insecure, Awkward, and #Winning

Intersectionality of Race, Gender, and Sexuality in the Works of Issa Rae

Summary

Excerpt

Table Of Contents

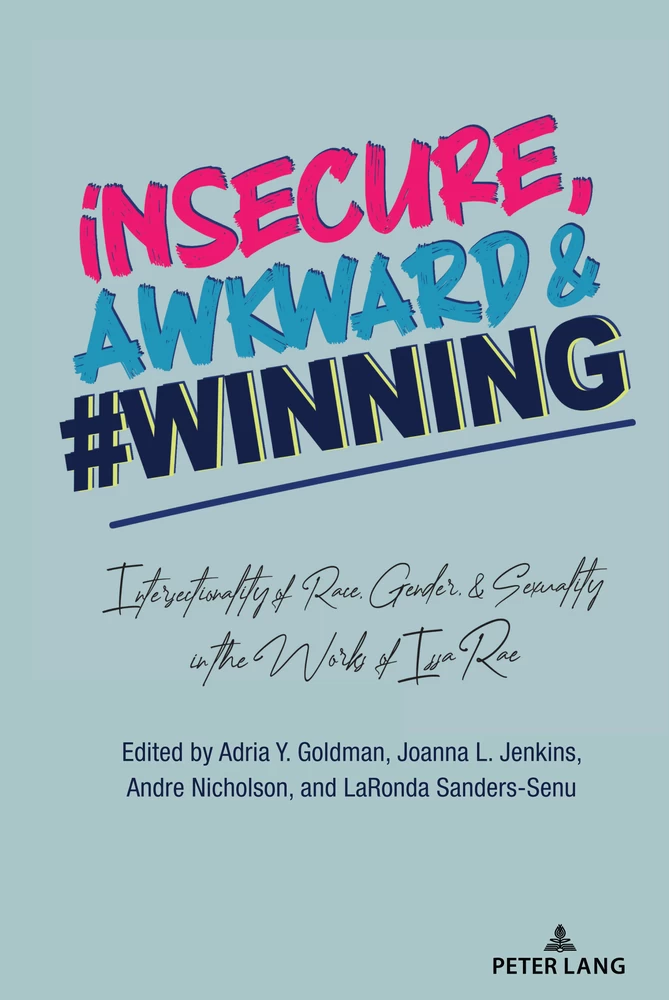

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- About the editors

- About the book

- This eBook can be cited

- Table of Contents

- Introduction (LaRonda Sanders-Senu and Adria Y. Goldman)

- A Critical Perspective on Issa Rae (Clint C. Wilson, II)

- Section I: Hella Intersectional: Gender, Race, and Sexuality

- Chapter One: The Pleasure Principle: Seeking the Erotic in the Works of Toni Morrison and Issa Rae (LaRonda Sanders-Senu)

- Chapter Two: My Ho-tation, My Rules: Discussing New Sex Scripts for Black Women in insecure (Adria Y. Goldman)

- Chapter Three: “Securely” Shifting the Gaze on Black Men (Andre Nicholson)

- Section II: Funny AF?: Humor, Rhetoric, and Identity

- Chapter Four: Hued, Humorous and Human: Interrogating the Rhetorical Significance of the “Awkward” in Issa Rae’s ABG Identity (Ronisha W. Browdy)

- Chapter Five: “Because of Slavery”: insecure’s Due North Narrative and Black Female Agency (Joshua K. Wright)

- A Cultural Studies Perspective on Issa Rae (David Ikard)

- Section III: Lowkey Home: Los Angeles and Gentrification

- Chapter Six: It’s I-Wood Now: An Exploration of Gentrification in insecure (Brittany-Rae Gregory and Sharifa Simon-Roberts)

- Chapter Seven: Hella Black and Hella Proud: How insecure Reshapes the LA Narrative (Christian Dotson-Pierson)

- Section IV: Shady AF: Workplace and the Perils of White Allies

- Chapter Eight: We Got Y’all?: insecure’s Frieda and Issa Rae’s Cautionary Tales about Performative Allies (Emily Ruth Rutter)

- Chapter Nine: White Liberalism and Woke Culture: Storylines in insecure (Christopher K. Jackson)

