more rapidly, and more widely, than ever before—inviting closer scrutiny and greater suspicion, just as social media does today—and it weighs the perennial dilemma facing journalists torn between partisan loyalty and editorial integrity. Here, too, are reminders that readers of the day did not consume only war news and political coverage; they were also treated to both hyper-local and international stories, to woodcut illustrations and, eventually, photographs, and to reports on business, culture, and even the weather.

Of course, the focus on these pages inevitably returns to military and political coverage, and how it impacted the rise of Lincoln and the preservation of the Union, even when it meant covering up the most disastrous federal battlefield defeats. Whether or not it answers the lingering questions about the President’s tough stance against editors who went beyond criticism and, in his view, flirted with treason, remains open to debate. At the very least, the book helps us understand how a man lionized after his death as a savior and liberator could present himself during his presidency as both a St. Sebastian enduring slings and arrows, and a Torquemada who willingly assumed the role of grand inquisitor. Perhaps it should never be forgotten that Lincoln once revealingly blurted out to Lawrence Gobright of the Associated Press: “I have always found what I say to be true.”5

On another memorable occasion, resulting in a slightly different version of the Irish “noise” story, Lincoln was—again—asked how he felt about yet one more denunciatory volley by the press. His response did little to solve the mystery of the Janus-like nature of the Civil War President’s attitude toward coverage and criticism, or narrow the reputational chasm between his images as tolerant forgiver and the relentless censor.

“That reminds me,” Lincoln replied, “of a farmer who lost his way on the Western frontier. Night came on, and the embarrassments of his position were increased by a furious tempest which suddenly burst upon him. To add to his discomfort, his horse had given out, leaving him exposed to all the angers of the pitiless storm.

“The peals of thunder were terrific, the frequent flashes of lightning affording his only guide on the road as he resolutely trudged onward, leading his jaded ←xiii | xiv→steed. The earth seemed fairly to tremble beneath him in the war of elements. One bolt threw him suddenly upon his knees.

“Our traveler was not a prayerful man, but finding himself involuntarily brought to an attitude of devotion, he addressed himself to the Throne of Grace in the following prayer for his deliverance:

‘O God! Hear my prayer this time, for Thou knows it is not often that I call upon thee. And, O Lord! If it be all the same to thee, give us a little more light and a little less noise.’

“I wish,” the President concluded sadly, “there was a stronger disposition manifested on the part of our civilian warriors to unite in suppressing the rebellion, and a little less noise as to how and by whom the chief executive office shall be administered.”6

Yet despite the presidential complaints and crackdowns, the “noise”—the unrelenting, occasionally unsettling, reports from the era’s “civilian warriors”—never abated. At least this book sheds “a little more light” on the story.

Notes

1 Michael Burlingame and John R. Turner Ettlinger, eds., Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1997), 188 (entry for April 24, 1864).

2 Francis B. Carpenter, Six Months at the White House: The Story of a Picture (New York: Hurd & Houghton, 1866), 154.

3 Ibid, 155.

4 Lincoln to General John Adams Dix, May 18, 1864, in Roy P. Basler, ed., The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, 8 vols. (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1953-55), 7:345-46.

5 L. A. Gobright, Recollections of Men and Things at Washington During the Third of a Century (Philadelphia: Claxton, Remsen, & Haffelfinger, 1869), 337, 338. Lincoln made the remark after complaining about unauthorized, premature press reports.

6 Alexander K. McClure, “Abe” Lincoln’s Yarns and Stories: A Complete Collection of the Funny and Witty Anecdotes that Made Lincoln Famous as America’s Greatest Story-Teller (New York: Henry Neil, 1901), 80.

Preface

The Times that Were

“The illusion that the times that were are better than those that are, has probably pervaded all ages.” Horace Greeley, The American Conflict, Vol. 1 (New York, Chicago, Hartford: O. D. Case, 1866), 21.