- Chapter Ten: We Got Y’all: Black Feminism, Misogynoir, and Soul Work in Nonprofits (Vanne-Paige Padgett)

- Section V: Digital-like: Issa and Her Audience

- Chapter Eleven: insecure, Issa Dee, and Facebook: An Analysis of Black Women’s Conversation in Digital Spaces (Morgan W. Smalls)

- Chapter Twelve: Big Complicated: Advertising, Algorithmic Bias and insecure (Joanna L. Jenkins)

- A Multi-Hyphenated Lifestyle Perspective on Issa Rae (Summer Jackson-Cole)

- Final Thoughts: Walking Into the Next Season Like… (Joanna L. Jenkins and Andre Nicholson)

- Appendix A: The Cast of insecure

- Appendix B: insecure Episode Titles by Season

- Contributors

- Series Index

Introduction

How hard is it to portray a three-dimensional woman of color on television or in film? I’m surrounded by them. They’re my friends. I talk to them every day. How come Hollywood won’t acknowledge us? Are we a joke to them?

—Rae (2016, p. 61)

It is a question many people of color may have asked considering the history of mass media and their penchant for stereotypical images, especially for othered identities. As Wilson et al. (2013) explain, media messages (including the use of stereotypes) contribute to the marginalization of certain groups, such as women of color. For Stanford University alumna, Jo-Issa Rae Diop—or as she is creatively known, Issa Rae—the answer to this question is creating her own content that reflects people like her and creating a space for others to do the same. Digital media provide a platform to do so. As Rae (2016) explains in her memoir, The Misadventures of Awkward Black Girl,

online content and new media are changing our communities and changing the demand for and accessibility of that content. The discussion of representation is one that has been repeated over and over again, and the solution has always been that it’s up to us to support, promote, and create the images that we want to see. (p. 62)

Rae speaks from experience, both personal and professional. Growing up in the 1990s, TV representations of Black women such as Synclaire James (Kim ←1 | 2→Coles) from Living Single and Winfred “Freddie” Brookes (Cree Summer) from A Different World helped Rae embrace her own uniqueness and characteristics traditionally deemed undesirable by Eurocentric standards that dominate society (such as her awkward personality and natural hair). These representations were especially helpful when she found herself in predominantly White environments, like school (Rae, 2016). In moments when Rae could not experience Black culture firsthand, mass media served as her teacher. This is consistent with Kellner’s (2003) argument that media serve as a source of cultural pedagogy, teaching its consumers “how to behave and what to think, feel, believe, fear, and desire—and what not to” (p. 9). But overtime, the somewhat relatable and entertaining images Rae loved in the 1990s were outnumbered by what she calls the tragic Black woman—a character who faces a major battle, whether obesity, poverty, her anger, or some other life altering issue (Rae, 2016). Rae was frustrated by the constant use of the tragic Black woman depiction and the fleeting images of the average Black woman. In an interview with NPR, she explains, “We don’t get to just have a show about regular black people being basic” (Deggans, 2016, para. 3).

Creating Her Own Awkward Space

A Home for Issa Dee

Pulling from her own creativity and life experiences, and capitalizing on digital media’s potential, Rae introduced the world to a new type of leading character—one who was more relatable to her own experiences. This new presentation showcased an everyday Black woman and celebrated her averageness and awkwardness. On February 3, 2011, YouTube audiences were introduced to “J,” a Black Millennial woman and protagonist of the web series, The Misadventures of Awkward Black Girl. J is self-described as awkward and uses rap and fantasy moments to deal with certain situations (Ray, 2015). J’s awkwardness is relatable as she faces situations many people experience, but rarely see showcased via mass media. In one episode, J deals with the awkward feeling of passing someone in an otherwise empty hallway, twice in one day, and debating if and how she should greet the person again (Rae, 2011).

Rae explains her motivation behind the series was to create “an extension of my everyday experiences, as well as my friends. I wanted to change the perception and portrayals of black women in television by creating characters and storylines that moved beyond stereotypes and one-dimensionality” (Awkward Black Girl, 2011). The series was such a hit, Rae and her team decided to extend the season from the intended 7 episodes to 12. Although the team worked for free, there were other expenses tied to creating the show, so she called on the fans for financial ←2 | 3→support. On a Kickstarter fundraising page, Rae explains the significance of her web series and the reason for her crowdfunding efforts,

Ever since I launched the show in February, the response has been overwhelming. I’ve received hundreds of letters from fellow “Awkward Girls” all over the world exclaiming how much they relate to the show and the central character’s social struggles as she navigates through life’s many awkward situations. They are relieved to know that they aren’t alone. They’re excited to see a character who represents them. Finally. (Awkward Black Girl, 2011).

Fans answered the call to action, raising well over the $30,000 fundraising goal (Awkward Black Girl, 2011). Production for season 1 of the web series continued past episode 7, and Rae continued to make her mark as a successful and relatable media creator. Christian (2018) explains that a part of Rae’s appeal was her ability to create a community around her web series. Her relatable characters and social media promotions for her web series built a loyal fan base that still feels connected to and represented by her work. Furthermore, the show’s “lead character broke and experimented with stereotypes, while also challenging the industry” (Christian, 2018, p. 124). While hardly her first creative work—having produced various stage productions and videos on Stanford’s campus while pursuing a degree in African-American Studies and a minor in political science—the web series was groundbreaking for Rae’s career and won a Shorty Award in 2012. Even today with Rae’s other projects, The Misadventures of Awkward Black Girl series still garners views and conversations. In August 2020, the premiere episode of the series had over two million views, 30,000 likes, and over 2,000 comments, including some posted in 2020—nine years after the original release. Comments range from longtime fans of the web series praising Rae’s new success to fans of her recent works, curious about where her journey began.

The Appeal of Authentic Awkwardness

Media consumers were not the only audiences noticing Rae’s success, the appeal of awkwardness, and Rae’s formula for successful media content. One interested party was musician, producer and entrepreneur, Pharrell Williams. Williams’s YouTube channel, iamOther, hosted season 2 of The Misadventures of Awkward Black Girl. The web series also caught the attention of networks and production companies, further illustrating the appeal of Rae’s work and the power of digital media in influencing mainstream media’s agenda. Unfortunately, attempts to adapt the web series for prime-time television were unsuccessful as many meetings called for Rae to rework large parts of the show and characters, changing Rae’s vision. One executive suggested she replace “J”—the leading woman with dark skin and short hair—with a character who has light skin and longer hair. Suggested revisions ←3 | 4→such as these only reinforced the stereotypes Rae was hoping to address. Agreeing to these requests would take away from the authenticity and relatability of her works. Closed doors and missed opportunities—including a failed pilot deal with Shonda Rhimes’s production team and ABC—reinforced for Rae the importance of staying true to her vision and desire to present Black women in a new and more relatable light (Wortham, 2015). She would later learn that a premium network would allow her more creative freedom (MSR News Online, 2018).

In February 2013, two years after the premiere of The Misadventures of Awkward Black Girl, the executive vice president of programming at Home Box Office (HBO) reached out to Rae to inquire about ongoing projects. Rae had a new idea—a series about a young woman, heading into her 30s, living in LA, and experiencing life. The main character would be based loosely on Rae’s own personal, social, and professional experiences. Actor and writer, Larry Wilmore, joined Rae in creating a script eventually accepted by the network. In October 2016, the HBO viewing audience was introduced to Issa Dee and Molly Carter, two Black Millennial women navigating life in Los Angeles, including career, love, and friendship (Wortham, 2015). The series continued Rae’s strategic use of rap and fantasy to help tell the stories of Black awkward women and create an empathetic character (Armstrong, 2020).

Rae made history with her series premiere “as the first black woman to create and star in a scripted series for the premium cable channel (she is the second black women to do it in primetime TV, behind Wanda Sykes, who created Wanda At Large for Fox in 2003)” (Deggans, 2016, para. 4). During the same year, Rae released her memoir. Although titled the same as her web series and sharing similar themes, the book takes a different direction, sharing more about Rae’s upbringing, such as growing up as one of five children and living in California, Maryland, and Senegal. Like her web series, both projects proved to be a big success. Her memoir earned a spot on The New York Times Bestsellers List. insecure’s fourth season garnered 4.5 million viewers per episode (Herndon, 2020) and has secured a 5th season. The show also received eight Emmy nominations in 2020 (Television Academy, 2020), although for Rae, awards carry a different meaning: “Awards don’t validate you … They allow more people to know about the series like, ‘Oh, what is this?’ That’s all you want” (Herndon, 2020, para. 5).