This second edition of Journalism in the Civil War Era revisits areas explored in the first edition (Peter Lang, 2010) by re-examining the contributions of newspapers and magazines to the American public’s understanding of the nation’s greatest internal conflict. Both editions document the effect the Civil War had on journalism and the effect journalism had on the Civil War. Journalism in the Civil War Era describes the politics that affected the press, the constraints placed upon journalism, and the influence of technology on communications. It profiles the editors and reporters who covered the war and examines typical newspapers of the era, while providing a broad account of journalism in the mid-nineteenth century. The authors, David W. Bulla and Gregory A. Borchard, wrote this book intending it as an important reference for scholars and students, as well as a supplementary text for courses in journalism history, U.S. press history, civil rights law, and nineteenth-century history.

←xv | xvi→The second edition of Journalism in the Civil War Era expands on topics from the first edition by adding perspective on particular issues that are in need of updating since its original publication. This edition does this, first, by broadening the scope of the initial text to look at international coverage of Civil War issues and post-war issues facing the press, and adds chapters centered on abolitionism in the press, naval battles, and the role of classified ads during the era. Further, it expands on analyses of Abraham Lincoln’s legacy, with the press’s coverage of his assassination as a starting point.

This edition continues to provide a broad account of journalism during the Civil War, reflecting on the political, military, legal, and journalistic issues of the era. Its chapters examine these various facets of the journalism of the period, and the theme of the development of the wartime press emphasizes the professional, political, social, economic, legal, and military factors that affected it. It began as academic conversations between the authors when they were doctoral students at the University of Florida almost twenty years ago. More specifically, the authors began making presentations on their findings in the late 1990s at the University of Tennessee, Chattanooga’s Symposium on the 19th Century Press, the Civil War, and Free Expression, and discovered a like-minded interest in exploring underdeveloped areas of press and Civil War-era scholarship. At least in part, Peter Lang published these conversations in 2010’s first edition of this book. Since then, the authors have maintained their scholarship on the subject. (You now will see a recently reissued 2015 book by Borchard and Bulla, Lincoln Mediated: The President and the Press through Nineteenth Century Media, referenced throughout Journalism in the Civil War Era.) Dialogue between the authors will no doubt continue well after publication of this second edition of Journalism in the Civil War Era.

Given the durability and popularity of the Civil War as a subject among amateur and professional historians, this book again targets a wide audience. What makes this particular endeavor unique stems from the time in which the authors produced it—one in which the press as we know it has changed in ways more dramatic than those of any other era. Historians have documented how, in the years leading to the Civil War, an explosion of technological innovation contributed to the democratization of the press—comparable in some respects to the era in which we now live. Yet, as traditional members of the press wait to see if newspapers will continue to exist in a context of predominantly digital media, historians (ourselves included) continue to reconstruct the past based on our best sources—in this case, the leading newspapers of the Civil War. This re-issue of Journalism in the Civil War Era accordingly comes at a critical time: a period in ←xvi | xvii→which historians and citizens alike are reinterpreting the value of the printed word in contributing to social discourse and maintaining the foundation necessary for a functioning representative democracy.

Remarkably, a very real and recent calamity has also befallen the nation in the form of a pandemic, making our current situation in history compounded by changes in the press and acute questions about mortality. According to the August 2021 issue of Time magazine, the United States passed a landmark in the fight against COVID-19 when the death toll surpassed 620,000 people—a figure traditionally cited as the number of deaths during the Civil War. “The grim comparison is telling, not only because of the sheer size of the death toll, but also because it carries a bleak secondary meaning,” writes Rachel Lance, a Ph.D.in biomedical engineering.

The Civil War, infamous for having the highest American death toll of any war in history, was the last major American conflict before the greater public understood how diseases spread. It was therefore the last war where the bulk of the deaths—two-thirds, in fact—were not from bullets and bombs, but from viruses, parasites and bacteria. Unfortunately, today’s COVID-19 death toll shows that many have approached the virus with a medical attitude hardly updated from 160 years ago.1

While a study of the role of the press in covering the recent pandemic certainly merits a different text altogether, recurring contemporary reports of widespread death tolls rivaling those of the Civil War provide context on the press in covering catastrophic events.

Social upheaval accompanying recent events has also revealed the ways in which our contemporary understanding of the past hardly matches the perspectives of previous generations—from those during and immediately after the Civil War through today. Confederate General Robert E. Lee, for example—long considered an icon among those who insist the Civil War was about something other than slavery—has assumed a new role among historians who have reevaluated his legacy vis-à-vis contemporary social justice movements.

Veneration of Lee—along with almost every Confederate (and sometimes non-Confederate) personality from the era—is no longer taken for granted, as identity-conscious activists have increasingly targeted memorials as relics from a past that should be shunned.2

Regarding the roles and perspectives of this book’s authors, some have stayed the same and others have changed since publication of the first edition. On a personal level, Bulla has roots in a Southern tradition and Borchard in a Northern ←xvii | xviii→one. Our different backgrounds, we believe, continue to contribute to a nuanced interpretation of the press and of the war’s participants. Bulla’s scholarship has focused more intensely on the issues of slavery and abolition, as well as international journalism, while Borchard’s work has tended toward editing books and articles on the history of journalism in general.

Image I.1 “Statues and Sculpture. Robert E. Lee in Statuary Hall.” United States Capitol, Washington, DC. Theodor Horydczak, photographer, 1951.3

Interpreting historical materials discovered since 2010 relied on the same method used in the first edition: analyzing primary sources such as personal letters, editorial musings, books, newspaper articles, and historical artifacts. We found these materials in a number of locations, including archival searches of libraries, at museums and historical societies, in online searches, and in some cases, through the exhausting but satisfying process of transcribing microfilm. The scope of sources generally ranges from the Penny Press Era (1830s) to Reconstruction (1870s), and the items featured bore directly on the major themes of this book, including the era’s cultural, economic, institutional, political, and technological issues.

←xviii | xix→The picture of the press during the Civil War that readers will discover is one of a group of participants who played a role in reshaping a nation—a nation that had come into existence only a few generations before. The war was a Second Revolution, in both political and professional senses, as technological innovations of the time facilitated faster and more-efficient means of newspaper production. This revolution in the production of news turned the penny press on its head, as the largest daily publications became complex institutions that made fewer demands of actual labor from leading editors and publishers. As a result, well into the twentieth century advertising agents replaced functions formerly reserved for editors.

This book contributes to literature on the subject by including analyses based (in terms of historiography) in cultural and developmental perspectives; that is, our interpretations analyze the roles of both society and technology in shaping events.4 It features an examination of a typical newspaper—not just the popular urban penny papers, but a small-town newspaper in the Midwest. At the same time, it revisits the contributions of leading editors and publishers, such as Horace Greeley, editor of The New York Tribune, who used his newspaper as a way to advance press freedoms under unprecedented circumstances. The book describes journalism as a specialized profession by including an analysis of technology’s role in carrying timely information to a national audience. It features the beginnings of visual representations of war via Mathew Brady’s photographic exhibitions, and explains the development of journalistic conventions such as the inverted pyramid and the use of graphics (particularly maps). It describes the role of press organizations, including the Associated Press, in diffusing war information and the reaction of readers to major policy issues—including emancipation, taxation, conscription, and suspension of the writ of habeas corpus. In short, Journalism in the Civil War Era synthesizes work on individual subjects—both those that have been examined to some extent in secondary literature and those that have not—along with unexplored primary sources to form new interpretations of issues that have often gone missing in other accounts of the press and the war.

Although countless scholars have addressed either the press or politics during the nineteenth century, fewer have played a particularly direct role in shaping our interpretation of the interconnection of the two during the Civil War. For example, one of the leading works on the press during the Civil War, Robert S. Harper’s Lincoln and the Press (1951), looks at both the pro- and anti-war press; however, written more than half a century ago, it focuses on Lincoln’s political relationship with the press, not on the relationship between the press and society. ←xix | xx→In some respects, a comparable, more-recent book, The Civil War and the Press by David Sachsman, S. Kitrell Rushing, and Debra Reddin van Tuyll (1999), although exceptional in individual contributions, touches on issues explored in this book but lacks a cultural or developmental theme.5