A part of Rae’s authenticity is the way her creative works reflect elements of her real life and personality. Even her creative name—Issa Rae—was given to her during a casual conversation with a college friend and serves as Rae’s way of protecting her personal identity and honoring her aunt’s memory. In an interview discussing insecure with HBO, Rae explained, “For my character [Issa Dee], I wanted it to feel close to me because this is a character who is, for the most part, me” (Armstrong, 2020, para. 20). One of the more obvious connections is that the leading character shares Rae’s first name. Issa Dee’s best friend Molly is based ←4 | 5→on Rae’s real best friend who, like the character, is an attorney. Issa works with a nonprofit organization, We Got Y’all, that services Black and Latinx students in Los Angeles, which was also the predominant population of Rae’s high school in Compton. She explains her time in Compton as her “first true immersion in black culture, outside of television” (Rae, 2016, p. 56).

Another part of Rae’s relatability for some may be her membership in the groups she represents. As a Black woman (her father is from Senegal and her mother is from Louisiana) in her 30s (born January 12, 1985) who also spent parts of her upbringing in Los Angeles, Rae presents experiences that she understands—just like J and Issa Dee. For example, in insecure, she shows the LA that ordinary people enjoy. From the luxury of Baldwin Hills to the mom-and-pop eateries of Inglewood, insecure showcases the beauty of places sustained by people of color. As the audience follows the journeys of Issa and Molly, they are comforted by the familiarity of their lives. On the one hand, the show reveals the heterogeneity of African-American communities, and on the other it sparks recognition of cultural hallmarks to which television audiences have not been historically privy.

Others have caught on to Rae’s mass appeal, calling on her to contribute to their projects. Rae is an ambassador for CoverGirl and a voice for Google Assistant. She has also been featured in a number of popular films including The Hate U Give, Love Birds, The Photograph, and Little. In addition, she has been included on Glamour Magazine’s 35 under 35 list and Forbe’s 30 under 30 list. She is building her professional network, continuing to work on large projects and with big names. She is working with Jordan Peele (writer, director, producer, comedian, and actor) on a sci-fi film titled, Sinkhole in addition to her own feature—a crime comedy titled, Perfect Strangers: Badmash. Her production credits include her own works (such as insecure), films in which she was featured (such as The Lovebirds, The Photograph), and other shows that present nontraditional media representations of Black women, such as HBO’s A Black Lady’s Sketch Show. Her more recent executive producer credit is for the upcoming documentary, Seen & Heard. According to HBO the two-part documentary, “explores the history of Black television as seen through the eyes of trailblazers who wrote, produced, created, and starred in groundbreaking series of the past and present” (HBO, 2020, para. 1). Considering Rae’s commitment to new, multidimensional representations of Black women and creating spaces for other marginalized groups, it is exciting to see how her career unfolds and what messages she communicates.

Details

- Pages

- X, 294

- Publication Year

- 2023

- ISBN (Softcover)

- 9781433176685

- ISBN (PDF)

- 9781433176692

- ISBN (ePUB)

- 9781433176708

- ISBN (MOBI)

- 9781433176715

- ISBN (Hardcover)

- 9781433176678

- DOI

- 10.3726/b16447

- Language

- English

- Publication date

- 2023 (February)

- Keywords

- Humor Stereotypes Intersectionality Race Sexuality Television Awkwardness Gender Blackness Erotic Media Cultural Studies Insecure, Awkward, and #Winning Intersectionality of Race, Gender, and Sexuality in the Works of Issa Rae Joanna L. Jenkins Andre Nicholson LaRonda Sanders-Senu Adria Y. Goldaman

- Published

- New York, Berlin, Bruxelles, Lausanne, Oxford, 2023. X, 294 pp.

- Product Safety

- Peter Lang Group AG