Books offering general treatments of journalism during the Civil War have tended, meanwhile, to focus only on the contributions of individual editors. While Bohemian Brigade by Louis M. Starr (1954) and The Greenwood Library of American War Reporting by Amy Reynolds and Debra Reddin van Tuyll (2005) both provide extraordinary analyses of Civil War reporting, they focus more on issues of press freedoms than on the technological or developmental aspects of journalism. Among sources by writers with a professional journalism background, James Moorhead Perry’s A Bohemian Brigade: The Civil War Correspondents, Mostly Rough, Sometimes Ready (2000) provides a colorful account of the subject but does not explore the social context examined in our book.6 Topical studies, while useful for interpreting specific subjects, also rarely fully explore the larger cultural or developmental arcs in which their topics played a role. For example, Editors Make War, by Donald E. Reynolds (1971), looks at Confederate editors who pushed the war in the South without wholly contrasting them with their counterparts in the North. Fanatics and Fire-Eaters by Lorman A. Ratner and Dwight L. Teeter (2003), another example, examines specific events—six key developments leading up to the war—and how the nation’s newspapers covered them, but its timeline ends with the hostilities at Fort Sumter.

While dozens of other compelling books could be added to this list, Hated Ideas and the American Civil War (2008) by Hazel Dicken-Garcia and Giovanna Dell’Orto in particular shows how newspapers from a wide spectrum of political perspectives framed the most controversial issues of the war. Examining in detail free-speech issues, their book lays a foundation for additional work on the role and evolution of the First Amendment, as described in Bulla’s work on Lincoln’s suppression of the press and Borchard’s analysis of the president’s sometimes-contentious relationship with Horace Greeley of The New York Tribune.7

Indeed, press historians who read our story critically will note the recurrence of The New York Tribune as a primary source. We have also cited scores of newspapers from the era, not the least of them the industry-leading New York Herald, but the fact that Greeley’s Tribune plays a major role deserves explanation.8 Historians interested primarily in the developmental aspects of the American press might rightfully point to James Gordon Bennett’s Herald as among the most influential newspapers of era—outselling its competitors and devoting its vast resources to covering the war in an unparalleled manner.9 However, the ←xx | xxi→Tribune, for our purposes, described the events of the era in more clearly intellectual terms, illustrating a cultural transformation beyond business sales alone. (It is worth noting that Edwin Emery, an honored media historian, observed that while few nineteenth-century figures come close to Lincoln in being the subject of historical studies, Greeley is among that small number).10

While the preceding secondary sources all played roles in interpreting the primary sources of our first edition, scholars have published numerous books on the subject since 2010. The following list is a sample of remarkable titles by year with publishers:

• Patricia G. McNeely, Debra Reddin van Tuyll, and Henry L. Schulte, Knights of the Quill: Confederate Correspondents and their Civil War Reporting, Purdue University Press, 2010.

• Gregory A. Borchard, Abraham Lincoln and Horace Greeley, Southern Illinois University Press, 2011.

• Ford Risley, Civil War Journalism, Praeger, 2012.

• Debra Reddin van Tuyll, The Confederate Press in the Crucible of the American Civil War, Peter Lang, 2013.

• Harold Holzer, Lincoln and the Power of the Press: The War for Public Opinion, Simon and Schuster, 2014.

• Gregory A. Borchard and David W. Bulla, Lincoln Mediated: The President and the Press through Nineteenth Century Media, Transaction, 2015; Routledge, 2020.

Details

- Pages

- XXVI, 436

- Publication Year

- 2023

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433187216

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781433187223

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433187230

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781433187247

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433197932

- DOI

- 10.3726/b18269

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2023 (February)

- Keywords

- personal journalism nineteenth century emancipation journalism history First Amendment censorship Civil War Confederate photojournalis Fredericksburg Gettysburg history illustrated press journalism newspaper Abraham Lincoln media newspapers partisanship press telegraph war photography Journalism in the Civil War Era (second edition) David W. Bulla Gregory A. Borchard

- Published

- New York, Bern, Berlin, Bruxelles, Oxford, Wien, 2023. XXVI, 436 pp., 32 ill.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG